Transgender people in China

Transgender is an overarching term to describe persons whose gender identity/expression differs from what is typically associated with the gender they were assigned at birth.[1] Since "transgender studies" was institutionalized as an academic discipline in the 1990s, it is difficult to apply transgender to Chinese culture in a historical context. There were no transgender groups or communities in Hong Kong until after the turn of the century. Today they are still known as a "sexual minority" in China.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

Terminology

Because Chinese transgender studies are so unfocused, a wide variety of terms are used in relation to transgender in the varieties of Chinese.

- Tongzhi (同志, pinyin tóngzhi) refers to all peoples with a non-normative sexuality or gender, including homosexual, bisexual, asexual, transgender, and queer peoples.

- Bianxing (變性, biànxìng) is the most common way to say "change one's sex", though not necessarily through sexual reassignment surgery—bianxing may also include hormonal changes and lifestyle changes.[3]

- In Mandarin, the term kuaxingbie (跨性别, kùaxìngbié), literally "cutting across sex distinctions", has come into use as a literal translation of the English term "transgender", its use having proliferated from academic contexts.[4]

- Offensive terms for trans women include "niang niang qiang" (娘娘腔, meaning sissy boy) or "jia ya tou" (假丫头, meaning fake girl).[5]

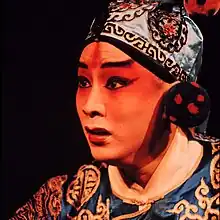

- "Fanchuan" (反串, fǎnchùan) is the historical term for cross-dressing performing on stage, as in Beijing opera where males play women's parts, or in Taiwanese opera where females play men's parts.

In Hong Kong, there are specific derogatory terms used towards transgender people. The most common is jan-jiu (人妖) which translates to "human monster".

- Bin tai, or biantai (變態) in Putonghua, in Hong Kong refers to a non-normative person, deviating from the reproductive heterosexual family and the normative body, gender, and sexuality expectations. It is also a derogatory term for cross-dressers, pedophiles, polygamists, homosexuals, masculine women, sissy boys, and transgender people.[6]

- Yan yiu, or renyao in Putonghua, translates into human ghost, human monster or freak. It is commonly used to target transgender people, but has historically been used for any kind of gender transgression.[7]

- The second form is naa-jing referring to men who are considered sissy or effeminate. However, the politically correct term for a transgender person in Hong Kong is kwaa-sing-bit (跨性別). The media in Hong Kong might use the negative term jan-jiu or bin-sing-jan, referring to a sex or gender changed person.[8][9]

- In the late 1990s, the performing group Red Top Arts (紅頂藝人, py Hǒngdǐng Yìrén) came to fame in Taipei, Taiwan as the island's first professional drag troupe. Since this time, "Red Top" and various homophones (紅鼎, 宏鼎, etc.) have come to be common combining-forms that indicates drag, cross-dressing, etc.

Terms for crossdressing are many and varied. 異裝癖 (py yìzhūangpǐ), literally "obsession with the opposite [sex's] attire", is commonly used. 扮裝 (py bànzhūang), literally "to put on attire", is commonly used to mean crossdressing. Related to this is an auxiliary term for drag queens: 扮裝皇后 (py bànzhūang húanghòu), or "crossdressing queen". There are several terms competing as translations of the English drag king, but none has reached currency yet.[10] While research shows that China's younger population is much more accepting of transgender people, offensive terminology like "jan-jim" or "bin-sing-jan" is very common.[2]

History of transgender people in China

In the mid 1930s, after the father of Yao Jinping (姚錦屏) went missing during the war with Japan, the 19-year-old reported having lost all feminine traits and become a man, was said to have an Adam's apple and flattened breasts, and left to find him.[11][12] Du He, who wrote an account of the event, insisted Yao had become a man,[11][13] while doctors asserted Yao was female.[13] The story was widely reported in the press,[13] and Yao has been compared to Lili Elbe, who underwent sex reassignment in the same decade.[11][13]

Cross dressing in Peking Opera

Sinologists often look to theatrical arts when imaging China in a transgender frame because of the prominent presence of cross-gender behavior.[14]

Peking Opera, also known as Beijing Opera, had male actors playing female dan characters. Men traditionally played women's roles due to women being excluded from performing in front of the public as a means of preventing carnal relations.[15] Although, before 1978, male to female cross dressing was mostly for theatrical performances, used for comedic effect or to disguise a character in order to commit a crime or defeat enemies. Female to male characters were considered heroic in theatrical performances.[16]

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties of China, cross dressing occurred both onstage and in everyday life. Within theater, some who were intrigued by it would roleplay, organize their own troupes, write, and perform theatrical pieces.[17]

Many of early modern China's stories reflected cross-dressing and living the life of a different gender for a short period of time, mainly featuring the cross-dressers as virtuous, like Mulan.[17]

Li Yu, a writer and entrepreneur, featured the gendering of bodies to be dependent upon men's desires and operated by a system of gender dimorphism, assumed by social boundaries of the time. When Li Yu created an acting troupe, as many elite males did, he had a concubine that played a male role as he believed she was "suited to male" or considered her more of the masculine gender.[17]

In modern-day Peking Opera and film, there are male to female cross dressers and vice versa for characters, especially with certain time periods.[18]

Early sexual change

According to some scholars, female infants were forced to dress up as males ("cross-dressing"). They claim that this, in turn, affected those children into living transgender lives.[17]

Laws regarding gender reassignment

Gender reassignment on official identification documents (Resident Identity Card and Hukou) is allowed in China only after the sex reassignment surgery. The following documents are required in order to apply for gender reassignment:[19]

- A formal written request from the applicant;

- Household Registration Book (which may need to be retrieved from the applicant’s family) and Resident Identity Card;

- A certificate of gender authentication issued by a domestic tertiary hospital, along with verification of the certificate from a notary public office or judicial accreditation body;

- A notice of permission for gender alteration [of the document] from the human resources office of the institution, collective, school, enterprise, or other work units of the individual (if applicable).

In China, trans women are required to notify family, prove they have no criminal record, and undergo psychological intervention in order to be allowed a prescription for hormone medication.[20] Familial disapproval had led many to seek alternative sources of their medication, including online sources.[21][22]

Based on the Management Specification on Gender Reassignment Technology published by National Health Commission in 2022, the surgical patient has to be at least over 18 years old, have the desire of intending gender reassignment persistently for more than 5 years, be unmarried in order to take the sex reassignment surgery;[23] plus, proof of familial consent is required prior to any surgical practice regardless of surgical types.[19]

In 2009 the Chinese government made it illegal for minors to change their officially-listed gender, stating that sexual reassignment surgery, available to only those over the age of twenty, was required in order to apply for a revision of their identification card and residence registration.[24]

In early 2014 the Shanxi province started allowing minors to apply for the change with the additional information of their guardian's identification card. This shift in policy allows post-surgery marriages to be recognized as heterosexual and therefore legal.[25]

In November 2022, Chinese government began preparations to restrict internet purchases of estradiol and cyproterone, and a draft had been reviewed.[26][27] The ban was put in place in December so that even those with prescriptions cannot buy these drugs online.[28]

Transgender support in China

The Beijing LGBT Center (Beijing Tongzhi Zhongxin) is primarily composed of four organizations: Aizhixing AIDS Organization, Tongyu Lala Organization, Aibai Cultural and Education Center, and Les+.[29] Tongyu Lala is an organization based in Beijing that combats discrimination against and is an advocate for social inclusion of lesbians, bisexual women, and transgender people. The group also helps organize LGBT groups in China.[30]

There are a number of important events that focus on promoting LGBT rights and equality in China, including the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia; the Beijing Queer Film Festival; and gay pride parades held in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou (see Hong Kong Pride Parade and Shanghai Pride).[29]

Transgender people and Chinese culture

Religion

Confucianism, one of the dominant value systems in China, enforces and promotes traditional gender roles. Confucianism has a strong belief in maintaining males as the head of the household; thus, transgender people are considered to usurp said gender roles.[31]

Buddhism views all bodily concerns as entrapment in the Samsara, equally including those concerns regarding LGBT+ identities and issues.[32]

Transgender culture

Youth

Transgender youth in China face many challenges. One study found that Chinese parents report 0.5% (1:200) of their 6 to 12-year boys and 0.6% (1:167) of girls often or always ‘state the wish to be the other gender’. 0.8% (1:125) of 18- to 24-year-old university students who are birth-assigned males (whose sex/gender as indicated on their ID card is male) report that the ‘sex/gender I feel in my heart’ is female, while another 0.4% indicating that their perceived gender was ‘other’. Among birth-assigned females, 2.9% (1:34) indicated they perceived their gender as male, while another 1.3% indicating ‘other’.[33]

One transgender man recounts his childhood as one filled with confusion and peer bullying. In school he was mocked for being a tomboy and was regularly disciplined by teachers for displaying rowdy boy-like behavior. Some recommended to his parents that he be institutionalized.[24]

These attitudes may be slowly changing and many Chinese youth are able to live happy and well-adjusted lives as members of the LGBT+ community in modern China.[5] In July 2012 the BBC reported that the new open economy has led to more freedom of sexual expression in China.[34]

In 2021, China's first clinic for transgender children and adolescents was set up at the Children's Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai to safely and healthily manage transgender minors' transition.[35]

According to a survey conducted by Peking University, Chinese trans female students face strong discrimination in many areas of education.[36] Sex segregation is found everywhere in Chinese schools and universities: student enrollment (for some special schools, universities and majors), appearance standards (hairstyles and uniforms included), private spaces (bathrooms, toilets and dormitories included), physical examinations, military trainings, conscription, PE classes, PE exams and physical health tests. Chinese students are required to attend all the activities according to their legal gender marker. Otherwise they will be punished. It is also difficult to change the gender information of educational attainments and academic degrees in China, even after sex reassignment surgery, which results in discrimination against well-educated trans women.[37][38]

Literature

Literature and plays in the 17th century featured cross-dressing, like Ming dramatist Xu Wei who wrote Female Mulan Takes Her Father’s Place in the Army and The Female Top Candidate Rejects a Wife and Receives a Husband. Despite the female to male cross dressing, the woman would eventually return to her socially gendered roles of wearing women's clothes and would marry a man.[17]

Social media and technology

Technological advancements help to promote greater awareness among youth of LGBT+ issues. Access to Western media such as trans-themed web sites and featuring of trans-identifying characters in Western movies are broadening the knowledge and sense of community that many trans youth seek.[5][39]

Transgender people in media

Entertainers:

Models:

- Liu Shihan

Citizens:

- Liu Ting[41]

The following Chinese films portray transgender characters:[2]

- Swordsman II (1992)

- The East is Red (1993)

- Whispers and Moans (2007)

- Splendid Float (2004)

- Drifting Flowers (2008)

In addition, in the 2019 documentary film, The Two Lives of Li Ermao, a trans migrant worker "transitions from male to female, then back to male," which some promoted as part of "Love Queer Cinema Week."[42]

See also

References

- "GLAAD Media Reference Guide – Transgender Issues". GLAAD. 2011-09-09. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Chiang, Howard (2012-12-11). Transgender China. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-230-34062-6.

- Baird, Vanessa (2003). 性別多樣化: 彩繪性別光譜. 書林出版有限公司. p. 25. ISBN 9789575869953. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- "Chung wai literary quarterly". 2002. p. 212. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- Shiu, Ling-po (2008). Developing Teachers and Developing Schools in Changing Contexts. Chinese University Press. pp. 298–300. ISBN 978-9629963774.

- Erni, John Nguyet (2018-12-07). Law and Cultural Studies: A Critical Rearticulation of Human Rights. Routledge. ISBN 9781317156215.

- Emerton, Robyn (2006). "Finding a voice, fighting for rights: the emergence of the transgender movement in Hong Kong". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 7 (2): 243–269. doi:10.1080/14649370600673896. S2CID 145122793. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Transgender China". Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Chiang, Howard (2012-12-11). Transgender China. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-230-34062-6.

- "Cantonese: Sex 黃色字眼". Cantonese.ca. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- P. Zhu, Gender and Subjectivities in Early Twentieth-Century Chinese Literature (2015, ISBN 1137514736), page 115.

- Chiang, Howard (2018). Sexuality in China: Histories of Power and Pleasure. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-0295743486.

- Chiang, Howard (2018). After Eunuchs: Science, Medicine, and the Transformation of Sex in Modern China. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chiang, Howard (2012-12-11). Transgender China. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-230-34062-6.

- "Transgender China". Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Zhang, Qing Fei (2014). "Transgender Representation by the People's Daily Since 1949". Sexuality & Culture. 18: 180–195. doi:10.1007/s12119-013-9184-3. S2CID 144742299.

- Kile, Sarah E. (Summer 2013). "Transgender Performance in Early Modern China". Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies. 24 (2): 131–145. doi:10.1215/10407391-2335085.

- Chengzhou He (2 December 2011). Performance and the Politics of Gender: Transgender Performance in Contemporary Chinese Film. Brown University. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Legal Gender Recognition in China: A Legal and Policy Review" (PDF). UNDP. 2018-08-05.

- Murphy, Colum. "China's First Clinic for Transgender Kids Opens in Shanghai". Bloomberg News.

- Yang, Caini (8 November 2022). "China's Plan to Ban Online Sale of Hormone Drugs Worries Trans Women". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- "国家药监局综合司公开征求《药品网络销售禁止清单(征求意见稿)》意见" [The State Drug Administration Department of comprehensive public consultation "drug network sales ban list (draft for comment)" comments]. www.nmpa.gov.cn. National Medical Products Administration. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- "G05 性别重置技术临床应用管理规范(2022年版)" (PDF). 中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会. May 2022.

- Jun, Pi (9 October 2010). "Transgender in China". Journal of LGBT Youth. 7 (4): 346–351. doi:10.1080/19361653.2010.512518. S2CID 143885704.

- Sun, Nancy (9 January 2014). "Shanxi Permits Persons to Change Gender Information". All-China Women's Federation. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Yang, Caini (8 November 2022). "China's Plan to Ban Online Sale of Hormone Drugs Worries Trans Women". Sixth Tone. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- "国家药监局综合司公开征求《药品网络销售禁止清单(征求意见稿)》意见" [The State Drug Administration Department of comprehensive public consultation "drug network sales ban list (draft for comment)" comments]. www.nmpa.gov.cn. National Medical Products Administration. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- De Guzman, Chad (21 March 2023). "A New Drug Law and Old Attitudes Threaten China's Trans Community". Time. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- Lixian, Holly (Nov–Dec 2014). "LGBT Activism in Mainland China". Against the Current. 29 (5): 19–23. ISSN 0739-4853.

- "LGBT Community in Beijing". Anglo Info. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Bolich, G. G. (2009). Crossdressing in Context, Vol. 4 Transgender & Religion. Lulu.com. pp. 351–354. ISBN 978-0-615-25356-5.

- Greenberg, Yudit Kornberg, ed. (2007). "Homosexuality in Buddhism". Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-85109-981-8.

- Winter, Sam; Conway, Lynn. "How many trans* people are there? A 2011 update incorporating new data". Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "China's acceptance of transgender people". BBC News. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Wenjun, Cai (November 5, 2021). "Nation's first transgender clinic opens in Shanghai". Shanghai Daily. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- "2017中国跨性别群体生存现状调查报告". MBA智库. Archived from the original on 2022-04-01. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- "跨性别者手术后:历时半年终于修改学历 就业遭歧视". 搜狐. 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- 王若翰 (2012-06-20). "变性人群体真实生态:唯学历证明无法修改性别" (Press release) (in Chinese (China)). 搜狐. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- Levine, Jill (8 August 2013). "Is Support for Transgender Rights Increasing in China?". Tea Leaf Nation. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Kirstin Cronn-Mills, Transgender Lives: Complex Stories, Complex Voices (2018, ISBN 1541557506), page 45.

- "Chinese media embraces trans star, reflecting attitude shift in Beijing". america.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- Knotts, Joey (9 November 2020). "German, Queer, and Animated: Beijing's Film Festivals This Month". The Beijinger. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

External links

- The Center for the Study of Sexualities, at Taiwan's National Central University.

- Chinese and Taiwanese gender-related information.

- TransgenderASIA Research Centre, A website on transgender research, focusing on Asian transgender persons and culture.

- A personal story from a transgender woman in China

- Being LGBT in Asia: China Country Report

- A transgender woman who start hormone at 12 start growing male characters after stopping female hormone in male prison for 7 months.

- China 'failing trans people' as young attempt surgery on themselves – study The Guardian, 2019