New Marriage Law

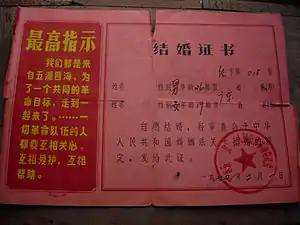

The New Marriage Law (also First Marriage Law, Chinese: 新婚姻法; pinyin: Xīn Hūnyīn Fǎ) was a civil marriage law passed in the People's Republic of China on May 1, 1950. It was a radical change from existing patriarchal Chinese marriage customs, and needed constant support from propaganda campaigns. It has since been superseded by the Second Marriage Law of 1980. It was formally repealed by the Civil Code in 2021.[1]

.svg.png.webp) |

|---|

|

|

Origins

Marriage reform was one of the first priorities of the People's Republic of China when it was established in 1949.[2] Women's rights were a personal interest of Mao Zedong (as indicated by his statement: "Women hold up half the sky"),[3] and had been a concern of Chinese intellectuals since the New Culture Movement in the 1910s and 1920s.[4] Traditionally, Chinese marriage had often been arranged or forced, concubinage was commonplace, and women could not seek a divorce.[2]

Implementation

The new marriage law was enacted in May 1950, delivered by Mao Zedong himself.[2] It provided a civil registry for legal marriages, raised the marriageable age to 20 for males and 18 for females, and banned marriage by proxy; both parties had to consent to a marriage. It immediately became an essential part of land reform, as women in rural communities stopped being sold to landlords. The official slogan was: "Men and women are equal; everyone is worth his (or her) salt."[5] As a result of yearly propaganda campaigns from 1950 to 1955 to popularize the law, more than 90% of marriages in China were registered, and thereby were considered to be compliant with the New Marriage Law. Nonetheless, Women's Federation reports indicated instances of violence when women attempted to exercise the rights to divorce granted to them by the law: The Shaanxi Women's Federation, for example, counted 195 instances of death related to marriage cases by the end of 1950 in that province.[6] As a method of implementation, the Women's Federation promoted and organized "Marriage Law Month" in 1953, as an attempt to dampen the conflict which followed the law's passing. Songs and operas were performed, to show the downfall of the "old ways".[7]

Effect on marriage registration

The New Marriage Law that was established also had a new effect on the registration system that existed in China. The law provided equality not only for women, but also warranted partners to have free choice in terms of marriage. Under the new law, the system allowed officials to reject marriages that were found to be forced, such as human trafficking, children and infants, and those forced by patriarchs. The couple who married would be the only authorized party to register. The system would help build a new expectation for Marriages, by allowing citizens to play a role in setting healthy standards and helping to build a new society that would be very different from the past.[8]

Impact

China's divorce rate, though lower than in the Western countries, is increasing. Chinese women also have increased financial importance in the household.[9] There is historical debate over the effectiveness of the New Marriage Law in terms of the state's commitment to the policy, and therefore its success.[10]

Second Marriage Law

The New Marriage Law was updated in 1980 by the Second Marriage Law, which liberalized divorce,[11] bolstered the one-child policy, and instructed the courts to favor the interests of women and children in property distribution in divorce.

Article 28 of the 1980 Marriage Law also formalizes duties from younger generations to older, and from older generations to younger:[12]

Grandparents or maternal grandparents who can afford it shall have the duty to bring up their grandchildren who are minors and whose parents are dead or have no capacity of bringing them up. Grandchildren or maternal grandchildren who can afford it shall have the duty to support their grandparents or maternal grandparents whose children are dead or have no means to support them.

The let-out clauses in the law ("who can afford it") are applied generously.[12] By applying equally to "grandparents or maternal grandparents," the law also formalizes the rejection of the traditional preference for the paternal grandmother.[12] That traditional cultural preference had disintegrated following the Communist success in the Chinese civil war.[12]

Further updates in 1983 formalized the legal procedure for marriages between Chinese citizens and foreign nationals.[2] The Second Marriage Law was also amended in 2001 to outlaw married persons' cohabitation with a third party, aimed at curbing a resurgence of concubinage in big cities.[11]

See also

References

- "中华人民共和国民法典_滚动新闻_中国政府网". 2020-09-07. Archived from the original on 2020-09-07. Retrieved 2021-11-04.

- Chen, Xinxin (March 2001). "Marriage Law Revisions Reflect Social Progress in China". China Today. Archived from the original on 2010-06-29. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- Mao, Zedong (1 January 1992). The Writings of Mao Zedong, 1949-1976: January 1956-December 1957. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780873323925 – via Google Books.

- Hughes, Sarah; Hughes, Brady (1997). Women in World History: Readings from 1500 to the present. M.E. Sharpe. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-56324-313-4.

- Niida, Noboro (June 2010). "Land Reform and New Marriage Law in China" (PDF). The Developing Economies. Wiley-Blackwell. 48 (2): B5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-03.

- Hershatter, Gail (2010). The Gender of Memory: Rural Women in China's Collective Past. University of California Press. p. 109.

- Hershatter, Gail (2010). The Gender of Memory: Rural Women in China's Collective Past. University of California Press. pp. 110–113.

- NIIDA, N. (1964), LAND REFORM AND NEW MARRIAGE LAW IN CHINA. The Developing Economies, p. 6-10

- Wan, Elaine Y. (1998-09-10). "China's Divorce Problem". Vol. 118, no. 57. The Tech. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- Hershatter, Gail (2010). The Gender of Memory: Rural Women in China's Collective Past. University of California Press. pp. 96–129.

- Wen, Chihua (2010-08-04). "For love or money". China Daily. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

- Lary, Diana (2022). China's grandmothers : gender, family, and aging from late Qing to twenty-first century. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-009-06478-1. OCLC 1292532755.