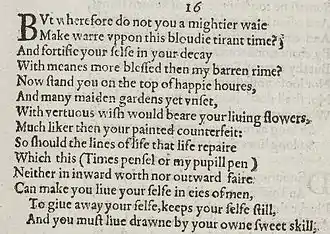

Sonnet 16

Sonnet 16 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is among those sonnets referred to as the procreation sonnets, within the Fair Youth sequence.

| Sonnet 16 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

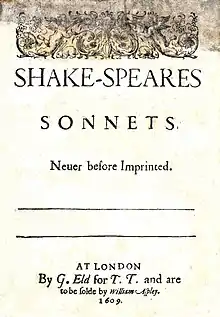

Sonnets 16 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Although the previous sonnet, Sonnet 15, does not overtly discuss procreation, Sonnet 16 opens with "But..." and goes on to make the encouragement clear. The two poems form a diptych. In Sonnet 16, the speaker asks the young man why he does not actively fight against time and age by having a child.

Structure

Sonnet 16 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. This type of sonnet consists of three quatrains followed by a couplet. It follows the English sonnet's typical rhyme scheme: ABAB CDCD EFG EFG. The sonnet is written in iambic pentameter, a type of metre in which each line is based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The fifth line exhibits a regular iambic pattern:

× / × / × / × / × / Now stand you on the top of happy hours, (16.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Alternatively, "hours" (and its rhyme "flowers") may be scanned as two-syllable words, giving lines five and seven final extrametrical syllables or feminine endings.

Synopsis and analysis

Sonnet 16 asks why the youth doesn't strive more forcefully ("a mightier way") to wage war against "this bloody tyrant time?" Why, the poet continues, doesn't the youth take precautions as he declines ("fortify your self in your decay") by some more fruitful ("blessed") means than the poet's own sterile efforts ("barren rhyme")?

The poet pictures the youth standing "on the top of happy hours", the time when the stars or the wheel of fortune blessed an individual. There, since the "happy hour" was used of both nuptials and childbirth, the youth controls the moment when he might beget children, as well as his destiny. On this note, a "maiden garden" is a womb yet to be made fruitful. To "set" a garden was to 'sow' it (compare Sonnet 15 where it is used of grafting) so that it can give birth to the youth's "living flowers," self-generated new copies.[2]

Interpretation of the sonnet is said to hinge on the third quatrain (lines 9-12), which is generally regarded as obscure. Edmond Malone suggested that "lines of life" refers to children, with a pun on line as bloodline. This reading was accepted by Edward Dowden and others.[3] Also, "repair" can mean to make anew or newly father (re + père), which may be relevant. But as well, "lines of life" can mean the length of life, or the fate-lines found on the hand and face read by fortune-tellers. An artistic metaphor also arises in this sonnet, and "lines" can be read in this context.[2]

Line 10 is the source of some dissent amongst scholars. One reading is that, compared to his physical offspring (“this”), the depictions of time's pencil or the poet's novice pen ("pupil") are ineffectual. But it is the potential insight into the sonnets' chronology, through the relationship of "this" to "Time's pencil" and "my pupil pen", that is the focus of the debate: George Steevens regards the words as evidence Shakespeare wrote his sonnets as a youth; for T. W. Baldwin the phrase connects this sonnet to The Rape of Lucrece.[4] While in general terms "Time" is in this line a form of artist (rather than a destroyer, as elsewhere in the cycle), its exact function is unclear. In Shakespeare's time, a pencil was both a small painter's brush and a tool to engrave letters, although graphite pencils bound in wax, string or even wood were known in the 16th century.[2]

Following William Empson, Stephen Booth points out that all of the potential readings of the disputed lines, in particular the third quatrain, are potentially accurate: while the lines do not establish a single meaning, the reader understands in general terms the usual theme, the contrast between artistic and genealogical immortality.[5][6] The assertion is that procreation is a more viable route to immortality than the "counterfeit" of art.

The sonnet concludes with resignation that the efforts of both time and the poet to depict the youth's beauty cannot bring the youth to life ("can make you live") in the eyes of men (compare the claim in Sonnet 81, line 8, "When you entombed in men's eyes shall lie"). By giving himself away in sexual union, or in marriage ("give away your self") the youth will paradoxically continue to preserve himself ("keeps your self still"). Continuing both the metaphor of pencils and lines, as well as the fatherly metaphor and that of fortune, the youth's lineage must be delineated ("drawn") by his own creative skill ("your own sweet skill").

References

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 16". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- Dowden, Edward (1881). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Baldwin, T.W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Empson, William (1975). Seven Types of Ambiguity. New York: Vintage.

- Booth, Stephen (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Further reading

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485. — Volume I and Volume II at the Internet Archive

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. Arden Shakespeare, third series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951. — 1st edition at the Internet Archive

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 16 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 16 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

.png.webp)