Sonnet 35

William Shakespeare's Sonnet 35 is part of the Fair Youth sequence, commonly agreed to be addressed to a young man; more narrowly, it is part of a sequence running from 33 to 42, in which the speaker considers a sin committed against him by the young man, which the speaker struggles to forgive.

| Sonnet 35 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

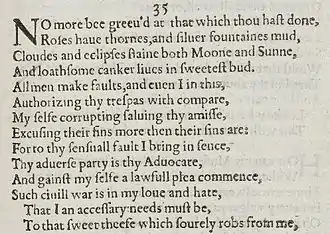

Sonnet 35 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 35 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has fourteen lines, divided into three quatrains and a final rhyming couplet. It follows the form's rhyme scheme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is written in a type of metre called iambic pentameter based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. Line four exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter

× / × / × / × / × / And loathsome canker lives in sweetest bud. (35.4)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Two seemingly unmetrical lines can be explained by the Elizabethan pronunciations authórizing (line 6) and áccessary (line 13).[2]

Source and analysis

C. Knox Pooler notes that line 4 echoes a simile in The Two Gentlemen of Verona that was derived from Plutarch; Stephen Booth notes several adaptations of proverbs, applied against one another in a manner that tends to reinforce the contradictory emotions of the speaker. Fleay perceived an allusion to Elizabeth in the "moon" of line 3, and to Southampton in the "bud" of line 4.

The poem is among the better-known and more frequently anthologized of the sonnets. It is commonly regarded as exemplary of Shakespeare's skill at evoking ambivalence and at creating complex personae. L. C. Knights regarded the first quatrain as typically Elizabethan, but praises the phonic and syntactic complexity of the second quatrain. As Booth writes, "The facts the poem reports should make the speaker seem admirable in a reader's eyes; the speaker's manner, however, gives conviction to the idea that he is worthy of the contempt he says he deserves" (192).

Lines 7 and 8 are sometimes seen as a crux, and are universally recognized as ambiguous. Knights notes the potential doubleness of line 7, either "I corrupt myself by excusing you" or "I myself corrupt you more by forgiving you." George Steevens glosses 8: "Making the excuse more than proportioned to the offence", while Bullen has it "Making this excuse: Their sins are more than thine." Both Bullen and Steevens amended the quarto's "their" to "thy," as is now standard practice.

Further analysis

In Sonnet 35, one of the most apparent points that critics have addressed is the duality of the poem's tone. The first quatrain describes what at first appears to be praise and is followed by the second quatrain, in which the speaker addresses a lover's sin and the corruption of himself as a result. Stephen Booth draws attention to the discrepancies between the first and second quatrains and remedies this discrepancy by explaining the speaker's true purpose in the first quatrain. He says, "This sonnet is a variation of Shakespeare's habits of damning with fulsome praise and of making flattering accusations."[3] The speaker lists sarcastic praises, which are supposed to be read as if the speaker was recalling these excuses he made for his sinful lover with contempt. Quatrain 2 creates "a competition in guilt between the speaker and the beloved."[3] The competition grows with the speaker's attempt to justify his sin of becoming the accomplice by degrading the beloved. This leads to an escalation in quatrain 3, where the speaker declares his inner turmoil. He says, "Such civil war is in my love and hate." This conflict within the speaker leads to the couplet, which according to Booth declares the "beloved diminished under a new guilt of being the beneficiary of the speaker's ostentatious sacrifice."[3] In summation, Booth's reaction to Sonnet 35 is that "the facts the poem reports should make the speaker seem admirable in a reader's eyes; the speaker's manner, however, gives conviction to the idea that he is worthy of the contempt he says he deserves."[4]

Contrary to Booth's take on the duality of Sonnet 35, Helen Vendler claims the dedoublement is most visible "in the violent departure from in quatrain 1 in the knotted language of quatrain 2."[3] Instead of describing the speaker as divided over love and hate, she says that the speaker in quatrain 1 is "misguided, and even corrupt, according to the speaker of quatrain 2."[3] She also disagrees with Booth's reading of the couplet. Rather, she related the contrasting voices in the first and second quatrain to a philosophical metaphor for the self. I have corrupted myself is a statement that presupposes a true "higher self which has, by a lower self, been corrupted, and which should once again take control. Even the metaphor of the lawsuits implies that one side in each suit is 'lawful' and should win."[5]

Vendler brings up another point of criticism, which is the confessional aspect of Sonnet 35. Shakespeare uses the vocabulary of legal confession. In an essay by Katherine Craik she discusses the connection between this sonnet and the early criminal confession. Craik says, "the speaker testifies against the unspecified 'trespass' of a 'sweet thief', but simultaneously confesses to playing 'accessory' to the robbery."[6] The speaker also excuses the beloved's sin, which brought about his "wrongful self-incrimination" in the sonnet. She concludes, "Fault can be transferred in the act of confessing, and judgments are clouded rather than clarified."[6] Her conclusion aligns with Booth's claim that the speaker is an unlikeable one. It also aligns with Vendler's point that either the speaker or the beloved must be wrong. Craik's essay draws the conclusion that the speaker is actually at greater fault than the beloved.

Homosexuality in Shakespeare's Sonnet 35

Sonnet 35 deals with the speaker being angry with the young man for an apparent betrayal through infidelity. The apparent homoeroticism between the speaker and the young man has spurred debates about the sexuality of the speaker and consequently Shakespeare himself. There are 3 main points to discuss with this issue: the problem of ambiguity in the writing, the possibility of applying an anachronistic view of love and consequently mistaking these sonnets homoerotic, and finally the implications of Shakespeare's life and homosexual tendencies.

- The ambiguity of the texts

Paul Hammond argues the difficulty in pinning down the sexual language lies in the intentional ambiguity. First, one must keep in mind that in the early modern period the death penalty was still in effect for sodomy, so it was extremely important that writers remain vague to protect their own lives. Keeping the language ambiguous enabled multiple interpretations of the writings without the danger of being branded as homosexual.[7] What is more, the words we would use to describe homosexual behavior is either anachronistic to the time period or it carried different meanings. For example, there is no seventeenth-century equivalent word for homosexual. Additionally, "sodomy" and "sodomite" in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have a radically different meaning than modern perceptions. It is not clear if sodomy even had any specific representation of sexual behavior between men. It could be used for sexual activity between men, women, or either sex and an animal. It can also be used as a rhetorical device to establish the unacceptable foreignness of an enemy.[7]

To further confuse things, even the meaning of "friend" is subject to scrutiny. "Friend" can be used to greet a complete stranger, it can mean someone of the same sex that is an extremely close friend, and it can even be used to describe a man and a woman in love.[7] In the same respect, lover can be meant to have sexual connotations or just imply a strong platonic friendship. Hammond states, "The words 'love', 'lover', and 'friend' in the Sonnets have no single or unambiguous meanings, but are continually being redefined, refelt, reimagined."[7] He also states, "Sometimes indications of sexual desire are present not in the form of metaphor or simile, but as a cross-hatching of sexually charged vocabulary across the surface of a poem whose attention seems to lie elsewhere."[7]

- Misinterpretation of love

Carl D. Atkins argues that readers are misinterpreting the type of love depicted in the sonnets as homosexual. He believes that we must look at it with an eye that considers the concepts of love in Shakespeare's time. He sees the relationship between the speaker and the young man as a passionate friendship that is more pure than heterosexual relationships and in some cases can even take precedence over marriage.[4] He puts an emphasis in distinguishing between intellectual lover, or love of the mind, and animal love, or love of the body. The sonnets are writing about a pure platonic form of love and modern readers are injecting too much sexual politics into his or her criticism. Atkins sees the sonnets more as a chronicle of underlying emotions experienced by lovers of all kinds whether it is heterosexual, homosexual or passionate friendship: adoration, longing, jealousy, disappointment, grief, reconciliation, and understanding.[4]

- Homosexual implications for Shakespeare's life

Stephen Booth considers the sonnets in the context of Shakespeare's personal sexuality. First, he discusses the dedication of sonnets 1-126 to "Mr. W. H." Booth considers Henry Wriothesley, third Earl of Southampton, and William Herbert, third Earl of Pembroke as the best candidates. Both men work with the idea that the sonnets are being addressed to a man of high rank and both were considered to be attractive.[8] However, the dedication remains mostly a mystery. Some theories even point to the dedication being to Shakespeare himself.[8]

In regards to the sonnets having a bearing on Shakespeare’s sexuality, Booth maintains the sonnets are written as a form of fiction. He believes the hermaphroditic sexual innuendos are being overanalyzed and misinterpreted to point towards Shakespeare's own sexuality. In reality, it was commonplace for sexual wordplay to switch between genders. He writes, "Moreover, Shakespeare makes overt rhetorical capital from the fact that the conventions he works in and the purpose for which he uses them do not mesh and from the fact that his beloveds are not what the sonnet conventions presume them to be."[8] Booth maintains that sonnets involving wooing a man are in fact an attempt of Shakespeare to exploit the conventions of sonnet writing. Overall, Booth asserts that the sexual undercurrents of the sonnets are of the sonnets and do not say anything about the sexuality of Shakespeare.[8]

Interpretations

- Keb' Mo', for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

- Sting references the first quatrain in the lyrics of his song Consider Me Gone.

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Groves (2013), p. 167.

- Engle, Lars (2007).

- Atkins, Carl D. (2007).

- Vendler, Helen (1997).

- Craik, Katherine A. (2002).

Related article: . - Hammond, Paul. (2002).

- Booth, Stephen (1977).

References

- Atkins, Carl D. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets with Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Rosemont, Madison.

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Craik, Katherine A. (2002). Shakespeare's A Lover's Complaint and Early Modern Criminal Confession. Shakespeare Quarterly. The Folger Shakespeare Library.

- Engle, Lars (2007). William Empson and the Sonnets: A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnets. Blackwell Limited, Malden.

- Groves, Peter (2013). Rhythm and Meaning in Shakespeare: A Guide for Readers and Actors. Melbourne: Monash University Publishing. ISBN 978-1-921867-81-1.

- Hammond, Paul (2002). Figuring Sex Between Men from Shakespeare to Rochester. Clarendon, New York.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Knights, L. C. (1967). Shakespeare's Sonnets: Elizabethan Poetry. Paul Alpers. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Lopez, Jeremy (2005). Sonnet 35. Greenwood Companion to Shakespeare. pp. 1136–1140.

- Matz, Robert (2008). The World of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Introduction. Jefferson, N.C., McFarland & Co..

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 35 at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 35 at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

.png.webp)