Bruno Taut

Bruno Julius Florian Taut (4 May 1880 – 24 December 1938) was a renowned German architect, urban planner and author of Prussian Lithuanian heritage ("taut" means "nation" in Lithuanian).[1] He was active during the Weimar period and is known for his theoretical works as well as his building designs.

Bruno Taut | |

|---|---|

Bruno Taut (1910) | |

| Born | 4 May 1880 |

| Died | 24 December 1938 (aged 58) |

| Resting place | Edirnekapı Martyr's Cemetery |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse(s) | Hedwig Wollgast (1879-1968) Erica Wittich (1893 - 1975) |

| Children | Heinrich Taut (1907-1995) Elisabeth Taut (1909-1999) Clarissa Wittich (1918-1998) |

| Relatives | Max Taut (brother) Leopold Ackermann (maternal grandfather) Edmund Ackermann (uncle) |

Early life and career

Taut was born in Königsberg in 1880. After secondary school, he studied at the Baugewerkschule. In the following years, Taut worked in the offices of various architects in Hamburg and Wiesbaden. In 1903, he was employed by Bruno Möhring in Berlin, where he acquainted himself with Jugendstil and new building methods combining steel with masonry. From 1904 to 1908, Taut worked in Stuttgart for Theodor Fischer and studied urban planning. He received his first commission through Fischer in 1906, which involved the renovation of the village church in Unterriexingen.

In 1908, he returned to Berlin to study art history and construction at the Royal Technical Higher School of Charlottenburg (Königlich Technische Hochschule Charlottenburg), now the Technical University of Berlin. A year later, he established the architecture firm Taut & Hoffmann with Franz Hoffmann.

Taut's first large projects came in 1913. He became a committed follower of the Garden City movement, evidenced by his design for the Falkenberg Estate.[2][3]

Taut adopted the futuristic ideals and techniques of the avant-garde as seen in the prismatic dome of the Glass Pavilion, which he built for the association of the German glass industry for the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne. His aim was to make a whole building out of glass instead of merely using glass as a surface or decorative material. He created glass-treaded metal staircases, a waterfall with underlighting, and colored walls of mosaic glass. His sketches for the publication "Alpine Architecture" (1917) are the work of an unabashed utopian visionary, and he is classified as a Modernist and in particular an Expressionist. Much of Taut's literary work in German remains untranslated into English.[2][3]

Germany

In 1910 after training in Berlin, working for Theodor Fischer's firm in Stuttgart, and establishing his own firm in Berlin, the experienced architect Hermann Muthesius suggested that Taut visit England to learn the garden city philosophy. Muthesius also introduced him to some of the Deutscher Werkbund group of architects, including Walter Gropius. Taut had socialist sympathies, and before World War I this hindered his advancement.

Taut's practical activity changed with World War I. He became a pacifist and so avoided military service. He began to write and sketch, less to escape from the brutalities of war than to present a positive utopia in opposition to this reality. Taut designed an immense circular garden city with a radius of about 7 km (4.3 mi) for three million inhabitants. The "City Crown" was to be in the very center. "Mighty and inaccessible", it would have been the culmination of a community and cultural center, a skyscraper-like, purpose-free "crystal building". "The building contains nothing but one beautiful room which can be reached by either of two staircases to the right and to the left of the theatre and the little community center. How can I even begin to describe what it is only possible to construct!", said Taut of the City Crown.[2]

Taut completed two housing projects in Magdeburg from 1912 through 1915, which were influenced directly by the humane functionalism and urban design solutions of the garden city philosophy. The reform estate, created for a housing trust, was built in 1912–15 in the southwest of Magdeburg. The estate consists of one-story terrace houses and was the first project in which Taut used colour as a design principle. The construction of the estate was continued by Carl Krayl. Taut served as a city architect in Magdeburg from 1921 to 1923. During his time a few residential developments were built, one of which was the Hermann Beims estate (1925–28) with 2,100 apartments. Taut designed the exhibition hall City and Countryside in 1921 with concrete trusses and a central skylight.

A lifelong painter, Taut was distinguished from his European modernist contemporaries by his devotion to color. As in Magdeburg, he applied lively, clashing colors to his first major commission, the 1912 Gartenstadt Falkenberg housing estate in Berlin, which became known as the "Paint Box Estates". The 1914 Glass Pavilion, an illustration of the new possibilities of glass, was also brightly colored. The difference between Taut and his Modernist contemporaries was never more obvious than at the 1927 Weissenhofsiedlung housing exhibition in Stuttgart. In contrast to the pure-white entries from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius, Taut's house (Number 19) was painted in primary colors. Le Corbusier is reported to have exclaimed, "My God, Taut is colour-blind!"[4]

During the November Revolution of 1918, Taut was involved in the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, an association of revolutionary artists based on council democracy. The group assumed the "primacy of architecture", demanded the demolition of all war memorials and saw art as a means of revolutionizing society. From March 1919, Taut belonged to their three-man management team, along with Adolf Behne, César Klein and Walter Gropius. The group disbanded in 1921.[5]

In 1924 Taut was made chief architect of GEHAG, a Berlin public housing cooperative, and was the main designer of several successful large residential developments ("Gross-Siedlungen") in Berlin, notably the 1925 Hufeisensiedlung ("Horseshoe Estate"), named for its configuration around a pond, and the 1926 Onkel-Toms-Hütte development ("Uncle Tom's Cabin") in Zehlendorf, named for a local restaurant and set in a thick grove of trees. Both of these constructions became prominent examples of the use of colorful details in architecture.

Taut worked for the city architect of Berlin, Martin Wagner, on some of Berlin's Modernist Housing Estates, now recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The designs featured controversial modern flat roofs; access to sunlight, air, and gardens; and generous amenities like gas, electric light, and bathrooms. Political conservatives complained that these developments were too opulent for 'simple people'. The progressive Berlin mayor, Gustav Böss, defended them: "We want to bring the lower levels of society higher."

Between 1924 and 1931, Taut's team completed more than 12,000 dwellings. In tribute to Taut, GEHAG incorporated an abstracted graphic of the Horseshoe Estate in its logo. This state housing association was sold by the Senate of Berlin in 1998; its legal successor is Deutsche Wohnen.

Japan

Being of liberal political sympathies, Taut fled Germany when the Nazis gained power.[6] He was promised work in the USSR in 1932 and 1933 but was obliged to return to Germany in February 1933 to a hostile political environment.

Later in the same year, Taut fled to Switzerland. Then, with an invitation from Japanese architect Isaburo Ueno, he traveled to Japan via France, Greece, Turkey and Vladivostok, arriving in Tsuruga, Japan, on May 3, 1933.[7] Taut made his home in Takasaki, Gunma, where he produced three influential book-length appreciations of Japanese culture and architecture, comparing the historical simplicity of Japanese architecture with modernist discipline. For a time Taut worked as an industrial design teacher, and his models of lamps and furniture sold at the Miratiss shop in Tokyo.[8]

Taut was noted for his appreciation of the stark, minimalist vein of Japanese architecture found at the Ise Shrine and the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto. He was the first to write extensively about the architectural features of the Katsura Imperial Villa from a modernist perspective. Contrasting it with the elaborately decorated shrines of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu at Nikkō, Tochigi, he famously said that "Japan's architectural arts could not rise higher than Katsura, nor sink lower than Nikko".[9] Taut's writing on the Japanese minimalist aesthetic found an appreciative audience in Japan and subsequently influenced the work of Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius.[10]

The only extant Taut-designed architectural work in Japan is the extension to the Hyuga Villa at Atami in Shizuoka. Built-in 1936 on a site below the original villa owned by businessman Rihei Hyuga, and part modern and part traditional Japanese in style, the three rooms provided additional space for social events and views over nearby Sagami Bay.[11]

Turkey

Offered a position as Professor of Architecture at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul (currently, Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University), Taut relocated to Turkey in 1936. In Ankara he joined other German wartime exiles, including Martin Wagner and Taut's associate Franz Hillinger, who arrived in 1938. Some of Taut's work was received unfavorably, however, and labeled as "cubic". In a letter to a Japanese friend he wrote, "They gave me a great opportunity in that they gave me freedom for my craft. I will make a building that is not 'cubic'; they are calling all modernism cubic. For this building, I am thinking of using some Turkish motifs." He proceeded to design his own house in İstanbul's Ortaköy neighborhood, bridging the architectural traditions of his exile existence. His studio resembled that of the Einstein Tower in Potsdam, while the front view recalled a Japanese pagoda.

After leaving Germany, Taut gradually moved away from modernism. A colleague remarked that "Like everyone who gets old, Taut is stuck with Renaissance principles and cannot find a way towards the new! I am very disappointed... It is a shame for such an avant-gardist."[12]

Before his death in 1938, Taut wrote at least one more book and designed a number of educational buildings in Ankara and Trabzon under commissions from the Turkish Ministry of Education. The most significant of these buildings were the Faculty of Languages, History and Geography at Ankara University, Ankara Atatürk High School and Trabzon High School. His last building project, the Cebeci School, was left unfinished. Taut's final work, one month before his death, was the catafalque that was used for the official state funeral of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on 21 November 1938 in Ankara. It was a simple design, consisting of large wooden columns and a flag that covered the coffin.[12][13]

Taut died on 24 December 1938 and was laid to rest at the Edirnekapı Martyr's Cemetery in Istanbul as its first and only non-Muslim.[14][13]

Bibliography

- Berkovich, Gary. Reclaiming a History. Jewish Architects in Imperial Russia and the USSR. Volume 2. Soviet Avant-garde: 1917–1933. Weimar und Rostock: Grunberg Verlag. 2021. P. 193. ISBN 978-3-933713-63-6

- Bletter, Rosemarie Haag (1983). "Expressionism and the New Objectivity". Art Journal. 43 (2): 108–120. doi:10.1080/00043249.1983.10792213. JSTOR 776647.

- Bletter, Rosemarie Haag (1981). "The Interpretation of the Glass Dream—Expressionist Architecture and the History of the Crystal Metaphor". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 40 (1): 20–43. doi:10.2307/989612. JSTOR 989612.

- Jose-Manuel Garcia Roig, Tres arquitectos alemanes: Bruno Taut. Hugo Häring. Martin Wagner Universidad de Valladolid: 2004. ISBN 978-84-8448-288-8.

- Matthias Schirren (2004): Bruno Taut: Alpine Architecture: A Utopia, Prestel Publishing (bilingual edition) ISBN 978-3-7913-3156-0

- Iain Boyd Whyte (2010): Bruno Taut and the Architecture of Activism (Cambridge Urban and Architectural Studies), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-13183-4

- Deutscher Werkbund, Winfried Brenne (2008): Bruno Taut: Master of colorful architecture in Berlin, Verlagshaus Braun, ISBN 978-3-935455-82-4

- Markus Breitschmid (2012): "The Architect as 'Molder of the Sensibilities of the General Public'": Bruno Taut and his Architekturprogramm, in: The Art of Social Critique. Painting Mirrors of Social Life, Shawn Chandler Bingham (ed.) Lanham: Lexington Books of Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 155–179, ISBN 978-0-7391-4923-2

- Markus Breitschmid (2017): "Glass House at Cologne." in: Harry Francis Mallgrave, David Leatherbarrow, Alexander Eisenschmidt (eds.) The Companions to the History of Architecture, Volume IV, Twentieth-Century Architecture, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., London, 2017, ISBN 978-1-444-33851-5, pp. 61–72.

- Markus Breitschmid (2017): "Alpine Architecture - Bruno Taut", in: Disegno - Quarterly Journal for Design, No. 14, London, pp. 62–70.

- A Comparative Study On The Works of German Expatriate Architects In Their Home-Land And In Turkey During The Period of 1927-1950 / Yüksel Zandel Pöğün / IYTE

- Architectural Theory / Edited by Harry Francis Mallgrave and Christina Contandriopoulos

- Architectural Theory From The Renaıssance to The Present / Bernd Evers

- Modern ve Sürgün – Almanca Konuşan Ülkelerin Mimarları Türkiye’de / Yüksel Zandel Pöğün

Gallery

Horseshoe Estate (Hufeisensiedlung), built in 1925, in Britz, Berlin

Horseshoe Estate (Hufeisensiedlung), built in 1925, in Britz, Berlin Worpsweder Käseglocke, built in 1926

Worpsweder Käseglocke, built in 1926 Bruno Taut, "Red Front" building, Horseshoe Estate, Britz, Berlin

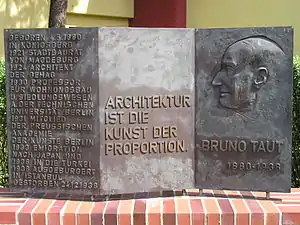

Bruno Taut, "Red Front" building, Horseshoe Estate, Britz, Berlin Monument to Taut at the Uncle Tom's Cabin Estate, Berlin-Zehlendorf

Monument to Taut at the Uncle Tom's Cabin Estate, Berlin-Zehlendorf Faculty of Languages, History and Geography of Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey

Faculty of Languages, History and Geography of Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey Interior design of the private accommodation "Tautes Heim" located in the Hufeisensiedlung, Berlin-Britz

Interior design of the private accommodation "Tautes Heim" located in the Hufeisensiedlung, Berlin-Britz Hermann Gieseler Gymnasium, interior, Magdeburg, Taut and John Göderitz

Hermann Gieseler Gymnasium, interior, Magdeburg, Taut and John Göderitz

References

- "Nomen est omen". Monumente. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- Architectural Theory / Edited by Harry Francis Mallgrave and Christina Contandriopoulos

- Architectural Theory From The Renaıssance to The Present / Bernd Evers

- Kirch, K., The Weissenhofsiedlung Rizzoli International Publications, 1989

- "Bruno Taut, Program of the "Arbeitsrat für Kunst" (1918)". ghdi.ghi-dc.org. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- "Turkey's Jewish Past". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- Denoon, Donald (2001). Multicultural Japan: Paleolithic to Postmodern (Paperback ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 0-521-00362-8.

- Cabeza-Latinez, Jose Maria (2014). Weber, Willi (ed.). Lessons from Vernacular Architecture. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: earthscan, Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-84407-600-0.

- Varley, H. Paul (1995). Hume, Nancy (ed.). Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader - Culture in the Present Age. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 321. ISBN 0-7914-2399-9.

- "Katsura Imperial Villa I Architecture I Phaidon Store". Phaidon. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- "Hyuga Villa Visitor Information". Atami City Official Website. Atami City, Shizuoka. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- Modern ve Sürgün – Almanca Konuşan Ülkelerin Mimarları Türkiye’de / Yüksel Zandel Pöğün

- A Comparative Study On The Works of German Expatriate Architects In Their Home-Land And In Turkey During The Period of 1927-1950 / Yüksel Zandel Pöğün / IYTE

- Newspaper Hürriyet- En İyi On/Bruno Taut Villası (in Turkish)

External links

- Bruno Taut at archINFORM

- Britz/Hufeisensiedlung in Berlin by Bruno Taut & Martin Wagner (with drawings and photos)

- Museum of Architecture biography of Taut