Venues of the 1996 Summer Olympics

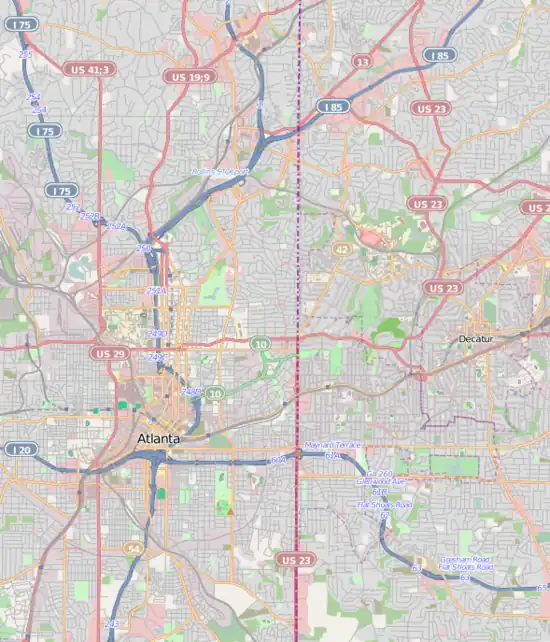

A total of twenty-nine sports venues were used for the 1996 Summer Olympics.

| Part of a series on |

| 1996 Summer Olympics |

|---|

|

Several sports venues for the 1996 Olympics were built before the 1960s as college venues. The first professional teams in Atlanta came in 1966, when Major League Baseball's Atlanta Braves moved from Milwaukee and the NFL added the Atlanta Falcons as an expansion team. In 1968, the NBA came to the city when the Atlanta Hawks arrived from St. Louis, and the NHL arrived four years later with the expansion Atlanta Flames.

The Braves and Falcons shared Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium from 1966 through 1991, after which the Falcons moved into the Georgia Dome, playing at that stadium from 1992 through 2016. The Braves would remain at the former stadium through the 1996 season. The Hawks initially played at Alexander Memorial Coliseum, now McCamish Pavilion, on the campus of Georgia Institute of Technology before the Omni Coliseum was completed in 1972 for both the Hawks and Flames. After the 1979–80 season, the Flames left for their current home of Calgary.

Bidding for the 1996 Games was held in 1990. Seventy-five percent of the venues used for the 1996 Games were owned by the state of Georgia. One of the new venues, the Georgia International Horse Park, had organization problems for the modern pentathlon event that included the competitors being forced to sit under an oak tree during the riding part of the event. The Georgia World Congress Center hosted the dramatic weightlifting 64 kg event that involved national tensions between Greece and Turkey.

After the Olympics, the Olympic Stadium, as intended from its construction, was converted into the baseball park Turner Field, which opened in 1997. That same year, both Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium and the Omni Coliseum were imploded within one week of one another. Philips Arena (since renamed State Farm Arena) was built upon the former Omni's footprint and opened in 1999, while the area where Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium stood is now a parking lot near Turner Field. The Braves vacated Turner Field after their 2016 season to move to a new ballpark in Cobb County now known as Truist Park; Georgia State University acquired Turner Field and its surrounding parking lots in January 2017 and converted the former Olympic Stadium a second time into the venue now known as Center Parc Stadium to host their college football program.

Olympic Ring

Metro Atlanta

| Venue | Sports | Capacity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atlanta Beach | Volleyball (beach) | 12,600 | [1][17] |

| Georgia International Horse Park | Cycling (mountain bike), Equestrian, Modern pentathlon (riding, running) | 32,000 | [7][18] |

| Lake Lanier | Canoeing (sprint), Rowing | 17,300 | [19][20] |

| Stone Mountain Park Archery Center and Velodrome | Archery, Cycling (track) | 5,200 (archery) 6,000 (cycling track) |

[15][21] |

| Stone Mountain Tennis Center | Tennis | 27,500 | [22][23] |

| Wolf Creek Shooting Complex | Shooting | 7,500 | [22][24] |

Other venues

| Venue | Location | Sports | Capacity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Florida Citrus Bowl | Orlando, Florida | Soccer | 65,000 | [1] |

| Golden Park | Columbus, Georgia | Softball | 8,800 | [19][25] |

| Legion Field | Birmingham, Alabama | Soccer | 81,700 | [19] |

| Ocoee Whitewater Center | Ducktown, Tennessee | Canoeing (slalom) | 14,400 | [5][26] |

| Orange Bowl | Miami | Soccer | 74,476 | [15] |

| Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium | Washington, D.C. | Soccer | 56,500 | [15] |

| Sanford Stadium | Athens, Georgia | Soccer (final) | 86,100 | [15][27] |

| Stegeman Coliseum | Athens, Georgia | Gymnastics (rhythmic), Volleyball (indoor) | 10,000 | [22][28] |

| Wassaw Sound | Savannah, Georgia | Sailing | 1,000 | [22][29] |

Before the Olympics

Before professional sports came to Atlanta and the Southern United States in the 1960s, college sports were followed in a manner similar to that of professional sports in the New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Midwestern part of the United States. The oldest of the venues in the South used for the 1996 Games was Legion Field in Birmingham, Alabama, which opened in 1926 and used from 1948 to 1988 for the Iron Bowl college football rivalry between Auburn University and the University of Alabama, a game that now alternates between the two schools' on-campus stadiums.[30][31] Legion Field hosted the SEC Championship Game for the first two seasons of 1992 and 1993 before the venue moved to Atlanta and the Georgia Dome in 1994, where it had remained until the closure of the Georgia Dome in 2017.[32][33][34][35] The SEC Championship Game is currently hosted at Mercedes Benz Stadium in Atlanta, the successor to the Georgia Dome. Three years after Legion Field was completed, Sanford Stadium opened on the University of Georgia campus in Athens, and has undergone several expansions since its opening.[36] The Citrus Bowl in Orlando, Florida opened in 1936, and has undergone several expansions of its own.[37] In Miami, the Orange Bowl (known as Burdine Stadium until 1959) opened the following year, and served as the home of the University of Miami Hurricanes, who played in the stadium from its opening until its closure in 2007.[38] Alexander Memorial Coliseum on the Georgia Tech campus opened in 1956.[39]

In 1961, the District of Columbia Stadium opened in Washington, D.C., with the National Football League (NFL) Washington Redskins losing 24–21 to the New York Giants.[40] The Stadium (renamed Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) Memorial Stadium in 1969 in honor of Robert F. Kennedy, who had been assassinated the previous June) served as home of the second Washington Senators Major League Baseball (MLB) team from 1961 to 1971, when they moved to Dallas, Texas the following year and were renamed the Texas Rangers (the first Senators team were in Washington from 1901 to 1960 before relocating to Minneapolis in 1961 and being renamed the Minnesota Twins, a name they have retained to this day).[41][42][43][44][45][46]

Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium (Atlanta Stadium: 1965–76) opened on April 12, 1966, with the Braves MLB franchise debuting following their move from Milwaukee after the 1965 season with a 3–2 loss to the Pittsburgh Pirates.[47][48] That same year in the NFL, the expansion Atlanta Falcons debuted with a 19–14 loss to the Los Angeles Rams.[49] Fulton County Stadium (known locally) would serve as host to the Peach Bowl from 1971 to 1991 before moving to the Georgia Dome, where it remained from the 1992 bowl season until 2016.[50] In baseball, Fulton County Stadium hosted the 1972 MLB All-Star Game.[51] The Stadium would host three World Series in the 1990s before the Olympics, losing twice (1991 to the Twins in seven games and 1992 to the Toronto Blue Jays in six games, and winning once (1995 over the Cleveland Indians in six games.).[52][53][54][55] The Falcons would remain at Fulton County Stadium until the 1991 NFL season, then moved to the Georgia Dome the following season, where they remained through the 2016 season.[56][57]

The Georgia Dome hosted Super Bowl XXVIII, where the Buffalo Bills lost 30–13 to the Dallas Cowboys. It was the Bills' second straight Super Bowl loss to the Cowboys and fourth straight Super Bowl loss overall.[58]

The same year the Falcons debuted in the NFL, the Miami Dolphins made their debut in the American Football League (AFL) at the Orange Bowl.[59] The Dolphins would join the NFL in 1970 following the AFL–NFL merger.[60] They would remain at the Orange Bowl until the 1987 NFL season, when they moved to Joe Robbie Stadium (now Hard Rock Stadium) the following year, which they have remained at to this day.[61][62] Five of the first thirteen Super Bowls took place at the Orange Bowl, including Joe Namath's New York Jets defeating Johnny Unitas's Baltimore (now Indianapolis) Colts 16–7 in Super Bowl III.[63][64][65][66][67]

Following the 1967–68 National Basketball Association (NBA) season, the Hawks franchise moved from St. Louis, Missouri to Atlanta for the 1968–69 season.[68][69] The Hawks spent their first four seasons at Alexander Memorial Coliseum until construction at the Omni Coliseum (known locally as the Omni) was completed in 1972.[70] The same season the Hawks moved into the Omni also saw the debut of the National Hockey League's Atlanta Flames as cohabitants.[71][72] The Flames would remain in Atlanta until the 1979–80 season before moving up to Calgary, Alberta, Canada the following season, where they have remained ever since.[73][74] For the 1980–81 to the 1982–83 NHL season, the now-Calgary Flames played in the Stampede Corral, then moved to the Olympic Saddledome (now Scotiabank Saddledome) for the 1983–84 season, where they remain to this day.[74][75][76] Both Stampede Corral and the Saddledome served as venues for the Winter Olympics, when Calgary hosted in 1988.[77] Other noted events hosted by the Omni were the 1977 NCAA Men's Final Four, the 1978 NBA All-Star Game, the 1988 Democratic National Convention, and the 1993 NCAA Women's Final Four.[78][79][80][81]

For the 1994 FIFA World Cup, RFK Stadium and the Citrus Bowl served as venues, including Round of 16 games. RFK Stadium's round of 16 game was between Spain and Switzerland, while the Citrus Bowl's was between the Republic of Ireland and the Netherlands.[82][83]

Atlanta was awarded the 1996 Olympics at the 1990 International Olympic Committee meeting in Tokyo.[84] Seventy-five percent of the existing sites used for the games were on property owned by the state of Georgia.[85] Fifty additional sites would be acquired to use for logistical needs.[85] Venue design lasted from July 1992 to the end of 1994 for new venues, while construction lasted from 1993 to March 1996. Among the new venues constructed, expanded, or retrofitted were Olympic Stadium (known locally at the time as Centennial Olympic Stadium), the Georgia International Horse Park in Conyers (east of Atlanta), and the sailing (then yachting) venue at Wassaw Sound in Savannah.[86] The velodrome and archery venues at Stone Mountain Park were temporary venues for the Games, with the velodrome track purchased in 2002 and moved to Bromont, Quebec.[87]

During the Olympics

Olympic Stadium witnessed American Carl Lewis win his fourth straight Olympic gold medal in the men's long jump. Lewis tied Al Oerter, who won four straight Olympic gold medals in the men's discus throw from 1956 to 1968. Oerter, who carried the Olympic flame into the stadium during the opening ceremony before handing it off to boxer Evander Holyfield, embraced Lewis after his win.[88]

Ocoee Whitewater Center on the Toccoa/Ocoee River was dry until 1950, though it was redirected into the dry riverbed in 1994. Water was released for 77 days into the course for training, a pre-Olympic event, and the Olympics themselves.[89]

Rain on the streets of Atlanta affected two of the four road cycling events. During the men's individual road time trial event, the race was held in an intermittent rain that became a deluge with the middle starters that created up to 6 in (15 cm) of flooding in downtown Atlanta. It cleared up by the time the last ten riders started their runs.[90] In the women's individual road race, a downpour occurred midway through the event, causing several racers to skid and fall as a result.[91]

The Georgia International Horse Park (known locally as the Horse Park) had the endurance part of the eventing competition begin at 7:00 A.M. EDT to combat Georgia's torrid summer heat. Mesh protected unshaded parts of the course to filter out ultraviolet light, and misting fans were used to cool the horses along with 80 veterinarians on site and three available equine ambulances.[92] In the individual dressage event at the Horse Park, kür, or freestyle dressage to music, was added to the competition. Germany's Isabell Werth on Gigolo came from behind to win gold, performing a medley that included "Just a Gigolo" and Monty Python's "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life".[93] Organizing issues in the modern pentathlon event affected spectators in their travels from downtown Atlanta to the Horse Park in Conyers 37 mi (60 km) away. This included lack of shuttle buses from parking to the competition sites 5 mi (8.0 km), forcing spectators to walk that distance. Modern pentathletes had to sit under one shady part of the oak tree during the riding portion of the event.[94]

During the men's 10 m air pistol shooting event at Wolf Creek, the ninth round of the final was halted when a fallen tree hit a power line and knocked out the electronic scoring system. The competition resumed after several minutes of delay. Italy's Roberto Di Donna came from behind to defeat China's Wang Yifu by 0.1 point. Wang collapsed in his chair and fainted suddenly. Stretcher bearers had trouble finding the medical center, but Wang recovered to take part in the men's free pistol event three days later.[95]

Georgia World Congress Center witnessed two dramatic events. At the table tennis women's singles final on July 31, a five-game final between China's Deng Yaping and Chinese Taipei (Taiwan/Republic of China)'s Chen Jing took place that had Deng leading 2–0 in the third game that was tied at 15 when a delay occurred. Taiwan was under IOC rules (since 1980) to compete as Chinese Taipei to appease the People's Republic of China and could not use the national flag of Taiwan. One fan in the stand displayed his own Taiwanese flag, resulting in police arriving to remove him from the audience. Another fan responded by punching a policeman in the mouth, and was also removed. Chen won the third game when play resumed, then tied the final by winning the fourth game. Deng won the deciding game decisively to win the gold medal.[96] Nine days earlier in the men's 64 kg (featherweight) weightlifting event, a battle between Turkey's Naim Süleymanoğlu and Greece's Valerios Leonidis had Greek fans sit on one side of the stands of the hall where the weightlifting events were held, while the Turkish fans sat on the other side of the stands. The 2.5 hour final had the audience give both Süleymanoğlu and Leonidis standing ovations that was won by the Turk.[97]

After the Olympics

The Georgia World Congress Center, first opened in 1976 and expanded twice before the 1996 Olympics, was expanded again in 2002.[98] As of 2010, the three buildings containing the twelve total exhibit halls had a total of 1,366,000 sq ft (126,900 m2).[99]

The Georgia Tech Aquatic Center opened in 1977 as the Student Athletic Center. The venue was converted into the Aquatic Center for the 1996 Games. It was enclosed in 2004 and renamed the Georgia Tech Campus Recreation Center, which remains in use today.[100]

The temporary structures at Stone Mountain Park were removed after the 1996 Olympics. As of 2010, the former archery and track cycling venues are part of the songbird and habitat trail.[101]

Lake Lanier hosted the ICF Canoe Sprint World Championships in 2003, the only time they have ever been held in the United States.[102]

Atlanta Beach (now the Clayton County International Park) and the Horse Park continue to be used as of 2010 in their local communities of Jonesboro and Conyers, respectively.[103][104]

The Hawks remained at the Omni for the 1996–97 NBA season.[105] Following that season, the Hawks moved back to Georgia Tech's Alexander Memorial Coliseum.[39] On July 26, 1997, the Omni was imploded to make way for a new arena for the Hawks and the NHL's expansion Thrashers.[106] Alexander Memorial Coliseum and the Georgia Dome both served as home for the Hawks for the 1997–98 and 1998–99 seasons while the new venue built on the site of the former Omni was being constructed.[39][107][108] The new arena opened in September 1999 as Philips Arena and the Hawks moved in.[109][110] That same year, the Thrashers moved into Philips to join the NHL.[111] The Hawks continue to use Philips Arena, since renamed State Farm Arena, to this day,[112] while the Thrashers would leave Atlanta after the 2010–11 season[113] and become the current version of the Winnipeg Jets.[114] On August 29, 2018, Philips Arena was renamed State Farm Arena, coinciding with a $192.5 million renovation to the arena.[112]

The 1996 season would be the last for the Braves at Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium.[115] Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium played host to three games of the 1996 World Series, where the team lost to the New York Yankees in six games.[116] Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium was imploded on August 2, 1997, and is now a parking lot adjacent to the former Olympic Stadium.[117]

Following the 1996 Summer Paralympics, Olympic Stadium was retrofitted between September 1996 and April 1997, with the synthetic 400 m athletic track and 35,000 seats removed.[118][119] The new venue, named Turner Field in honor of then-Braves owner and former Goodwill Games founder Ted Turner, opened on April 4, 1997, with a 5–4 win over the Chicago Cubs.[119][120] Turner Field hosted two games of the 1999 World Series (swept by the Yankees in four games) and the 2000 MLB All-Star Game.[121][122] On November 12, 2013, the Braves organization announced that the team would move into a new ballpark located in Cobb County, SunTrust Park, in time for the 2017 season. SunTrust Banks, the original naming rights holder, merged with BB&T in 2019, creating Truist Financial; the ballpark was renamed Truist Park in January 2020.[123] Then-Atlanta mayor Kasim Reed stated that the stadium site would be redeveloped once the Braves vacated Turner Field.[124] The Braves' final game at Turner Field took place on October 2, 2016, with a 1–0 win over the Detroit Tigers. In May 2014, Georgia State University announced its intentions to pursue the 77-acre (310,000 m2) Turner Field site for a mixed-use development. One proposed development plan included reconfiguring Turner Field into a 30,000 seat (American) football stadium and building a new baseball field on the footprint of the former Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium, incorporating the wall where Hank Aaron hit his historic 715th home run. An alternate proposal submitted in November 2015 would adaptively reuse portions of the ballpark for a mixed housing and retail development, while a new American football-specific stadium would be built to the north, along with the aforementioned new baseball field.[125][126] On December 21, 2015, the Atlanta Fulton County Recreation Authority announced that it had accepted Georgia State's bid for the stadium property.[127] On August 18, 2016, Georgia State and the Atlanta–Fulton County Recreation Authority reached a tentative purchase agreement for Turner Field, and the purchase and redevelopment plan was approved by the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia on November 9, 2016. On January 5, 2017, the sale of Turner Field was officially closed, and the former ballpark was redeveloped into Georgia State Stadium starting in February 2017.[128][129][130] The stadium conversion occurred over multiple phases, with the first phase completed in time for Georgia State's home opener on August 31, 2017.[131] The venue was renamed to the current Center Parc Stadium in 2020 via a sponsorship deal with the Atlanta Postal Credit Union, doing business as Center Parc Credit Union.[132]

The Georgia Dome hosted Super Bowl XXXIV in 2000, when the then-St. Louis Rams (who have since relocated back to Los Angeles in 2016) defeated the Tennessee Titans 23–16 in a game that came down to the final play.[133] The venue also played host to the NCAA Men's Final Four in 2002, 2007, and 2013.[134][135][136] The Dome was home to the football program of nearby Georgia State University from the team's inception in 2010 until 2016, after which the team moved to Georgia State Stadium.[137] The Falcons' final game in the Dome took place on January 22, 2017, with a 44–21 win over the Green Bay Packers in the 2016 NFC Championship Game. The Dome was closed after its final public event on March 5, 2017, and the stadium was demolished by implosion on November 20, 2017.[138] Its replacement, Mercedes-Benz Stadium, located just south of the Dome, opened on August 26, 2017.[139] Most of the former Georgia Dome site became greenspace for tailgating at Mercedes-Benz Stadium and other community events; a 600-car parking garage and a high-rise convention center hotel are also planned for the site.[140] On April 17, 2014, Falcons owner Arthur Blank was awarded the Major League Soccer (MLS) expansion franchise Atlanta United FC, which began play in 2017 and shares Mercedes-Benz Stadium with the Falcons; however, due to construction delays with Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the soccer club played its home matches at Georgia Tech's Bobby Dodd Stadium, which was not used during the Olympics, during the first half of the 2017 MLS season.[141]

RFK Stadium remained in use for (American) football, baseball, and soccer for many years after the Games. In football, it hosted its last NFL game on December 22, 1996, with a 37-10 Redskins victory over the Dallas Cowboys.[142] The Redskins, since renamed as the Washington Commanders, moved to Jack Kent Cooke Stadium (now FedExField) in Landover, Maryland (east of Washington, D.C.) the following season, making their debut at the stadium with a 19–13 overtime win over the Arizona Cardinals.[143] Football would return to the stadium in 2008 with the debut of the EagleBank Bowl, a college football bowl game renamed the Military Bowl for 2010.[144] The Military Bowl would continue to be held at RFK through the 2012 edition, after which it was moved to Navy–Marine Corps Memorial Stadium in Annapolis, Maryland.[145]

For the 2005 MLB season, RFK was put into use once again as a baseball venue after the relocation of the Montreal Expos to become the Washington Nationals. The Expos left their previous home at Olympic Stadium in Montreal, a 1976 Summer Olympic venue, after the 2004 season.[146][147] The Nationals made their debut at RFK a winning one, defeating the Arizona Diamondbacks 5–3 on April 14, 2005.[148] The Nationals' final game at RFK Stadium was on September 23, 2007 with a 5–3 win over the Philadelphia Phillies.[149] The team opened its 2008 season in the new Nationals Park, also in the District, where it has remained ever since.[150]

RFK Stadium has seen its most enduring post-Olympics use as a soccer venue. It has been home to the Major League Soccer team D.C. United since the league's creation in 1996, and also hosted the MLS All-Star Game in 2002 and 2004.[151] The Washington Freedom, a women's team originally in the defunct Women's United Soccer Association (WUSA), played its home games at RFK during the league's entire existence from 2001 to 2003. In 2009, the WUSA would be effectively relaunched as Women's Professional Soccer (WPS), with the Freedom returning as charter members and playing occasional home games at RFK.[151] The stadium is no longer used for women's club soccer, as WPS folded just before its scheduled 2012 season, and the Washington team in the current National Women's Soccer League does not use RFK. In the 2003 FIFA Women's World Cup, RFK Stadium hosted six games that included a 1–1 tie between Brazil and France.[152] It has also hosted the USA men's national team 20 times, with the USA winning 12 of the matches—the most wins by the US at any single stadium.[151] On February 27, 2017, D.C. United broke ground for a new soccer-specific stadium, Audi Field, to be located near Nationals Park.[153] The final D.C. United home match at RFK took place on October 22, 2017, with a 2–1 loss to the New York Red Bulls.[154] D.C. United opened Audi Field on July 14, 2018, with a 3–1 win over the Vancouver Whitecaps FC.[155] On September 5, 2019, Events DC, the operator of RFK Stadium, announced plans to demolish the stadium by 2021 due to the lack of a major tenant and rising maintenance costs.[156]

The Orange Bowl was demolished in 2008,[38] with the site now redeveloped as Marlins Park, since renamed LoanDepot Park, a baseball stadium which now serves as the home of the Miami Marlins (formerly the Florida Marlins). The Miami Hurricanes moved to Dolphin Stadium (now Hard Rock Stadium) after the Orange Bowl's closure and demolition, sharing a home stadium with the NFL's Dolphins for the second time; the Hurricanes and Dolphins had previously shared the Orange Bowl from the Dolphins' AFL inception in 1966 until the 1986 NFL season, when what would become Hard Rock Stadium opened.

The Orlando Citrus Bowl Stadium continued to host the UCF Knights football team until the end of the 2006 season, after of which the team moved into their own on-campus stadium. In an effort to modernise the Citrus Bowl, the stadium's lower bowl was demolished and rebuilt during most of 2014.[157] The renovated stadium officially reopened on November 19, 2014.[158] The stadium, since renamed Camping World Stadium, was home to the Major League Soccer team Orlando City SC and its sister team in the National Women's Soccer League, the Orlando Pride, through their respective 2016 seasons; both teams moved into Orlando City's own soccer-specific stadium for the 2017 MLS and NWSL seasons.

Alexander Memorial Coliseum remains home to the Georgia Tech men's and women's basketball teams. In 2010, the Institute announced that the facility would undergo a major renovation, and would be renamed McCamish Pavilion, after the patriarch of the family that contributed one-third of the $45 million cost. During the 2011–12 season, the teams played at Philips Arena and the Arena at Gwinnett Center, now Gas South Arena, in suburban Duluth; the renovated arena reopened in November 2012.[159]

References

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 539. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 452. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 450. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 458. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 542. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 170. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 540. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. pp. 451, 456. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. pp. 448, 460. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. pp. 540-1. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. pp. 448, 455, 457, 459-60, 462, 466. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 108. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 451. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 449. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 543. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 465. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 464. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. pp. 453-4, 460. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 541. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. pp. 452, 460. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. pp. 448, 453. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 544. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. pp. 448, 453. Accessed 9 September 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 460. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 462. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 164. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 455. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 457. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Volume 3. p. 467. Accessed 9 December 2010.

- Encyclopediaofalabama.org profile of the Iron Bowl. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Informationbirmingham.com profile of Legion Field. Archived 2010-12-01 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Sports-reference.com 1992 Alabama Crimson Tide schedule and results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Sports-reference.com 1993 Florida Gators schedule and results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Sports-reference.com 1994 Florida Gators schedule and results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- "LSU overwhelms Georgia in second half to claim SEC title". ESPN. Associated Press. December 3, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- Georgiadogs.com profile of Sanford Stadium. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Orlandovenues.net history of the Citrus Bowl. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Orangebowlstadium.com History of the Orange Bowl. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- ramblinwreck.cstv.com profile of the Alexander Memorial Coliseum. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Washington District of Columbia Stadium 1 October 1961 WAS-NYG results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com 1901 Washington Senators (I) season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com 1960 Washington Senators (I) season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com 1961 Minnesota Twins season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com 1961 Washington Senators (II) season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com 1971 Washington Senators (II) season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com 1972 Texas Rangers season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB Atlanta Stadium 12 April 1966 PIT-ATL results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 1965 Milwaukee Braves season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Atlanta Stadium 11 September 1966 LA-ATL results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- www.chick-fil-abowl.com History of the Chick-fil-A (formerly Peach) Bowl. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB Atlanta Stadium 25 July 1972 All-Star Game results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 1991 World Series results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 1992 World Series results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Aldaver.com History of bid voting for the Olympic Games: 1896-2016. Accessed 10 December 2010. Archived 25 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 1995 World Series results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL 1991 Atlanta Falcons season. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL 1992 Atlanta Falcons season. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com Super Bowl XXVIII Atlanta Georgia Dome 30 January 1994 DAL-BUF results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com AFL 1966 Miami Dolphins season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL 1970 Miami Dolphins season results. Archived 2010-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL 1987 Miami Dolphins season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL 1988 Miami Dolphins season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Super Bowl II Miami Orange Bowl 14 January 1968 GB-OAK results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Super Bowl III Miami Orange Bowl 12 January 1969 NYJ-BAL results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Super Bowl V Miami Orange Bowl 17 January 1971 BAL-DAL results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Super Bowl X Miami Orange Bowl 18 January 1976 PIT-DAL results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Super Bowl Miami Orange Bowl XIII 21 January 1979 PIT-DAL results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1967-68 St. Louis Hawks season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1968-69 Atlanta Hawks season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1971-72 Atlanta Hawks season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1972-73 Atlanta Hawks season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Hockey-reference.com NHL 1972-73 Atlanta Flames season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Hockey-reference.com NHL 1979-80 Atlanta Flames season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Hockey-reference.com NHL 1980-81 Calgary Flames season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Hockey-reference.com NHL 1982-3 Calgary Flames season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Hockey-reference.com NHL 1983-84 Calgary Flames season results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- 1988 Winter Olympics official report. Archived 2011-01-14 at the Wayback Machine Part 1. pp. 152-7, 160-3. Accessed 10 December 2010. (in English and French)

- NCAAhoops.net 1977 Final Four bracket information. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Basketball NBA All Star-Game Atlanta Omni Coliseum 5 February 1978 results. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Ourcampaigns.com profile of the 1988 Democratic National Committee convention. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Webcitation.org profile of the 1993 NCAA Women's Final Four. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- FIFA.com World Cup Washington RFK Stadium 2 July 1994 ESP-SUI Round of 16 results. Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 10 December 2010.

- FIFA.com World Cup Orlando Citrus Bowl 4 July 1994 NED-IRL Round of 16 results. Archived 24 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 10 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 2. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 115. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. pp. 116-8. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- 1996 Summer Olympics official report. Volume 1. p. 118. Accessed 10 December 2010.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Track & Field (Men): Long Jump". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. pp. 225-6.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Canoeing: Men's Kayak Slalom Singles". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. p. 485.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Cycling: Men's Road Time Trial". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. p. 512.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Cycling: Women's Road Race". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. pp. 535-6.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Equestrian: Three-Day Event, Individual". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. p. 565.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Equestrian: Dressage, Individual". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. p. 589.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Modern Pentathlon: Men's Individual". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. pp. 773-4.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Shooting: Men's Air Pistol". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. p. 857.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Tablte Tennis: Women's Singles". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. p. 1011.

- Wallechinsky, David and Jaime Loucky (2008). "Weightlifting: Men's Featherweight". In The Complete Book of the Olympics: 2008 Edition. London: Aurum Press Limited. pp. 1072-73.

- gwcc.com Georgia World Congress Center history. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- gwcc.com Georgia World Congress Center fast facts. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Georgia Tech Campus Recreation Center profile. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Driving Map: Stone Mountain Park (2009). Pamphlet. Stone Mountain, Georgia: Stone Mountain Park.

- Sports123.com ICF Canoe Sprint World Championships men's K-1 1000 m 1938-2010 results. Archived 2011-05-18 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 11 December 2010 (Lake Lanier listed as Gainesville since that is the closest city to the lake.).

- Claytonparks.com profile of Clayton County International Park. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Georgia International Horse Park official website. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1996-97 Atlanta Hawks season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Hockey.ballparks.com profile of The Omni. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1997-98 Atlanta Hawks season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1998-99 Atlanta Hawks season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Philips Arena official website. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Basketball-reference.com NBA 1999–2000 Atlanta Hawks season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Hockey-reference.com NHL 1999–2000 Atlanta Thrashers season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Vivlamore, Chris (August 29, 2018). "Hawks reach arena naming rights agreement with State Farm". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- "NHL Board of Governors approves sale of Thrashers to True North Sports & Entertainment" (Press release). Winnipeg Jets. June 21, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- Tait, Ed; Kirbyson, Geoff (June 25, 2011). "Fans get their wish". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 1996 Atlanta Braves season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 1996 World Series results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Ballparktour.com profile of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Paralympic.org profile of the 1996 Summer Paralympics. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- MLB.com profile of Turner Field's history. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB Atlanta Turner Field 4 April 1997 ATL-CUB results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 1999 World Series results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB Atlanta Turner Field 11 July 2000 All-Star Game results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Bowman, Mark (January 14, 2020). "Braves unveil Truist Park as new stadium name". MLB.com. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- "Atlanta to demolish Turner Field". ESPN. Associated Press. November 12, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- Roberson, Doug (7 May 2014). "Georgia State wants to turn Turner Field into football stadium". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- Richards, Doug. "Georgia State: Build two new stadiums at Turner Field". WXIA. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Leslie, Katie; Trubey, J. Scott. "Turner Field to be sold to Georgia State and developer Carter". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Davis, Janet; Suggs, Ernie; Trubey, J. Scott. "Georgia State, partners reach deal to buy Turner Field for $30 million". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- Brown, Molly; Trubey, Scott. "Georgia State's $53M Turner Field redevelopment plan approved". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- "Georgia State, Private Development Venture Finalize Acquisition of Turner Field Site". Georgia State University. 5 January 2017. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- McQuade, Alex. "Georgia State begins construction on Turner Field". WXIA. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Center Parc Credit Union Announces Naming-Rights Sponsorship for Georgia State Stadium" (Press release). Georgia State University. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- Pro-football-reference.com Super Bowl XXXIV Atlanta Georgia Dome 30 January 2000 STL-TEN results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Sports-reference.com NCAA Men's Final Four 2002 results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Sports-reference.com NCAA Men's Final Four 2007 results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- msn.foxsports.com listing of the 2013 NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- "Georgia Dome". Georgia State Athletics. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- Tucker, Tim. "Georgia Dome implosion date set". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- "Fans say Mercedes-Benz Stadium is a real winner, despite Falcons loss". WSB-TV. 26 August 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Tucker, Tim (January 21, 2017). "What happens to Georgia Dome after NFC title game?". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- Stejskal, Sam. "Atlanta United to open Mercedes-Benz Stadium on July 30". MLS Soccer. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Washington RFK Stadium 22 December 1996 DAL-WAS results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Pro-football-reference.com NFL Landover, Maryland Jack Kent Cooke Stadium 14 September 1997 AZ-WAS results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- "D.C. game renamed Military Bowl". ESPN. Associated Press. October 26, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- Patterson, Chip (May 20, 2013). "Military Bowl moving to Annapolis, adds Conference USA for '13". CBSSports.com. Eye on College Football blog. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 2004 Montreal Expos season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB 2005 Washington Nationals season results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB Washington RFK Stadium 14 April 2005 AZ-WAS results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Baseball-reference.com MLB Washington RFK Stadium 23 September 2007 PHI-WAS results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- MLB.com profile of Nationals Park. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- "Military Bowl: History". Military Bowl. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- FIFA.com Women's World Cup Washington RFK Stadium 27 September 2003 FRA_BRA results. Accessed 11 December 2010.

- Rodriguez, Alicia (February 16, 2017). "DC United announce stadium groundbreaking ceremony on February 27". MLSsoccer.com. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- "DC United 1, New York Red Bulls 2 | 2017 MLS Match Recap". 22 October 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Giambalvo, Emily (July 14, 2018). "D.C. United debuts Audi Field, and Wayne Rooney, in a convincing win over Vancouver". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- McCartney, Robert (5 September 2019). "District to raze RFK Stadium by 2021 — but not necessarily so Redskins can build a new one". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Florida Citrus Bowl Reconstruction

- "Renovated Citrus Bowl unveiled after 10 months of reconstruction". Fox Sports. 19 November 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- Robertson, Doug (October 19, 2010). "Want to See the New Thrillerdome". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2012.