Simurrum

Simurrum (Akkadian: 𒋛𒈬𒌨𒊑𒅎: Si-mu-ur-ri-im)[1] was an important city state of the Mesopotamian area from around 2000 BCE to 1500 BCE, during the period of the Akkadian Empire down to Ur III. The Simurrum Kingdom disappears from records after the Old Babylonian period.[2] It is thought that in Old Babylonian times its name was Zabban, a notable cult center of Adad.[3][4] It was neighbor and sometimes ally with the Lullubi kingdom.[5]

Kingdom of Simurrum 𒋛𒈬𒌨𒊑𒅎 | |

|---|---|

| 3rd millennium BCE–2nd millennium BCE | |

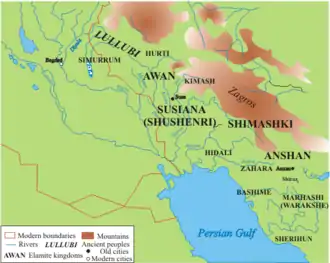

Territory of Simurrum in the Mesopotamia area | |

| Common languages | Akkadian |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Historical era | Early Bronze |

• Established | 3rd millennium BCE |

• Disestablished | 2nd millennium BCE |

| Today part of | Iraq |

History

.jpg.webp)

The Simurrum Kingdom seems to have been part of a belt of Hurrian city states in the northeastern portion of Mesopotamian area.[6][2] They were often in conflict with the rulers of Ur III.[2][7]

Several Kings (𒈗, pronounced Šàr, "Shar", in Akkadian)[8] of Simurrum are known, such as Iddin-Sin and his son Zabazuna.[9][2] Various inscriptions suggest that they were contemporary with king Ishbi-Erra (c. 1953 – c. 1920 BCE).[7] Another king, mentioned in The Great Revolt against Narām-Sîn, was mPu-ut-ti-ma-da-al.[10]

Several inscriptions suggest that Simurrum was quite powerful, and shed some light on the conflicts around the Zagros area, another such example being the Anubanini rock relief of the nearby Lullubi Kingdom.[2] Four inscriptions and a relief (now in the Israel Museum) of the Simurrum have been identified at Bitwata near Ranya in Iraq, and one from Sarpol-e Zahab in Iran.[7][11][12]

The Simurrun were regularly in conflict with the Akkadian Empire. The names of four years of the reign of Sargon of Akkad describe his campaigns against Elam, Mari, Simurrum, and Uru'a (an Elamite city-state):[13][14]

One unknown year during the reign of Akkadian Empire king Naram-Sin of Akkad was recorded as "the Year when Naram-Sin was victorious against Simurrum in Kirasheniwe and took prisoner Baba the governor of Simurrum, and Dubul the ensi (ruler) of Arame".[17][18] Arame is known to be associated with Eshnunna. An Old Babylonian letter also associates Simurrum with Eshnunna. This suggests Simurrum was in the area of that city.[19]

After the Akkadian Empire fell to the Gutians, the Lullubians and the Simurrums rebelled against the Gutian ruler Erridupizir, according to the latter's inscriptions:

Ka-Nisba, king of Simurrum, instigated the people of Simurrum and Lullubi to revolt. Amnili, general of [the enemy Lullubi]... made the land [rebel]... Erridu-pizir, the mighty, king of Gutium and of the four quarters hastened [to confront] him... In a single day he captured the pass of Urbillum at Mount Mummum. Further, he captured Nirishuha.

— Inscription R2:226-7 of Erridupizir.[5]

At one point, Simurrum may have become a vassal of the Gutians.[2]

The Ur III empire was frequently in conflict with the city. A year name of the second ruler, Shulgi, was "Year Simurrum and Lullubum were destroyed for the ninth time". In one of these conflicts Shulgi captured the ruler of Sumurrum, Tabban-darah, and sent him to exile in Drehem. Sillus-Dagan is known to have been a governor of Simurrum under Ur III at the time of ruler Amar-Sin.[20][21] It has been suggested that he was a Amorite.[22] Four texts from Drehem with seals mentioning him have been found, including:

"Sillus-Dagan, governor of Simurrum: Ilak-süqir, son of Alu, the chief administrator,(is) your servant."[23]

During the rule of Su-Sin in the waning years of the Ur III Empire an administrator assigned to build the Mardu Wall reported "When I sent for word (to the area) between the two mountains it was brought to my attention that the Mardu were camped in the mountains. Simurrum had come to their aid. (Therefore) I proceeded to (the area) "between" the mountain range(s) of Ebih in order to do battle".[23]

Military struggles continues up to the time of the final ruler of Ur III, Ibbi-Sin.[24] Simurrum seems to have become independent after the collapse of Ur III.[7]

In order to make peace with a fellow ruler Turukki leader Zaziya (Ur III period) handed over a ruler of Simurrum:

"Zaziya took his children ["grandchildren"] and led them to Zazum of Qutu as hostages (ana yaltiti ... usn). He transported tribute [there]. Zaziya turned him over (ittadinsu) to Zazum of Qutu the king of Simurrum who (once) attended Zazum but had escaped to Zaziya."[25]

Location

It has been proposed that the city was on the Diyala river (which begins as the Sirwan River in Iran).[3]

An early Assyriologist suggested Simurrum was near "Tell 'Ali" which is not far from mouth of the Lower Zab on its left bank and is on the direct line from Assur to Arrapha (Kirkuk), which it is 42 kilometres (26 mi) west of, saying "The region south of Tell 'Ali has never been examined by archaeologists, but seems to contain numerous ruined towns and canals".[26] Twenty five cuneiform tablets from the Middle Assyrian period were found at the site.[27][28]

The site of Qala Shirwana, a large mound 30 metres (98 ft) tall with an additional 10-metre (33 ft) citadel at the top in the southern basin of the Diyala river, on its west bank, near the modern town of Kalar, has been suggested as the site of Simurrum.[29] The upper mound has an area of 5.5 hectares. While the site is completely built over now, early satellite photographs indicate that there was a 100 hectare lower town. Second millennium BC pottery is often found during construction.[30]

A complication is that when a city-state captured large numbers of soldiers etc. they were sometimes placed in rural settlements named after their origin, a practice that continued into Neo-Babylonian times. There were settlements near Girsu/Lagash named Lullubu(na) and Šimurrum for example.[31]

A number of text closely link Karaḫar and Simurrum and they are though to be in the same area. Karaḫar is thought to be between Simurrum and Eshnunna.[32] One of Sulgi's late year names was "Year Karaḫar was defeated for the second time".[33] Two ensis of Karaḫar under the Ur III empire are known, Ea-rabi and Arad-Nanna.[34]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) King Iddin-Sin of the Kingdom of Simurrum, holding an axe and a bow, trampling a foe (c. 2000 BCE). Israel Museum.

King Iddin-Sin of the Kingdom of Simurrum, holding an axe and a bow, trampling a foe (c. 2000 BCE). Israel Museum. Stela of Iddi-Sin, King of Simurrum. It dates back to the Old-Babylonian Period. From Qarachatan Village, Sulaymaniyah Governorate, Iraqi Kurdistan. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq

Stela of Iddi-Sin, King of Simurrum. It dates back to the Old-Babylonian Period. From Qarachatan Village, Sulaymaniyah Governorate, Iraqi Kurdistan. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq

.jpg.webp) Outline of relief I (extracted). Beardless warrior with axe, trampling a foe. Sundisk above. A name "Zaba(zuna), son of ..." can be read.[35]

Outline of relief I (extracted). Beardless warrior with axe, trampling a foe. Sundisk above. A name "Zaba(zuna), son of ..." can be read.[35]

See also

- Anobanini rock relief – Rock relief from the Isin-Larsa period

References

- Shaffer, Aaron (2003). "Iddi(n)-Sîn, King of Simurrum: A New Rock-Relief Inscription and a Reverential Seal". Zeitschrift für Assyrologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie. Zeitschrift für Assyoriologie. 93 (1): 7–12.

- Eidem, Jesper (2001). The Shemshāra Archives 1: The Letters. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. p. 24. ISBN 9788778762450.

- Frayne, D.R., "On the location of Simurrum" in Crossing Boundaries and Linking Horizons: Studies in Honor of Michael C. Astour, pp. 243-269, 1997

- George, A., "The Sanctuary of Adad at Zabban? A Fragment of a Temple List in Three Sub-columns", BiOr. 65, pp. 714–717, 2008

- Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. Routledge. pp. 115–116. ISBN 9781134520626.

- Hallo W.W., Simurrum and the Hurrian Frontier, Revue Hittite et Asianique, pp. 71-81, 1978

- Frayne, Douglas (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BCE). University of Toronto Press. pp. 707–716. ISBN 9780802058737.

- Shaffer, Aaron (2003). "Iddi(n)-Sîn, King of Simurrum: A New Rock-Relief Inscription and a Reverential Seal". Zeitschrift für Assyrologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie. Zeitschrift für Assyoriologie. 93 (1): 32–35.

- Seidl, U., Das Relief, in A. Shaffer and N. Wasserman, Iddi(n)-Sin, King of Simurrum: A New Rock Relief Inscription and a Reverential Seal, ZA 93, 39-52, 2003

- J. G. Westenholz, "Legends of the Kings of Akkade", Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1997

- Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. p. 120. ISBN 9781438453255.

- Fouadi, A. H. A., Inscriptions and Reliefs from Bitwata.", Sumer, vol. 34, no. 1-2, pp. 122–29, 1978

- "T2K1.htm". cdli-gh.github.io.

- Potts, D. T. (2016). The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State. Cambridge University Press. p. 92-93. ISBN 978-1-107-09469-7.

- "Year Names of Sargon". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- Álvarez-Mon, Javier; Basello, Gian Pietro; Wicks, Yasmina (2018). The Elamite World. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-317-32983-1.

- "T2K3.htm". cdli-gh.github.io.

- Cohen, Mark E., "A New Naram-Sin Date Formula.", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 227–32, 1986

- Finkelstein, J. J., "Subartu and Subarians in Old Babylonian Sources", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–7, 1955

- Owen, David I., and S. Graziani, "The royal gift seal of Ṣilluš-Dagan, Governor of Simurrum." Studi sul Vicino Oriente antico dedicati alla memoria di Luigi Cagni 61, pp.815-846, 2000

- Collon, Dominique, "The Life and Times of TEḪEŠ-ATAL", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 84, no. 2, pp. 129–36, 1990

- Meijer, Diederik J. W., "Marginal and Steppic Areas as Sources for Archaeological Debate: A Case for “Active Symbiosis” of Town and Country", Constituent, Confederate, and Conquered Space: The Emergence of the Mittani State, edited by Eva Cancik-Kirschbaum, Nicole Brisch and Jesper Eidem, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 163-178, 2014

- Frayne, Douglas, "Šū-Sîn E3/2.1.4", in Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 285-360, 1997

- Jacobsen, Thorkild., "The Reign of Ibbī-Suen.". Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 1953

- Sasson, Jack M., "Scruples: Extradition in the Mari Archives", Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Des Morgenlandes, vol. 97, pp. 453–73, 2007

- Albright, W. F., "Notes on the Topography of Ancient Mesopotamia", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 46, pp. 220–30, 1926

- Ismail, Bahijah Kh., and J. Nicholas Postgate, "A Middle Assyrian Flock-Master’s Archive from Tell Ali", Iraq, vol. 70, pp. 147–78, 2008

- Ismail, Bahijah Kh., "Informationen iiber Tontafeln aus Tell-Ali", in H. Klengel (ed.), Gesellschaft und Kultu im alten Vorderasien, Schriften zur Geschichte und Kultur des alten Orients 15, Berlin, 1982

- Casana, Jesse, and Claudia Glatz, "The land behind the land behind Baghdad: archaeological landscapes of the upper Diyala (Sirwan) river valley", Iraq, vol. 79, pp. 47–69, 2017

- Glatz, Claudia, and Jesse Casana, "Of highland-lowland borderlands: Local societies and foreign power in the Zagros-Mesopotamian interface", Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 44, pp. 127-147, 2016

- Steinkeller, Piotr, "Corvée labor in Ur III times", From the 21st Century BC to the 21st Century AD 10 (2013), pp. 327-424, 2018

- Ghobadizadeh, Hamzeh and Sallaberger, Walther, "Šulgi in the Kuhdasht Plain: Bricks from a Battle Monument at the Crossroads of Western Pish-e Kuh and the Localisation of Kimaš and Ḫurti", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 113, no. 1, pp. 3-33, 2023

- Al-Mutawalli, Nawala, Sallaberger, Walther and Shalkham, Ali Ubeid, "The Cuneiform Documents from the Iraqi Excavation at Drehem", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 151-217, 2017

- Owen, David I., "Transliterations, Translations, and Brief Comments", The Nesbit Tablets, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 13-110, 2016

- Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781438453255.

- Osborne, James F. (2014). Approaching Monumentality in Archaeology. SUNY Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 9781438453255.

External links

Media related to Simurrum at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Simurrum at Wikimedia Commons- Ancient History.The Secret History of Iddi-Sin’s Stela