TrES-2b

TrES-2b (Kepler-1b) is an extrasolar planet orbiting the star GSC 03549-02811 located 750 light years away from the Solar System. The planet was identified in 2011 as the darkest known exoplanet, reflecting less than 1% of any light that hits it. Reflecting less light than charcoal, on the surface the planet is said to be pitch black.[4] The planet's mass and radius indicate that it is a gas giant with a bulk composition similar to that of Jupiter. Unlike Jupiter, but similar to many planets detected around other stars, TrES-2b is located very close to its star and belongs to the class of planets known as hot Jupiters. This system was within the field of view of the Kepler spacecraft.[1]

Size comparison of TrES-2b with Jupiter

tres-2B | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | O'Donovan et al. |

| Discovery site | California & Arizona, USA |

| Discovery date | August 21, 2006 confirmed September 8, 2006 |

| Transit | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 0.03556±0.00075 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0 |

| 2.47063±0.00001 d | |

| Inclination | 83.62±0.14[2] |

| Star | GSC 03549-02811 A[2] |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | 1.272±0.041[2] RJ |

| Mass | 1.199±0.052[2] MJ |

| 3.284±0.016[2] g | |

| Albedo | 0.0136 |

| Temperature | 1885+51 −66 K.[3] |

This planet continues to be studied by other projects, and the parameters are continuously improving. A 2007 study improved stellar and planetary parameters.[5] A 2008 study concluded that the TrES-2 system is a binary star system. This significantly affects the values for the stellar and the planetary parameters.[2]

Discovery

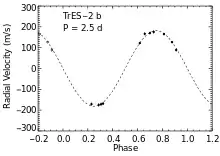

TrES-2b was discovered on August 21, 2006 by the Trans-Atlantic Exoplanet Survey (TrES) by detecting the transit of the planet across its parent star using Sleuth (Palomar Observatory, California) and PSST (Lowell Observatory, Arizona), part of the TrES network of 10–cm telescopes. The discovery was confirmed by the W. M. Keck Observatory on September 8, 2006, by measuring the radial velocity of the star that hosts TrES-2b.[1]

Spin-orbit angle

In August 2008 more details of the relationship between the parent star and the orbit of the planet were published. The orbit was determined to be tilted by −9±12° from the stellar equator. The orbital direction was determined to be in the same direction as the star's rotation (prograde).[6]

Kepler mission

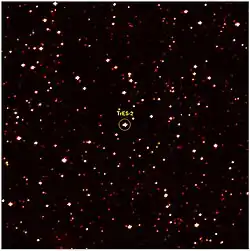

NASA launched Kepler in March 2009. The spacecraft is dedicated to the discovery of extrasolar planets by the transit method from solar orbit. In April 2009 the project released the first light images from the spacecraft, and TrES-2b was one of two objects highlighted in these images. Although TrES-2b is not the only known exoplanet in the field of view of this spacecraft it is the only one identified in the first light images. This object is important for calibration and check-out.[7]

The Kepler mission also managed to detect the mass of the planet from Kepler data alone through the analysis of the light curve of the host star. In addition to detecting the planet directly, the planet was also detected by analysis of the star brightness caused by the gravitational tug of TrES-2b by shape distortion of the host star and by light variations due to Doppler beaming.[8]

Albedo

The first important result from the Kepler Mission about TrES-2b is an extremely low geometric albedo measured in 2011, making it the darkest known exoplanet.[4] If the entire day–night contrast were due to geometric albedo, it would be 2.53%, but modeling suggests that much of this is dayside emission and the true albedo is much lower. It is estimated to be less than 1% and for best-fit model it is about 0.04%. This makes TrES-2b the darkest known exoplanet, reflecting less light than coal or black acrylic paint.[9] It is not clear why the planet is so dark. One reason could be an absence of reflective clouds such as those which make Jupiter so bright, due to TrES-2b's proximity to its parent star and the consequent high temperature. Another reason could be the presence in the atmosphere of light-absorbing chemicals such as vaporized sodium, potassium, or gaseous titanium oxide;[10] however, Kipping and Spiegel excluded heavy oxides of titanium and vanadium from their models, as it seems unrealistic that condensed, heavy compounds be present in the upper atmosphere. They also note that in general, hot Jupiters are expected to be dark, because "absorption due to the broad wings of the sodium and potassium D lines is thought to dominate their visible spectra", and, apart from that of Kepler-7b (38±12%), albedo measurements for hot Jupiters have generally given only upper limits.[4]

References

- O'Donovan, Francis T.; et al. (2006). "TrES-2: The First Transiting Planet in the Kepler Field". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 651 (1): L61–L64. arXiv:astro-ph/0609335. Bibcode:2006ApJ...651L..61O. doi:10.1086/509123.

- Daemgen, S.; Hormuth, F.; Brandner, W.; Bergfors, C.; Janson, M.; Hippler, S.; Henning, T. (2009). "Binarity of transit host stars — Implications for planetary parameters" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 498 (2): 567–574. arXiv:0902.2179. Bibcode:2009A&A...498..567D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200810988. S2CID 9893376.

- A Comprehensive Study of Kepler Phase Curves and Secondary Eclipses:Temperatures and Albedos of Confirmed Kepler Giant Planets

- David M. Kipping & David S. Spiegel (2011). "Detection of visible light from the darkest world" (PDF). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 417 (1): L88. arXiv:1108.2297. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.417L..88K. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2011.01127.x. S2CID 119287494. Archived from the original on March 17, 2012. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Alessandro Sozzetti; Torres, Guillermo; Charbonneau, David; Latham, David W.; Holman, Matthew J.; Winn, Joshua N.; Laird, John B.; o’Donovan, Francis T. (August 1, 2007). "Improving Stellar and Planetary Parameters of Transiting Planet Systems: The Case of TrES-2". The Astrophysical Journal. 664 (2): 1190–1198. arXiv:0704.2938. Bibcode:2007ApJ...664.1190S. doi:10.1086/519214. S2CID 17078552.

- Winn, Joshua N.; Johnson, John Asher; Narita, Norio; Suto, Yasushi; Turner, Edwin L.; Fischer, Debra A.; Butler, R. Paul; Vogt, Steven S.; et al. (2008). "The Prograde Orbit of Exoplanet TrES-2b". The Astrophysical Journal. 682 (2): 1283–1288. arXiv:0804.2259. Bibcode:2008ApJ...682.1283W. doi:10.1086/589235. S2CID 14857922.

- "Kepler Eyes Cluster and Known Planet". NASA. 2009-04-16. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- Photometrically derived masses and radii of the planet and star in the TrES-2 system: Thomas Barclay, Daniel Huber, Jason F. Rowe, Jonathan J. Fortney, Caroline V. Morley, Elisa V. Quintana, Daniel C. Fabrycky, Geert Barentsen, Steven Bloemen, Jessie L. Christiansen, Brice-Olivier Demory, Benjamin J. Fulton, Jon M. Jenkins, Fergal Mullally, Darin Ragozzine, Shaun E. Seader, Avi Shporer, Peter Tenenbaum, Susan E. Thompson

- Charles Q. Choi (2011-08-11). "Coal-Black Alien Planet Is Darkest Ever Seen". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-24. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- Baldwin, Emily (2011-08-11). "Exoplanet blacker than coal". Astronomy Now. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

External links

- Host to 'Hot Jupiter' (labeled) NASA, 2009-04-16

- TrES-2: Most Massive Nearby Transiting Exoplanet

- Jupiter-Sized Transiting Planet Found by Astronomers Using Novel Telescope Network

- Light curve for TrES-2b using differential photometry