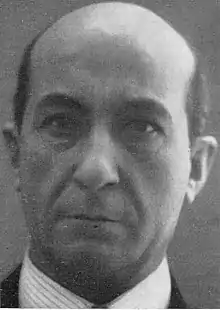

Ardengo Soffici

Ardengo Soffici (7 April 1879 – 19 August 1964) was an Italian writer, painter, poet, sculptor and intellectual.

Early life

Soffici was born in Rignano sull'Arno, near Florence. In 1893 his family moved to the latter city, where he studied at the Accademia from 1897 and later at the Scuola Libera del Nudo of the academy.

Career

In 1900 he moved from Florence to Paris,[1] where he lived for seven years and worked for Symbolist journals. While in Paris, during his time at the Bateau-Lavoir,[2] he became acquainted with Braque, Derain, Picasso, Juan Gris and Apollinaire.

On returning to Italy in 1907, Soffici settled in Poggio a Caiano in the countryside near Florence (where he lived for the rest of his life) and wrote articles on modern artists for the first issue of the political and cultural magazine La Voce.

In 1910 he organised an exhibition of Impressionist painting in Florence in association with La Voce, devoting an entire room to the sculptor Medardo Rosso.

In August 1911 he wrote an article in La Voce on Picasso and Braque, which probably influenced the Futurists in the direction of Cubism.[3] At this time Soffici considered Cubism to be an extension of the partial revolution of the Impressionists. In 1912-1913 Soffici painted in a Cubist style.

Futurism

After visiting the Futurists' Exhibition of Free Art in Milan, he wrote a hostile review in La Voce. The leading Futurists Marinetti, Boccioni and Carrà, were so incensed by this that they immediately boarded a train for Florence and assaulted Soffici and his La Voce colleagues at the Caffè Giubbe Rosse.[4] Reviewing the Futurists' Paris exhibition of 1912 in his article Ancora del Futurismo (Futurism Again) he dismissed their rhetoric, publicity-seeking and their art, but granted that, despite its faults, Futurism was "a movement of renewal, and that is excellent".

Gino Severini was despatched from Milan to Florence to make peace with Soffici on behalf of the Futurists – the Peace of Florence, as Boccioni called it. After these diplomatic overtures, Soffici, together with Giovanni Papini, Aldo Palazzeschi and Italo Tavolato withdrew from La Voce in 1913 to form a new periodical, Lacerba, which would concentrate entirely on art and culture. Soffici published "Theory of the movement of plastic Futurism" in Lacerba, accepting that Futurism had reconciled what had previously seemed irreconcilable, Impressionism and Cubism. By its fifth issue Lacerba wholly supported the Futurists. Soffici's paintings in 1913 – e.g. Linee di una strada and Sintesi di una pesaggio autumnale – showed the influence of the Futurists in method and title and he exhibited with them.

In 1914, personal quarrels and artistic differences between the Milan Futurists and the Florence group around Soffici, Papini and Carlo Carrà, created a rift in Italian Futurism. The Florence group resented the dominance of Marinetti and Boccioni, whom they accused of trying to establish "an immobile church with an infallible creed", and each group dismissed the other as passéiste.

Inter-war years

After serving in the First World War, Soffici married Maria Sdrigotti, whom he met in a publishing house in Udine, while editing Kobilek. They moved to Poggio a Caiano and had three children, Valeria, Sergio and Laura. Soffici created a distance from Futurism and, discovering a new reverence for Tuscan tradition, became associated with the "return to order" which manifested itself in the naturalistic landscapes which thereafter dominated his work. Remaining in Poggio a Caiano, he painted nature and traditional Tuscan scenes. There, he continued to write and paint and was visited by many artists, some of whom he helped in finding their place in the art world. In 1926, he discovered the young artist Quinto Martini when the latter visited Soffici's workshop with his work. In Martini's first experiments Soffici recognised the kind of genuine and intimate traits he was seeking and became his mentor.

In 1925, he signed the Manifesto degli intellettuali fascisti in support of the regime, and in 1938 he gave support to Italy's racial laws. In 1932 Soffici published articles on his experience in Paris in the early years of the 20th century in the magazine Il Selvaggio.[5]

Later life

When Mussolini was overthrown in Italy, he pledged loyalty to the Italian Social Republic with Mussolini as its head. He was a co-founder of Italia e Civilità, a war magazine that supported patriotism, Germany and the principles of Fascism.

At the end of the Second World War, Soffici was taken as a British POW and was imprisoned for several months in unhealthy conditions at an allied prison camp where he contracted pneumonia. During his stay at the prison camp, he met several other artists and writers who had also been accused of political support to fascism. Together, they wrote, painted and set up plays to pass the time in the squalid conditions they found themselves in. Some of the paintings were exchanged for food and art materials from the guards. Later, once released due to lack of evidence, he returned home and lived in Poggio a Caiano and spent his summers in Forte dei Marmi.

Death

Soffici continued to paint and write until his death in Forte dei Marmi on 12 August 1964. His last photo was taken a few days before his demise, holding his youngest granddaughter Marina.[6]

Bibliography

Poems

- BÏF§ZF+18 = Simultaneità - Chimismi lirici (1915)

- Elegia dell'Ambra (1927)

- Marsia e Apollo (1938)

- Thréne pour Guillame Apollinaire (1927)

Novels

- Ignoto toscano (1909)

- Lemmonio Boreo (1912)

- Arlecchino (1914)

- Giornale di bordo (1915)

- Kobilek: giornale di battaglia (1918)

- La giostra dei sensi (1918)

- La ritirata del Friuli (1919)

- Rete mediterranea (1920)

- Battaglia fra due vittorie (1923)

- Ricordi di vita artistica e letteraria (1931)

- Taccuino di Arno Borghi (1933)

- Ritratto delle cose di Francia (1934)

- L'adunata (1936)

- Itinerario inglese (1948)

- Autoritratto d'artista italiano nel quadro del suo tempo

- L'uva e la croce (1951)

- Passi tra le rovine (1952)

- Il salto vitale (1954)

- Fine di un mondo (1955)

- D'ogni erba un fascio (1958)

- Diari 1939-1945 (1962, with G. Prezzoloni)

Essays

- Il caso Rosso e l'impressionismo (1909)

- Arthur Rimbaud (1911)

- Cubismo e oltre (1913)

- Cubismo e futurismo (1914)

- Serra e Croce (1915)

- Cubismo e futurismo (1919)

- Scoperte e massacri (1919)

- Primi principi di un'estetica futurista (1920)

- Giovanni Fattori (1921)

- Armando Spadini (1925)

- Carlo Carrà (1928)

- Periplo dell'arte (1928)

- Medardo Rosso: 1858-1928 (1929)

- Ugo Bernasconi (1934)

- Apollinaire (1937)

- Salti nel tempo (1938)

- Selva: arte (1938)

- Trenta artisti moderni italiani e stranieri (1950)

References and sources

- References

- "Estorick Collection". Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- "Montmartre". Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Martin, Marianne W. Futurist Art and Theory, Hacker Art Books, New York, 1978, p.104

- Martin, p.81

- Flora Ghezzo (January 2010). "Topographies of Disease and Desire: Mapping the City in Fascist Italy". Modern Language Notes. 125 (1): 205. doi:10.1353/mln.0.0227.

- Laura Poggi Soffici

- Sources

- Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art

- Raimondi, Giuseppe; Luigi Cavallo (1967). Ardengo Soffici. Florence: Vallecchi.