Geology of Australia

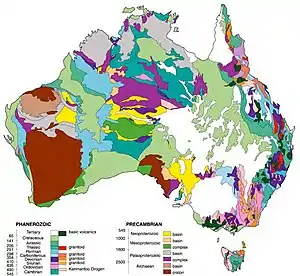

The geology of Australia includes virtually all known rock types, spanning a geological time period of over 3.8 billion years, including some of the oldest rocks on earth. Australia is a continent situated on the Indo-Australian Plate.

Components

Australia's geology can be divided into several main sections: the Archaean cratonic shields, Proterozoic fold belts and sedimentary basins, Phanerozoic sedimentary basins, and Phanerozoic metamorphic and igneous rocks.

Australia as a separate continent began to form after the breakup of Gondwana in the Permian, with the separation of the continental landmass from the African continent and Indian subcontinent. Australia rifted from Antarctica in the Cretaceous.

The current Australian continental mass is composed of a thick subcontinental lithosphere, over 200 kilometres (120 mi) thick in the western two-thirds and 100 kilometres (62 mi) thick in the younger eastern third. The Australian continental crust, excluding the thinned margins, has an average thickness of 38 kilometres (24 mi), with a range in thickness from 24 to 59 kilometres (15 to 37 mi).[1]

The continental crust is composed primarily of Archaean, Proterozoic and some Palaeozoic granites and gneisses. A thin veneer of mainly Phanerozoic sedimentary basins cover much of the Australian landmass (these are up to 7 kilometres or 4.3 miles thick).

These in turn are currently undergoing erosion by a combination of aeolian and fluvial processes, forming extensive sand dune systems, deep and prolonged development of laterite and saprolite profiles, and development of playa lakes, salt lakes and ephemeral drainage.

Blocks

The main continental blocks of the Australian continent are;

- The Yilgarn Craton, of Archaean age

- The Pilbara Craton of Archaean to Proterozoic age

- The Gawler Craton and Willyama Block, of Archaean to Proterozoic age.

These are in turn flanked by several Proterozoic orogenic belts and sedimentary basins, notably the

- Musgrave Block of granulite gneiss and igneous rocks

- The Arunta Block of amphibolite grade metamorphic rocks and granites

- The Gascoyne Complex, Glengarry Basin, and Bangemall Basin sandwiched between the Yilgarn and Arunta Blocks

Geologic history

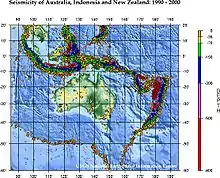

The geologic history of the Australian continental mass is extremely prolonged and involved, continuing from the Archaean to the recent. In a gross pattern, continental Australia grew from west to east, with Archean rocks mostly in the west, Proterozoic rocks in the centre, and Phanerozoic rocks in the east. Recent geologic events are confined to intraplate earthquakes, as the continent of Australia sits distant from the plate boundary.

The Australian continent evolved in five broad but distinct time periods, namely: 3800–2100 Ma, 2100–1300 Ma, 1300–600 Ma, 600–160 Ma and 160 Ma to the present. The first period saw the growth of nuclei about which cratonic elements grew, whereas the latter four periods involved the amalgamation and dispersal of Nuna, Rodinia and Pangea, respectively.

Tectonic setting

The Australian landmass has been part of all major supercontinents, but its association with Gondwana is especially notable as important correlations have been made geologically with the African continental mass and Antarctica.

Australia separated from Antarctica over a prolonged period beginning in the Permian and continuing through to the Cretaceous (84 Ma).

Continental Australia is unique among the continents in that the measured stress field is not parallel to the present-day north-northeast directed plate motion. Most of the stress state in continental Australia is controlled by compression originating from the three main collision boundaries located in New Zealand, Indonesia and New Guinea, and the Himalaya (transmitted through the Indian and Capricorn plates). South of latitude −30°, the stress trajectories are oriented east–west to northwest–southeast. North of this latitude, the stress trajectories are closer to the present day plate motion, being oriented east-northeast–west-southwest to northeast–southwest. Notably, the main stress trajectories diverge most markedly from one another in north–central New South Wales (east-southeast to north-northeast), although the area is not known historically for earthquake activity. Young mountain building (< 5 Ma) in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia is driven from plate convergence at the boundary in New Zealand.

Australia is currently moving toward Eurasia at the rate of 6–7 centimetres a year.

Archaean

There are three main cratonic shields of recognised Archaean age within the Australian landmass: The Yilgarn, the Pilbara and the Gawler cratons. Several other Archaean-Proterozoic orogenic belts exist, usually sandwiched around the edges of these major cratonic shields.

The history of the Archaean cratons is extremely complex and protracted. The cratons appear to have been assembled to form the greater Australian landmass in the late Archaean to mesoProterozoic, (~2400 Ma to 1,600 Ma).

Chiefly the Capricorn Orogeny is partly responsible for the assembly of the West Australian landmass by joining the Yilgarn and Pilbara cratons. The Capricorn Orogeny is exposed in the rocks of the Bangemall Basin, Gascoyne Complex granite-gneisses and the Glengarry, Yerrida and Padbury basins. Unknown Proterozoic orogenic belts, possibly similar to the Albany Complex in southern Western Australia and the Musgrave Block, represent the Proterozoic link between the Yilgarn and Gawler cratons, covered by the Proterozoic-Palaeozoic Officer and Amadeus basins.

See also:

Palaeoproterozoic

Western Australian Events

The assembly of the Archaean Yilgarn and Pilbara cratons of Australia was initiated at ~2200 Ma during the first phases of the Capricorn orogen.

The last stages of the 2770–2300 Ma Hamersley Basin on the southern margin of the Pilbara Craton are Palaeoproterozoic and record the last stable submarine-fluviatile environments between the two cratons prior to the rifting, contraction and assembly of the intracratonic ~1800 Ma Ashburton and Blair basins, the 1600–1070 Ma Edmund and Collier basins, the 1840–1620 Ma northern Gascoyne Complex, the 2000–1780 Ma Glenburgh Terrane in the southern Gascoyne Complex and the Errabiddy Shear Zone at the northwestern margin of the Yilgarn Craton.

Between approximately 2000–1800 Ma, on the northern margin of the Yilgarn Craton, the c. 1890 Ma Narracoota Volcanics of the Bryah Basin formed in a transverse back-arc rift sag basin during collision. Culmination of the cratonic collision resulted in the foreland sedimentary Padbury Basin. To the east the Yerrida and Eerarheedy Basins were passive margins along the Yilgarn's northern margin.

The c. 1830 Ma phase of the Capricorn Orogeny in this section of the Pilbara-Yilgarn boundary resulted in deformation of the Bryah-Padbury Basin and the western fringe of the Yerrida Basin, along with flood basalts. The Yapungku Orogeny (~1790 Ma) formed the Stanley Fold Belt on the northern margin of the Eerarheedy Basin, via assembly of the Archaean-Proterozoic fold belts of Northern Australia.

East Australian Events

The Palaeoproterozoic in southeastern Australia is represented by the polydeformed high-grade gneiss terranes of the Willyama Supergroup, Olary Block and Broken Hill Block, in South Australia and New South Wales. The Palaeoproterozoic in the north of Australia is represented mostly by the Mount Isa Block and complex fold-thrust belts.

These rocks, aside from suffering intense deformation, record a period of widespread platform cover sedimentation, ensialic rift-sag sedimentation including widespread dolomite platform cover, and extensive phosphorite deposition in the deeper sea beds.

Mesoproterozoic

The oldest rocks in Tasmania formed in the Mesoproterozoic on King Island and in the Tyennan Block.

Late Mesoproterozoic igneous events include:

- the Giles Complex mafic-ultramafic intrusions in the Musgrave Block at ~1080 Ma

- widespread sills in the Bangemall Basin and the Glenayle area at ~1080 Ma

- The Warukurna Large Igneous Province of ~1080 Ma

Neoproterozoic

Widespread deposition occurred in the Centralian Superbasin and Adelaide Geosyncline (Adelaide Rift Complex) during the Neoproterozoic. The Petermann Orogeny caused extensive uplift, mountain building and basin fragmentation in central Australia at the close of the Neoproterozoic.

Paleozoic

Cambrian

The Stavely Zone in Victoria is a boninite to MORB basalt terrane considered to have been connected with the boninites the Mount Read Volcanics of Northern Tasmania. In New South Wales, extensive deepwater sedimentation formed the Adaminaby Beds in Victoria and New South Wales. The Lachlan Fold Belt ophiolite sequences are considered to be of Cambrian age, and are obducted during the Lachlan Orogen.

The Petermann Orogeny in Central Australia, which started at the end of the Neoproterozoic, continued into the Cambrian, shedding a thick intracontinental sequence of fluvial sediments into the central Australian landmass. Marginal platforms and passive margin basins existed in South Australia – – formed in the foreland of the Delamerian Orogeny. Western Australian passive margin basins and platform cover begin at this stage. The extensive Antrim Plateau flood basalts, covering in excess of 12,000 square kilometres, erupt in the Cambrian of Western Australia, providing a useful chronostratigraphic marker.

- Stansbury basin

- Gascoyne Sub-basin – begins Cambrian, through to Tertiary

- Bonaparte Gulf Basin

Ordovician

Ordovician geological events in Australia involved Alpinotype orogeny in the Lachlan Fold Belt, resulting in the great serpentinite belts of western New South Wales, and accretion of deepwater molasse and flysch exemplified by the slate belts of Victoria and eastern New South Wales.

Victoria – 490–440 Ma

The late Cambrian to early Ordovician saw deepwater sedimentation of the St Arnaud and Castlemaine Group turbidites, which are now emplaced in the Stawell and Bendigo Zones. The middle Ordovician saw the deposition of the Sunbury Group in the Melbourne Zone, Bendoc Group and formation of the Molong Arc, a calc-alkaline volcanic arc which is related to the Kiandra Group turbidites.

Ordovician orogenies include the Lachlan Orogeny.

Silurian

During the Silurian Period most of the Australian continent in the west and centre was dry land. However, from Geraldton north to Exmouth Gulf along the far Western Australian coast a fluvial sediment basin existed. Near Kalbarri on the Murchison River the footprints of a giant water scorpion were found on land, the first animal to walk on the Australian continent. A gulf linked to the sea existed under what is now the Great Sandy Desert. Meanwhile, in the east there were volcanic arcs in New England, also west of Townsville and Cairns, and in NSW and Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory. Deep water sediments formed in the Cowra, Tumut and Hillend Troughs. The Yass Molong rise was a row of volcanoes. Granite intrusions formed in New South Wales and Victoria from 435 to 425 Mya, with the Bega batholith as young as 400 Mya. In NSW granites the distinction between I-type and S-type granites was discovered.[2]

Devonian

During the Devonian Period conditions were warm in Australia. There was a large bay in the Great Sandy Desert with reefs. The Calliope Arc went from the north of Rockhampton south to Grafton. Most of the centre and west of Australia was land mass. There were volcanic mountains off the current east coast supplying sediment into a basin on parts of the east. The basin contained limestone and river deposited sand. Andesite and Rhyolite volcanoes were found in central NSW, the Snowy Mountains, Eden, New England and near Clermont, Queensland. Baragwanathia longifolia was the first Australian land plant appearing at this time.

The Tabberabberan Orogeny compressed the eastern seaboard in an east–west direction, with Tasmania, Victoria and southern New South Wales folded 385 – 380 Mya. Northern NSW and Queensland was compressed 377 to 352 Mya. A major river drained the continental interior and passed eastwards at Parkes. The Bungle Bungle Range sandstone was formed in Western Australia from river sands. More Granite was intruded in the Devonian.

The Connors Arc and Baldwin arc formed behind Mackay and Western New England.[2]

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous Period saw the Eastern Highlands of Australia form as a result of its collision with what are now parts of South America (e.g. the Sierra de Cordoba) and New Zealand.

At the time they were formed they are believed to have been as high as any mountains on the planet today, but they have been almost completely eroded in the 280 million years since.

Another notable feature of Carboniferous Australia was a major ice age which left over half of the continent glaciated. Evidence for the cold conditions can be seen not only in glacial features dating from this period but also in fossil Gelisols from as far north as the Hunter River basin.

Mesozoic

Permo-Triassic

The Permian to Triassic in Australia is dominated by subduction zones on the eastern margin of the landmass, part of the Hunter-Bowen Orogeny. This was a major arc-accretion, subduction and back-arc sedimentary basin forming event which persisted episodically from approximately late Carboniferous in its initial stages, through the Permian and terminated in the Middle Triassic at around 229Ma to 225Ma.

In Western and Central Australia the then-extensive central Australian mountain ranges such as the Petermann Ranges were eroded by the Permian glacial event, resulting in thick marine to fluvial glacial tillite and fossiliferous limestone deposits and extensive platform cover. Rifting of Australia from India and Africa began in the Permian, resulting in the production of a rift basin and half-grabens of the basal portions of the long-lived Perth Basin. Petroleum was formed in the Swan Coastal Plain and Pilbara during this rifting, presumably in a rift valley lake where the bottom was deoxygenated (akin to Africa's Lake Tanganyika today)

See also:

- Perth Basin

- Bowen Basin

- Gunnedah basin

- Sydney basin and Geography of Sydney

- Ipswich basin/Clarence Moreton Basin

Jurassic

In the west of Australia the Jurassic was a tropical savannah to jungle environment, shown by advanced tropical weathering preserved in the regolith of the Yilgarn craton which is still preserved today.

Australia began rifting away from Antarctica in the Jurassic, which formed the Gippsland, Bass and Otway Basins in Victoria and the offshore shelf basins of South Australia and Western Australia, all of which host significant oil and gas deposits. The Prospect dolerite intrusion in the Sydney Basin was a result of tense continental crust breaking all the way down to the upper mantle during development of the rift divergence zone that occurred before the breakup of the Australian and Antarctic continents in the Eocene epoch.[3]

Jurassic coal-bearing basins were formed in north central Queensland, with significant marine platform cover extending across most of central Australia. Continued passive-margin subsidence and marine transgressions in the Perth Basin of Western Australia continued, with the Jurassic Cattamarra Coal Measures a notable fluvial terrigenous formation of the Jurassic.

See also

Cretaceous

The initial rifting of Australia and Antarctica in the Jurassic continued through the Cretaceous, with offshore development of a mid ocean ridge seafloor spreading centre. Tasmania was rifted off during this stage.

Cretaceous volcanism in the offshore of Queensland was related to a minor episode of arc formation, typified by the Whitsunday Islands, followed by development of offshore coral platforms, passive margin basins and far-field volcanism throughout the quiet Hunter-Bowen orogenic belt.

Cretaceous sedimentation continued in the Surat Basin. Some small Cretaceous volcanism was present at the edges of basement highs in the Great Artesian Basin, resulting in some sparse volcanic plugs today.

Cretaceous sedimentation continued in the Perth Basin.

Palaeocene to Recent

Tertiary

The Tertiary saw the majority of Australian tectonism cease. Sparse examples of intraplate volcanism exist, for instance the Glasshouse Mountains in Queensland, which are Tertiary examples of a chain of small volcanic plugs which decrease in age to the south, where they result in ~10,000-year-old maar volcanoes and basalts of the Newer Volcanics in South Australia and Victoria.

See also

See also – by state and territory

- Geology of the Australian Capital Territory

- Geology of New South Wales

- Geology of Tasmania

- Geology of South Australia

- Geology of Victoria

- Geology of Queensland

- Category:Geology of Western Australia

See also – by feature

See also – by industry

Notes

- Blewett, Richard S.; Kennett, Brian L. N.; Huston, David L. (2012). "Australia in Time and Space" (PDF). In Blewett, Richard S. (ed.). Shaping a Nation: A Geology of Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) and ANU E Press. doi:10.22459/SN.08.2012. ISBN 978-1-921862-82-3. OCLC 955187823. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- David Johnson: Geology of Australia Cambridge University Press, 2004

- Jones, I., Verdel, C., Crossingham, T., and Vasconcelos, P. (2017). Animated reconstructions of the Late Cretaceous to Cenozoic northward migration of Australia, and implications for the generation of east Australian mafic magmatism. Geosphere, 13(2), 460-481.

References

- Pirajno, F., Occhipinti, S. A. and Swager, C. P., 1998. Geology and tectonic evolution of the Palaeoproterozoic Bryah, Padbury and Yerrida basins, Western Australia: implications for the history of the south-central Capricorn orogen. Precambrian Research, 90: 119–140.

AUSTRALIA’S PLATE SETTING

- Braun J Dooley J Goleby B van der Hilst R. & Klootwijk C (Eds). 1998. Structure and Evolution of the Australian Plate. American Geophysical Union, Geodynamics Series 26:

- DeMetts et al. 2010. Geologically current plate motions. Geophysical Journal International 181: 1–80.

- Graham I. (Ed), 2008. A Continent on the Move: New Zealand Geoscience into the 21st Century. 388 p.

- Quigley MC. et al. 2010. Late Cenozoic tectonic geomorphology of Australia. Geological Society of London Special Publication 346: 243–265.

- Royer J-Y & Gordon RG. 1997. The motion and boundary between the Capricorn and Australian Plates. Science 277: 1268–1274.

- Tregoning P. 2003. Is the Australian Plate deforming? A space geodetic perspective. Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 22: 41–48.

GEOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK OF AUSTRALIA

- Johnson DP. 2009. The Geology of Australia. Second edition. Cambridge University Press. 360p

- Geoscience Australia. 2001. Palaeogeographic atlas of Australia. https://web.archive.org/web/20110602133645/http://www.ga.gov.au/meta/ANZCW0703003727.html

- Shaw RD et al. 1995. Australian crustal elements (1:5,000,000 scale map) based on the distribution of geophysical domains (v 1.0), Australian Geological Survey Organisation, Canberra.

MAPPING AUSTRALIA

- Aitken ARA. 2010. Moho geometry gravity inversion experiment (MoGGIE): A refined model of the Australian Moho, and its tectonic and isostatic implications. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 297: 71–83.

- Birch WD. 2003. Geology of Victoria. Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 23.

- Burrett CF & Martin EL. 1989. Geology and mineral resources of Tasmania. Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 15.

- Day RW et al. 1983. Queensland geology: a companion volume to the 1:2,500,000 scale geological map (1975). Geological Survey of Queensland Publication 383.

- Drexel JF et al. 1993–1995. The geology of South Australia. Geological Survey of South Australia, Bulletin 54 (2 v.)

- Earth Science History Group. 2010. Thematic Issue: Snapshots of the geological program covering the whole of Australia. Geological Society of Australia ESHG Newsletter 41: 43 p.

- Finlayson DM. 2008. A geological guide to Canberra Region and Namadgi National Park. Geological Society of Australia (ACT Division), 139 p.

- Geological Survey of Western Australia, 1990. Geology and Mineral Resources of Western Australia. Memoir 3.

- McKenzie et al. (ed) 2004. Australian Soils and Landscapes: an illustrated compendium. CSIRO Publishing: 395 p.

- National Library of Australia. 2007. Australia in Maps: great maps in Australia's history from the National Library's collection: 148 p.

- Scheibner E. 1996–1998. Geology of New South Wales – synthesis. Geological Survey of New South Wales Memoir geology: 13 (2 v.)

AUSTRALIAN LITHOSPHERE

- Clitheroe G. et al. 2000. The crustal thickness of Australia, Journal Geophysical Research 105: 13,697–13,713.

- Hillis RR & Muller RD. (eds) 2003. Evolution and dynamics of the Australian Plate. Geological Society of Australia Special Publication 22: 432 p.

AUSTRALIA THROUGH TIME: TECTONIC EVOLUTION

- Betts PG & Giles D. 2006. The 1800–1100 Ma tectonic evolution of Australia. Precambrian Research 144: 92–125.

- Bishop P & Pillans B. (eds) 2010. Australian Landscapes. Geological Society of London Special Publication 346.

- Cawood PA. 2005. Terra Australis Orogen: Rodinia breakup and development of the Pacific and Iapetus margins of Gondwana during the Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic. Earth-Science Reviews 69: 249–279.

- Cawood PA & Korsch RJ. (eds) 2008. Assembling Australia: Proterozoic building of a continent. Precambrian Research 166: 1–396.

- Champion DC et al. 2009. Geodynamic synthesis of the Phanerozoic of eastern Australia and implications for metallogeny. Geoscience Australia Record 2009/18.

- Gray DR & Foster DA. 2004. Tectonic review of the Lachlan Orogen: historical review, data synthesis and modern perspectives. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 51: 773–817.

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. 2007. Great Barrier Reef Climate Change Action Plan 2007–2011. http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/corp_site/key_issues/climate_change/management_responses

- Hawkesworth CJ et al. 2010. The generation and evolution of the continental crust. Journal of the Geological Society 167: 229–248.

- Korsch RJ. et al. 2011. Australian island arcs through time: Geodynamic implications for the Archean and Proterozoic. Gondwana Research 19: 716–734.

- Moss PT & Kershaw AP. 2000. The last glacial cycle from the humid tropics of northeastern Australia: comparison of a terrestrial and a marine record. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 155: 155–176.

- Myers JS. et al. 1996. Tectonic evolution of Proterozoic Australia. Tectonics 15: 1431–1446.

- Neumann NL & Fraser GL. 2007. Geochronological synthesis and time-space plots for Proterozoic Australia. Geoscience Australia Record 2007/06: 216 p.

- van Ufford AQ & Cloos M. 2005. Cenozoic tectonics of New Guinea. AAPG Bulletin 89: 119–140.

- Veevers JJ. (ed) 2000. Billion-Year Earth History of Australia and Neighbours in Gondwanaland. GEMOC Press, Sydney: 388 p.

- Veevers JJ. 2006. Updated Gondwana (Permian–Cretaceous) earth history of Australia. Gondwana Research 9: 231–260

DEEP TIME

- Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2008. Thematic Issue – Geochronology of Australia. Volume 55(6/7).

- Laurie J. (ed) 2009. Geological Timewalk, Geoscience Australia, Canberra: 53 p.