History of Sindh

The history of Sindh refers to the history of the Pakistani province of Sindh, as well as neighboring regions that periodically came under its sway.

| History of Sindh |

|---|

|

| History of Pakistan |

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

Sindh was the site of one of the Cradle of civilizations, the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilisation that flourished from about 3000 B.C. and declined rapidly 1,000 years later, following the Indo-Aryan migrations that overran the region in waves between 1500 and 500 B.C.[1] The migrating Indo-Aryan tribes gave rise to the Iron Age vedic civilization, which lasted till 500 BC. During this era, the Vedas, the oldest and primary Hindu scriptures were composed. In 518 BC, the Achaemenid empire conquered Indus valley and established Hindush satrapy in Sindh. Following Alexander the Great's invasion, Sindh became part of the Mauryan Empire. After its decline, Indo-Greeks, Indo-Scythians and Indo-Parthians ruled in Sindh.

Sindh is sometimes referred to as the Bab-ul Islam (transl. 'Gateway of Islam'), as it was one of the first regions of the Indian subcontinent to fall under Islamic rule. Parts of the modern-day province were intermittently subject to raids by the Rashidun army during the early Muslim conquests, but the region did not fall under Muslim rule until the Arab invasion of Sind occurred under the Umayyad Caliphate, headed by Muhammad ibn Qasim in 712 CE.[2][3] Afterwards, Sindh was ruled by a series of dynasties including Habbaris, Soomras, Sammas, Arghuns and Tarkhans. The Mughal empire conquered Sindh in 1591 and organized it as Subah of Thatta, the first-level imperial division. Sindh again became independent under Kalhora dynasty. The British conquered Sindh in 1843 AD after Battle of Hyderabad from the Talpur dynasty. Sindh became separate province in 1936, and after independence became part of Pakistan.

Sindh is home to two UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites: the Makli Necropolis and Mohenjo-daro.[4]

Etymology

The Greeks who conquered Sindh in 325 BC under the command of Alexander the Great referred to the Indus River as Indós, hence the modern Indus. The ancient Iranians referred to everything east of the river Indus as hind.[5][6] The word Sindh is a Persian derivative of the Sanskrit term Sindhu, meaning "river" - a reference to Indus River.[7] Southworth suggests that the name Sindhu is in turn derived from Cintu, a Dravidian word for date palm, a tree commonly found in Sindh.[8][9]

The previous spelling "Sind" (from the Perso-Arabic سند) was discontinued in 1988 by an amendment passed in Sindh Assembly,[10] and is now spelt "Sindh."

Bronze age

Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1300 BC)

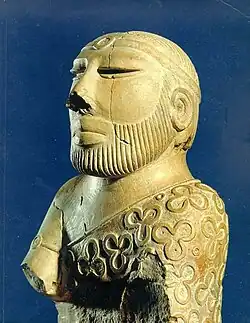

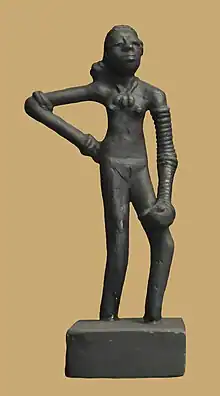

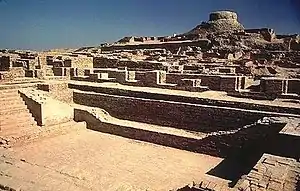

Sindh and surrounding areas contain the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization. There are remnants of thousand-year-old cities and structures, with a notable example in Sindh being that of Mohenjo Daro. Built around 2500 BCE, it was one of the largest settlements of the ancient Indus civilisation or Harappan culture, with features such as standardized bricks, street grids, and covered sewerage systems.[11] It was one of the world's earliest major cities, contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, and Caral-Supe. Mohenjo-daro was abandoned in the 19th century BCE as the Indus Valley Civilization declined, and the site was not rediscovered until the 1920s. Significant excavation has since been conducted at the site of the city, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980.[12] The site is currently threatened by erosion and improper restoration.[13]

The cities of the ancient Indus were noted for their urban planning, baked brick houses, elaborate drainage systems, water supply systems, clusters of large non-residential buildings, and techniques of handicraft and metallurgy.[lower-alpha 1] Mohenjo-daro and Harappa very likely grew to contain between 30,000 and 60,000 individuals,[15] and the civilisation may have contained between one and five million individuals during its florescence.[16] A gradual drying of the region during the 3rd millennium BCE may have been the initial stimulus for its urbanisation. Eventually it also reduced the water supply enough to cause the civilisation's demise and to disperse its population to the east.[lower-alpha 2]

Iron age (c. 1300 – c. 518 BC)

Sindhu-Sauvera kingdoms

.png.webp)

Sindhu-Sauvīra (Sanskrit: Sindhu-Sauvīra; Pāli: Sindhu-Sovīra) was an ancient Indo-Aryan kingdom of western South Asia whose existence is attested during the Iron Age. The inhabitants of Sindu were called the Saindhavas, and the inhabitants of Sauvīra were called Sauvīrakas.

The territory of Sindhu-Sauvīra covered the lower Indus Valley,[17] with its southern border being the Indian Ocean and its northern border being the Punjab around Multan.[18]

Sindhu was the name of the inland area between the Indus River and the Sulaiman Mountains, while Sauvīra was the name for the coastal part of the kingdom as well as the inland area to the east of the Indus river as far north as the area of modern-day Multan.[18]

The capital of Sindhu-Sauvīra was named Roruka and Vītabhaya or Vītībhaya, and corresponds to the mediaeval Arohṛ and the modern-day Rohṛī.[18][19][20]

Ancient history

Achaemenid Era (516–326 BC)

Achaemenid empire may have controlled parts of present-day Sindh as part of the province of Hindush. The territory may have corresponded to the area covering the lower and central Indus basin (present day Sindh and the southern Punjab regions of Pakistan).[21] To the north of Hindush was Gandāra (spelt as Gandāra by the Achaememids). These areas remained under Persian control until the invasion by Alexander.[22]

Alternatively, some authors consider that Hindush may have been located in the Punjab area.[23]

Hellenistic era (326–317 BC)

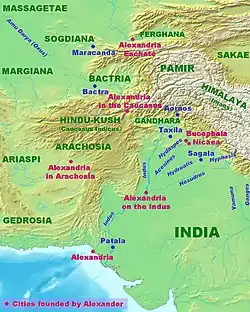

Alexander conquered parts of Sindh after Punjab for few years and appointed his general Peithon as governor. The ancient city of Patala was located at the mouth of the Indus River. The Indus parted into two branches at the city of Patala before reaching the sea, and the island thus formed was called Patalene, the district of Patala. Alexander constructed a harbour at Patala.[26][27]

Some scholars identify Patala with Thatta, a one-time capital of Sindh.[24][25] But the identity of Patala is much debated among scholars.

Siltation has caused the Indus to change its course many times since the days of Alexander the Great, and the site of ancient Patala has been subject to much conjecture.[28]

Mauryan Era (316–180 BC)

Chandragupta Maurya had established his empire around 320 BC. The early life of Chandragupta Maurya is not clear. Janapadas of Punjab and Sindh, he had gone on to conquer much of the North West. He then defeated the Nanda rulers in Pataliputra to capture the throne. Chandragupta Maurya fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus I Nicator, when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus River and offered a marriage, including a portion of Bactria, while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants.[29]

The Mauryan Empire, under king Ashoka introduced Buddhism in Sindh.[30][31][32] Hinduism is the oldest-recorded religion in Sindh and was the predominant religion of the Sindhi people, prior to the arrival of Buddhism in the 3rd century BCE.[33]

Indo-Greek era (180–90 BC)

Following a century of Mauryan rule which ended by 180 BC, the region came under the Indo-Greeks. According to Apollodorus of Artemita, quoted by Strabo, the Indo-Greek territory of Sindh was known as Sigerdis.[34]

Indo Scythians (90–20 BC)

The Indo Scythians ruled Sindh with its capital at Minnagara.[35] It was located on the Indus river, north of the coastal city of Barbaricum, or along the Narmada river, upstream of Barygaza. There were two cities named Minnagara, one on Indus River delta near Karachi and the other at Narmada River delta near modern Bharuch.[36] The Ptolemy world map, as well as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mention prominently, the country of Scythia on the Indus Valley, as well as Roman Tabula Peutingeriana.[37] The Periplus states that Minnagara was the capital of Scythia, and that Parthian Princes from within it were fighting for its control during the 1st century CE.

Gupta Empire (345-455 AD)

Sindh came under the Gupta Empire, which reached its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, covering much of the Indian subcontinent. Hindu art and culture flourished again during this era. The Famous bronze of the Hindu god, Brahma has been excavated from Mirpur khas. Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala calls it "an exceptionally good specimen of the art of metal-casting in this period".[38] Śrīrāma and Śaṅkara Goyala term is "true memorial of Gupta metalsmith's artistic genius".[39] It is said to the best example of Gupta art in Sindh.[40] The object suggests that Sindh was a major centre of metalworking.[41] The Brahma from Mirpur Khas has been widely used by art historians for comparison with other artwork of historical significance.[42][43] The Kahu-Jo-Darro stupa is an ancient Buddhist stupa found at the Mirpurkhas archaeological site from the western Satraps era.[44][45][46] Early estimates placed the site in the 4th to 5th-century. The stupa is now dated between the 5th to early 6th-century, because its artwork is more complex and resembles those found in the dated sites such as the Ajanta and Bhitargaon in India.[45][47][48] The Prince of Wales Museum describes the style of Mirpur Khas stupa as a conflation of the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, and Gupta art:

"The terracotta figures of Mirpur Khas represent the Gupta Empire as it flourished in Sindh. (...) In the terracottas of Mirpur Khas, of which the Museum has a most representative collection, one may see the synthesis of Gandhara and Gupta traditions . Here the old sacrosanct forms of Gandhara are moulded in the Gupta character of nobility , restraint and spirituality and the result is very pleasing. The figures of the Buddha from Mirpur Khas show transformation from the Gandhara to Gupta idiom , which the figures of the donor and Kubera show well developed Gupta types."

— Prince of Wales Museum of Western India[49]

Buddhism despite having a long illustrious history in Sindh, declined during the reign of the Gupta Empire, due to preference given to the propagation of Hinduism again in the region. Hinduism soon became the predominant religion in the province again.[33][50][51]

Sassanian Empire (325–489 AD)

Sasanian rulers from the reign of Shapur I claimed control of the Sindh area in their inscriptions. Shapur I installed his son Narseh as "King of the Sakas" in the areas of Eastern Iran as far as Sindh.[54] Two inscriptions during the reign of Shapur II mention his control of the regions of Sindh, Sakastan and Turan.[55] Still, the exact term used by the Sasanian rulers in their inscription is Hndy, similar to Hindustan, which cannot be said for sure to mean "Sindh".[52] Al-Tabari mentioned that Shapur II built cities in Sind and Sijistan.[56][57]

Rai Dynasty (c. 489 – 632 AD)

.png.webp)

The Rai dynasty of Sindh was the first dynasty of Sindh and at its height of power ruled much of the Northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. The dynasty reigned for a period of 144 years, c. 489 – 632 AD, concurrent with the Huna invasions of North India.[59] The names of rulers might have been corruptions of Sanskrit names — Devaditya, Harsha, and SInhasena.[59][60] The origins of the dynasty, caste status, and how they rose to power remains unknown.[59][60] They apparently had familial ties with other rulers of South Asia including Kashmir, Kabul, Rajasthan, Gujarat, etc. — Aror is noted to be the capital of both Hind and Sindh.[59][61] Alexander Cunningham had proposed an alternate chronology (? – >641 AD) — primarily on the basis of numismatic and literary evidence[lower-alpha 3] — identifying the first two Rais as Hunas and the later three as rulers of Zabulistan and Khorasan.[60][lower-alpha 4] However, there exists little historical evidence to favor the proposition of Hunas ever making to Sindh and the individual bases of his hypothesis stands discredited in modern scholarship.[60] Chintaman Vinayak Vaidya supported Cunningham's chronology (? – >641 AD) but held the Rais to be descendants of Mauryas and Shudra, by caste.[60][lower-alpha 5]

Harsha Empire

Harshacharitta, a biography written by Banabhatta mentions King Harsha badly defeated the ruler of Sindh and took possession of his fortunes.[62]

Brahmin dynasty (c. 632 – c. 724 AD)

The Brahmin dynasty of Sindh (c. 632 – 712),[64] also known as the Chacha dynasty,[65] were the Sindhi Hindu Brahmin ruling family of the Chacha Empire. The Brahmin dynasty were successors of the Buddhist Rai dynasty. The dynasty ruled on the Indian subcontinent which originated in the region of Sindh, present-day Pakistan. Most of the information about its existence comes from the Chach Nama, a historical account of the Chach-Brahmin dynasty.

Chinese traveller, Hieun Tsang, who had visited the Sindh region during the start of the Chacha rule, described in his work that Buddhism had declined in the region and Brahminical Hinduism had once again gained the majority dominance.[66][67]

Hinduism was the predominant religion in Sindh under the Chacha empire, prior to the arrival of Islam with the Arab invasions, although a significant minority of the Sindhi population adhered to Buddhism as well.[68] Hindus made up almost two-thirds of the ethnic Sindhi population before the arrival of Islam in the region.[33] At the time of the invasions, Sindhi Hindus were a rural pastoral population, majority of whom lived in upper Sindh, a region that was entirely Hindu;[69] whereas Buddhists were a mercantile population, almost entirely concentrated in the urban areas between lower Sindh and Makran, a region that was equally divided in population between Buddhists and Hindus.[69]

The primary sources describe that Buddhists in Sindh collaborated[70][71] and sided[72] with the Arabs, before the invasion even began.[73] The Islamic Arab invasion of Sindh were only made successful, because leaders of the Buddhist community despised and opposed the local Brahmin ruler, hence sympathizing with the Arab invaders and even helping them in times.[74]

On the other hand, Sindhi Hindu resistance against the Arabs continued for much longer, both in upper Sindh and Multan.[75] During the conflict, the western Buddhist Jats aligned with the invading Arab army led by Muhammad bin Qasim against the local Hindu ruler Raja Dahir, whereas the eastern Hindu Jats supported Dahir, against the invaders.[76]

After the Chacha Empire's fall in 712, though the empire had ended, its dynasty's members administered parts of Sindh under the Umayyad Caliphate's Caliphal province of Sind.[64] These rulers include Hullishāh and Shishah.[64]

Medieval era

Arab Sindh (711–854 AD)

After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Arab expansion towards the east reached the Sindh region beyond Persia. An initial expedition in the region launched because of the Sindhi pirate attacks on Arabs in 711–12, failed.[77][78]

The first clash with the Hindu kings of Sindh took place in 636 (15 A.H.) under Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab with the governor of Bahrain, Uthman ibn Abu-al-Aas, dispatching naval expeditions against Thane and Bharuch under the command of his brother, Hakam. Another brother of his, al-Mughira, was given the command of the expedition against Debal.[79] Al-Baladhuri states they were victorious at Debal but doesn't mention the results of other two raids. However, the Chach Nama states that the raid of Debal was defeated and its governor killed the leader of the raids.[80]

These raids were thought to be triggered by a later pirate attack on Umayyad ships.[81] Uthman was warned by Umar against it who said "O brother of Thaqif, you have put the worm on the wood. I swear, by Allah that if they had been smitten, I would have taken the equivalent (in men) from your families." Baladhuri adds that this stopped any more incursions until the reign of Uthman.[82]

Majority of the Sindh region's native Sindhi population at the time of the Umayyad invasions, prior to the arrival of Islam, followed Hinduism, but a significant minority adhered to Buddhism as well.[68] In 712, when Mohammed Bin Qasim invaded Sindh with 8000 cavalry while also receiving reinforcements, Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf instructed him not to spare anyone in Debal. The historian al-Baladhuri stated that after conquest of Debal, Qasim kept slaughtering its inhabitants for three days. The custodians of the Buddhist stupa were killed and the temple was destroyed. Qasim gave a quarter of the city to Muslims and built a mosque there.[83] According to the Chach Nama, after the Arabs scaled Debal's walls, the besieged denizens opened the gates and pleaded for mercy but Qasim stated he had no orders to spare anyone. No mercy was shown and the inhabitants were accordingly thus slaughtered for three days, with its temple desecrated and 700 women taking shelter there enslaved. At Ror, 6000 fighting men were massacred with their families enslaved. The massacre at Brahamanabad has various accounts of 6,000 to 26,000 inhabitants slaughtered.[84]

60,000 slaves, including 30 young royal women, were sent to al-Hajjaj. During the capture of one of the forts of Sindh, the women committed the jauhar and burnt themselves to death according to the Chach Nama.[84] S.A.A. Rizvi citing the Chach Nama, considers that conversion to Islam by political pressure began with Qasim's conquests. The Chach Nama has one instance of conversion, that of a slave from Debal converted at Qasim's hands.[85] After executing Sindh's ruler, Raja Dahir, his two daughters were sent to the caliph and they accused Qasim of raping them. The caliph ordered Qasim to be sewn up in hide of a cow and died of suffocation.[86]

Habbari Arab dynasty (854–1024)

The third dynasty, Habbari dynasty ruled much of Greater Sindh, as a semi-independent emirate from 854 to 1024. Beginning with the rule of 'Umar bin Abdul Aziz al-Habbari in 854 CE, the region became semi-independent from the Abbasid Caliphate in 861, while continuing to nominally pledge allegiance to the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad.[87][88] The Habbari ascension marked the end of a period of direct rule of Sindh by the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, which had begun in 711 CE. The Habbaris were based in the city of Mansura, and ruled central and southern Sindh south of Aror,[89] near the modern-day metropolis of Sukkur. The Habbaris ruled Sindh until they were defeated by Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi in 1026, who then went on to destroy the old Habbari capital of Mansura, and annex the region to the Ghaznavid Empire, thereby ending Arab rule of Sindh.

Ghaznavids

Some of the territory in Sindh found itself under raids from the Turkic ruler, Mahmud Ghaznavi in 1025, who ended Arab rule of Sindh.[90] During his raids of northern Sindh, the Arab capital of Sindh, Mansura, was largely destroyed.[91]

Soomra dynasty (1011–1333)

The Soomra dynasty was a local Sindhi Muslim dynasty of Hindu origin[92] that ruled between early 11th century and the 14th century.[93][94] Many rulers of the dynasty even bore Hindu first names.[92]

Later chroniclers like Ali ibn al-Athir (c. late 12th c.) and Ibn Khaldun (c. late 14th c.) attributed the fall of Habbarids to Mahmud of Ghazni, lending credence to the argument of Hafif being the last Habbarid.[95] The Soomras appear to have established themselves as a regional power in this power vacuum.[95][96]

The Ghurids and Ghaznavids continued to rule parts of Sindh, across the eleventh and early twelfth century, alongside Soomrus.[95] The precise delineations are not yet known but Sommrus were probably centered in lower Sindh.[95]

Some of them were adherents of Isma'ilism.[96] One of their kings Shimuddin Chamisar had submitted to Iltutmish, the Sultan of Delhi, and was allowed to continue on as a vassal.[97]

Samma dynasty (1333–1520)

The Samma dynasty was a Sindhi dynasty that ruled in Sindh, and parts of Kutch, Punjab and Balochistan from c. 1351 to c. 1524 CE, with their capital at Thatta.[99][100][101]

The Sammas overthrew the Soomras soon after 1335 and the last Soomra ruler took shelter with the governor of Gujarat, under the protection of Muhammad bin Tughluq, the sultan of Delhi. Mohammad bin Tughlaq made an expedition against Sindh in 1351 and died at Sondha, possibly in an attempt to restore the Soomras. With this, the Sammas became independent. The next sultan, Firuz Shah Tughlaq attacked Sindh in 1365 and 1367, unsuccessfully, but with reinforcements from Delhi he later obtained Banbhiniyo's surrender. For a period the Sammas were therefore subject to Delhi again. Later, as the Sultanate of Delhi collapsed they became fully independent.[102] Jam Unar was the founder of Samma dynasty mentioned by Ibn Battuta.[102]

The Samma civilization contributed significantly to the evolution of the Indo-Islamic architectural style. Thatta is famous for its necropolis, which covers 10 square km on the Makli Hill.[103] It has left its mark in Sindh with magnificent structures including the Makli Necropolis of its royals in Thatta.[104][105]

Arghun dynasty (1520–1591)

The Arghun dynasty were a dynasty of either Mongol,[106] Turkic or Turco-Mongol ethnicity,[107] who ruled over the area between southern Afghanistan, and Sindh from the late 15th century to the early 16th century as the Sindh's sixth dynasty. They claimed their descent and name from Ilkhanid-Mongol Arghun Khan.[108]

Arghun rule was divided into two branches: the Arghun branch of Dhu'l-Nun Beg Arghun that ruled until 1554, and the Tarkhan branch of Muhammad 'Isa Tarkhan that ruled until 1591 as the seventh dynasty of Sindh.[107]

Early modern era

Mughal Era (1591–1701)

In the late 16th century, Sindh was brought into the Mughal Empire by Akbar, himself born in the Rajputana kingdom in Umerkot in Sindh.[109][110] Mughal rule from their provincial capital of Thatta was to last in lower Sindh until the early 18th century, while upper Sindh was ruled by the indigenous Kalhora dynasty holding power, consolidating their rule until the mid-18th century, when the Persian sacking of the Mughal throne in Delhi allowed them to grab the rest of Sindh. It is during this the era that the famous Sindhi Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai composed his classic Sindhi text "Shah Jo Risalo" [111][112][113]

Kalhora dynasty (1701–1783)

The Kalhora dynasty was a Sunni dynasty based in Sindh.[111][112] This dynasty as the eighth dynasty of Sindh ruled Sindh and parts of the Punjab region between 1701 and 1783 from their capital of Khudabad, before shifting to Hyderabad from 1768 onwards.

Kalhora rule of Sindh began in 1701 when Mian Yar Muhammad Kalhoro was invested with title of Khuda Yar Khan and was made governor of Upper Sindh sarkar by royal decree of the Mughals.[114] Later, he was made governor of Siwi through imperial decree. He founded a new city Khudabad after he obtained from Aurangzeb a grant of the track between the Indus and the Nara and made it the capital of his kingdom. Thenceforth, Mian Yar Muhammad became one of the imperial agents or governors. Later he extended his rule to Sehwan and Bukkur and became sole ruler of Northern and central Sindh except Thatto which was still under the administrative control of Mughal Empire.[114]

The Kalhora dynasty succumbed to the Afghan Qizilbash during the invasion of Nadir Shah. Mian Ghulam Shah Kalhoro reorganised and consolidated his power, but his son lost control of Sindh and was overthrown by Talpurs Amirs. Mian Abdul Nabi Kalhoro was the last Kalhora ruler.[115]

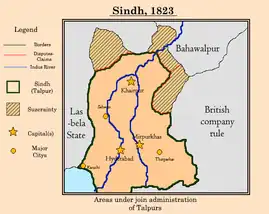

Talpur dynasty (1783–1843)

The Talpur dynasty (Sindhi: ٽالپردور; Urdu: سلسله تالپور) succeeded the Kalhoras in 1783 and four branches of the dynasty were established.[116] One ruled lower Sindh from the city of Hyderabad, another ruled over upper Sindh from the city of Khairpur, a third ruled around the eastern city of Mirpur Khas, and a fourth was based in Tando Muhammad Khan. They were ethnically Baloch,[117] and for most of their rule, they were subordinate to the Durrani Empire and were forced to pay tribute to them.[118][119]

They ruled from 1783, until 1843, when they were in turn defeated by the British at the Battle of Miani and Battle of Dubbo.[120] The northern Khairpur branch of the Talpur dynasty, however, continued to maintain a degree of sovereignty during British rule as the princely state of Khairpur,[117] whose ruler elected to join the new Dominion of Pakistan in October 1947 as an autonomous region, before being fully amalgamated into West Pakistan in 1955.

Modern era

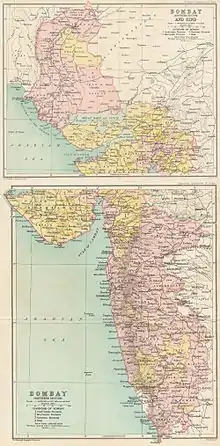

British Rule (1843–1947)

The British conquered Sindh in 1843. General Charles Napier is said to have reported victory to the Governor General with a one-word telegram, namely Peccavi – or I have sinned (Latin).[121]

The British had two objectives in their rule of Sindh: the consolidation of British rule and the use of Sindh as a market for British products and a source of revenue and raw materials. With the appropriate infrastructure in place, the British hoped to utilise Sindh for its economic potential.[122]

The British incorporated Sindh, some years later after annexing it, into the Bombay Presidency. Distance from the provincial capital, Bombay, led to grievances that Sindh was neglected in contrast to other parts of the Presidency. The merger of Sindh into Punjab province was considered from time to time but was turned down because of British disagreement and Sindhi opposition, both from Muslims and Hindus, to being annexed to Punjab.[122]

The British desired to increase their profitability from Sindh and carried out extensive work on the irrigation system in Sindh, for example, the Jamrao Canal project. However, the local Sindhis were described as both eager and lazy and for this reason, the British authorities encouraged the immigration of Punjabi peasants into Sindh as they were deemed more hard-working. Punjabi migrations to Sindh paralleled the further development of Sindh's irrigation system in the early 20th century. Sindhi apprehension of a ‘Punjabi invasion’ grew.[122]

In his backdrop, desire for a separate administrative status for Sindh grew. At the annual session of the Indian National Congress in 1913, a Sindhi Hindu put forward the demand for Sindh's separation from the Bombay Presidency on the grounds of Sindh's unique cultural character. This reflected the desire of Sindh's predominantly Hindu commercial class to free itself from competing with the more powerful Bombay's business interests.[122] Meanwhile, Sindhi politics was characterised in the 1920s by the growing importance of Karachi and the Khilafat Movement.[123] A number of Sindhi pirs, descendants of Sufi saints who had proselytised in Sindh, joined the Khilafat Movement, which propagated the protection of the Ottoman Caliphate, and those pirs who did not join the movement found a decline in their following.[124] The pirs generated huge support for the Khilafat cause in Sindh.[125] Sindh came to be at the forefront of the Khilafat Movement.[126]

Although Sindh had a cleaner record of communal harmony than other parts of India, the province's Muslim elite and emerging Muslim middle class demanded separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency as a safeguard for their own interests. In this campaign, local Sindhi Muslims identified ‘Hindu’ with Bombay instead of Sindh. Sindhi Hindus were seen as representing the interests of Bombay instead of the majority of Sindhi Muslims. Sindhi Hindus, for the most part, opposed the separation of Sindh from Bombay.[122] Although Sindh had a culture of religious syncretism, communal harmony and tolerance due to Sindh's strong Sufi culture in which both Sindhi Muslims and Sindhi Hindus partook,[127] both the Muslim landed elite, waderas, and the Hindu commercial elements, banias, collaborated in oppressing the predominantly Muslim peasantry of Sindh who were economically exploited.[128] Sindhi Muslims eventually demanded the separation of Sindh from the Bombay Presidency, a move opposed by Sindhi Hindus.[129][130][131]

In Sindh's first provincial election after its separation from Bombay in 1936, economic interests were an essential factor of politics informed by religious and cultural issues.[132] Due to British policies, much land in Sindh was transferred from Muslim to Hindu hands over the decades.[133] Religious tensions rose in Sindh over the Sukkur Manzilgah issue where Muslims and Hindus disputed over an abandoned mosque in proximity to an area sacred to Hindus. The Sindh Muslim League exploited the issue and agitated for the return of the mosque to Muslims. Consequentially, a thousand members of the Muslim League were imprisoned. Eventually, due to panic the government restored the mosque to Muslims.[132] The separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency triggered Sindhi Muslim nationalists to support the Pakistan Movement. Even while the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province were ruled by parties hostile to the Muslim League, Sindh remained loyal to Jinnah.[134] Although the prominent Sindhi Muslim nationalist G.M. Syed left the All India Muslim League in the mid-1940s and his relationship with Jinnah never improved, the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims supported the creation of Pakistan, seeing in it their deliverance.[123] Sindhi support for the Pakistan Movement arose from the desire of the Sindhi Muslim business class to drive out their Hindu competitors.[135] The Muslim League's rise to becoming the party with the strongest support in Sindh was in large part linked to its winning over of the religious pir families.[136] Although the Muslim League had previously fared poorly in the 1937 elections in Sindh, when local Sindhi Muslim parties won more seats,[137] the Muslim League's cultivation of support from local pirs in 1946 helped it gain a foothold in the province,[138] it didn't take long for the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims to campaign for the creation of Pakistan.[139][140]

Partition (1947)

In 1947, violence did not constitute a major part of the Sindhi partition experience, unlike in Punjab. There were very few incidents of violence on Sindh, in part due to the Sufi-influenced culture of religious tolerance and in part that Sindh was not divided and was instead made part of Pakistan in its entirety. Sindhi Hindus who left generally did so out of a fear of persecution, rather than persecution itself, because of the arrival of Muslim refugees from India. Sindhi Hindus differentiated between the local Sindhi Muslims and the migrant Muslims from India. A large number of Sindhi Hindus travelled to India by sea, to the ports of Bombay, Porbandar, Veraval, and Okha.[141]

See also

Notes

- These covered carnelian products, seal carving, work in copper, bronze, lead, and tin.[14]

- Brooke (2014), p. 296. "The story in Harappan India was somewhat different (see Figure 111.3). The Bronze Age village and urban societies of the Indus Valley are some-thing of an anomaly, in that archaeologists have found little indication of local defense and regional warfare. It would seem that the bountiful monsoon rainfall of the Early to Mid-Holocene had forged a condition of plenty for all, and that competitive energies were channeled into commerce rather than conflict. Scholars have long argued that these rains shaped the origins of the urban Harappan societies, which emerged from Neolithic villages around 2600 BC. It now appears that this rainfall began to slowly taper off in the third millennium, at just the point that the Harappan cities began to develop. Thus it seems that this "first urbanisation" in South Asia was the initial response of the Indus Valley peoples to the beginning of Late Holocene aridification. These cities were maintained for 300 to 400 years and then gradually abandoned as the Harappan peoples resettled in scattered villages in the eastern range of their territories, into the Punjab and the Ganges Valley....' 17 (footnote):

(a) Giosan et al. (2012);

(b) Ponton et al. (2012);

(c) Rashid et al. (2011);

(d) Madella & Fuller (2006);

Compare with the very different interpretations in

(e) Possehl (2002), pp. 237–245

(f) Staubwasser et al. (2003) - The end-date arrived as a result of equating Sindhu with the Sin tu kingdom, described in the Great Tang Records on the Western Regions during 641 A.D. Modern scholars reject this claim.

- Diwaji and Sahiras were respectively Toramana and Mihirakula. Rai Sahasi was held to be Tegin Shah, Rai Sahiras II to be Vasudeva, and Rai Sahasi II, an anonymous successor.

- This descent from Mauryas was proposed on the basis of Rai Mahrit, then ruler of Chittor claiming to be Sahasi II's brother. Rulers of pre-Sisodia Rajasthan usually claimed a descent from Mauryas and this identification went perfectly with Xuanzang's noting the King of Sin-tu to be a Sudra.

References

- Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 257–259. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- Quddus, Syed Abdul (1992). Sindh, the Land of Indus Civilisation. Royal Book Company. ISBN 978-969-407-131-2.

- JPRS Report: Near East & South Asia. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 1992.

- "Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List (Pakistan)". UNESCO. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- Choudhary Rahmat Ali (28 January 1933). "Now or Never. Are we to live or perish forever?".

- S. M. Ikram (1 January 1995). Indian Muslims and partition of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-81-7156-374-6. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Phiroze Vasunia 2013, p. 6.

- Southworth, Franklin. The Reconstruction of Prehistoric South Asian Language Contact (1990) p. 228

- Burrow, T. Dravidian Etymology Dictionary Archived 1 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine p. 227

- "Sindh, not Sind". The Express Tribune. Web Desk. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- Sanyal, Sanjeev (10 July 2013). Land of the seven rivers : a brief history of India's geography. ISBN 978-0-14-342093-4. OCLC 855957425.

- "Mohenjo-Daro: An Ancient Indus Valley Metropolis".

- "Mohenjo Daro: Could this ancient city be lost forever?". BBC News. 26 June 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Wright 2009, pp. 115–125.

- Dyson 2018, p. 29 "Mohenjo-daro and Harappa may each have contained between 30,000 and 60,000 people (perhaps more in the former case). Water transport was crucial for the provisioning of these and other cities. That said, the vast majority of people lived in rural areas. At the height of the Indus valley civilization the subcontinent may have contained 4-6 million people."

- McIntosh 2008, p. 387: "The enormous potential of the greater Indus region offered scope for huge population increase; by the end of the Mature Harappan period, the Harappans are estimated to have numbered somewhere between 1 and 5 million, probably well below the region's carrying capacity."

- Raychaudhuri, Hemchandra (1953). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of Gupta Dynasty. University of Calcutta. p. 197.

- Jain 1974, p. 209-210.

- Sikdar 1964, p. 501-502.

- H.C. Raychaudhuri (1923). Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. University of Calcutta. ISBN 978-1-4400-5272-9.

- M. A. Dandamaev. "A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire" p 147. BRILL, 1989 ISBN 978-9004091726

- Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing, 2011, p. 33 ISBN 0875868592

- "Hidus could be the areas of Sindh, or Taxila and West Punjab." in Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 2002. p. 204. ISBN 9780521228046.

- Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville, A Geographical Illustration of the Map of India, Translated by William Herbert, London, 1759, p.19; "Tatta est non seulement un ville, mais encore une province de l'Inde, selon les voyageurs modernes. La ville ainsi nommée a pris la place de l'ancienne Patala ou Pattala, qui donnoit autrefois le nom à terrain renfermé entre les bouches de l’Indus." Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville, Eclaircissements géographiques sur la carte de l'Inde, Paris, Imprimerie Royale, 1753, p.39. D'Anville, Orbis Veteribus Notus

- Alexander Burnes, Travels into Bokhara: Containing the Narrative of a Voyage on the Indus, London, Murray, 1839, Vol.I, p.27. William Robertson, An Historical Disquisition concerning Ancient India, Basel, Tourneisen, 1792, pp.20: “Patala (the modern Tatta)”; p.40: “Pattala (now Tatta).” William Vincent, The Commerce and Navigation of the Ancients in the Indian Ocean, London, Cadell and Davies, 1807, p.138. “Tatta, the Páttala of the ancients.” Cf. M. Nisard, Pomponius Méla, oeuvres complètes, Paris, Dubochet et Le Chevalier, 1850, p.656: "Cette région [Patalène], qui tirait son nom de Patala, sa principale ville, est comprise aujourd'hui dans ce qu'on appelle le Sindh y, qui avait autrefois pour capitale Tatta, ville de douze à quinze mille âmes, qui occupe l'emplacement de l'antique Patala".

- Dani 1981, p. 37.

- Eggermont 1975, p. 13.

- A.H. Dani and P. Bernard, “Alexander and His Successors in Central Asia”, in János Harmatta, B.N. Puri and G.F. Etemadi (editors), History of civilizations of Central Asia (Paris, UNESCO, 1994) II: 85. Herbert Wilhelmy has pointed out that siltation had caused the Indus to change its course many times over the centuries and that in Alexander’s time it bifurcated at the site of Bahmanabad, 75 kilometres to the north east of Hyderabad, which John Watson McCrindle had considered to occupy the site of ancient Patala: Herbert Wilhelmy, “Verschollene Städte im Indusdelta“, Geographische Zeitschrift, 56: 4 (1968): 256-294, n.b. 258-63; McCrindle (1901): 19, 40, 124, 188; idem, The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great, Westminster, Constable, 1893, pp.356-7.

- Thorpe 2009, p. 33.

- Rengel, Marian (15 December 2003). Pakistan: A Primary Source Cultural Guide. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. pp. 59–62. ISBN 978-0-8239-4001-1. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- "Buddhism In Pakistan". pakteahouse.net. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 773. ISBN 9780691157863. Archived from the original on 15 January 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2023.

- Chandwani, Nikhil (13 March 2019). "History of Hinduism in Sindh from ancient times and why Sindh belongs to India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 13 March 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

Hinduism was majorly practiced in Sindh during this time but with the entry of Chandragupta Maurya in 313 BC there was an entry of Buddhism as well. .... However, there was a revival of Hindu religion during the Gupta period which then became dominated culture in Sindh. It flourished well all over India, especially in the Sindh region. .... Before the invasion of Mohammed bin Qasim, Hinduism was the most prominent religion in Sindh that constituted about 64 percent of percent of the total population.

- "The Greeks... took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis." Strabo 11.11.1 (Strabo 11.11.1)

- Rawlinson, H. G. (2001). Intercourse Between India and the Western World: From the Earliest Times of the Fall of Rome. Asian Educational Services. p. 114. ISBN 978-81-206-1549-6.

- The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians

- Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, 38

- Indian Art - Volume 2, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala, Prithivi Prakashan, 1977, Page 43

- Indian Art of the Gupta Age: From Pre-classical Roots to the Emergence of Medieval Trends, Editors Śrīrāma Goyala, Śaṅkara Goyala, Kusumanjali Book World, 2000, p. 85

- Vakataka - Gupta Age Circa 200-550 A.D., Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Anant Sadashiv Altekar, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1967, p. 435

- Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval "Hindu-Muslim" Encounter, Finbarr Barry Flood, Princeton University Press, 2009, p. 50

- South Asian Archaeology 1975: Papers from the Third International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe Held in Paris, J. E. Van Lohuizen-De Leeuw BRILL, 1979. The image of the Brahma from Mirpur Khas is on the cover. link

- Gupta Dynasty – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009.

- Harle, James C. (January 1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- Relief Panel: 5th century - 6th Century from Mirpur Khas Pakistan, Victoria & Albert Museum, UK

- MacLean, Derryl N. (1989). Religion and Society in Arab Sind. E.J. Brill. pp. 53–60, 71 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0.

- Schastok, S.L. (1985). The Śāmalājī Sculptures and 6th Century Art in Western India. Brill. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-90-04-06941-1.

- MacLean, Derryl N. (1989). Religion and Society in Arab Sind. E.J. Brill. pp. 7–20 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0.

- Indian Art. Prince of Wales Museum of Western India. 27 September 1964. pp. 2–4.

- Gopal, Navjeevan (3 May 2019). "In ancient Punjab, religion was fluid, not watertight, says Romila Thapar". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

...but after the Gupta period, Buddhism began to decline.

- Fogelin, Lars (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780199948239. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

the emergence and spread of Hinduism through Indian society helped lead to Buddhism's gradual decline in India.

- Schindel, Nikolaus; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj; Pendleton, Elizabeth (2016). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: adaptation and expansion. Oxbow Books. pp. 126–129. ISBN 9781785702105.

- Senior, R.C. (2012). "Some unpublished ancient coins" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society Newsletter. 170 (Winter): 17.

- Senior, R.C. (1991). "The Coinage of Sind from 250 AD up to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society. 129 (June–July 1991): 3–4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 17. ISBN 9780857716668.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 18. ISBN 9780857716668.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9781474400305.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 145, map XIV.1 (i). ISBN 0226742210.

- Wink, Andre (1996). Al Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL. pp. 133, 152–153. ISBN 90-04-09249-8.

- Mirchandani, B. D. (1985). Glimpses of Ancient Sind: A Collection of Historical Papers. Sindh: Saraswati M. Gulrajani. pp. 25, 53–56.

- Asif (2016), pp. 65, 81–82, 131–134

- Krishnamoorthy, K. (1982). Banabhatta (Sanskrit Writer). Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-7201-674-6.

- Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 146, map XIV.2 (b). ISBN 0226742210.

- Wink, André (1991). Al- Hind: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest. 2. BRILL. pp. 152–153. ISBN 9004095098.

- Rao, B. S. L. Hanumantha; Rao, K. Basaveswara (1958). Indian History and Culture. Commercial Literature Company. p. 337.

- Omvedt, Gail (18 August 2003). Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste. SAGE Publications. p. 160. ISBN 9780761996644. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

It appears that at the time of Hsuan Tsang, after a millennia-long historical con- flict, Brahmanism had emerged dominant. Buddhism was declining and it would, within centuries, vanish from the land of its origin.

- Mumtaz, Khawar; Mitha, Yameena; Tahira, Bilquis (2003). Pakistan: Tradition and Change. Oxfam. p. 12. ISBN 9780855984960. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

By the seventh century AD, Buddhism declined completely and Hinduism became the dominant religion. Around this time the Arabs, who had trade and commerce links going back for centuries, came for the first time as conquerors (712 AD). By 724 AD they had established direct rule in Sindh.

- Malik, Jamal (31 October 2008). Islam in South Asia: A Short History. E.J. Brill. p. 40. ISBN 9789047441816. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

Sind's majority population followed Hindu traditions but a substantial minority was Buddhist.

- MacLean, Derryl N. (1989). Religion and Society in Arab Sind. E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

As a result, it is possible to conclude that Buddhism, while important in Sindh, was not the only or even the majority religion. Hindus were definitely in the vast majority in upper Sind (where, as noted, there were few if any Buddhists), but probably at least equal in numbers to the Buddhists in Lower Sindh and Mukrân. (page 52) ..... Nevertheless, the data indicate, in a general way, the relative balance between the two religions in Lower Sind and the predominance of Hinduism in Upper Sind. (page 72)

- Avari, Burjor (2013). Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A History of Muslim Power and Presence in the Indian Subcontinent. Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 9780415580618. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

It is quite likely therefore that some form of Buddhist collaboration with the Arabs may have begun even before the Arab invasion.

- Sarao, K.T.S. (October 2017). "Buddhist-Muslim Encounter in Sind During the Eighth Century". Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute. JSTOR. 77: 77. JSTOR 26609161. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

The primary sources indicate that the Buddhists tended to collaborate with the invading Arabs at an early date

- Siddiqi, Iqtidar Husain (2010). Indo-Persian Historiography Up to the Thirteenth Century. Primus Books. p. 34. ISBN 9788190891806. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

At the time of the Arab invasion, the Buddhists repudiated their allegiance to Dahir and decided to cooperate with his enemy.

- Maclean, Derryl N. (1 December 1989). Religion And Society In Arab Sind. E.J. Brill. p. 121-122. ISBN 9789004085510. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

Buddhists tended to collaborate to a significantly greater extent and at an earlier date than did Hindus.... Where the primary sources refer to religious affiliation, Buddhist conmunities (as opposed to individuals) are always (there is no exception) mentioned in terms of collaboration.... Furthermore, Buddhists generally collaborated early in the campaign before the major conquest of Sind had been achieved and even before the conquest of towns in which they were resident and which were held by strong garrisons.

- Gankovsky, Yu. V.; Gavrilov, Igor (1973). "The Peoples of Pakistan: An Ethnic History". Nauka Publishing House. p. 116-117. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

....the invasion of Sind was all the easier because the leaders of the Buddhist community were in opposition to the Hindu rulers and sympathized with the Arabic [sic] invaders and sometimes even helped them.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (May 1999). Rethinking India's Oral and Classical Epics: Draupadi Among Rajputs, Muslims, and Dalits. University of Chicago Press. p. 281. ISBN 9780226340500. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

While the results of Buddhist collaboration in Sind were short-lived, the history of Hinduism there continued in multiple forms, first with Brahman-led resistance continuing in upper Sind around Multan...

- Vijaya Ramaswamy, ed. (2017). Migrations in Medieval and Early Colonial India. Routledge. ISBN 9781351558242. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2012), The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, p. 602, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- "History of India". indiansaga.com. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2012), The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, pp. 601–2, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1976), Readings in political history of India, ancient, mediaeval, and modern, B.R. Pub. Corp., on behalf of Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies, p. 216

- Tripathi 1967, p. 337.

- Asif 2016, p. 35.

- Wink 2002, p. 203.

- The Classical age, by R. C. Majumdar, p. 456

- Asif 2016, p. 117.

- Suvorova, Anna (2004), Muslim Saints of South Asia: The Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries, Routledge, p. 218, ISBN 978-1-134-37006-1

- P. M. ( Nagendra Kumar Singh), Muslim Kingship in India, Anmol Publications, 1999, ISBN 81-261-0436-8, ISBN 978-81-261-0436-9 pg 43-45.

- P. M. ( Derryl N. Maclean), Religion and society in Arab Sindh, Published by Brill, 1989, ISBN 90-04-08551-3, ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0 pg 140-143.

- A Gazetteer of the Province of Sindh. G. Bell and Sons. 1874.

- Abdulla, Ahmed (1987). An Observation: Perspective of Pakistan. Tanzeem Publishers.

- Habib, Irfan (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2007). History of Pakistan: Pakistan through ages. Sang-e Meel Publications. p. 218. ISBN 978-969-35-2020-0.

But as many kings of the dynasty bore Hindu names, it is almost certain that the Soomras were of local origin. Sometimes they are connected with Paramara Rajputs, but of this there is no definite proof.

- Siddiqui, Habibullah. "The Soomras of Sindh: their origin, main characteristics and rule – an overview (general survey) (1025 – 1351 AD)" (PDF). Literary Conference on Soomra Period in Sindh.

- "The Arab Conquest". International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. 36 (1): 91. 2007.

The Soomras are believed to be Parmar Rajputs found even today in Rajasthan, Saurashtra, Kutch and Sindh. The Cambridge History of India refers to the Soomras as "a Rajput dynasty the later members of which accepted Islam" (p. 54 ).

- Collinet, Annabelle (2008). "Chronology of Sehwan Sharif through Ceramics (The Islamic Period)". In Boivin, Michel (ed.). Sindh through history and representations : French contributions to Sindhi studies. Karachi: Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 11, 113 (note 43). ISBN 978-0-19-547503-6.

- Boivin, Michel (2008). "Shivaite Cults And Sufi Centres: A Reappraisal Of The Medieval Legacy In Sindh". In Boivin, Michel (ed.). Sindh through history and representations : French contributions to Sindhi studies. Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-547503-6.

- Aniruddha Ray (4 March 2019). The Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526): Polity, Economy, Society and Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 43–. ISBN 978-1-00-000729-9.

- "Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta".

- Census Organization (Pakistan); Abdul Latif (1976). Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Larkana. Manager of Publications.

- Rapson, Edward James; Haig, Sir Wolseley; Burn, Sir Richard; Dodwell, Henry (1965). The Cambridge History of India: Turks and Afghans, edited by W. Haig. Chand. p. 518.

- U. M. Chokshi; M. R. Trivedi (1989). Gujarat State Gazetteer. Director, Government Print., Stationery and Publications, Gujarat State. p. 274.

It was the conquest of Kutch by the Sindhi tribe of Sama Rajputs that marked the emergence of Kutch as a separate kingdom in the 14th century.

- Directions in the History and Archaeology of Sindh by M. H. Panhwar

- Archnet.org: Thattah Archived 2012-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Census Organization (Pakistan); Abdul Latif (1976). Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Larkana. Manager of Publications.

- Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Jacobabad

- Davies, p. 627

- Bosworth, "New Islamic Dynasties," p. 329

- The Travels of Marco Polo - Complete (Mobi Classics) By Marco Polo, Rustichello of Pisa, Henry Yule (Translator)

- Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia by Nicholas Tarling p.39. ISBN 9780521663700.

- "Hispania [Publicaciones periódicas]. Volume 74, Number 3, September 1991 – Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes". cervantesvirtual.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Brohī, ʻAlī Aḥmad (1998). The Temple of Sun God: Relics of the Past. Sangam Publications. p. 175.

Kalhoras a local Sindhi tribe of Channa origin...

- Burton, Sir Richard Francis (1851). Sindh, and the Races that Inhabit the Valley of the Indus. W. H. Allen. p. 410.

Kalhoras...were originally Channa Sindhis , and therefore converted Hindoos.

- Verkaaik, Oskar (2004). Migrants and Militants: Fun and Urban Violence in Pakistan. Princeton University Press. pp. 94, 99. ISBN 978-0-69111-709-6.

The area of the Hindu-built mansion Pakka Qila was built in 1768 by the Kalhora kings, a local dynasty of Arab origin that ruled Sindh independently from the decaying Moghul Empire beginning in the mid-eighteenth century.

- Ansari 1992, pp. 32–34.

- Sarah F. D. Ansari (31 January 1992). Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0.

- "History of Khairpur and the royal Talpurs of Sindh". Daily Times. 21 April 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- Solomon, R. V.; Bond, J. W. (2006). Indian States: A Biographical, Historical, and Administrative Survey. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1965-4.

- Baloch, Inayatullah (1987). The Problem of "Greater Baluchistan": A Study of Baluch Nationalism. Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden. p. 121. ISBN 9783515049993.

- Ziad, Waleed (2021). Hidden Caliphate: Sufi Saints Beyond the Oxus and Indus. Harvard University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780674248816.

- "The Royal Talpurs of Sindh - Historical Background". www.talpur.org. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- General Napier apocryphally reported his conquest of the province to his superiors with the one-word message peccavi, a schoolgirl's pun recorded in Punch (magazine) relying on the Latin word's meaning, "I have sinned", homophonous to "I have Sindh". Eugene Ehrlich, Nil Desperandum: A Dictionary of Latin Tags and Useful Phrases [Original title: Amo, Amas, Amat and More], BCA 1992 [1985], p. 175.

- Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015), State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security, Routledge, pp. 102–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- I. Malik (3 June 1999), Islam, Nationalism and the West: Issues of Identity in Pakistan, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 56–, ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0

- Gail Minault (1982), The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India, Columbia University Press, pp. 105–, ISBN 978-0-231-05072-2

- Ansari 1992, p. 77

- Pakistan Historical Society (2007), Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, Pakistan Historical Society., p. 245

- Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 775, doi:10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- Ayesha Jalal (4 January 2002). Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850. Routledge. pp. 415–. ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0.

- Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4.

- Pakistan Historical Society (2007). Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. Pakistan Historical Society. p. 245.

- Ansari, p. 77.

- Jalal 2002, p. 415

- Amritjit Singh; Nalini Iyer; Rahul K. Gairola (15 June 2016), Revisiting India's Partition: New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics, Lexington Books, pp. 127–, ISBN 978-1-4985-3105-4

- Khaled Ahmed (18 August 2016), Sleepwalking to Surrender: Dealing with Terrorism in Pakistan, Penguin Books Limited, pp. 230–, ISBN 978-93-86057-62-4

- Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003), Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises, SAGE Publications, pp. 138–, ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5

- Ansari, p. 115.

- Ansari 1992, p. 115.

- Ansari 1992, p. 122.

- I. Malik (3 June 1999). Islam, Nationalism and the West: Issues of Identity in Pakistan. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0.

- Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003). Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises. SAGE Publications. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5.

- Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 776-777, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

Sources

- Ansari, Sarah F. D. (1992), Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0

- Asif, Manan Ahmed (2016), A Book of Conquest, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-66011-3

- Brooke, John L. (2014). Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87164-8.

- Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (2003), Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts, and Historical Issues, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-7824-143-2

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002), History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D., Atlantic Publishers & Dist, ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5

- Dani, A.H. (1981). "Sindhu – Sauvira : A glimpse into the early history of Sind". In Khuhro, Hamida (ed.). Sind through the centuries : proceedings of an international seminar held in Karachi in Spring 1975. Karachi: Oxford University Press. pp. 35–42. ISBN 978-0-19-577250-0.

- Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

- Eggermont, Pierre Herman Leonard (1975). Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahmin Town of Harmatelia. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-6186-037-2.

- Giosan L, Clift PD, Macklin MG, Fuller DQ, et al. (2012). "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (26): E1688–E1694. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109E1688G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3387054. PMID 22645375.

- Jain, Kailash Chand (1974). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-0-8426-0738-4.

- Jalal, Ayesha (4 January 2002), Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0

- Madella, Marco; Fuller, Dorian Q. (2006). "Palaeoecology and the Harappan Civilisation of South Asia: a reconsideration". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (11–12): 1283–1301. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.1283M. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.10.012. ISSN 0277-3791.

- McIntosh, Jane (2008). The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2.

- Panikkar, K. M. (1964) [first published 1947], A Survey of Indian History, Asia Publishing House

- Phiroze Vasunia (16 May 2013). The Classics and Colonial India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-01-9920-323-9.

- Ponton, Camilo; Giosan, Liviu; Eglinton, Tim I.; Fuller, Dorian Q.; et al. (2012). "Holocene aridification of India" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (3). L03704. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..39.3704P. doi:10.1029/2011GL050722. hdl:1912/5100. ISSN 0094-8276.

- Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-1642-9.

- Puri, Baij Nath (1986). The History of the Gurjara-Pratiharas. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

- Rashid, Harunur; England, Emily; Thompson, Lonnie; Polyak, Leonid (2011). "Late Glacial to Holocene Indian Summer Monsoon Variability Based upon Sediment Records Taken from the Bay of Bengal" (PDF). Terrestrial, Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. 22 (2): 215–228. Bibcode:2011TAOS...22..215R. doi:10.3319/TAO.2010.09.17.02(TibXS). ISSN 1017-0839.

- Sikdar, Jogendra Chandra (1964). Studies in the Bhagawatīsūtra. Muzaffarpur, Bihar, India: Research Institute of Prakrit, Jainology & Ahimsa. pp. 388–464.

- Singh, Mohinder, ed. (1988), History and Culture of Panjab, Atlantic Publishers & Distri, GGKEY:JB4N751DFNN

- Staubwasser, M.; Sirocko, F.; Grootes, P. M.; Segl, M. (2003). "Climate change at the 4.2 ka BP termination of the Indus valley civilization and Holocene south Asian monsoon variability". Geophysical Research Letters. 30 (8): 1425. Bibcode:2003GeoRL..30.1425S. doi:10.1029/2002GL016822. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 129178112.

- Thorpe, Showick Thorpe Edgar (2009), The Pearson General Studies Manual 2009, 1/e, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-2133-9

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1967), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2

- Wink, André (2002), Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7Th-11th Centuries, BRILL, ISBN 0-391-04173-8

- Wright, Rita P. (2009). The Ancient Indus: Urbanism, Economy, and Society. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57219-4. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Wynbrandt, James (2009), A Brief History of Pakistan, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-6184-6

_mint._Dated_AH_97_(AD_715-6).jpg.webp)