Arts in Australia

The Arts in Australia refers to the visual arts, literature, performing arts and music in the area of, on the subject of, or by the people of the Commonwealth of Australia and its preceding Indigenous and colonial societies. Indigenous Australian art, music and story telling attaches to a 40–60,000-year heritage and continues to affect the broader arts and culture of Australia. During its early western history, Australia was a collection of British colonies, therefore, its literary, visual and theatrical traditions began with strong links to the broader traditions of English and Irish literature, British art and English and Celtic music. However, the works of Australian artists – including Indigenous as well as Anglo-Celtic and multicultural migrant Australians – has, since 1788, introduced the character of a new continent to the global arts scene – exploring such themes as Aboriginality, Australian landscape, migrant and national identity, distance from other Western nations and proximity to Asia, the complexities of urban living and the "beauty and the terror" of life in the Australian bush.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of Australia |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Australia portal |

Notable Australian writers have included the Nobel laureate Patrick White, the novelists Colleen McCullough and Henry Handel Richardson and the bush poets Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson. Leading Australian performing artists have included Robert Helpmann of the Australian Ballet, Joan Sutherland of Opera Australia and the humourist Barry Humphries. Prominent Australian musical artists have included the Australian country music singer Slim Dusty, rising star Cody Simpson, folk-rocker Paul Kelly, "pop princess" Kylie Minogue and rock n roll bands the Bee Gees, AC/DC, INXS and Powderfinger. Quintessentially Australian art styles include the Heidelberg School the Hermannsburg School and the Western Desert Art Movement.

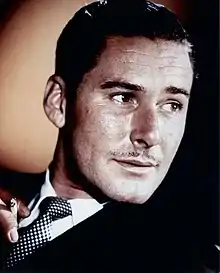

Australian cinema has a long tradition with a body of work producing popular classics such as Crocodile Dundee and The Man From Snowy River, and arthouse successes such as Picnic at Hanging Rock and Ten Canoes. Prominent Australian trained filmed artists include Errol Flynn, Mel Gibson, Nicole Kidman, Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett.

Notable institutions for the arts include the UNESCO listed Sydney Opera House, the National Gallery of Victoria, the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra and the National Institute of Dramatic Art in Sydney.

Overview

The arts in Australia, including the fields of cinema, music, visual arts, theatre, dance and crafts often reflect general trends in Western arts. However, the arts as practiced by indigenous Australians represent a unique Australian cultural tradition, and Australia's landscape and history have contributed to some unique variations in the styles inherited by Australia's various migrant communities.[1][2][3]

At the close of the 19th century, the painters of the Heidelberg School began to capture the unique colours of the Australian bush, famed writers Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson presented conflicting views of the harshness and romance of life in Australia, and performing artists like opera singer Dame Nellie Melba made a mark internationally in classical European culture. During the 20th century, writers and performers like C J Dennis, Barry Humphries and Paul Hogan both mocked and celebrated Australian cultural stereotypes, while shifting demographics saw a diversification of artistic output, with writers like feminist Germaine Greer challenging traditional cultural norms.

Australia's capital cities each support traditional "high culture" institutions in the form of major art galleries, ballet troupes, theaters, symphony orchestras, opera houses and dance companies. Leading Australian performers in these fields have included the opera Dames Nellie Melba and Joan Sutherland, dancers Edouard Borovansky and Sir Robert Helpmann, and choreographer/dancers such as Graeme Murphy and Meryl Tankard. Opera Australia is based in Sydney at the world-renowned Sydney Opera House.[4] The Australian Ballet, Melbourne and Sydney symphony orchestras are also well regarded cultural institutions.

Organisations such as the Sydney Theatre Company and National Institute of Dramatic Art have fostered students of theatre, film, and television several of whom have continued to international success, with actors like Cate Blanchett and Geoffrey Rush having been associated with both institutions.

Independent culture thrives in all capital cities and exists in most large regional towns. The independent arts of music, film, art and street art are the most extensive. Melbourne's independent music scene, is one of the largest in the world, whilst another can be found in the multitude of international street artists visiting Melbourne and, to a lesser extent, other major cities, to work for a period of time. As of February 2015, Arts and recreation services was the strongest industry in Australia by total number of employed persons growing by 20.59% since the same time in 2013.[5]

Visual arts

Painting, drawing and sculpture

The visual arts have a long history in Australia, dating back around 30,000 years, and examples of ancient Aboriginal rock art can be found throughout the continent, notably in national parks such as the UNESCO-listed sites at Uluru and Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory, and also within protected parks in urban areas such as Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park in Sydney.[6] In the mid-twentieth century, the landscape paintings of Albert Namatjira were popular and received national and international acclaim.[7] Since the 1970s, contemporary Indigenous Australian artists have used acrylic paints in styles such as that of the Western Desert Art Movement, which leading critic Robert Hughes saw as "the last great art movement of the 20th century".[8] Art is important both culturally and economically to Indigenous society; art critic Sasha Grishin concluded that central Australian Indigenous communities have "the highest per capita concentrations of artists anywhere in the world".[9] Contemporary artists whose work has been exhibited internationally such as at the Venice Biennale, include Rover Thomas and Emily Kngwarreye, while designs were commissioned from several nationally recognised artists in 2006 for the new Musée du quai Branly buildings. The artists included Paddy Bedford, John Mawurndjul, Ningura Napurrula, Lena Nyadbi, Michael Riley, Judy Watson, Tommy Watson and Gulumbu Yunupingu.[10][11]

Following the arrival of permanent European settlement in Australia in 1788, the story of early Australian painting has been described as requiring of artists a shift from a "European sense of light" to an "Australian sense of light". The origins of distinctly Australian painting is often associated with the Heidelberg School of the 1880s–1890s. Artists such as Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin and Tom Roberts applied themselves to recreating in their art a truer sense of light and colour as seen in the Australian landscape. Like the European Impressionists, they painted in the open air. These artists found inspiration in the unique light and colour which characterises the Australian bush.

Among the first Australian artists to gain a reputation overseas was the impressionist John Russell during the 1880s. Another notable expatriate artist of the era was Rupert Bunny, a painter of landscape, allegory and sensual and intimate portraits. Ernst William Christmas also made a name internationally.

Among the principal Australian artists of the 20th century are the surrealists Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd and Russell Drysdale, the avant-garde Brett Whiteley, the painter/sculptors William Dobell and Norman Lindsay, the landscapists Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Albert Namatjira and Lloyd Rees, and modernist photographer Max Dupain. Each has helped to define the unique character of the visual arts in Australia.[1]

Modernism arrived in Australia early in the 20th century. Among the earliest exponents were Grace Cossington Smith and Margaret Preston. Humorist Barry Humphries has been a provocative exponent of dadaism in Australia.[12]

Popular with the general community have been Ken Done, best known for his design work, Pro Hart and Rolf Harris, a British/Australian living in the UK who is popular as a musician, composer, painter and television host. Ricky Swallow, Patricia Piccinini, Susan Norrie, Callum Morton, Rover Thomas and Emily Kame Kngwarreye have all represented Australians at the Venice Biennale using the traditional mediums of sculpture, photography and painting while instilling them with a renewed vigour. A new generation of Aboriginal artists, while not rejecting the culture of the past, endeavour to move the artistic dialog forward, including Gordon Bennett, Rosella Namok, Richard Bell and Julie Dowling.

In recent years the art market has been democratised and art is judged on its merits rather than snobbery. A cohort of male artists aged under fifty (Dane Lovett, Adam Cullen, Ben Quilty, Anthony Bennett, Simon Cuthbert, Rhys Lee, Ben Frost and Alasdair McIntyre) have an expressive style and use humour in their work.

In addition street art is also a prominent feature in major cities such as Melbourne and Sydney. Though there is some debate over the legality, some councils have expressed greater recognition of the urban art movement.

Australia has a number of notable museums and galleries, including the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, the National Gallery of Australia, National Portrait Gallery of Australia and National Museum of Australia in Canberra, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney.

Aboriginal Rock Art, Ubirr Art Site, Kakadu National Park

Aboriginal Rock Art, Ubirr Art Site, Kakadu National Park

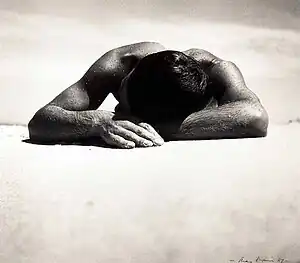

Sunbaker (1937) an iconic photograph by Max Dupain

Sunbaker (1937) an iconic photograph by Max Dupain

Cinema, TV and video games

Australia has a long history of film production. Australia's first dedicated film studio, the Limelight Department, was created by The Salvation Army in Melbourne in 1898, and is believed to have been the world's first.[13] The world's first feature-length film was the Australian production The Story of the Kelly Gang of 1906.[14] After such early successes, Australian cinema suffered from the rise of Hollywood.

In 1933, In the Wake of the Bounty was directed by Charles Chauvel, who cast Tasmanian-born Errol Flynn as the leading actor.[15] Flynn went on to a celebrated career in Hollywood. Chauvel directed a number of successful Australian films, the last being 1955's Jedda, which was notable for being the first Australian film to be shot in colour, and the first to feature Aboriginal actors in lead roles and to be entered at the Cannes Film Festival.[16] It was not until 2006 and Rolf de Heer's Ten Canoes that a major feature-length drama was shot in an indigenous language.

The first Australian Oscar was won by 1942's Kokoda Front Line!, directed by Ken G. Hall.[17]

Television broadcasting began in Australia in 1956. The majority of locally produced content was broadcast live-to-air, with very little local programming from these first few years of Australian TV broadcasting recorded. Notable early arts programs were Bandstand, hosted by Brian Henderson; Six O'Clock Rock, hosted by Johnny O'Keefe and the first Australian serial drama, Autumn Affair. A TV series The Adventures of Long John Silver was made in Sydney for the American and British market; it was shown on the ABC in 1958.

During the late 1960s and 1970s an influx of government funding saw the development of a new generation of filmmakers telling distinctively Australian stories, including directors Peter Weir, George Miller and Bruce Beresford. Films such as Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and Sunday Too Far Away (1975) had an immediate international impact. The 1980s is often regarded as a golden age of Australian cinema, with many successful films, from the historical drama of Gallipoli (1981) to the dark science fiction of the Mad Max sequels (1981–85), the romantic adventure of The Man From Snowy River (1982) or the comedy of Crocodile Dundee (1986).[18]

In 1982, the first Australian game development studios to achieve global success, Melbourne House (now Krome Studios Melbourne) publisherd a text adventure adaption of The Hobbit for the ZX Spectrum. Other early game development studios in Australia include Strategic Studies Group, who developed Reach for the Stars in 1983, and Micro Forté, founded in 1985.

A major theme of Australian cinema has been survival in the harsh Australian landscape. A number of thrillers and horror films dubbed "outback gothic" have been created, including Wake in Fright, Walkabout (1971), The Cars That Ate Paris (1974) and Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Razorback (1984) and Shame (1988) in the 1980s, and Japanese Story (2003), The Proposition (2005) and the world-renowned Wolf Creek (2006) in the 21st century. These films depict the Australian outback and its wilderness and creatures as deadly, and its people as outcasts and psychopaths disconnected to modern urban Australia. These are combined with futuristic post-apocalyptic themes in the Mad Max series.

The 1990s saw a run of successful comedies such as Strictly Ballroom (1992), Muriel's Wedding (1994) and The Castle (1996), which helped launch the careers of Toni Collette, P. J. Hogan, Eric Bana and Baz Luhrmann. This group was joined in Hollywood by actors including Russell Crowe, Cate Blanchett and Heath Ledger who also rose to international prominence.

The domestic film industry continues to produce a reasonable number of films each year. The industry is also supported by US producers who produce in Australia following the decision by Fox head Rupert Murdoch to utilise new studios in Melbourne and Sydney where filming could be completed well below US costs. Notable productions include The Matrix, Star Wars episodes II and III, and Australia starring Nicole Kidman and Hugh Jackman.

The Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne is Australia's national museum of film, video games, digital culture and art. During the 2015–16 financial year, 1.45 million people visited ACMI, making it the most visited moving image museum in the world.

Literature

Australian writers who have obtained international renown include the Nobel winning author Patrick White, as well as authors Peter Carey, Thomas Keneally, Colleen McCullough, Nevil Shute and Morris West. Notable contemporary expatriate authors include the feminist Germaine Greer, art historian Robert Hughes and humorists Barry Humphries and Clive James.[19]

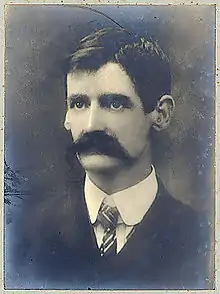

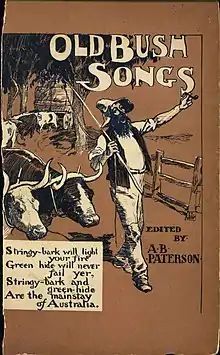

Among the important authors of classic Australian works are the poets Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, C J Dennis and Dorothea McKellar. Dennis wrote in the Australian vernacular, while McKellar wrote the iconic patriotic poem My Country. At one point, Lawson and Paterson contributed a series of verses to The Bulletin magazine in which they engaged in a literary debate about the nature of life in Australia. Lawson said Paterson was a romantic and Paterson said Lawson was full of doom and gloom.[20] Lawson is widely regarded as one of Australia's greatest writers of short stories, while Paterson's poems The Man From Snowy River and Clancy of the Overflow remain amongst the most popular Australian bush poems. Significant political poets of the 20th century included Dame Mary Gilmore and Judith Wright. Among the best known contemporary poets are Les Murray and Bruce Dawe.

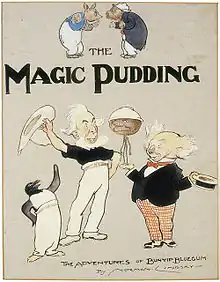

Novelists of classic Australian works include Marcus Clarke (For the Term of His Natural Life), Henry Handel Richardson (The Fortunes of Richard Mahony), Joseph Furphy (Such Is Life), Miles Franklin (My Brilliant Career) and Ruth Park (The Harp in the South). In terms of children's literature, Norman Lindsay (The Magic Pudding) and May Gibbs (Snugglepot and Cuddlepie) are among the Australian classics, while eminent Australian playwrights have included Steele Rudd, David Williamson, Alan Seymour and Nick Enright.

Although historically only a small proportion of Australia's population have lived outside the major cities, many of Australia's most distinctive stories and legends originate in the outback, in the drovers and squatters and people of the barren, dusty plains.[21]

Contemporary works dealing with the migrant experience include Melina Marchetta's Looking for Alibrandi and Anh Do's memoir The Happiest Refugee, which won the Indie Book of the Year Award for 2011 and tells the story of his experience as a Vietnamese refugee travelling to and growing up in Australia.[22]

David Unaipon is known as the first indigenous author. Oodgeroo Noonuccal was the first Aboriginal Australian to publish a book of verse.[23] A significant contemporary account of the experiences of Indigenous Australia can be found in Sally Morgan's My Place.

Charles Bean (The Story of Anzac: From the Outbreak of War to the End of the First Phase of the Gallipoli Campaign 4 May 1915, 1921) Geoffrey Blainey (The Tyranny of Distance, 1966), Robert Hughes (The Fatal Shore, 1987), Manning Clark (A History of Australia, 1962–87), and Marcia Langton (First Australians, 2008) are authors of important Australian histories.

Performing arts

Dance

Indigenous dance

Traditional Aboriginal Australian dance is closely associated with song and designed to make present the reality of the Dreamtime. In some instances, the dances imitate the actions of a particular animal in the process of telling a story. Traditional ritual performances define roles, responsibilities and country, giving an understanding of people's relationship with social, geographical and environmental forces. Performances may be associated with specific sacred places. Body decoration and specific gestures related to kin and other relationships (such as to Dreamtime beings with which individuals and groups). For a number of Aboriginal Australian groups, their dances are secret and or sacred, gender could also be an important factor in some ceremonies with men and women having separate ceremonial traditions.[24]

A corroboree, a generic word for a meeting of Australian Aboriginal peoples often including dance as well as elements of sacred ceremony and/or celebration, has been incorporated into the English language and used to explain a practice that is different from ceremony and more widely inclusive than theatre or opera.[25]

In the latter part of the 20th century the influence of Indigenous Australian dance traditions has been seen with the development of concert dance, particularly in contemporary dance with the National Aboriginal Islander Skills Development Association providing training to Indigenous Australians in dance, and the Bangarra Dance Theatre.

Ballet

The Australian Ballet is the foremost classical ballet company in Australia. It was founded by the English ballerina Dame Peggy van Praagh in 1962 and is today recognised as one of the world's major international ballet companies. It is based in Melbourne and performs works from the classical repertoire as well as contemporary works by major Australian and international choreographers. As of 2010, it was presenting approximately 200 performances in cities and regional areas around Australia each year as well as international tours. Regular venues include: the Arts Centre Melbourne, Sydney Opera House, Sydney Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre and Queensland Performing Arts Centre.[26][27] Robert Helpmann is among Australia's best known ballet dancers.

Other forms of dance

Bush dance has developed in Australia as a form of traditional dance, drawing from English, Irish, Scottish and other European dance. Favourite dances in the community include such as the Irish Céilidh "Pride of Erin" and the quadrille "The Lancers". Locally originated dances include the "Waves of Bondi", the Melbourne Shuffle and New Vogue.

Many immigrant communities continue their own dance traditions on a professional or amateur basis. Traditional dances from a large number of ethnic backgrounds are danced in Australia, helped by the presence of enthusiastic immigrants and their Australian-born families. It is quite common to see dances from the Baltic region, as well as Scottish, Irish, Indian, Indonesian or African dance being taught at community centres and dance schools in Australia.

Baz Luhrmann's popular 1992 film Strictly Ballroom, starring Paul Mercurio contributed to an increased interest in dance competition in Australia, and a number of popular dance shows including So You Think You Can Dance have featured on television in recent years.

Indigenous music

Aboriginal song is an integral part of Aboriginal culture. The most famous feature of their music is the didgeridoo. This wooden instrument, used amongst the Aboriginal tribes of northern Australia, makes a distinctive droning sound and its use has been adopted by a wide variety of non-Aboriginal performers.

Aboriginal musicians have turned their hand to Western popular musical forms, often to considerable commercial success. Pioneers included Lionel Rose, and Jimmy Little, while notable contemporary examples include Archie Roach, the Warumpi Band, NoKTuRNL and Yothu Yindi. Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu (formerly of Yothu Yindi) has attained international success singing contemporary music in English and in the language of the Yolngu. Christine Anu is a successful Torres Strait Islander singer.

Australian country music has been popular among indigenous communities, with performers including Troy Cassar-Daley rising to national prominence.

Amongst young Australian aborigines, African-American and Aboriginal hip hop music and clothing is popular.[28] Aboriginal boxing champion and former professional rugby league footballer Anthony Mundine identified US rapper Tupac Shakur as a personal inspiration, after Mundine's release of his 2007 single, Platinum Ryder.[29]

The Deadlys are an annual celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander achievement in music, sport, entertainment and community.

Folk music and national songs

The early Anglo-Celtic immigrants of the 18th and 19th centuries introduced folk ballad traditions which were adapted to Australian themes: "Bound for Botany Bay" tells of the voyage of British convicts to Sydney, "The Wild Colonial Boy" evokes the spirit of the bushrangers, and "Click Go the Shears" speaks of the life of Australian shearers. The lyrics of Australia's best-known folk song, "Waltzing Matilda", were written by the bush poet Banjo Paterson in 1895.[30] Adopted by Australian soldiers during World War I, this song remains popular and is often sung at sporting events, including the closure of the Sydney Olympics in 2000, by Australian country music singer Slim Dusty.[31]

Other well-known singers of Australian folk music include Rolf Harris (who wrote "Tie Me Kangaroo Down Sport"), John Williamson, and Eric Bogle whose 1972 song "And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda" is a sorrowful lament to the Gallipoli Campaign. Bush dance is a traditional style of dance from Australia with strong Celtic roots, and influenced country music. It is generally accompanied by such instruments as the fiddle, accordion, concertina and percussion instruments.[32] A well-known Bush band is The Bushwackers.[33]

The national anthem of Australia is "Advance Australia Fair":

- Australians all let us rejoice,

- For we are one and free;

- We've golden soil and wealth for toil,

- Our home is girt by sea;

- Our land abounds in Nature's gifts

- Of beauty rich and rare;

- In history's page, let every stage

- Advance Australia fair!

- In joyful strains then let us sing,

- Advance Australia fair!

Unofficial pop music anthems of Australia include Peter Allen's "I Still Call Australia Home" and Men at Work's "Down Under".

Classical music

The earliest Western musical influences in Australia can be traced back to two distinct sources: the first free settlers who brought with them the European classical music tradition, and the large body of convicts and sailors, who brought the traditional folk music of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The practicalities of building a colony mean that there is very little music extant from this early period although there are samples of music originating from Hobart and Sydney that date back to the early 19th century.[34]

Nellie Melba (1861–1931) travelled to Europe in 1886 to commence her international career as an opera singer. She became among the best known Australians of the period and participated in early gramophone recording and radio broadcasting.[35]

The establishment of choral societies (c. 1850) and symphony orchestras (c. 1890) led to increased compositional activity, although many Australian classical composers attempted to work entirely within European models. A lot of works leading up to the first part of the 20th century were heavily influenced by the folk music of other countries (Percy Grainger's Country Gardens of 1918 being a good example of this) and a very conservative British orchestral tradition.[34]

In the war and post-war eras, as pressure built to assert a national identity in the face of the looming superpower of the United States and the "motherland" Britain, composers looked to their surroundings for inspiration. John Antill[36] and Peter Sculthorpe began to incorporate elements of Aboriginal music, and Richard Meale drew influence from south-east Asia (notably using the harmonic properties of the Balinese Gamelan, as had Percy Grainger in an earlier generation).[34]

By the beginning of the 1960s, Australian classical music erupted with influences, with composers incorporating disparate elements into their work, ranging from Aboriginal and south-east Asian music and instruments, to American jazz and blues, to the belated discovery of European atonality and the avant-garde. Composers like Don Banks, Don Kay, Malcolm Williamson and Colin Brumby epitomise this period.[34] In recent times composers including Liza Lim, Carl Vine, Georges Lentz, Matthew Hindson, Yitzhak Yedid, Nigel Westlake, Ross Edwards, Graeme Koehne, Elena Kats-Chernin, Richard Mills, Stuart Greenbaum and Brett Dean have embodied the pinnacle of established Australian composers.

Well-known Australian classical performers include: sopranos Dame Joan Sutherland, Dame Joan Hammond, Joan Carden, Yvonne Kenny, Sara Macliver and Emma Matthews; pianists Roger Woodward, Eileen Joyce, Michael Kieran Harvey, Geoffrey Tozer, Geoffrey Douglas Madge, Leslie Howard and Ian Munro; guitarists John Williams and Slava Grigoryan; horn player Barry Tuckwell; oboist Diana Doherty; violinists Richard Tognetti and Elizabeth Wallfisch; cellists John Addison and David Pereira; organist Christopher Wrench; orchestras like the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, the Australian Chamber Orchestra and the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra; and conductors Sir Bernard Heinze, Sir Charles Mackerras, Richard Bonynge, Simone Young and Geoffrey Simon. Indigenous performers like didgeridoo player William Barton and immigrant musicians like Egyptian-born oud virtuoso Joseph Tawadros have stimulated interest in their own music traditions and have also collaborated with other musicians and ensembles both in Australia and internationally.

Pop and rock

.jpg.webp)

Australia has produced a large variety of popular music from the internationally renowned work of the Bee Gees, AC/DC, INXS, Nick Cave, Cody Simpson or Kylie Minogue to the popular local content of John Farnham or Paul Kelly.[37]

Among the brightest stars of early Australian rock and roll was Johnny O'Keefe, who formed a band in 1956; his hit Wild One made him the first Australian rock'n'roller to reach the national charts.[38] While US and British content dominated airwaves and record sales into the 1960s, local successes began to emerge – notably The Easybeats and the folk-pop group The Seekers had significant local success and some international recognition, while the bands the Bee Gees and AC/DC had their first hits in Australia before going on to international success.

The arrival of the 1961 underground movement into the mainstream in the early 1970s changed Australian music permanently. Skyhooks were far from the first people to write songs in Australia by Australians about Australia, but they were the first ones to make good money doing it. The two best-selling Australian albums made up to that time put Australian music on the map. Within a few years, the novelty had worn off and it became commonplace to hear distinctively Australian lyrics and sounds side-by-side with imports.

During the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s Australian performers continued to do well on the local and international music scenes, for example Cold Chisel, INXS, Men at Work and Kylie Minogue, Natalie Imbruglia, Savage Garden and Silverchair. In the early 21st century, bands such as Jet, Wolfmother, Eskimo Joe, Grinspoon, The Vines, The Living End, Pendulum, Delta Goodrem and others were enjoying success internationally.

Domestically, John Farnham has remained one of Australia's best-known performers, with a career spanning over 40 years.[39] Singer-songwriter Paul Kelly whose music style straddles folk, rock, and country has been described as the poet laureate of Australian music.[40]

The national expansion of ABC youth radio station Triple J during the 1990s has increased the profile and availability of home-grown talent to listeners nationwide. Since the mid-1990s a string of successful alternative Australian acts have emerged; artists to achieve both underground (critical) and mainstream (commercial) success include You Am I, Grinspoon, Powderfinger and Jet.

Country music

Australia has a long tradition of country music, which has developed a style quite distinct from its US counterpart, influenced by Celtic folk ballads and the traditions of Australian bush balladeers like Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson. Pioneers of popular country music in Australia included Tex Morton in the 1930s and Smoky Dawson from the 1940s onward.

Slim Dusty (1927–2003) was known as the King of Australian Country Music. His successful career spanned almost six decades and his 1957 hit "A Pub With No Beer" was the biggest-selling record by an Australian to that time, the first Australian single to go gold, and the first and only 78 rpm record to be awarded a gold disc.[41] Dusty recorded and released his one-hundredth album in the year 2000 and was given the honour of singing Waltzing Matilda in the closing ceremony of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Dusty's wife Joy McKean penned several of his most popular songs.

Other popular performers of Australian country music include: John Williamson (who wrote the iconic song "True Blue"), Lee Kernaghan, Kasey Chambers and Sara Storer. In the United States, Australian country music stars including Olivia Newton-John and Keith Urban have attained great success.

Country music has also been a particularly popular form of musical expression among the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Troy Cassar-Daley is among Australia's successful indigenous performers.

The Tamworth Country Music Festival is an annual country music festival held in Tamworth, New South Wales. It celebrates the culture and heritage of Australian country music. During the festival the Country Music Association of Australia holds the Country Music Awards of Australia ceremony awarding the Golden Guitar trophies.

Theatre

The ceremonial dances of indigenous Australians which recount the stories of the Dreamtime, comprise theatrical aspects and have been performed since time immemorial during the 40–60,000-year Aboriginal occupation of Australia.[42] European traditions came to Australia with the First Fleet in 1788, with the first production being performed in 1789 by convicts.[43] Two centuries later, the extraordinary circumstances of the foundations of Australian theatre were recounted in Our Country's Good by Timberlake Wertenbaker: the participants were prisoners watched by sadistic guards and the leading lady was under threat of the death penalty.[43]

The Theatre Royal, Hobart, opened in 1837 and it remains the oldest theatre in Australia.[44] The Australian gold rushes beginning in the 1850s provided funds for the construction of grand theatres in the Victorian style. A theatre was built on the present site of Melbourne's Princess Theatre in 1854. The present building now hosts major international productions as well as live performance events such as the Melbourne International Comedy Festival.[45]

The Melbourne Athenaeum was built during this period and later became Australia's first cinema, screening The Story of the Kelly Gang, the world's first feature film in 1906. Mark Twain, Nellie Melba, Laurence Olivier and Barry Humphries have all performed on this historic stage.[46] The Queen's Theatre, Adelaide opened with Shakespeare in 1841 and is today the oldest theatre on the mainland.[47]

After Federation in 1901, theatre productions evidenced the new sense of national identity. On Our Selection (1912) by Steele Rudd, told of the adventures of a pioneer farming family and became immensely popular. Sydney's grand Capitol Theatre opened in 1928 and after restoration remains one of the nation's finest auditoriums.[48]

In 1955, Summer of the Seventeenth Doll by Ray Lawler portrayed resolutely Australian characters and went on to international acclaim. That same year, young Melbourne artist Barry Humphries performed as Edna Everage for the first time at Melbourne University's Union Theatre. Humphries left for London in his early 20s and enjoyed success on stage, including in Lionel Bart's musical, Oliver!. His satirical stage creations – notably Dame Edna and later Les Patterson –– became Australian cultural icons. Humphries also achieved success in the US with tours on Broadway and television appearances and has been honoured in Australia and Britain.[49]

The National Institute of Dramatic Art was created in Sydney in 1958. This institute has since produced a list of famous alumni including Cate Blanchett, Mel Gibson and Baz Luhrmann.[50]

Construction of the Adelaide Festival Centre began in 1970 and South Australia's Sir Robert Helpmann became director of the Adelaide Festival of Arts.[51][52] The new wave of Australian theatre debuted in the 1970s. The Belvoir St Theatre presented works by Nick Enright and David Williamson. In 1973, the Sydney Opera House, which had been based on a design by Jørn Utzon, was officially opened.[53] Opera Australia made its home in the building and its reputation was enhanced by the presence of the diva Joan Sutherland.

The Sydney Theatre Company was founded 1978 becoming one of Australia's foremost theatre companies.[54] The Bell Shakespeare Company was created in 1990. A period of success for Australian musical theatre came in the 1990s with the debut of musical biographies of Australian music singers Peter Allen (The Boy From Oz in 1998) and Johnny O'Keefe (Shout! The Legend of The Wild One).

In The One Day of the Year, Alan Seymour studied the paradoxical nature of the ANZAC Day commemoration by Australians of the defeat of the Battle of Gallipoli. Ngapartji Ngapartji, by Scott Rankin and Trevor Jamieson, recounts the story of the effects on the Pitjantjatjara people of nuclear testing in the Western Desert during the Cold War. It is an example of the contemporary fusion of traditions of drama in Australia with Pitjantjatjara actors being supported by a multicultural cast of Greek, Afghan, Japanese and New Zealand heritage.[55]

See also

References

- "Australian painters". Australian Culture and Recreation Portal. Australia Government. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- "Film in Australia - Australia's Culture Portal". Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "Australia in Brief: Culture and the arts - Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Opera in Australia - Australia's Culture Portal". Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Hutchison, Michelle (18 June 2015). "2015 Careers in Australia Report". Finder.com.au. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- Aboriginal Australia – Rock Art Archived 31 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Tourism Australia. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Kleinert, Sylvia (2000). Namatjira, Albert (Elea) (1902–1959). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- Henly, Susan Gough (6 November 2005). "Powerful growth of Aboriginal art", The New York Times. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Grishin, Sasha (8 December 2007). "Next generation Papunya". The Canberra Times. p. 6.

- Claire Armstrong, ed. (2006). Australian Indigenous Art Commission: Musee du quai Branly. Eleonora Triguboff, Art & Australia, and Australia Council for the Arts. ISBN 0-646-46045-5.

- Croft, Brenda, ed (2007). Culture Warriors: National Indigenous Art Triennial 2007. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia. ISBN 978-0-642-54133-8

- Robert Hughes; The Art of Australia; Penguin; Revised Edition 1970

- "Australia's first film studio". Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Video Overview The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906) on ASO – Australia's audio and visual heritage online". Aso.gov.au. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Video Overview In the Wake of the Bounty (1933) on ASO – Australia's audio and visual heritage online". Aso.gov.au. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "JEDDA". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Video Overview Kokoda Front Line! (1942) on ASO – Australia's audio and visual heritage online". Aso.gov.au. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "film". Murdoch.edu.au. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Australian language, letters and literature - Australia's Culture Portal". Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "Henry Lawson: Australian writer - Australia's Culture Portal". Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Seal, Graham (1989). The Hidden Culture: Folklore in Australian Society. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-19-554919-8.

- "Comedian Anh Do wins indie book prize". ABC News. 15 March 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Oodgeroo Noonuccal." Encyclopedia of World Biography Supplement, Vol. 27. Gale, 2007

- Horton, David (1994). "Dance". The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history, society and culture, Vol. 1. Aboriginal Studies Press for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. pp. 255–7. ISBN 978-0-85575-234-7.

- Sweeney, D. 2008. "Masked Corroborees of the Northwest" DVD 47 min. Australia: ANU, Ph.D.

- The Australian Ballet (20 May 2020). "Our History". The Australian Ballet. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "The Australian Ballet Story". The Australian Ballet Story. And following pages. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Mitchell, Tony (1 April 2006). "The New Corroboree". The Age. Melbourne.

- "The Man must make his music". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 March 2007.

- "Waltzing Maltida a little ditty, historians say". ABC News. 5 May 2008. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- Gordon, Alan Atwood and Michael (30 September 2020). "From the Archives, 2000: A perfect party to end the world's greatest Games". The Age. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "How to Do a Bush Dance". Home.hiwaay.net. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "The Bushwackers – The Australian Band". THebushwackers.com.au. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- Oxford, A Dictionary of Australian Music, Edited by Warren Bebbington, Copyright 1998

- Davidson, Jim. "Melba, Dame Nellie (1861–1931)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 13 December 2018 – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- "John Antill : Represented Artist Profile : Australian Music Centre". Australianmusiccentre.com.au. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Australian pop music - Australia's Culture Portal". Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- Sturma, Michael. "O'Keefe, John Michael (Johnny) (1935–1978)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 13 December 2018 – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- "Biography". Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- "Civics | Paul Kelly (1955–)". Archived from the original on 2 June 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Dave" Laing, "Slim Dusty: Country singer famous for A Pub With No Beer", The Guardian (UK), 20 September 2003

- "Australian Indigenous ceremony - Australia's Culture Portal". Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "The Recruiting Officer & Our Country's Good – Stantonbury Campus Theatre Company, 2000". Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Theatre Royal - a great night out! - Hobart Tasmania". Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Princess Theatre - Jersey Boys ticket packages". Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "Melbourne Athenaeum Library - History of the Melbourne Athenaeum". Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- "Queen's Theatre". Archived from the original on 21 February 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "The Capitol Theatre - Sydney". Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "The man behind Dame Edna Everage". BBC News. 15 June 2007.

- "NIDA About Us - National Institute of Dramatic Art - NIDA". Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- "History - Adelaide Festival Centre". Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- "Robert Helpmann". Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Sydney Opera House". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "About". Sydney Theatre Company. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Review: Ngapartji Ngapartji, Belvoir Street Theatre". Dailytelegraph.com.au. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

External links

- ARTS.org.au – The Australian Arts Community – "An online resource for artists and arts organisations Australia wide."

- Australian Aboriginal Art Museum "La grange", Môtiers/NE, Switzerland

- Australia Council for the Arts

- Culture and Recreation Portal Archived 19 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Australian Art

- ArtsHub – Australian Arts Networking and Jobs Directory