Smoked salmon

Smoked salmon is a preparation of salmon, typically a fillet that has been cured and hot or cold smoked.

Due to its moderately high price, smoked salmon is considered a delicacy. Although the term lox is sometimes applied to smoked salmon, they are different products.[1]

Presentation

Smoked salmon is a popular ingredient in canapés, often combined with cream cheese and lemon juice.

In New York City and Philadelphia and other cities of North America, smoked salmon is known as "nova" after the sources in Nova Scotia, and is likely to be sliced very thinly and served on bagels with cream cheese or with sliced red onion, lemon and capers. In Pacific Northwest cuisine of the United States and Canada, smoked salmon may also be fillets or nuggets, including hickory or alder-smoked varieties and candied salmon (smoked and honey, or sugar-glazed, also known as "Indian candy").

In Europe, smoked salmon may be found thinly sliced or in thicker fillets, or sold as chopped "scraps" for use in cooking. It is often used in pâtés, quiches and pasta sauces. Scrambled eggs with smoked salmon mixed in is another popular dish. Smoked salmon salad is a strong-flavored salad, with ingredients such as iceberg lettuce, boiled eggs, tomato, olives, capers and leeks, and with flavored yogurt as a condiment.

Slices of smoked salmon are a popular appetizer in Europe, usually served with some kind of bread. In the United Kingdom they are typically eaten with brown bread and a squeeze of lemon. In Germany they are eaten on toast or black bread.

In Jewish cuisine, heavily salted salmon is called lox and is usually eaten on a bagel with cream cheese.[2] Lox is often smoked.

Smoked salmon is sometimes used in sushi, though not widely in Japan; it is more likely to be encountered in North American sushi bars. The Philly Roll combines smoked salmon and cream cheese and rolls these in rice and nori.

History

Smoking is used to preserve salmon against microorganism spoilage.[3] During the process of smoking salmon the fish is cured and partially dehydrated, which impedes the activity of bacteria.[4] An important example of this is Clostridium botulinum, which can be present in seafood,[5] and which is killed by the high heat treatment which occurs during the smoking process.

Smoked salmon has featured in many Native American cultures for a long time. Smoked salmon was also a common dish in Greek and Roman culture throughout history, often being eaten at large gatherings and celebrations.[3] During the Middle Ages, smoked salmon became part of people's diet and was consumed in soups and salads.[3] The first smoking factory was from Poland in the 7th century A.D.[4] The 19th century marked the rise of the American smoked salmon industry in the West Coast, processing Pacific salmon from Alaska and Oregon.[3]

Nutrition

Salmon is a fish with high fat content and smoked salmon is a good source of omega-3 fatty acids including docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA).[6][7] Smoked salmon has a high sodium content due to the salt added during brining and curing.[7] 3 ounces (85 g) of smoked salmon contains approximately 660 mg of sodium, while an equivalent portion of fresh cooked salmon contains about 50 mg.[7] Although high salt content prevents the growth of microorganisms in smoked salmon by limiting water activity,[7] the American Heart Association recommends limiting sodium consumption.[8]

Smoked foods, including smoked salmon also contain nitrates and nitrites which are by-products of the smoking process.[8] Nitrites and nitrates can be converted into nitrosamines, some of which are carcinogenic.[8] However, smoked salmon is not a major source of nitrosamine exposure to humans.[9]

Salt replacement

Studies have been conducted in which some of the sodium chloride used in smoking salmon had been replaced by potassium chloride. The study found that up to one third of the sodium chloride can be replaced by potassium chloride without changing the sensory properties of the smoked salmon.[10] Although potassium chloride has a bitter and metallic taste, the saltiness of the smoked salmon might have masked its undesirable flavor.[10]

| Nutrient | Quantity per portion |

Percentage daily value |

|---|---|---|

| Energy | 120–140 kcals | |

| Energy from fat | 60 kcals | |

| Total fat | 6g | 9% |

| Saturated fat | 3g | 15% |

| Cholesterol | 40 mg | 13% |

| Sodium | 430 mg | 18% |

| Total Carbohydrates | 1g | 0% |

| Protein | 12g | 23% |

| Vitamin A | Trace | 2% |

| Vitamin C | Trace | 0% |

| Calcium | 11 mg | 0% |

| Iron | 0.85 mg | 3% |

| Sodium | 784 mg | |

| Potassium | 175 mg |

*Based on a 2,000 calorie diet – Serving size: about 3 oz or 85 g, cooked.

Production

In the Atlantic basin all smoked salmon comes from the Atlantic salmon, much of it farmed in Norway, Scotland, Ireland and the east coast of Canada (particularly in the Bay of Fundy). In the Pacific, a variety of salmon species may be used. Because fish farming is prohibited by state law, all of Alaska's salmon species are wild Pacific species. Pacific species of salmon include chinook ("King"), sockeye ("red"), coho ("silver"), chum ("keta"), and pink ("humpback").

Cold smoking

Most smoked salmon is cold smoked, typically at 37 °C (99 °F). Cold smoking does not cook the fish, resulting in a delicate texture. Although some smoke houses go for a deliberately 'oaky' style with prolonged exposure to smoke from oak chips, industrial production favours less exposure to smoke and a blander style, using cheaper woods.

Originally, prepared fish were upside hung in lines on racks, or tenters, within the kiln. Workers would climb up and straddle the racks while hanging the individual lines in ascending order. Small circular wood chip fires would be lit at floor level and allowed to smoke slowly throughout the night. The wood fire was damped with sawdust to create smoke; this was constantly tended as naked flames would cook the fish rather than smoke it. The required duration of smoking has always been gauged by a skilled or 'master smoker' who manually checks for optimum smoking conditions.

Smoked salmon was introduced into the UK from Eastern Europe. Jewish immigrants from Russia and Poland brought the technique of salmon smoking to London's east End, where they settled, in the late 19th century. They smoked salmon as way to preserve it as refrigeration was very basic. In the early years, they were not aware that there was a salmon native to the UK so they imported Baltic salmon in barrels of salt water. However, having discovered the wild Scottish salmon coming down to the fish market at Billingsgate each summer, they started smoking these fish instead. The smoking process has changed over the years and many contemporary smokehouses have left the traditional methods using brick kilns behind in favour of commercial methods. Only a handful of traditional smokehouses remain such as John Ross Jr (Aberdeen) Ltd and the Stornoway Smokehouse in the Outer Hebrides. The oldest smokehouse in Scotland is the Old Salmon Fish House built on the banks of the River Ugie in 1585, although not at first for smoking.[11] The oldest smokehouse in England is the 1760 Old Smokehouse in Raglan Street, Lowestoft.[12]

Indigenous peoples in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska have a cold smoking style that is wholly unique, resulting in a dried, "jerky-style" smoked salmon. In the Pacific Northwest this style of salmon has been used for centuries as a primary source of food for numerous indigenous folk. Traditionally smoked salmon has been a staple of north-western American tribes and Canadian First Nations people. To preserve indefinitely in modern times, the fish is typically pressure-cooked.

Hot smoking

Commonly used for both salmon and trout, hot smoking 'cooks' the salmon making it less moist, and firmer, with a less delicate taste. It may be eaten like cold smoked salmon, or mixed with salads or pasta. It is essential to brine the salmon sufficiently and dry the skin enough to form a pellicle prior to smoking. Without a sufficient pellicle, albumin will ooze out of the fish as it cooks, resulting in an unsightly presentation.

Brining salmon

There are three main curing methods that are typically used to cure salmon prior to smoking.

- Wet brining: Brining in a solution containing water, salt, sugar, spices, with (or without) sodium nitrite for a number of hours or days.

- Dry curing: This method is a method often used in Europe, in which salmon fillets are covered with a mix of salt, sugar, and sometimes other spices (traditional London Cure smoked salmon uses salt only). Dry curing tends to be faster than wet brining, as the salt tends to draw out moisture from the fish during the curing process and less drying time is needed in the smokehouse.

- Injection: This is the least typical method as it damages the delicate flesh of salmon. This is the fastest method of all as it injects the curing solution — hence allowing a faster cure throughout the flesh.

The proteins in the fish are modified (denatured) by the salt, which enables the flesh of the salmon to hold moisture better than it would if not brined. In the United States, the addition of salt is regulated by the FDA as it is a major processing aid to ensure the safety of the product. The sugar is hydrophilic, and adds to the moistness of the smoked salmon. Salt and sugar are also preservatives, extending the storage life and freshness of the salmon. Table salt (iodized salt) is not used in any of these methods, as the iodine can impart a dark color and bitter taste to the fish.

Curing

Indian hard smoked salmon is first kippered with salt, sugar and spices and then smoked until hard and jerky-like. See cured salmon. The Scandinavian dish gravlax is cured, but is not smoked.

Packaging

Canning

In British Columbia, canning salmon can be traced back to Alexander Loggie in 1870 who established the first recorded commercial cannery on the Fraser River. Canning soon became the preferred method of preserving salmon in BC growing from three canneries in 1876 to more than ninety by the turn of the century. Sockeye and Pink Salmon make up the majority of canned salmon, with the traditional product containing skin and bones – important sources of calcium and nutrients.[13]

The enzymes of fish operate at an optimum temperature of about 5 °C, the temperature of the water from which they came.[14] Bacteriologically sterile, fish still have a large number of bacteria in their slimy surface and digestive tracts. These bacteria multiply rapidly once the fish dies and start to attack the tissues. The growth of microorganism can greatly affect the quality of the salmon.[14]

The salmon is first dressed and washed, then cut into pieces and filled in cans (previously sterilized) in saline. The cans must then undergo a double steaming process in a vacuum-sealed environment. The steam is pressurized at 121.1 °C for 90 minutes to kill any bacteria. After heating, the cans are cooled under running water, dried and stored in a controlled environment between 10 and 15.5 °C.[14] Before leaving the canneries, they are examined to ensure both the can integrity and safety of the fish.

The Canadian Food and Inspection Agency (CFIA) is responsible for policies, labeling requirements, permitted additives, and inspections for all fish products.[15] All establishments which process fish for export or inter-provincial trade must be registered federally and implement a Quality Management Program (QMP) plan.[15]

Retort pouch

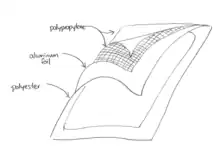

Cooking low-acid food items in a retortable pouch is a relatively new process, with the first commercial use of such retort pouches found in Italy in 1960, Denmark in 1966, and in Japan in 1969.[16] It consists of enclosing the fish in "a multilayer flexible packaging consisting mainly of polypropylene (PP), aluminum foil, and polyester (PET)" instead of the metal can or glass jar used in canning; but from there the technique is quite similar. Four different retort pouch structures were used; namely cast polypropylene (CPP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET)/silicon oxide-coated nylon/CPP (SIOX), Aluminum oxide-coated PET/nylon/CPP (ALOX), and PET/aluminum foil/CPP (FOIL).[17]

Advantages

- Retort pouch salmon minimizes the thermal damage to nutrient, sensory, and other food quality characteristics due to quicker heating based on the thinner package profile when compared to metal cans.[17]

- Pouched food can be eaten without heating, or it can be heated quickly by placing the pouch in boiling water for a few minutes. Frozen foods, in contrast, require heating for about half an hour. Thus, less energy is required for heating a retort pouch. Pouched food can also be heated in a microwave oven simply by removing it from the pouch before heating.[16]

- Compare to cans and glass, it is easier to open and safer.

- Pouch-packed salmon had firmer, more fibrous, drier and chewier texture than that product in a can of equal fill weight.[18]

- Utilising the plastic retort pouch over these other forms, particularly for delicate foods such as smoked salmon. T.D. Durance and L.S. Collins found that "processing of late-run chum salmon in retortable pouches resulted in 48% reduction in processing time" for a given level of lethality to microorganisms,[18] a clear advantage over traditional canning techniques.

Labelling

In the UK, "Scottish smoked salmon" is sometimes used to refer to salmon that is smoked in Scotland but sourced from elsewhere.[19][20] This is despite Food Standards Agency recommendations that such salmon be described as "Salmon smoked in Scotland" instead.[21] Labelling must also include the method of production ('farmed', 'cultivated', 'caught').[22]

Jerky

Smoked salmon jerky is a dehydrated salmon product that is bought ready to eat for consumers and requires no further refrigeration or cooking. (Note there are "fresh" non-heat treated versions made by smaller local producers that require refrigeration.) It is typically made from the trimmings and by-products of salmon products in other smoking facilities.[23] Smoked salmon jerky undergoes the most heat processing of all other smoked salmon products yet still maintains its quality as a good source of omega-3 fatty acids.[24]

Processing

The two main processing techniques for salmon jerky are wet-brining and dry salting. In both cases the salmon is trimmed into narrow slices and then stored cold for less than one day. After being skinned and frozen, if the fish is to undergo the brining method it will require an additional step in which the salmon is left soaking in wet brine (salt solution) for one hour. It is then removed and the excess water is discarded. After this, in both the wet-brining and dry salting method, ingredients such as non-iodized salt, potato starch, or light brown sugar are added.[24] In some smoked salmon jerky products preservatives may also be added to extend the shelf life of the final product.[23] The salmon is then minced with the additives and reformed into thin strips that will be smoked for twenty hours. Between the brining and salting methods for smoked salmon jerky the brining method has been found to leave the salmon more tender with up to double the moisture content of salted jerky. The salmon jerky that undergoes the dry salting method has a tougher texture due to the lower moisture content and water activity. Both forms of salmon jerky still have a much lower moisture content than is found in raw salmon.[24]

Packaging

Smoked salmon jerky is packaged using aseptic packaging to ensure the product is in a sterilized environment. The smoked salmon jerky is commonly packaged in a vacuum sealed bag in which the oxygen has been removed, or in a controlled atmospheric package in which the oxygen has been replaced with nitrogen to inhibit the growth of microorganisms.[25] Because of the high heat nature of which smoked salmon jerky is processed it is a shelf stable product.[26] Depending on the integrity of the packaging and if preservatives were used, smoked salmon jerky may have an approximate shelf-life of six months to one year.[25] Smaller local producers of salmon jerky make a "fresh", non-heat treated product that is not shelf stable.

References

- Kinetz, Erika (22 September 2002). "E. Kinetz. (22 September, 2002). So Pink, So New York. The New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- Jewish Cuisine

- "History Of Smoked Salmon". GourmetFoodStore.com. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Salmon, Verlasso. "The History of Smoked Salmon Verlasso". verlasso.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Lin, Mengshi; Cavinato, Anna G.; Huang, Yiqun; Rasco, Barbara A. (1 January 2003). "Predicting sodium chloride content in commercial king (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) and chum (O. keta) hot smoked salmon fillet portions by short-wavelength near-infrared (SW-NIR) spectroscopy". Food Research International. 36 (8): 761–766. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(03)00070-X.

- "Smoked Salmon Nutrition". GourmetFoodStore.com. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "I enjoy eating smoked salmon. How healthy is it?". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- "Why Should I Limit Sodium?" (PDF). American Heart Association.

- Park, Jong-eun; Seo, Jung-eun; Lee, Jee-yeon; Kwon, Hoonjeong (2015). "Distribution of Seven N-Nitrosamines in Food". Toxicological Research. 31 (3): 279–288. doi:10.5487/tr.2015.31.3.279. PMC 4609975. PMID 26483887.

- Almli, Valérie Lengard; Hersleth, Margrethe (25 November 2012). "Salt replacement and injection salting in smoked salmon evaluated from descriptive and hedonic sensory perspectives". Aquaculture International. 21 (5): 1091–1108. doi:10.1007/s10499-012-9615-4. ISSN 0967-6120. S2CID 6954755.

- "The Old Salmon Fish House". Ugie Salmon. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Historic smokehouse keeps herring tradition alive". East Anglian Daily Times. 27 April 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Canada, Agriculture and Food Trade Commissioner Service;Trade Agreements and Negotiations;International Markets Bureau;Market and Industry Services Branch;Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada;Government of. "Wild Pacific Salmon Overview". agr.gc.ca. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Srilakshmi, B. (2015). Food Science. (3rd ed.). New Delhi, India: New Age International Ltd. pp. 167–168.

- Safety, Government of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Agrifood, Meat and Seafood (2 April 2015). "Quality Management Program". inspection.gc.ca. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lampi, Rauno A. (1 January 1980). "Retort Pouch: The Development of a Basic Packaging Concept in Today's High Technology Era1". Journal of Food Process Engineering. 4 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4530.1980.tb00244.x. ISSN 1745-4530.

- Byun, Youngjae; Bae, Ho Jae; Cooksey, Kay; Whiteside, Scott (1 April 2010). "Comparison of the quality and storage stability of salmon packaged in various retort pouches". LWT - Food Science and Technology. 43 (3): 551–555. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2009.10.001.

- Durance, T.d.; Collins, L.s. (1 September 1991). "Quality Enhancement of Sexually Mature Chum Salmon Oncorhynchus keta in Retort Pouches". Journal of Food Science. 56 (5): 1282–1286. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb04753.x. ISSN 1750-3841.

- Smokin'

- Private Eye #1357, p30

- FSA - Food Origin Labelling accessed 26 November 2007 (PDF)

- "Smoked salmon recipes". BBC Food.

- Kong, Jian (2008). "ProQuest" (Document). ProQuest 304558570.

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help) - Oberholtzer, Ashlan S.; Dougherty, Michael P.; Camire, Mary Ellen (1 August 2011). "Characteristics of Formed Atlantic Salmon Jerky". Journal of Food Science. 76 (6): S396–S400. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02245.x. ISSN 1750-3841. PMID 22417521.

- "Course:FNH200/Lesson 06 - UBC Wiki". wiki.ubc.ca. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Directorate, Government of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Agrifood, Meat and Seafood Safety (6 October 2014). "Guide - Process Control Technical Information". inspection.gc.ca. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)