The Gardener (painting)

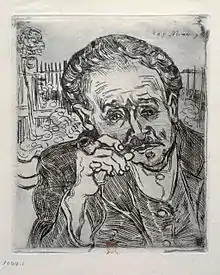

The Gardener, also known as Portrait of a Young Peasant or Provençal Peasant, is an oil-on-canvas painting by Vincent van Gogh, dated of September 1889 and held in the National Gallery of Modern Art, in Rome.[2]

| The Gardener | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh |

| Year | 1889[1] |

| Type | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 61 cm × 50 cm (24 in × 20 in) |

| Location | Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome |

The painting, considered the most important by the Dutch painter among those in Italian public collections, is a masterpiece of Van Gogh's Provençal period[3] and shows some of the fundamental themes of his painting, such as the use of the portrait, the relationship with nature and the combination of primary and complementary colors.

Title and cataloging of the work

Van Gogh, unusually, does not mention The Gardener in any of his letters[4] and therefore does not give it any title.[5] In any case, the canvas has always belonged to the catalog raisonné of Van Gogh's works. It first appeared in the catalog drawn up in 1928—revised in 1970—by Jacob-Baart de la Faille, entitled "The work of Vincent Van Gogh", which numbered the painting as 531. It was then included in the catalog "The complete van Gogh" (1980) by Jan Hulsker, who gave The Gardener the number 1779. In order to differentiate between the two cataloging systems, the critics associate the initials of the authors of the catalogs with the numbers of the different paintings. Therefore, The Gardener is, respectively, F531 and JH1779, depending on the cataloging system referred to.[2][6] In the collection of the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome, the canvas is cataloged under inventory number 8638.[4]

Although the work is often known by the title The Gardener, this is in fact a fairly recent title, which does not fully express the theme or message of the work.[4] It is a title probably inspired by the background of the painting which, rather than recalling a cultivated field, resembles a garden. Instead, other hypotheses hold that the title derives from the possibility that it is the portrait of the gardener of the psychiatric hospital of Saint Rémy, where Vincent van Gogh was a patient between April 1889 and May 1890.[7][8]

Van Gogh's friend Émile Bernard, in his letters written in 1911, gave it the title Paysan provençal (English: Provençal peasant),[4] while at the first exhibition of the impressionists, organized at the Lyceum in Florence in 1910, it was presented as Peasant's head.[3] More generally, in the cataloging of Van Gogh's works it is identified as Peasant or as Portrait of a Young Peasant,[2][4] while in the collection of the Roman museum the title The Gardener (Provençal Peasant) has prevailed.[4]

History

Van Gogh painted the canvas in September 1889 while residing at the hospital in Saint Rémy.[2] The dating of the month of execution is approximate—although today almost all critics accept it as valid—because Van Gogh does not mention the work in the numerous letters he wrote to his brother Theo and friends.[5]

At first, in fact, it was considered to be part of the body of work that Van Gogh painted in Arles, a period from February 1888 to March 1889. Subsequently, it was believed to be a work from the period spent in Saint Rémy (April 1889 – April 1890). Finally, Hulsker's studies placed the work in September 1889, a period when the painter was being treated at the Saint Paul de Mausole hospital in Saint Rémy, linking it to the painter's strong interest in portraits during that period.[3] In early September, Van Gogh, after a serious nervous breakdown and a period of inactivity, returned to painting with great commitment[4] and he wrote to his brother Theo:[9]

My desire to make portraits these days is terribly strong.

After the painter's death, the work entered the collectors' market until it reached the Parisian gallery of Paul Rosemberg, where it was bought in 1910 by Gustavo Sforni, intellectual and macchiaioli painter who in the early 20th century brought to Florence, the city where he lived, several works of art of modern painting: among them were the Portrait of Monsieur Chocquet (1889)[10] by Paul Cézanne, two oil paintings by Maurice Utrillo and a pastel painting by Edgar Degas.[1] After its arrival in Italy, The Gardener was loaned for the Italian exhibition dedicated to the impressionists organized by the writer and painter Ardengo Soffici between April and May 1910 in the halls of the Lyceum Club in Florence.[11] The exhibition bore the name "Prima mostra italiana dell'impressionismo".[11] The canvas, exhibited under number 71,[1] was presented alongside works by Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Jean-Louis Forain, Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and eighteen sculptures by Medardo Rosso.[12][11] That same year, Soffici gave a not very positive opinion on The Gardener, since in Van Gogh's work he observed a break with the lessons of Cézanne, an artist he held in high esteem:[1]

There is no lack of virtues... (but when it emerges, it fails). The reason when perhaps the maturity of the years would have led him to a simpler understanding of nature... instead of a sincere artist's nature, a twisted will, struggling with a rebellious and undefeated matter.

After the temporary exhibition, the work returned to the hands of its owner, Sforni. The latter, after the criticism of the Florence exhibition, thought that his contemporaries would criticize the work if he put it on display in Italy, so he jealously guarded it in his own home, allowing it to be seen only by his friends and intellectuals who, like him, were attentive to the new foreign trends and the innovations of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.[3][1]

After the death of the collector in 1940, his lawyer uncle Giovanni Verusio inherited the painting along with his entire collection which, in addition to the aforementioned French authors, included the works of Fattori—more than forty in total, including oil paintings and drawings—Signorini and Severini.[13] Although Van Gogh had not yet reached the popularity that the art market brought him in the 1980s, the painting was already recognized as the most precious and valuable piece in that collection, so that during the end of World War II Verusio, who had taken refuge in a farmhouse in the Tuscan countryside, hid it in a wooden box under the straw of a lemon tree greenhouse in Pian dei Giullari to protect it from looting by German soldiers.[13]

After the war, in 1945, it was exhibited at the Pitti Palace, in the exhibition of French painting organized by Berenson entitled "La peinture française à Florence".[3] It was also exhibited in 1952, in the retrospective exhibition organized by Lamberto Vitali at the Royal Palace in Milan with the title "Vincent Van Gogh".[3] The work began to gain importance in the national territory and in 1954 the Italian State declared the painting a work of historical and artistic interest.

In 1966, the lawyer's wife, Sandra Verusio, brought the canvas to safety during the flood of florence by taking it to Rome.[13] There the canvas remained in the dining room of the house for about ten years—though often replaced by a copy. The possession of the painting allowed the family to enter the salons of high society and to interact with the great personalities of their time thanks to the numerous requests that the Verusio couple received to be able to admire the Van Gogh. Figures of the artistic world such as Renato Guttuso and the art critic Giuliano Briganti passed by, as well as other important personalities from different fields: for example, the lawyer Agnelli came to the Verusio family home on several occasions to admire the canvas.[14][15] The painting's fame, however, inevitably led to several theft attempts. Mrs. Verusio, speaking of the thieves, said in 1998 during an interview:[13]

They have come five times to take it away but never succeeded. They settled for furs and silver. However, that painting had become a problem. During the vacations I would take it to the bank with the Cinquecento, accompanied only by an old houseboy; such recklessness!

Tired of this situation, the lawyer Verusio decided to sell the canvas, which was acquired in 1977 for the figure of 600 million liras, well below the price of the painting at the time, which was estimated at least 1.2 billion. It was bought by the Roman gallery owner Silvestro Pierangeli,[13] since the Italian State at that time did not exercise its right of pre-emption.[16] What actually happened is that Pietrangeli acted as an intermediary for an anonymous buyer, who, as it was discovered in 1983, was the Swiss gallery owner Ernst Beyeler.[16] The Italian State mobilized only in 1988, at the height of the impressionist collecting market, when Beyeler announced that he was going to sell the work to the Guggenheim Museum in Venice for the sum of fourteen billion lire. In that operation it was shown that during the first negotiation, Beyeler did not turn out to be the real buyer, since in the minutes of sale the name registered was that of Pierangeli.[17]

Thus, in 1989 the Italian State demanded to practice its right of pre-emption and repurchased the painting, reimbursing Beyeler the same amount he had paid in 1977: 600 million lire. Beyeler considered that the figure was too far below the market price—if the State had not repurchased the painting, the Guggenheim Museum would have paid it 25 times more—and sued the Italian State. After losing all the lawsuits initiated in Italy, he appealed to the European Court of European Rights in Strasbourg.[18] Meanwhile, in 1995, the painting was transferred to Rome and the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art, where it was placed next to the other Van Gogh painting owned by the Gallery, L'arlésienne (Madame Ginoux).[19]

In 2000, the European court ruled for the first time: it affirmed that the Italian State had a right of pre-emption but considered that it had exercised its right too late and had paid too low a price, so that it had enjoyed an "unjustified enrichment".[18] The trial on who should be the true owner of the work ended in May 2002, after more than a quarter of a century, when the judges of Strasbourg recognized the Italian State its legitimate possession and ownership of the work. Consequently, The Gardener officially and de jure entered the collection of the Roman museum. The judges awarded Beyeler a compensation of one million three hundred thousand euros plus fifty-five thousand euros reimbursement for the costs of the process.[17] Giuliano Urbani, the then Minister of Cultural Heritage, expressed his great satisfaction with regard to the sentence:[16]

The sentence issued by the judges of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, rejecting the request for the restitution of the famous canvas to the gallery owner Beyeler, has definitively closed a judicial episode that had been going on for years. Van Gogh's The Gardener, as the theft from the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome in May 1998 had already shown, remains in Italy and will serve to enrich the already rich state cultural heritage; a demonstration that, once again, the priority of the Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Activities is to protect and maintain the integrity of our artistic heritage.

Theft of the painting and subsequent recovery (1998)

Between the night of May 19 and 20, 1998, the painting earned a space on all the front pages of the newspapers because it was the object of a robbery at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome. In addition to The Gardener, the thieves took L'arlésienne (Madame Ginoux), also painted by Van Gogh in 1890, and Le Cabanon de Jourdan, a work by Paul Cézanne (1906).[20] The robbery was perpetrated by three armed, barefoot, balaclava-wearing thieves who waited inside the premises until the museum closed.[20]

The robbers bound, gagged and threatened the guards at gunpoint. The museum waiter noticed that the entrance was still open, so he alerted the carabinieri, who came and released the guards.[20] The theft had a strong media impact because of the fame of Van Gogh and Cézanne and the estimated value of the works; in such a way that it was compared to preceding thefts such as that of Caravaggio's Nativity, stolen in 1969 from the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo, and Gustav Klimt's Portrait of a Lady, stolen the previous year from the Ricci Oddi Modern Art Gallery in Piacenza[21] and recovered in 2019.[22]

Unlike the Palermo theft, that has not been recovered as of 2022, the three Rome canvases were recovered forty-six days later. Police arrested eight people for the theft.[21] The Italian-Belgian leader of the gang of thieves, Eneo Ximenes, commented upon being arrested:[21]

Congratulations, you did a good job, I'm screwed.

In the period between the theft and the recovery, the paintings had been taken to Turin to be sold to a buyer. The latter had backed out at the last moment because of the media tension that the event had raised and did not want to buy it despite a significant discount on the sale offered by the thieves, who had initially negotiated the operation with a price starting at fifteen to twenty billion lire.[21] Francesco Pellegrino reconstructed the theft of the works by Van Gogh and Cézanne in the volume Ore 22, furto in galleria, edited by Natyvi Contemporanea in 2013 and prefaced by Walter Veltroni, who was the Minister of Cultural Heritage at the time of the theft.

Description and style

The painting can be considered a masterpiece by the Dutch painter[1] and an exceptional example of his Provençal period portraits,[3] occupying a prominent place among the one hundred and forty paintings he produced while staying at the hospital of Saint Rémy.[23] Van Gogh painted it the year before his death, which occurred on July 27, 1890, at the height of his artistic maturity. To that same year—1889—belong other of his masterpieces such as Starry Night, Vase with Irises and his Self-Portraits. For this reason, it presents some important elements of his personal style.

The protagonist

The work is included in the series of numerous portraits that the painter made of the people around him. As he himself commented to his brother in a letter dated September 19, 1889:[24]

Whenever I have the chance, I work on portraits that sometimes I think are the most serious and best part of the rest of my work.

In this case, Van Gogh takes up the theme of the peasants; a subject loaded with evangelical and symbolic implications,[4] which he confronted both in his early artistic period at Neunen and in the various copies of the theme in the works of Millet.[25] Unlike the previous paintings, where rural life and the harsh conditions of work in the countryside were evident, the young man here depicted the man living in harmony with a friendly nature,[26] who empathizes with it and with its immutable processes of fertility and regeneration, of life and death.[4] The very stylistic and pictorial solutions he carried out in the portrait denote that attunement, especially in the lines of the composition that make the subject merge with the landscape; in the luminosity of the painting and in the combination of colors.[4]

The young man, who we are not told precisely who he is, appears half bust, in the center of the canvas, as was the case in many other portraits that Van Gogh made that year, such as Portrait of Dr. Rey or Portrait of the chief watchman Trabuc. The painter portrayed the gardener frontally, dividing the mode of representation into two parts: face and bust. He concentrated his attention on the details of the face, which he painted meticulously with small brushstrokes, representing it in an almost photographic way. With this technique, he designed the arched and dense eyebrows, the slightly neglected beard, the tanned skin and the lips, which are delimited by a red line.[2] The expression, slightly somber, is characterized by a look directed downward and, given the small divergence of the pupils, it seems serene but with a certain veil of melancholy.[4]

The beard and hat frame the face, which seems almost symmetrical and is made with small brushstrokes, first in olive green and then in black. The hat—which in addition to those colors includes violet and shades of red and brown—is twisted in such a way that it creates an oblique line towards the left shoulder. The painter designed the bust and shoulders asymmetrically, using a much more immediate technique. The young man wears a white shirt with vertical red and green lines, made with a very fast and dynamic brushstroke, with long strokes and wider than those of the face. This shirt is delimited at the shoulders by a dark line that traces the outline of the protagonist and is characterized by a wavy flow, typical of the expressive quality of Van Gogh's late style.[27]

Underneath the shirt is a yellow and blue horizontally striped shirt, also done with quick vertical brushstrokes and close together. Despite the softer and more muted tones compared to those he used in the Arles period,[7] the peasant's wardrobe contains one of the Dutch author's most significant innovations: the balanced combination of the complementary colors[4] red and green in the shirt and the primary yellow and blue in the shirt.[8] This became one of the most important stylistic elements of his career and greatly influenced new generations of artists such as the Fauves.[28][29]

The background

In this canvas we find a well-defined landscape extending into the distance; something anomalous in Van Gogh's body of work, who portrayed his subjects with monochrome backgrounds, in interiors, or with richly decorated backgrounds, with a wallpaper-like effect, as in the portraits of the Roulin couple. Other portraits with an outdoor setting were Child with Orange (1890), Young Peasant Girl in a Straw Hat sitting in front of a wheatfield (1890) and Girl in White (1890); but in none of them we find the scenic depth and the elaborate composition of the background of The Gardener. However, this can be found in the two copies of the painting Two Girls (both 1890), where in the background some houses can be recognized, and also in Portrait of Dr. Gachet (1890), made with the etching technique and with a fence that limits a garden with hedges and a small plant.

In the background landscape of The Gardener there is a thoughtful and detailed brushstroke that conveys the feeling of the environment where the protagonist is located. On the left is the luminous green of the meadow, done in short, vertical and rhythmic brushstrokes; in colors such as white, yellow, green and blue, which, combined, create a play of shadows cast by the plants in the garden. A little above the shoulder, we notice that the brushstroke becomes horizontal and lightens its tonality, creating an oblique line that follows both the one on the shoulder and the one on the hat, giving shape to a small path. On the right, on the other hand, the brushstroke is more sinuous and chaotic, which is justified by the presence of some bushes.[30]

The period in which he painted The Gardener corresponds to the years when the landscape and the sun of Provence fascinated Van Gogh, when he created the series of olive trees and the paintings dedicated to cypresses and grain fields.[7][31] In the last part of the painting, the vegetation of bushes and plants merges with the meadow, giving the sensation that the grass is developing in tandem with the branches of the trees. The brushstroke is intense yet softly drawn, curved and elegant,[30] taking up technical solutions already experimented with in landscapes painted outdoors,[31][32] to achieve an idea of movement,[7] until ending at the top of the painting, where the rest of the plants and two small walls are present in the distance.

Exhibition venue

The Gardener is in the National Gallery of Modern Art in Rome.[2] Although Van Gogh created approximately 871 paintings[note 1] and a large number of drawings and sketches, only three are in Italian public collections. The other two are L'Arlésienne (Madame Ginoux) (1890),[33] which is preserved in Rome alongside The Gardener, and Breton Women (1888), which remains in the Grasi Collection of the Galleria d'Arte Moderna.[34][35][note 2]

.jpg.webp)

Until 2011, The Gardener was in Room XIV, dedicated to impressionism, its beginnings and its development, alongside works by less famous Italian authors who had gone to Paris to soak up the essence of the new European artistic currents. Given the importance of the work, the room was often called "The Gardener Room."[36] There, the canvas was placed alongside other international works[note 3] such as Return from Fishing (ca. 1900) by Hendrik Willem Mesdag; Poachers in the Snow (1867) by Gustave Courbet, which can be defined as an advance to Impressionist trends; Place Saint-Michelle et la Sainte Chapelle (1896) by Jean-François Raffaelli; Water Lilies in Pink (1897–1899) by Claude Monet and Edgar Degas's pastel painting Apré le bain (ca. 1886); the latter two true protagonists of the French movement; the other canvas by Van Gogh, L'Arlésienne (Madame Ginoux) and the painting Le cabanon de Jourdan (1906) by Cézanne, protagonist of post-impressionism.

Regarding the Italian artists, were present the three great works of Giuseppe De Nittis dedicated to The races in Bois de Boulogne of 1881; the work Dreams by Vittorio Matteo Corcos; the famous Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi (1886) by Giovanni Boldini; the portrait of The son Edward, with Egisto Fabbri and Alfredo Muller (1895) by Michele Gordigiani and two sculptures by Medardo Rosso, one of them the Portrait of Henry Ruart (1889–1890), whom critics consider the only truly impressionist sculptor.[37][38]

On December 21, 2011, the museum reopened to the public with a new exhibition itinerary.[39] All the works previously included in "The Gardener Room", except for the two Van Goghs, remained in Room XIV, entitled "The Impressionist Question", where more sculptures were included-two by Edgar Degas and the entire collection dedicated to Medardo Rosso. The Van Goghs, instead, were moved to Room XV, titled "The Humanitarian Utopia," and placed on a loose wall in the center of the room so that they are the first works visitors encounter on their itinerary.[40]

Both canvases are exhibited alongside Il sole (1904) by Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Il mendicante (1902), I malati (1903) and La pazza (1905) by Giacomo Balla, Il viatico (1884) by Angelo Morbelli, Il viaggio della vita (1905) by John Quincy Adams, Retirando las redes (1896) by Joaquín Sorolla, After Tired Work (1910) by Döme Skuteczky, Contadino al lavoro (1908–1910) by Umberto Boccioni, The Meal (1910–1914) by Albin Egger Lienz, The Workers (1905) by Costantino Meunier, Nosocomio (1895) by Silvio Rotta and Ritratto di Giovanni Cena (ca. 1909) by Felice Carena.[40]

Therefore, The Gardener is a fundamental work in the brief chronological and artistic journey that the museum creates around the impressionist current, plenairist art and studies dedicated to color.[37] The Gardener is a link with the artists who dedicated their art and their careers to the symbolist innovations and to the mixture between socialism and positivism, without forgetting social marginalization, a theme that Van Gogh always touched in his works in a very sensitive way.[39]

In any case, over the years, the painting The Gardener has also been the subject of different loans for temporary exhibitions, coming to be exhibited both in other Italian cities such as Genoa[41] and Siena,[42] as well as outside Italy, in cities such as Vienna[43] or Philadelphia.[44] In addition, the painting has been part of different temporary exhibitions showing paintings recovered by the Arma dei Carabinieri after some theft, held in Rome in 1999[45] and 2004.[41]

Notes

- The catalogued works are 871, but the number oscillates because of doubts about the attribution of some works.

- Data extracted from the list of Van Gogh's complete works.

- The works in the room could vary, depending on temporary loans or upon exhibition changes.

References

- Bardazzi & Sborgi (2007, p. 180)

- Walther & Metzger (2006, p. 540)

- Di Majo & Lafranconi (2006, p. 290)

- Cabella & Frezzotti (2004, p. 110)

- Jansen, Leo; Hans, Luijten; Nienke, Bakker. "Vincent van Gogh — The Letters". vangoghletters.org.

- Walther & Metzger (2006, p. 11)

- "Vincent van Gogh, un breve perfil". vangoghmuseum.nl (in Spanish).

- "Il giardiniere". Cultura Italia (in Italian).

- van Gogh, Vincent. "To Theo van Gogh. Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Thursday, 5 and Friday, 6 September 1889". vangoghletters.org.

- Biolchini, Stefano (2 March 2007). "Firenze ritrova i capolavori "smarriti" di Paul Cezanne". Il Sole 24 Ore. Firenze.

- Bardazzi & Sborgi (2007, p. 168).

- "Il giardiniere". CulturaItalia.

- "Che imprudenza". Il Corriere della Sera. 22 May 1998.

- Fioretti, Sabelli (16 March 2006). "Intervista a Verusio" (in Italian).

- "Quando Van Gogh abitava con noi" (in Italian). 22 May 1998.

- Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali (29 May 2002). "Il Giardiniere di Van Gogh resta in Italia. Soddisfazione del ministro Urbani" (in Italian).

- "Il giardiniere di Van Gogh resta a Roma". La repubblica (in Italian). 29 May 2002.

- "Europa boccia Italia per Van Gogh". Il Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 6 January 2000.

- "Il giardiniere verrà a Roma". Il Corriere della Sera (in Italian). 21 June 1995.

- "Roma, rubati nel museo due Van Gogh e un Cezanne". La Repubblica (in Italian). Rome. 20 May 1998.

- Brogi, Paolo (8 July 1998). ""Studiato" al bar il furto dei Van Gogh". Corriere della Sera (in Italian). Rome. p. 16. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016.

- "Portrait of a Lady: Painting found in wall confirmed as stolen Klimt". BBC News. 17 January 2020.

- Walther & Metzger (2006, p. 515)

- "To Anna van Gogh-Carbentus. Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Thursday, 19 September 1889". vangoghletters.org.

- "Il giardiniere". La Galleria Nazionale.

- "Vincent Van Gogh Campagna Senza Tempo - Città Moderna". vediromainbici.it. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013.

- "Retrato del Doctor Gachet". National Gallery of Canada.

- "fauvismo". sapere.it (in Italian). De Agostini.

- Peccatori, Zuffi & Torterolo (1998, p. 130).

- Walther & Metzger (2006, p. 510)

- Vergeest et al. (2008, p. 218)

- Walther & Metzger (2006, p. 517)

- Walther & Metzger (2006, p. 617)

- Walther & Metzger (2006, p. 472)

- Walther & Metzger (2006).

- "Lista de salas de la GNAM". Romartguide.it (in Italian).

- Benedetti, Giuditta. "Tre Sale della Galleria de Arte Moderna" (PDF) (in Italian). caosmanagement.it.

- "Visione tridimensionale della sala". Studio Argento. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013.

- Sassi, Edoardo (21 December 2011). "Galleria nazionale d'arte Moderna, riordinamento per temi e tendenze". Corriere della Sera. Rome.

- "Sala 15 - L'utopia umanitaria". Galería Nacional de Arte Moderno.

- "Tesori ritrovati". palazzoducale.genova.it (in Italian). Palacio Ducal de Génova. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013.

- "Arte, genio e follia in mostra a Siena". civita.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 16 July 2014.

- "Vincent Van Gogh, draws and pictures". Archived from the original on 17 November 2011.

- "Van Gogh Portraits Prominent in Detroit, Boston and Philadelphia Museum Collections". Philadelphia Museum of Art. 9 August 2000. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- Piperno, Antonella (17 March 1999). "Van Gogh a Castel Sant' Angelo". La Repubblica. Rome. p. 6.

Bibliography

- Bardazzi, Francesca; Sborgi, Francesca (2007). Cézanne a Firenze. Due collezionisti e la mostra dell'impressionismo del 1910 (in Italian). Mondadori Electa. ISBN 978-88-370-5108-2.

- Di Majo, E.; Lafranconi, M. (2006). Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna. Le collezioni. Il XIX secolo (in Italian). Milano: Electa. ISBN 978-88-370-4365-0.

- Peccatori, Stefano; Zuffi, Stefano; Torterolo, Anna (1998). ArtBook Van Gogh (in Italian). Martellago (Venezia): Leonardo Arte. ISBN 88-7813-828-2.

- Pellegrino, Francesco (2013). Ore 22, furto in galleria (in Italian). Marino (Roma) con una nota introduttiva di Walter Veltroni: Natyvi Contemporanea. ISBN 978-88-906370-4-9.

- Toncini Cabella, A.; Frezzotti, Stefania (2004). Tesori ritrovati. Carabinieri per l'arte nell'arte (in Italian). Rome: De Luca editori d'arte. ISBN 88-8016-596-8.

- Vergeest, Aukje; Meedendorp, Teio; van Straaten, Evert; Goldin, Marco; Verhoog, Robert (2008). Van Gogh disegni e dipinti — Capolavori dal Kröller - Müller Museum (in Italian). Crocetta del Montello (TV): Linea d'Ombra Libri. ISBN 978-88-89902-30-1.

- Walther, Ingo F.; Metzger, Rainer (2006). Van Gogh tutti i dipinti (in Italian). Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-5218-7.