Takasaki

Takasaki (高崎市, Takasaki-shi, [takasakiɕi]) is a city located in Gunma Prefecture, Japan. As of 31 August 2020, the city had an estimated population of 372,369 in 167,345 households,[1] and a population density of 810 persons per km². The total area of the city is 459.16 square kilometres (177.28 sq mi). Takasaki is famous as the hometown of the Daruma doll, theoretically representing the Buddhist sage Bodhidharma and in modern practice a symbol of good luck. Takasaki has been the largest city in Gunma Prefecture since 1990 after beating Maebashi.

Takasaki

高崎市 | |

|---|---|

![Left: Takasaki Kannon Statue [ja], Takasaki Castle, Gunma Music Center [ja], Right: Mount Haruna and Lake Haruna, Takasaki Daruma Doll (all items from above to bottom)](../I/Takasaki_Montage.jpg.webp) Left: Takasaki Kannon Statue, Takasaki Castle, Gunma Music Center, Right: Mount Haruna and Lake Haruna, Takasaki Daruma Doll (all items from above to bottom) | |

Flag  Seal | |

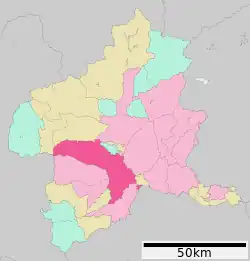

Location of Takasaki in Gunma Prefecture | |

| |

Takasaki | |

| Coordinates: 36°19′18.8″N 139°0′11.8″E | |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Kantō |

| Prefecture | Gunma |

| First official recorded | late 5th century AD (official) |

| City settled | April 1, 1900 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kenji Tomioka (since May 2011) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 459.16 km2 (177.28 sq mi) |

| Population (August 31, 2020) | |

| • Total | 372,369 |

| • Density | 810/km2 (2,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| Phone number | 027-321-111 |

| Address | Takamatsu-cho 35-1, Takasaki-shi, Gunma-ken 370-8501 |

| Climate | Cwa |

| Website | Official website |

| Symbols | |

| Bird | Japanese bush-warbler |

| Flower | Sakura |

| Tree | Zelkova serrata, Cyclobalanopsis |

Geography

Takasaki is located in the southwestern part of Gunma Prefecture in the flat northwestern part of the Kantō Plain. The city is located approximately 90 to 100 kilometers from central Tokyo . Mount Akagi, Mount Haruna and Mount Myogi can be seen from the city, and the southern slopes of Mount Haruna are within the city limits. The Tone River, Karasu River and Usui River flow through the city. Although Takasaki is located over 100 kilometers from the coast, much of the city is low-lying, and the elevation of the city hall and central city area is only 97 meters above sea level. The land rises to the northern and western parts of the city to a maximum elevation of 1690 meters.

Surrounding municipalities

Climate

Takasaki has a Humid continental climate (Köppen Cwa) characterized by warm summers and cold, windy winters (karakkaze) with occasional snowfall. The average annual temperature in Takasaki is 14.0 °C (57.2 °F). The average annual rainfall is 1,354.9 mm (53.34 in), with September as the wettest month. The temperatures are highest on average in August, at around 25.8 °C (78.4 °F), and lowest in January, at around 2.6 °C (36.7 °F).[2]

| Climate data for Kamisatomi, Takasaki (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1977−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.1 (68.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

27.9 (82.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

35.6 (96.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

40.3 (104.5) |

38.9 (102.0) |

38.8 (101.8) |

32.1 (89.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

40.3 (104.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.8 (56.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.0 (86.0) |

31.2 (88.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.6 (52.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.8 (78.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.9 (40.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16.7 (62.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

8.9 (48.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.0 (15.8) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 29.1 (1.15) |

26.8 (1.06) |

61.0 (2.40) |

78.9 (3.11) |

112.2 (4.42) |

173.1 (6.81) |

221.4 (8.72) |

221.6 (8.72) |

214.2 (8.43) |

147.7 (5.81) |

45.4 (1.79) |

23.6 (0.93) |

1,354.9 (53.34) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 3.5 | 4.1 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 14.2 | 16.0 | 14.4 | 13.2 | 10.1 | 5.8 | 3.9 | 112.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 208.1 | 200.3 | 207.6 | 206.4 | 202.7 | 140.7 | 154.2 | 178.3 | 137.4 | 154.4 | 179.4 | 193.6 | 2,163.1 |

| Source 1: Japan Meteorological Agency[3][2] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: 理科年表 | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Per Japanese census data,[4] the population of Takasaki has recently plateaued after a long period of growth.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 244,376 | — |

| 1970 | 280,625 | +14.8% |

| 1980 | 323,403 | +15.2% |

| 1990 | 346,933 | +7.3% |

| 2000 | 358,465 | +3.3% |

| 2010 | 371,302 | +3.6% |

| 2020 | 372,973 | +0.5% |

History

During the Edo period, the area of present-day Takasaki was the center of the Takasaki Domain, a feudal domain held by a branch of the Matsudaira clan under the Tokugawa shogunate in Kōzuke Province. The area also prospered from its location on the Nakasendō highway connecting Edo with Kyoto. Post stations located within the borders of modern Takasaki were: Shinmachi-shuku, Kuragano-shuku, and Takasaki-shuku. Following the Meiji Restoration, Takasaki was briefly capital of Gunma Prefecture, before the capital was moved to Maebashi in 1881.

Takasaki Town was created within Gunma District, Gunma on April 1, 1889 with the creation of the modern municipalities system. It was raised to city status on April 1, 1900. On April 1, 1927, Takasaki annexed the neighboring villages of Tsukasawa and Kataoka, followed by Sano on October 1, 1937. The city largely escaped damage in World War II. Following the war, it continued to expand its borders by annexing the village of Rokugo on April 1, 1951, Shintakao and Nakamura as well as Yawata and Toyooka from Ushi District on January 20, 1955. This was followed by Orui village and Sano village from Tano District on September 30, 1956. The city celebrated its 360th anniversary in 1963 and annexed the town of Kuragano on March 31 of the same year. On September 1, 1965 the village of Gunnan was annexed.

In September 1987, five-year-old Yoshiaki Ogiwara, the son of a local firefighter, was abducted and subsequently murdered in Takasaki. The murder received heavy media coverage across Japan.[5]

On April 1, 2001 Takasaki was proclaimed a Special City (Tokurei-shi), which gave it greater autonomy.

On January 23, 2006, the towns of Gunma, Kurabuchi and Misato (all from Gunma District), and the town of Shinmachi (from Tano District) were merged into Takasaki. On October 1, 2006, the town of Haruna (from Gunma District) was merged into the expanded city of Takasaki. Gunma District was dissolved as a result of this merger. On June 1, 2009, the town of Yoshii (from Tano District) was merged into expanded city of Takasaki.[6]

Takasaki was elevated to a Core city with even greater autonomy on April 1, 2011.

Government

Takasaki has a mayor-council form of government with a directly elected mayor and a unicameral city council of 38 members. Takasaki contributes nine members to the Gunma Prefectural Assembly. In terms of national politics, the city is divided between the Gunma 4th district and Gunma 5th district of the lower house of the Diet of Japan.

Successive mayors

| Period | Mayor | Term start | Term end |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hachirō Yajima | July 18, 1900 | July 16, 1906 |

| 2 | Ubuzawa Ichitarō | July 20, 1906 | October 9, 1908 |

| 3-4 | Nobuyasu Uchida | November 5, 1908 | November 4, 1918 |

| 5 | Shūtarō Furuki | February 3, 1919 | July 22, 1921 |

| 6 | Zenji Tsuchiya | September1, 1921 | August 31, 1925 |

| 7 | Tōru Aoki | January 9, 1926 | January 8, 1930 |

| 8 | Tetsukichirō Kanayama | March 3, 1930 | April 26, 1930 |

| 9 | Saksaburō Sekine | May 10, 1930 | August 21, 1932 |

| 10 | Ichizō Yamaura | August 29, 1932 | August 28, 1936 |

| 11-13 | Munetarō Kubota | September 11, 1936 | November 15, 1946 |

| 14-15 | Hirokazu Kojima | April 10, 1947 | May 1, 1955 |

| 16-19 | Keizaburō Sumitani | May 2, 1955 | May 1, 1971 |

| 20-23 | Kenji Numaga | May 2, 1971 | May 1, 1987 |

| 24-29 | Yukio Matsuura | May 2, 1987 | May 1, 2011 |

| 30-33 | Kenji Tomioka | May 2, 2011 | ongoing |

Source:Takasaki City

Economy

Takasaki is a regional commercial center and transportation hub, and is a major industrial center within Gunma Prefecture. Companies headquartered in Takasaki include CUSCO Japan, an automotive parts manufacturer, and Yamada Denki, a home appliance retailer.

Education

Universities and colleges

- Takasaki City University of Economics

- Takasaki University of Commerce

- Takasaki University of Health and Welfare

- Gumma Paz College

- Jobu University

- Ikuei Junior College

- Takasaki University of Health and Welfare Junior College

- Takasaki University of Commerce Junior College

- Niijima Gakuen Junior College

Primary and secondary education

Takasaki has over sixty public elementary schools and 25 public middle schools operated by the city government and eight public high schools operated by the Gunma Prefecture Board of Education. In addition, the city operates one public high school and there are five private high schools. The prefecture also operates five special education schools for the handicapped.

English education

Takasaki developed its own unique English curriculum and implemented it at all of the primary and middle schools in the city.[7] Primary school students in 1st through 4th grades have English lessons (formally called 'foreign language activities') once a week, while 5th and 6th grades have proper English lessons twice a week. This totals 35 hours (only 34 for 1st grade) of English education for 1st through 4th graders and 70 hours for 5th and 6h graders.[7]

The main emphasis on primary school English in Takasaki is communication; students are actively encouraged to listen to authentic English and express themselves to their peers. In order to achieve this, Mayor Tomioka pushed to increase the number of Assistant Language Teachers in the city.[7][8] Commonly referred to as ALTs, they are native English speakers hired from abroad to come and assist Japanese teachers during English class. Takasaki employs many ALTs through The JET Program.[9] Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Takasaki had at least 1 ALT assigned to every primary and middle school in the city. The Takasaki Board of Education claims that Takasaki was the first in all of Japan to have English lessons starting in 1st grade, to have English twice a week for older students, and to assign at least 1 ALT to every school.[10]

In 2014, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (also abbreviated as MEXT) acknowledged the need to increase students' English ability in order to succeed globally.[11] In 2016, MEXT then designated Takasaki as a pilot city to test out upcoming changes to the nationwide English curriculum; the changes were modeled after the existing Takasaki curriculum. It was decided that the changes would officially begin in stages; primary schools would adapt the new curriculum nationwide in 2020, middle schools in 2021, and secondary schools in 2022.[12][11]

In 2019, MEXT did a survey to see how both primary and middle school students were performing in all subjects at the prefectural level. It was found that students in Gunma Prefecture placed in the top 6 prefectures across all subjects, and for the first time tied with Tokyo for first place in English.[10]

Transportation

Railway

![]() JR East – Hokuriku Shinkansen

JR East – Hokuriku Shinkansen

![]() JR East – Jōetsu Shinkansen

JR East – Jōetsu Shinkansen

![]() JR East – Takasaki Line, Shōnan-Shinjuku Line, Ueno-Tokyo Line

JR East – Takasaki Line, Shōnan-Shinjuku Line, Ueno-Tokyo Line

Highway

Kan-etsu Expressway – Takasaki-Tamamura Smart Interchange – Takasaki Junction – Takasaki Interchange – Maebashi Interchange

Kan-etsu Expressway – Takasaki-Tamamura Smart Interchange – Takasaki Junction – Takasaki Interchange – Maebashi Interchange Jōshin-etsu Expressway – Yoshii Interchange

Jōshin-etsu Expressway – Yoshii Interchange Kita-Kantō Expressway – Takasaki Junction

Kita-Kantō Expressway – Takasaki Junction National Route 17

National Route 17 National Route 18

National Route 18 National Route 254

National Route 254 National Route 354

National Route 354 National Route 406

National Route 406

Local attractions

- Takasaki Castle

- Mount Haruna

- Lake Haruna

- Haruna Shrine

- Minowa Castle

- The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma

- The sound of a suikinkutsu in the Suikintei Garden of former Yoshii town is designated as one of the 100 Soundscapes of Japan by the Ministry of the Environment[13]

- Shorinzan Daruma Temple

- Takasaki Byakue Dai-Kannon, the 10th largest Kannon statue in Japan

Events

- Takasaki Festival & Fireworks

- Takasaki Film Festival

- Takasaki Marching Festival

- Kannonyama Candle Festival

King of Pasta

Gunma is one of the leading producers of wheat in all of Japan.[14] As such, dishes that utiliize wheat flour play in important role in local food culture. Takasaki is said to have many pasta shops per capita and in recent years has been called the pasta town.[14][15] Since 2009, Takasaki has held an annual competition called King of Pasta; citizens can buy mini portions of pasta dishes from participating restaurants and vote for the best one.[16]

Sport

- Arte Takasaki - football (soccer) club

Twin towns – sister cities

Battle Creek, Michigan, United States (1981)

Battle Creek, Michigan, United States (1981) Muntinlupa, Metro Manila, Philippines (2006)

Muntinlupa, Metro Manila, Philippines (2006) Plzeň, Czech Republic (1990)

Plzeň, Czech Republic (1990) Santo André, São Paulo, Brazil (1981)

Santo André, São Paulo, Brazil (1981)

Notable people

- Toll Yagami, musician (Buck-Tick)

- Yutaka Higuchi, musician (Buck-Tick)

- Takeo Fukuda, former Prime Minister of Japan

- Yasuo Fukuda, former Prime Minister of Japan

- Kyosuke Himuro, musician (Boøwy)

- Tomoyasu Hotei, musician (Boøwy)

- Fujio Masuoka, inventor of flash memory

- Kanai Mieko (born in Takasaki 1947), writer

- Hirofumi Nakasone, politician

- Yasuhiro Nakasone, former Prime Minister of Japan

- Kiyoshi Ogawa, Imperial Japanese Navy kamikaze pilot

- Hakubun Shimomura, politician

- German architect Bruno Taut lived for some time in Takasaki

- Kenji Tsukagoshi, navigator and aviator

Singaporean actress Jeanette Aw became an official PR ambassador for the city after starring in Ramen Teh, which was set and filmed in Takasaki.

References

- "Takasaki City official statistics" (in Japanese). Japan.

- 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). JMA. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- 観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値). JMA. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- Takasaki population statistics

- Kristof, Nicholas D. "Kidnap-murder of 5-year-old shakes Japan", The New York Times, 20 September 1987. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Information at kokudo.or.jp Archived August 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "4月から小学校全校で英語教育" (in Japanese). 高崎新聞. 25 December 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "令和2年度高崎市総合教育会議 会議録" (PDF). 高崎市の公式HP. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "小学校における英語教育と高崎市の取組" (PDF). 自治体国際化フォーラム|. 自治体国際化 (CLAIR). Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "広報高崎" (PDF). 高崎市の公式HP. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "英語教育改革が2020年度からスタート、小中高校で英語の授業はどう変わる?" (in Japanese). 日本教育新聞電子版 NIKKYOWEB. 26 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "新学習指導要領" (PDF). 公明党の公式HP. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "100 Soundscapes of Japan". Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "パスタのまち高崎". 高崎市の公式HP. Takasaki City. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "高崎市はなぜパスタの街になったのか?|FunLIfeHack". FunLIfeHack (in Japanese). Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "King of Pasta". Official Website for King of Pasta. キングオブパスタ実行委員会. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- "友好都市". city.takasaki.gunma.jp (in Japanese). Takasaki. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

External links

- Official Website (in Japanese)