Wars of the Diadochi

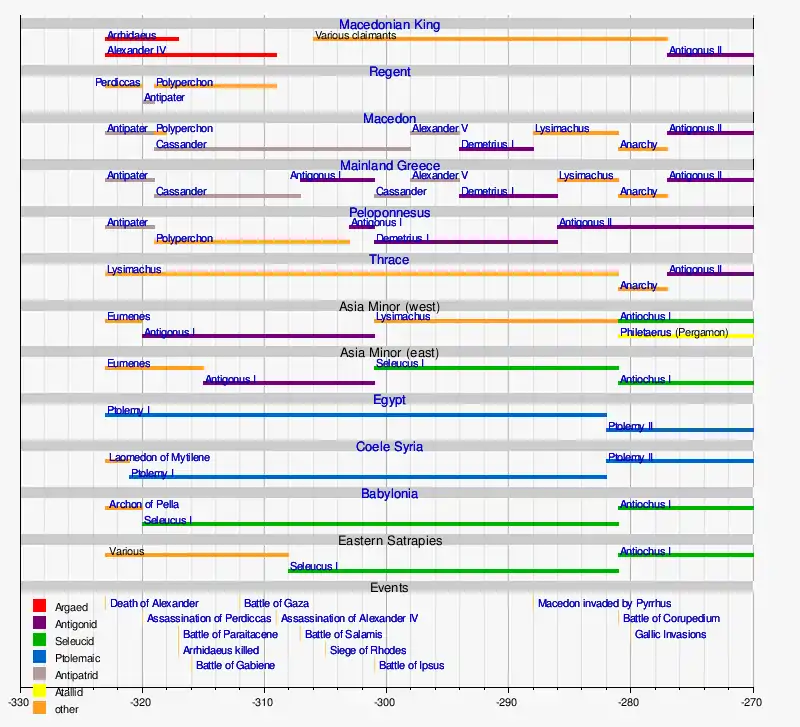

The Wars of the Diadochi (Ancient Greek: Πόλεμοι τῶν Διαδόχων, Pólemoi tōn Diadóchōn), or Wars of Alexander's Successors, were a series of conflicts that were fought between the generals of Alexander the Great, known as the Diadochi, over who would rule his empire following his death. The fighting occurred between 322 and 281 BC.

| Wars of Diadochi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The various kingdoms of the Diadochi c. 301 BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| First War (321–319 BC): |

First War (321–319 BC):

| ||||||

| Second War (318–316 BC): |

Second War (318–316 BC):

| ||||||

| Third War (315-311BC): | Third War (315-311 BC): | ||||||

| Babylon War (311–309 BC): | Babylon War (311–309 BC): | ||||||

| Fourth War (307–301 BC): | Fourth War (307–301 BC): | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| First War (321–319 BC): | First War (321–319 BC): | ||||||

| Second War 318–316 BC): | Second War (318–316 BC): | ||||||

| Third War (315–311 BC): | Third War (315–311 BC): | ||||||

| Babylon War (311–309 BC): | Babylon War (311–309 BC): | ||||||

| Fourth War (307–301 BC): | Fourth War (308–301 BC): | ||||||

Background

Alexander the Great died on June 10, 323 BC, leaving behind an empire that stretched from Macedon and the rest of Greece in Europe to the Indus valley in South Asia. The empire had no clear successor, with the Argead family, at this point, consisting of Alexander's mentally disabled half-brother, Arrhidaeus; his unborn son Alexander IV; his reputed illegitimate son Heracles; his mother Olympias; his sister Cleopatra; and his half-sisters Thessalonike and Cynane.[1]

Alexander's death was the catalyst for the disagreements that ensued between his former generals resulting in a succession crisis. Two main factions formed after the death of Alexander. The first of these was led by Meleager, who supported the candidacy of Alexander's half-brother, Arrhidaeus. The second was led by Perdiccas, the leading cavalry commander, who believed it would be best to wait until the birth of Alexander's unborn child, by Roxana. Both parties agreed to a compromise, wherein Arrhidaeus would become king as Philip III and rule jointly with Roxana's child, providing it was a male heir. Perdiccas was designated as regent of the empire, with Meleager acting as his lieutenant. However, soon after, Perdiccas had Meleager and the other leaders who had opposed him murdered, and he assumed full control.

The generals who had supported Perdiccas were rewarded in the partition of Babylon by becoming satraps of the various parts of the empire. Ptolemy received Egypt; Laomedon received Syria and Phoenicia; Philotas took Cilicia; Peithon took Media; Antigonus received Phrygia, Lycia and Pamphylia; Asander received Caria; Menander received Lydia; Lysimachus received Thrace; Leonnatus received Hellespontine Phrygia; and Neoptolemus had Armenia. Macedon and the rest of Greece were to be under the joint rule of Antipater, who had governed them for Alexander, and Craterus, a lieutenant of Alexander. Alexander's secretary, Eumenes of Cardia, was to receive Cappadocia and Paphlagonia.

In the east, Perdiccas largely left Alexander's arrangements intact – Taxiles and Porus ruled over their kingdoms in India; Alexander's father-in-law Oxyartes ruled Gandara; Sibyrtius ruled Arachosia and Gedrosia; Stasanor ruled Aria and Drangiana; Philip ruled Bactria and Sogdiana; Phrataphernes ruled Parthia and Hyrcania; Peucestas governed Persis; Tlepolemus had charge over Carmania; Atropates governed northern Media; Archon got Babylonia; and, Arcesilas ruled northern Mesopotamia.

Lamian War

The news of Alexander's death inspired a revolt in Greece, known as the Lamian War. Athens and other cities formed a coalition and besieged Antipater in the fortress of Lamia, however, Antipater was relieved by a force sent by Leonnatus, who was killed in battle. The Athenians were defeated at the Battle of Crannon on September 5, 322 BC by Craterus and his fleet.

At this time, Peithon suppressed a revolt of Greek settlers in the eastern parts of the empire, and Perdiccas and Eumenes subdued Cappadocia.

First War of the Diadochi, 321–319 BC

Perdiccas, who was already betrothed to the daughter of Antipater, attempted to marry Alexander's sister, Cleopatra, a marriage which would have given him claim to the Macedonian throne. In 322 BC, Antipater, Craterus and Antigonus all formed a coalition against Perdiccas's growing power. Soon after, Antipater would send his army, under the command of Craterus, into Asia Minor. In late 322 or early 321 BC, Ptolemy stole Alexander's body on its way to Macedonia and then joined the coalition. A force under Eumenes defeated Craterus at the battle of the Hellespont, however, Perdiccas was soon after murdered by his own generals Peithon, Seleucus, and Antigenes during his invasion of Egypt, after a failed attempt to cross the Nile.[2]

Ptolemy came to terms with Perdiccas' murderers, making Peithon and Arrhidaeus regents in Perdiccas's place, but soon these came to a new agreement with Antipater at the Treaty of Triparadisus. Antipater was made Regent of the Empire, and the two kings were moved to Macedon. Antigonus was made Strategos of Asia and remained in charge of Phrygia, Lycia, and Pamphylia, to which was added Lycaonia. Ptolemy retained Egypt, Lysimachus retained Thrace, while the three murderers of Perdiccas—Seleucus, Peithon, and Antigenes—were given the provinces of Babylonia, Media, and Susiana respectively. Arrhidaeus, the former regent, received Hellespontine Phrygia. Antigonus was charged with the task of rooting out Perdiccas's former supporter, Eumenes. In effect, Antipater retained for himself control of Europe, while Antigonus, as Strategos of the East, held a similar position in Asia.[3]

Although the First War ended with the death of Perdiccas, his cause lived on. Eumenes was still at large with a victorious army in Asia Minor. So were Alcetas, Attalus, Dokimos and Polemon who had also gathered their armies in Asia Minor. In 319 BC Antigonus, after receiving reinforcements from Antipater's European army, first campaigned against Eumenes (see: battle of Orkynia), then against the combined forces of Alcetas, Attalus, Dokimos and Polemon (see: battle of Cretopolis), defeating them all.

Second War of the Diadochi, 318–316 BC

Another war soon broke out between the Diadochi. At the start of 318 BC Arrhidaios, the governor of Hellespontine Phrygia, tried to take the city of Cyzicus.[4] Antigonus, as the Strategos of Asia, took this as a challenge to his authority and recalled his army from their winter quarters. He sent an army against Arrhidaios while he himself marched with the main army into Lydia against its governor Cleitus whom he drove out of his province.[5]

Cleitus fled to Macedon and joined Polyperchon, the new Regent of the Empire, who decided to march his army south to force the Greek cities to side with him against Cassander and Antigonus. Cassander, reinforced with troops and a fleet by Antigonus, sailed to Athens and thwarted Polyperchon's efforts to take the city.[6] From Athens Polyperchon marched on Megalopolis which had sided with Cassander and besieged the city. The siege failed and he had to retreat losing a lot of prestige and most of the Greek cities.[7] Eventually Polyperchon retreated to Epirus with the infant King Alexander IV. There he joined forces with Alexander's mother Olympias and was able to re-invade Macedon. King Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander's half-brother, having defected to Cassander's side at the prompting of his wife, Eurydice, was forced to flee, only to be captured in Amphipolis, resulting in the execution of himself and the forced suicide of his wife, both purportedly at the instigation of Olympias. Cassander rallied once more, and seized Macedon. Olympias was murdered, and Cassander gained control of the infant King and his mother. Eventually, Cassander became the dominant power in the European part of the Empire, ruling over Macedon and large parts of Greece.

Meanwhile, Eumenes, who had gathered a small army in Cappadocia, had entered the coalition of Polyperchon and Olympias. He took his army to the royal treasury at Kyinda in Cilicia where he used its funds to recruit mercenaries. He also secured the loyalty of 6,000 of Alexander's veterans, the Argyraspides (the Silver Shields) and the Hypaspists, who were stationed in Cilicia.[8] In the spring of 317 BC he marched his army to Phoenica and began to raise a naval force on the behalf of Polyperchon.[9] Antigonus had spent the rest of 318 BC consolidating his position and gathering a fleet. He now used this fleet (under the command of Nicanor who had returned from Athens) against Polyperchon's fleet in the Hellespont. In a two-day battle near Byzantium, Nicanor and Antigonus destroyed Polyperchon's fleet.[10] Then, after settling his affairs in western Asia Minor, Antigonus marched against Eumenes at the head of a great army. Eumenes hurried out of Phoenicia and marched his army east to gather support in the eastern provinces.[11] In this he was successful, because most of the eastern satraps joined his cause (when he arrived in Susiana) more than doubling his army.[12] They marched and counter-marched throughout Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Susiana and Media until they faced each other on a plain in the country of the Paraitakene in southern Media. There they fought a great battle −the battle of Paraitakene− which ended inconclusively.[13] The next year (315) they fought another great but inconclusive battle −the battle of Gabiene− during which some of Antigonus's troops plundered the enemy camp.[14] Using this plunder as a bargaining tool, Antigonus bribed the Argyraspides who arrested and handed over Eumenes.[15] Antigonus had Eumenes and a couple of his officers executed.[15] With Eumenes's death, the war in the eastern part of the Empire ended.

Antigonus and Cassander had won the war. Antigonus now controlled Asia Minor and the eastern provinces, Cassander controlled Macedon and large parts of Greece, Lysimachus controlled Thrace, and Ptolemy controlled Egypt, Syria, Cyrene and Cyprus. Their enemies were either dead or seriously reduced in power and influence.

Third War of the Diadochi, 315–311 BC

Though his authority had seemed secure with his victory over Eumenes, the eastern dynasts were unwilling to see Antigonus rule all of Asia.[16] In 314 BC they demanded from Antigonus that he cede Lycia and Cappadocia to Cassander, Hellespontine Phrygia to Lysimachus, all of Syria to Ptolemy, and Babylonia to Seleucus, and that he share the treasures he had captured.[17] Antigonus only answer was to advise them to be ready, then, for war.[18] In this war, Antigonus faced an alliance of Ptolemy (with Seleucus serving him), Lysimachus, and Cassander. At the start of the campaigning season of 314 BC Antigonus invaded Syria and Phoenicia, which were under Ptolemy's control, and besieged Tyre.[19] Cassander and Ptolemy started supporting Asander (satrap of Caria) against Antigonus who ruled the neighbouring provinces of Lycia, Lydia and Greater Phrygia. Antigonus then sent Aristodemus with 1,000 talents to the Peloponnese to raise a mercenary army to fight Cassander,[20] he allied himself to Polyperchon, who still controlled parts of the Peloponnese, and he proclaimed freedom for the Greeks to get them on their side. He also sent his nephew Ptolemaios with an army through Cappadocia to the Hellespont to cut Asander off from Lysimachus and Cassander. Polemaios was successful, securing the northwest of Asia Minor for Antigonus, even invading Ionia/Lydia and bottling up Asander in Caria, but he was unable to drive his opponent from his satrapy.

Eventually Antigonus decided to campaign against Asander himself, leaving his oldest son Demetrius to protect Syria and Phoenica against Ptolemy. Ptolemy and Seleucus invaded from Egypt and defeated Demetrius in the Battle of Gaza. After the battle, Seleucus went east and secured control of Babylon (his old satrapy), and then went on to secure the eastern satrapies of Alexander's empire. Antigonus, having defeated Asander, sent his nephews Telesphorus and Polemaios to Greece to fight Cassander, he himself returned to Syria/Phoenica, drove off Ptolemy, and sent Demetrius east to take care of Seleucus. Although Antigonus now concluded a compromise peace with Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Cassander, he continued the war with Seleucus, attempting to recover control of the eastern reaches of the empire. Although he went east himself in 310 BC, he was unable to defeat Seleucus (he even lost a battle to Seleucus) and had to give up the eastern satrapies.

At about the same time, Cassander had young King Alexander IV and his mother Roxane murdered, ending the Argead dynasty, which had ruled Macedon for several centuries. As Cassander did not publicly announce the deaths, all of the various generals continued to recognize the dead Alexander as king, however, it was clear that at some point, one or all of them would claim the kingship. At the end of the war there were five Diadochi left: Cassander ruling Macedon and Thessaly, Lysimachus ruling Thrace, Antigonus ruling Asia Minor, Syria and Phoenicia, Seleucus ruling the eastern provinces and Ptolemy ruling Egypt and Cyprus. Each of them ruled as kings (in all but name).

Babylonian War, 311–309 BC

The Babylonian War was a conflict fought between 311 and 309 BC between the Diadochi kings Antigonus I Monophthalmus and Seleucus I Nicator, ending in a victory for the latter, Seleucus I Nicator. The conflict ended any possibility of restoration of the empire of Alexander the Great, a result confirmed in the Battle of Ipsus.

Fourth War of the Diadochi, 307–301 BC

Ptolemy had been expanding his power into the Aegean and to Cyprus, while Seleucus went on a tour of the east to consolidate his control of the vast eastern territories of Alexander's empire. Antigonus resumed the war, sending his son Demetrius to regain control of Greece. In 307 he took Athens, expelling Demetrius of Phaleron, Cassander's governor, and proclaiming the city free again. Demetrius now turned his attention to Ptolemy, invading Cyprus and defeating Ptolemy's fleet at the Battle of Salamis. In the aftermath of this victory, Antigonus and Demetrius both assumed the crown, and they were shortly followed by Ptolemy, Seleucus, Lysimachus, and eventually Cassander.

In 306, Antigonus attempted to invade Egypt, but storms prevented Demetrius' fleet from supplying him, and he was forced to return home. Now, with Cassander and Ptolemy both weakened, and Seleucus still occupied in the East, Antigonus and Demetrius turned their attention to Rhodes, which was besieged by Demetrius's forces in 305 BC. The island was reinforced by troops from Ptolemy, Lysimachus, and Cassander. Ultimately, the Rhodians reached a compromise with Demetrius – they would support Antigonus and Demetrius against all enemies, save their great ally Ptolemy. Ptolemy took the title of Soter ("Savior") for his role in preventing the fall of Rhodes, but the victory was ultimately Demetrius's, as it left him with a free hand to attack Cassander in Greece.

At the beginning of 304, Cassander managed to capture Salamis and besieged Athens.[21] Athens petitioned Antigonus and Demetrius to come to their aid.[21] Demetrius gathered a large fleet and landed his army in Boeotia in the rear of Cassander's forces. He freed the cities of Chalkis and Eretria, renewed the alliance with the Boeotian League and the Aetolian League, raised the siege of Athens and drove Cassander's forces from central Greece.[22] In the spring of 303, Demetrius marched his army into the Peloponnese and took the cities of Sicyon and Corinth, he then campaigned in Argolis, Achaea and Arcadia, bringing the northern and central Peloponnese into the Antigonid camp.[23] In 303–302 Demetrius formed a new Hellenic League, the League of Corinth, with himself and his father as presidents, to "defend" the Greek cities against all enemies (and particularly Cassander).

In the face of these catastrophes, Cassander sued for peace, but Antigonus rejected the claims, and Demetrius invaded Thessaly, where he and Cassander battled in inconclusive engagements. But now Cassander called in aid from his allies, and Anatolia was invaded by Lysimachus, forcing Demetrius to leave Thessaly and send his armies to Asia Minor to assist his father. With assistance from Cassander, Lysimachus overran much of western Anatolia, but was soon (301 BC) isolated by Antigonus and Demetrius near Ipsus. Here came the decisive intervention from Seleucus, who arrived in time to save Lysimachus from disaster and utterly crush Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus. Antigonus was killed in the fight, and Demetrius fled back to Greece to attempt to preserve the remnants of his rule there. Lysimachus and Seleucus divided up Antigonus's Asian territories between them, with Lysimachus receiving western Asia Minor and Seleucus the rest, except Cilicia and Lycia, which went to Cassander's brother Pleistarchus.

The struggle over Macedon, 298–285 BC

The events of the next decade and a half were centered around various intrigues for control of Macedon itself. Cassander died in 298 BC, and his sons, Antipater and Alexander, proved weak kings. After quarreling with his older brother, Alexander V called in Demetrius, who had retained control of Cyprus, the Peloponnese, and many of the Aegean islands, and had quickly seized control of Cilicia and Lycia from Cassander's brother, as well as Pyrrhus, the King of Epirus. After Pyrrhus had intervened to seize the border region of Ambracia, Demetrius invaded, killed Alexander, and seized control of Macedon for himself (294 BC). While Demetrius consolidated his control of mainland Greece, his outlying territories were invaded and captured by Lysimachus (who recovered western Anatolia), Seleucus (who took most of Cilicia), and Ptolemy (who recovered Cyprus, eastern Cilicia, and Lycia).

Soon, Demetrius was forced from Macedon by a rebellion supported by the alliance of Lysimachus and Pyrrhus, who divided the Kingdom between them, and, leaving Greece to the control of his son, Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius launched an invasion of the east in 287 BC. Although initially successful, Demetrius was ultimately captured by Seleucus (286 BC), drinking himself to death two years later.

The struggle of Lysimachus and Seleucus, 285–281 BC

Although Lysimachus and Pyrrhus had cooperated in driving Antigonus Gonatas from Thessaly and Athens, in the wake of Demetrius's capture they soon fell out, with Lysimachus driving Pyrrhus from his share of Macedon. Dynastic struggles also rent Egypt, where Ptolemy decided to make his younger son Ptolemy Philadelphus his heir rather than the elder, Ptolemy Ceraunus. Ceraunus fled to Seleucus. The eldest Ptolemy died peacefully in his bed in 282 BC, and Philadelphus succeeded him.

In 282 BC Lysimachus had his son Agathocles murdered, possibly at the behest of his second wife, Arsinoe II. Agathocles's widow, Lysandra, fled to Seleucus, who after appointing his son Antiochus ruler of his Asian territories, defeated and killed Lysimachus at the Battle of Corupedium in Lydia in 281 BC. Selucus hoped to take control of Lysimachus' European territories, and in 281 BC, soon after arriving in Thrace, he was assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus, for reasons that remain unclear.

The Gallic invasions and consolidation, 280–275 BC

Ptolemy Ceraunus did not rule Macedon for very long. The death of Lysimachus had left the Danube border of the Macedonian kingdom open to barbarian invasions, and soon tribes of Gauls were rampaging through Macedon and Greece, and invading Asia Minor. Ptolemy Ceraunus was killed by the invaders, and after several years of chaos, Demetrius's son Antigonus Gonatas emerged as ruler of Macedon. In Asia, Seleucus's son, Antiochus I, also managed to defeat the Celtic invaders, who settled down in central Anatolia in the part of eastern Phrygia that would henceforward be known as Galatia after them.

Now, almost fifty years after Alexander's death, some sort of order was restored. Ptolemy ruled over Egypt, southern Syria (known as Coele-Syria), and various territories on the southern coast of Asia Minor. Antiochus ruled the Asian territories of the empire, while Macedon and Greece (with the exception of the Aetolian League) fell to Antigonus.

Aftermath

References

- Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State, pp.49–50.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 33,1–36,5.; Arrian, Anabasis, 1,28; Cornelius Nepos, Parallel Lives, Eumenes 5,1.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica XVIII 39,1–39,6; Arrian, Anabasis, 1,34–37.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 51,1–7.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica,XVIII 52,5–8.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 64,1–68,1.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 68,2–72,1.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 59,1–3.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 63,6.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 72,3–4.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 73,1–2.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 15,1–2.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 26,1–31,5.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 40,1–43,8; Plutarch, Parallel Lives, Eumenes 16,3–17,1; Polyainos, Strategemata IV 6,13.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica XIX 43,8–44,3; Plutarch, Parallel Lives Eumenes 17,1–19,1; Cornelius Nepos, Parallel Lives, Eumenes 10,3–13,1.

- Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State, p.108.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 57,1.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 57,2; Appian, Syriaka 53.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 57,4.

- Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State, p.113.

- Plut. Dem. 23,1.

- Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed, p. 169.

- Diod. XX, 102–104.

- Shipley, Graham (2000) The Greek World After Alexander. Routledge History of the Ancient World. (Routledge, New York)

- Walbank, F. W. (1984) The Hellenistic World, The Cambridge Ancient History, volume VII. part I. (Cambridge)

- Waterfield, Robin (2011). Dividing the Spoils – The War for Alexander the Great's Empire (hardback). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 273 pages. ISBN 978-0-19-957392-9.

External links

- Alexander's successors: the Diadochi from Livius.org (Jona Lendering)

- Wiki Classical Dictionary: "Successors" category and Diadochi entry

- T. Boiy, "Dating Methods During the Early Hellenistic Period", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Vol. 52, 2000 PDF format. A recent study of primary sources for the chronology of eastern rulers during the period of the Diadochi.