Iraqi art

Iraqi art is one of the richest art heritages in world and refers to all works of visual art originating from the geographical region of what is present day Iraq since ancient Mesopotamian periods. For centuries, the capital, Baghdad was the Medieval centre of the literary and artistic Arab world during the Abbasid Caliphate, in which Baghdad was the capital, but its artistic traditions suffered at the hands of the Mongol invaders in the 13th century. During other periods it has flourished, such as during the reign of Pir Budaq, or under Ottoman rule in the 16th century when Baghdad was known for its Ottoman miniature painting.[1] In the 20th century, an art revival, which combined both tradition and modern techniques, produced many notable poets, painters and sculptors who contributed to the inventory of public artworks, especially in Baghdad. These artists are highly regarded in the Middle East, and some have earned international recognition. The Iraqi modern art movement had a profound influence on pan-Arab art generally.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iraq |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

History

Mesopotamian art

Iraq's art has a deep heritage that extends back in time to ancient Mesopotamian art. Iraq has one of the longest written traditions in the world. Maqam traditions in music and calligraphy have survived into the modern day.[3] However, the continuity of Iraq's arts culture has been subject to the vicissitudes of invading armies for centuries. The Mongol invasion of the 13th century devastated much traditional art and craft and is generally seen as a break in the tradition of Iraqi art.[4]

Although British archaeologists excavated a number of Iraqi sites, including Nimrud, Nineveh and Tell Halaf in Iraq in the 19th century,[5] they sent many of the artefacts and statues to museums around the world. It was not until the early 20th century, when a small group of Iraqi artists were awarded scholarships to study abroad, that they became aware of ancient Sumerian art by visiting prestigious museums such as the Louvre, enabling them to reconnect with their cultural and intellectual heritage.[6] Nevertheless, figurines, dating to the Neolithic period, found at the Palace of Tell Halaf and elsewhere, attest to Iraq's ancient artistic heritage.

The Sassanids ruled the region that is now Iraq and Iran between the 3rd and 7th centuries. Sasanian art is best represented in metalwork, jewellery, architecture and wall-reliefs. Few paintings from this period have survived, but an understanding of jewellery ornamentation can be inferred from pictorial and sculptural representations.[7] The art historian, Nada Shabout, points out that Iraqi art remains largely undocumented. The West has very little idea about Iraqi art. Problems associated with documenting a complete picture of Iraqi art have been compounded by the fact that many 20th-century artists, art historians and philosophers have been forced into exile, where they are isolated from their heritage and current practices.[8] In addition, much of Iraq's art heritage has been looted or destroyed during periods of revolution, war and political unrest.[9]

During the early Islamic period, writing was transformed into an "iconophoric message...a carrier of meaning independent of its form [and] into a subject worthy of the most elaborate ornamentation."[10] Another development during this period was the use of repeating patterns or motifs on scrolls and wall-reliefs. Inherited from the Muslims, this highly stylised system of ornamentation was subsequently given the label of arabesque.[10]

Abbasid art

The Abbasid Dynasty developed in the Abbasid Caliphate between 750 and 945, primarily in its heartland of Mesopotamia. The Abbasids were influenced mainly by Mesopotamian architectural traditions and later influenced neighbouring styles such as Persian as well as Central Asian styles.

Between the 8th and 13th-centuries. During the Abbasid period, pottery achieved a high level of sophistication, calligraphy began to be used to decorate the surface of decorative objects and illuminated manuscripts, particularly Qur'anic texts became more complex and stylised.[11] Iraq's first art school was established during this period, allowing artisans and crafts to flourish.[12]

At the height of the Abbasid period, in the late 12th century, a stylistic movement of manuscript illustration and calligraphy emerged. Now known as the Baghdad School, this movement of Islamic art was characterised by representations of everyday life and the use of highly expressive faces rather than the stereotypical characters that had been used in the past. The school consisted of calligraphers, illustrators, transcribers and translators, who collaborated to produce illuminated manuscripts derived from non-Arabic sources. The works were primarily scientific, philosophical, social commentary or humorous entertainments. This movement continued for at least four decades, and dominated art in the first half of the 13th century.[13] Poetry also flourished during the Abbasid period, producing notable poets including: the 9th-century Sufi poets Mansur Al-Hallaj and Abū Nuwās al-Ḥasan ibn Hānī al-Ḥakamī.

The Abbasid artist, Yahya Al-Wasiti lived in Baghdad in the late Abbasid era (12th to 13th-centuries) was the pre-eminent artist of the Baghdad school. His most well-known works include the illustrations for the book of the Maqamat (Assemblies) in 1237, a series of anecdotes of social satire written by al-Hariri.[14] Al-Waiti's illustrations served as an inspiration for the 20th-century modern Baghdad art movement.[15] Other examples of works in the style of the Baghdad School include the illustrations in Rasa'il al-Ikhwan al-Safa (The Epistles of the Sincere Brethren), (1287); an Arabic translation of Pedanius Dioscorides’ medical text, De Materia Medica (1224)[13] and the illustrated Kalila wa Dimna (Fables of Bidpai), (1222); a collection of fables by the Hindu, Bidpai translated into Arabic.[16]

For centuries, Baghdad was the capital of the Abbasid caliphate; its library was unrivalled and a magnet for intellectuals around the known world. However, in 1258, Baghdad fell to the Mongol invaders, who pillaged the city, decimating mosques, libraries and palaces, thereby destroying most of the city's literary, religious and artistic assets. The Mongols also killed between 200,000 and one million people, leaving the population totally demoralised and the city barely habitable.[17] Iraqi art historians view this period as a time when the "chain of pictorial art" was broken.[6]

Between the years 1400-1411 Iraq was ruled by the Jalayirid dynasty. During this time, Iraqi art and culture flourished. Between 1411 and 1469, during the rule of the Qara Quyunlu dynasty artists from different parts of the eastern Islamic world were invited to Iraq. Under the patronage of Pir Budaq, son of the Qara Quyunlu ruler, Jahan Shah (r. 1439–67), Iranian styles from Tabriz and Shiraz and even the styles of Timurid Central Asia were all brought together in Iraq. Baghdad's importance as a centre of the arts declined after Pir Budaq's death in 1466. The Qara Quyunlu period ended with the advent of the Aq Quyunlu. Though noted patrons of the arts, the Aq Quyunlu mostly focus on areas outside Iraq.[18]

Between 1508 and 1534, Iraq came under the rule of the Safavid dynasty, which shifted the focus of arts to Iran. Baghdad experienced a revival in the arts during this period, and was also a centre for literary works. The poet Fuzûlî (ca. 1495–1556) wrote during the period. He wrote in the three dominant languages of his time: Arabic, Persian, and Turkish. Iraq was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1534, during the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent. The Iraqi poet Fuzûlî wrote in Arabic, Persian and Turkish during this time, and continued writing poetry after Ottoman rule was established in 1534.[18] During the 16th century, Baghdad underwent another period of artistic revival; Iraqi painting from this time is called the “Baghdad school” of Ottoman miniature painting.[18]

Iraqi experienced a cultural shift between the years 1400 and 1600 CE, which is also reflected in its arts. In the 16th century, political rule in Iraq transitioned from the Turco-Mongol dynasties to the Ottoman Empire. In its past Iraq had been a centre of illuminated manuscripts but this art form experienced a general decline during this period.[18]

Statuary, wall paintings and jewellery from ancient sites in Iraq

The Assyrian relief of Ashur as a feather. This is one of the best-known symbols used by the people of ancient Mesopotamia.

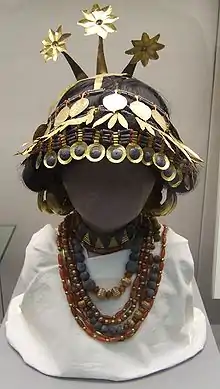

The Assyrian relief of Ashur as a feather. This is one of the best-known symbols used by the people of ancient Mesopotamia. Sumerian Headgear and Necklaces British Museum. This artifact was found in the tomb of Puabi in the "Royal tombs" of Ur.

Sumerian Headgear and Necklaces British Museum. This artifact was found in the tomb of Puabi in the "Royal tombs" of Ur..jpg.webp) Shalmaneser III, on the Throne Dais of Shalmaneser III at the Iraq Museum.

Shalmaneser III, on the Throne Dais of Shalmaneser III at the Iraq Museum.

Stele with carved relief from Nimrud

Stele with carved relief from Nimrud.png.webp) Sumerian account of silver for the governor from Shuruppak, c. 2,500 BCE

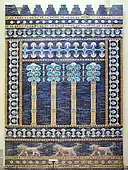

Sumerian account of silver for the governor from Shuruppak, c. 2,500 BCE Facade of the Throne Room. Babylon

Facade of the Throne Room. Babylon Wall relief from Ninevah featuring an Assyrian soldier, about to behead a prisoner from the city of Lachish. 700-692 BCE. Currently housed in the British Museum

Wall relief from Ninevah featuring an Assyrian soldier, about to behead a prisoner from the city of Lachish. 700-692 BCE. Currently housed in the British Museum The Royal Lion Hunt, Nineveh (north palace), 645-635BCE

The Royal Lion Hunt, Nineveh (north palace), 645-635BCE Lion of Babylon, date uncertain, possibly of Hittite origin

Lion of Babylon, date uncertain, possibly of Hittite origin The Ishtar Gate

The Ishtar Gate The Assyrian Gallery at Iraq Museum

The Assyrian Gallery at Iraq Museum.jpg.webp)

Standard of Ur - Peace Panel - Sumer

Standard of Ur - Peace Panel - Sumer

Selected artwork and handcrafts from post-Islamic structures and sites in Iraq

Incantation bowl, Mesopotamia, Sassanid period, 6th or 7th century

Incantation bowl, Mesopotamia, Sassanid period, 6th or 7th century Plaster with boar relief, Ctesiphon, Iraq, Sassanid period, 6th or 7th century

Plaster with boar relief, Ctesiphon, Iraq, Sassanid period, 6th or 7th century Silver bracelet, Iraq, 9th or 10th century

Silver bracelet, Iraq, 9th or 10th century Calligraphic plate, Iraq, Abbasid period, 10th century AD

Calligraphic plate, Iraq, Abbasid period, 10th century AD

.jpg.webp) Text and illustration from an Arabic translation of De Materia Medica in the style of the Baghdad School, 13th century

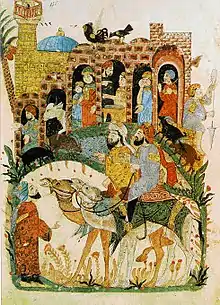

Text and illustration from an Arabic translation of De Materia Medica in the style of the Baghdad School, 13th century Illustration from Maqamat in the style of the Baghdad School, 13th century

Illustration from Maqamat in the style of the Baghdad School, 13th century._Baghdad._Views%252C_street_scenes%252C_and_types._A_Sabean_silversmith._At_work_in_his_jewelry_store._A_Sabean-sect_who_venerate_John_the_Baptist_LOC_matpc.15983.jpg.webp) A Mandaean silversmith at work in his Baghdad store, 1932

A Mandaean silversmith at work in his Baghdad store, 1932

Arabesque decoration, Karbala

Arabesque decoration, Karbala Great Mosque of Samarra

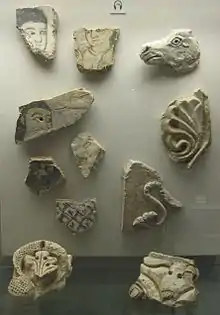

Great Mosque of Samarra Fragments of stucco from Samarra, including paintings, carvings and abstract patterns

Fragments of stucco from Samarra, including paintings, carvings and abstract patterns Carved stucco panel from the city of Samarra. Floral pattern with Abbasid geometric designs, grapes, vines, and ears of pine cones. third Islamic century AH (9th century)

Carved stucco panel from the city of Samarra. Floral pattern with Abbasid geometric designs, grapes, vines, and ears of pine cones. third Islamic century AH (9th century)

19th century

_(14741970056).jpg.webp)

Until the 20th century, Iraq had no tradition of easel painting. Traditional art, which included metal-work, rug-making and weaving, glass-blowing, ceramic tiles, calligraphy and wall murals were widely practised during the 19th century. Some traditional practices traced their origins back to the 9th-century Assyrians. However, in the 19th century, mural painters were generally seen as artisans rather than artists - although in traditional Islamic society, the distinction between artists and artists was not well defined.

A few named individuals are known, including the painter, Abbud 'the Jewish' Naqqash and the calligrapher, painter and decorator; Hashem Muhammad al-Baghdadi ("Hashim the Calligrapher", early 20th century) (died 1973) and Niazi Mawlawi Baghdadi (19th century), but relatively few details of their lives and careers are known.[19]

In the late 19th century, the rise of nationalistic and intellectual movements across the Arab world led to calls for an Arab-Islamic cultural revival. Artists and intellectuals felt that the growth in Western influences was a threat to Arab cultural identity.

At the same time as local artists began to adopt Western practices such as easel painting.[20] they also searched consciously for a distinct national style.[21]

20th century

The late 19th century and early 20th century are known as Nahda in Arabic. This term loosely translates as a "revival" or "renaissance." Nahda became an important cultural movement which influenced all art forms - architecture, literature, poetry and the visual arts.[22]

At the turn of the 20th century, a small group of Iraqis were sent to Istanbul for military training, where painting and drawing was included as part of the curriculum.[23] This group, which became known as the Ottoman artists, included Abdul Qadir Al Rassam (1882–1952); Mohammed Salim Moussali (1886-?); Hassan Sami, Asim Hafidh (1886–1978); Mohammed Saleh Zaki (1888–1974) and Hajji Mohammed Salim (1883–1941).[24] were exposed to European painting techniques.[25]

Their style of painting was realism, impressionism or romanticism.[26] On their return to Baghdad, they set up studios and began to offer painting lessons to talented, local artists.

Many of the next generation of artists began by studying with the artists from the Ottoman group.[27] Their public works, which included murals, public monuments and artworks in the foyers of institutions or commercial buildings, exposed Iraqi people to Western art and contributed to art appreciation.[25]

As Middle-Eastern nations began to emerge from colonial rule, a nationalist sentiment developed. Artists consciously sought out ways to combine Western art techniques with traditional art and local subject matter. In Iraq, 20th century artists were at the forefront of developing a national style, and provided a model for other Arab nations who wanted to forge their own national identities.[28]

Literature

Poetry and verse remains a major art form in modern Iraq and Iraqi poets were inspired by the literature of the 15th and 16th-centuries when Iraq was the centre of Arabic world. Notable 20th-century poets include Nazik Al-Malaika (1923–2007), one of the best known woman poets in the Arab world and who wrote the poem My Brother Jafaar for her brother, who was killed during the Al-Wathbah uprising in 1948; Muḥammad Mahdī al-Jawāhirī (1899–1997); Badr Shakir al-Sayyab (1926–1964); Abd al-Wahhab Al-Bayati (1926–1999)[29] Ma'rif al-Rasafi (1875–1845); Abdulraziq Abdulwahed (b. 1930); the revolutionary poet, Muzaffar Al-Nawab (b. 1934); Buland Al Haidari (b. 1926) and Janil Sidiq al-Zahaiwi (1863–1936). In post-war Iraq, poetry was very much influenced by the political and social upheavals that Iraqis had experienced throughout the 20th century and with many poets living in exile, themes of 'strangeness' and 'being a stranger' often dominated contemporary poetry.[30]

Iraqi poets, including Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, often turned to Iraqi folklore which they often integrated with Western mythology.[31] He is considered one of the most influential Arab poets because he was the first to develop the free form style of poetry, and therefore a prime mover in the development of modernist poetry.[32] Contemporary Iraqi poetry is considerably freer than traditional verse, and is imbued with social and political awareness.[33]

Photography

Scholars point out that very little is known about photography in Iraq.[34] Iraq was relatively slow to adopt photography as an industry and art form, due to the religious and social prohibitions on making figurative images. The first camera entered Iraq as late as 1895 when an Iraqi photographer, Abdul-Karim Tabouni, from Basra, returned to Iraq following a trip to India where he had studied the art of photography. He founded a photographic studio and practiced this profession for many years.[35]

In the 19th century, demand for photography came from three main sources: archaeological expeditions who needed to document sites as well as artefacts that were too cumbersome or too fragile to transport; religious missions who documented religious sites and tourists travelling through the Middle East as part of a grand tour. In the first decades of the 20th century, the military also became an important source of business as officers sought photographs and photographic equipment. [36]

In the first decades of the 20th century, several factors contributed to the spread of photography. Firstly, British and European archaeologists began using photography to document ancient sites in the second half of the 19th century. Religious missionaries were also using the camera to document historic religious sites. These activities exposed local Iraqis to the technology, and provided young men with employment opportunities as photographers and camera-men assisting archaeological teams. For instance, throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, the American anthropologist, Professor Henry Field was involved in several expeditions to ancient Mesopotamian sites and in his publications, he acknowledged the assistance of Iraqi photographer by the name of Shauqat (who was a nephew of the photographer, Abdul-Karim Tiouti). The writer, Gertrude Bell also reports training a young boy in the process of developing photographs in Baghdad in 1925.[37] A second factor was that, in the 1920s, King Faisal I arranged for a photographic portrait of his wife, thereby popularising photographic portraiture.[38]

In the years following the First World War, a number of photographers arrived in Iraq. Some of these were displaced Armenians, who had prior experience working with precision equipment, including cameras.[39] These early photographers were mostly concerned with photographing military scenes and personnel. Around this time, a photographer named Tartaran, set up a studio at the entrance to the Mosul Elementary School.[40] From there, local school children could observe the photographer at work. The influential Mosul photographer, Murad al-Daghistani, who specialised in capturing the life and work of every-day people in Mosul, may have developed his passion for photography after watching Tartaran developing photographs in his dark-room. By the 1940s, the number of photographic studios had proliferated, especially in Mosul, Basra and Baghdad. Important 20th-century Iraqi photographers include: Amri Salim, Hazem Bak, Murad Daghistani, Covadis Makarian, Sami Nasrawi, Ahmed Al-Qabbani, Jassem Al-Zubaidi, Fouad Shaker and Rashad Ghazi amongst others.[38]

The earliest photographers used the medium to record an Iraqi way of life that was in danger of being lost as the country 'modernised'. The photographer, Latif al-Ani, who is often described as the "father of Iraqi photography", was very much concerned with documenting cosmopolitan Iraqi life in the 1950s, as he saw it.[41] By the mid-20th century, photography had become a popular medium for expressing social and political concerns. The artist, Jananne al-Ani has explored the dichotomy of Orient/ Occident in her work, and has also used photography to question the wearing of the veil while Halim Alkarim uses blurred images to suggest the political instability of Iraq.[42]

Architecture

Modern architecture presented contemporary architects with a major challenge. A continuous tradition of both domestic and public architecture was evident, but failed to conform with modern materials and methods.[33] From the early 20th century, architecture employed new styles and new materials and public taste became progressively modern. The period was characterised by original designs produced by local architects, who had been trained in Europe, including: Mohamed Makiya, Makkiyya al-Jadiri, Mazlum, Qatan Adani and Rifat Chadirji.[43]

Like visual artists, Iraqi architects searched for a distinctly national style of architecture and this became a priority in the 20th century. Mohammed Makkiyya and Rifat Chadirji were the two most influential architects in terms of defining modern Iraqi architecture.[44] The architect, Chadirji, who wrote a seminal book on Iraqi architecture, called this approach international regionalism.[45] He explains:

"From the very outset of my practice, I thought it imperative that, sooner or later, Iraq create for itself an architecture regional in character yet simultaneously modern, part of the current international avant-garde style."[46]

Architects sought an architectural language that would remind visitors of ancient Iraqi architectural history.[47] To that end, architects used Iraqi motifs in their designs[48] and incorporated traditional design practices, such as temperature control, natural ventilation, courtyards, screen walls and reflected light within their work.[47] Architects also became designers who designed furniture and lighting with reference to the peculiarities of Iraqi climate, culture and material availability.[33]

As cities underwent a period of "modernisation" in the early decades of the 20th century, traditional structures came under threat and subject to demolition.[49] The mudhif (or reed dwelling) or the bayt (houses) with features such as the shanashol (the distinctive oriel window with timber lattice-work) and bad girs (wind-catchers) were being lost with alarming haste.[50]

The architect, Rifat Chadirji along with his father, Kamil Chadirji, feared the vernacular architecture and ancient monuments would be lost to the new development associated with the oil boom in the mid-century.[51] They documented the region photographically and in 1995, published a book entitled, The Photographs of Kamil Chadirji: Social Life in the Middle East, 1920-1940, which recorded the buildings and lifestyles of the Iraqi people.[52]

The artist, Lorna Selim, who taught drawing at Baghdad University's Department of Architecture, in the 1960s took her students to sketch traditional buildings along the Tigris and was especially interested in exposing young architects to Iraq's vernacular architecture, alley-ways and historical monuments. The work of Selim and Chadirji inspired a new generation of architects to consider including traditional design features - such as Iraqi practices of temperature control, natural ventilation, courtyards, screen walls and reflected light - in their designs.[53]

Visual arts

During the first three decades of the 20th century, there was little progress in art. Following World War One, a group of Polish officers, who had been part of the Foreign Legion,[54] arrived in Baghdad and introduced local artists to a European style of painting, which in turn fostered a public appreciation of art. The Institute of Fine Arts and the Fine Arts Society were established in 1940-41[55] and the Iraqi Artists' Society was founded in 1956, after which many exhibitions were mounted.[56]

In 1958, British rule was overthrown and Abdul Karim Qasim assumed power. This led to triumphant demonstrations and expressions of national pride. In early 1959, Qasim commissioned Jawad Saleem to create Nasb al-Hurriyah (Monument to Freedom,) to commemorate Iraq's independence.[57] Artists began to look to their history for inspiration and employed arabesque geometry and calligraphy as visual elements in their compositions, and referred to folk tales and scenes drawn from everyday life for artistic inspiration.[58]

In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, the Ba'ath Party mounted a program to beautify the city of Baghdad which led to numerous public art works being commissioned. Designed to instil a sense of national pride within the population, and to immortalise the leader, Saddam Hussein, these works provided work opportunities to the nation's architects, engineers and sculptors.[59] During this period, artists showed a distinct preference for abstract works, which allowed them to evade censorship.[60] Baghdad is now dotted with monuments, including Al-Shaheed Monument and The Monument to the Unknown Soldier and the Victory Arch, along with many smaller statues, fountains and sculptures; all constructed in the second half of the 20th century, and showing increasing levels of abstraction over time.[61]

A notable feature of the Iraqi visual arts scene lies in artists' desires to link tradition and modernity in artworks. For a number of artists, the use of calligraphy or script has become an important part of integrating traditional artistic elements into an abstract artwork. In this way, the use of letters connects Iraqi artists with the broader hurufiyya movement (also known as the North African Lettrist Movement). The Iraqi artist, Madiha Omar, who was active from the mid-1940s, was one of the pioneers of the hurufiyya movement, since she was the first to explore the use of Arabic script in a contemporary art context and exhibited hurufiyya-inspired works in Washington as early as 1949.[62]

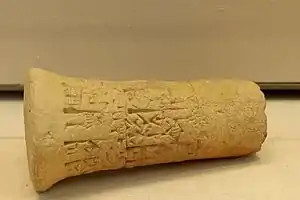

Clay cylinder from Girsu, c. 2400 BCE

Clay cylinder from Girsu, c. 2400 BCE

Art groups

Artists’ desire to tap into Iraq’s art heritage within the context of contemporary artworks stimulated the formation of art groups, many of which codified their aims and objectives in manifestos that were published, often in the local press. [63] These developments contributed to a unique aesthetic in the contemporary Iraqi art movement. Art historians have commented: [64]

Accordingly, the 20th-century Iraqi arts scene is notable for the number of different art groups or art movements that emerged in the post-colonial period. Each of these groups sought to forge a national art aesthetic that acknowledged Iraq's deep art heritage and incorporated it in contemporary artworks. Although there were tensions in the different visions of these groups,[65] collectively, they actively searched for new national vision which would enable the country to develop internally, as well as take its place on a world stage.[66] These groups include:

The Pioneers (Al-Ruwad)

- The Pioneers, Iraq's first modern art group, was formed by painter, Faiq Hassan in the 1930s. This group was stimulated by the contact between Iraqi artists and European artists who had resided in Iraq during the war.[67] This group consciously developed a distinct Iraqi style by incorporating local phenomena and traditional village life into artworks.[68] They rejected the artificial atmosphere of the artist’s studio and encouraged artists to engage with nature and traditional Iraqi life. They held their first exhibition in 1931.[69]

- This group was responsible for taking the first steps towards bridging the gap between modernity and heritage. Artists active in the group had been educated abroad, returned with a European aesthetic, yet wanted to paint local scenes and landscapes. Members included: Faeq Hassan, Jawad Saleem, Ismail al Sheikhli, Nadhim Ramzi and the architect-painter, Kamil Chadirji.[70] The group continued to meet into the 1970s, although some of its high profile members withdrew from the group at different times. For instance, Faeq Hassan left the group in 1962.[71] Jawad Saleem and Shakir Hassan Al Said also broke away from the Pioneers and formed a different group in 1951.[72]

The Avantgarde Group and later known as the Primitive Group (Jum'at al Ruwwad)

- Formed in 1950, the Jum'at al Ruwwad (Avantgarde Group) was inspired by Mespotamian art and Iraqi folklore. It later changed its name to the Primitive Group.[73] The group was initially led by Faeq Hassan (Baghdad 1914-1992) and later by Isma'il al-Shaykhali (Turkey b. 1927). Artists in this group were inspired by ancient art of the 13th-century Baghdad School.[15] Members of this group included: Ismail Al-Sheikhly, Issa Hanna Dabish, Zeid Salih, Mahmoud Sabri, Khalid Al Qassab, Dr Qutaiba Al Sheikh Nouri, Dr Nouri Mutafa Bahjat, Kadhem Hayder, Nuri al-Rawi, Ghazi Al Saudi, Mahmoud Ahmed, Mohammed Ali Shakir, Sami Haqqi, Hassan Abid Alwan, Jawad Saleem and Lorna Saleem.[74]

The Baghdad Modern Art Group (Jama’et Baghdad lil Fen al-Hadith)

- Established in 1951, by Jawad Saleem and Shakir Hassan Al Said, after they broke away from the Pioneers group,[72] its aims were to reassert a national identity and use art to build a distinctive Iraqi identity which referenced its ancient heritage and tradition.[77] Hassan, the group's leader promoted the idea of istilham al-turath – "seeking inspiration from tradition" and wrote a manifesto.[78] The co-founder, Hassan, wrote that, after the 1958 independence, artists were no longer responsible for preserving art and culture, instead the state was responsible for "turath" - safeguarding public taste; all that remained was for artists to absorb turath, free from historical responsibility.[79] Hassan, and others, believed that earlier artists, such as Jawad Saleem, had shouldered too great a burden of historical responsibility.[80] This group is credited with being the first Islamic art group to develop a local style.[19]

_(14580924750).jpg.webp) The original bust of the Sumerian Queen, Shuba'ad, displayed at the Iraq Museum, for which al-Kahal made a replica

The original bust of the Sumerian Queen, Shuba'ad, displayed at the Iraq Museum, for which al-Kahal made a replica

- While the Modern Art Group sought to connect with Islamic tradition, the group was distinguished from earlier art groups in that it sought to express modern life, while keeping tradition and heritage in perspective.[81] Key members of this group included: Nuri al-Rawi (b. 1925) who became the Minister for Culture; Jabra Ibrahim Jabra (1920-1994); Mohammed Ghani Hikmat (1929-2011); Khaled al-Rahal (1926-1987) and 'Atta Sabri (1913-1987), all of whom had been members from the group's foundation,[82] as well as Mahmud Sabri (1927-2012); Tariq Mazlum (b.1933), Nuri al-Rawi (b. 1925), Mahmoud Sabri (b. 1927), Ata Sabri (b.1913), and Kadhim Hayder.[83] The Baghdad Modern Art Group was moribund within a decade of its formation.[84] One of its co-founders, Jawad Saleem died in 1961, while the other co-founder, Shakir Hassan Al Said, suffered a mental and spiritual crisis as a result of the continuing turbulence and political instability following the 1958 revolution and the overthrow of the Hashemite monarchy.[85]

The Impressionists

- The Impressionists emerged in 1953, and organised around the artist, Hafidh al-Droubi (1914-1991), who had trained in London and had turned to impressionism and cubism.[86] In the second half of the 20th century, a trend towards abstraction was evident amongst Iraqi artists, who wanted to embrace a more modern aesthetic.[87] However, al-Droubi pointed out that the Iraqi landscape, with its endless horizons, bright colours and open fields, was quite different to European landscapes and required different techniques. Unlike the art groups that preceded it, the Impressionists published no manifesto, and lacked the philosophical underpinnings evident in the Baghdad Modern Art Group or the New Vision.[88]

The Innovationists (Al Mujadidin)

- Established in 1965, the Al Mujadidin was formed by a group of younger artists including: Salim al-Dabbagh, Faik Husein, Saleh al-Jumai'e and Ali Talib.[89] Group members were united along intellectual, rather than stylistic grounds. This group, which lasted only four years,[71] rebelled against traditional art styles and explored the use of new materials such as collage, aluminum and mono-type.[90] These artists exhibited distinct individual styles, but often chose war and conflict for their themes, especially the 1967 war.[91]

The Corners Group (Majmueat Al-Zawiya)

- Simply known as the al-Zawiya group, it was founded in 1967 by Faeq Hassan, against a highly political backdrop. This group wanted to use art to focus on social and political issues and to serve national causes. The group held just one exhibition in its inaugural year.[92]

The New Vision (Al-Ru’yah al-Jadida)

- Following decades of war and conflict, culminating in the July Revolution of 1958, artists began to feel free to find inspiration in a variety of sources.[93] The demise of the Baghdad Modern Art Group contributed to an environment where many artists worked individually, developing their own style, while still maintaining the broad trends of the Modern Baghdad Art group. Founded in 1968, by artists Ismail Fatah Al Turk; Muhammed Muhr al-Din, Hashimi al-Samarchi, Salih Jumai'e, Rafa al-Nasiri and Dia Azzawi,[94] Al-Ru’yah al-Jadida, represented a free art style where many artists believed that they needed to be true to their own era.[84] This group promoted the idea of freedom of creativity within a framework of heritage.[69]

- The group's manifesto articulated the need for new and daring ideas,[94] and read in part:

"We believe that heritage is not a prison, a static phenomenon or a force capable of repressing creativity so long as we have the freedom to accept or challenge its norms... We are the new generation. We demand change, progression and creativity. Art stands in opposition to stasis. Art is continually creative. It is a mirror to the present moment and it’s the soul of the future."[95]

One Dimension Group

- Founded in around 1971 by the Iraqi artist and intellectual, Shakir Hassan Al Said, this group sought a new artistic identity, drawn from within Iraqi culture and heritage. The group's founder, Al Said, published a manifesto for the group in the Iraqi newspaper, al-Jamhuriyyah, in which he outlined his vision for a national art aesthetic.[96] The objectives of the One Dimension Group were multi-dimensional and complex. For al-Said, the one dimension was "eternity' - the relationship between the past and the present - the linking of Iraq's artistic heritage with modern abstract art.[97] The group held their first exhibition in 1971.[98]

- In practice, this group blended Arabic motifs, especially calligraphy, albeit in a deconstructed form, and geometric shapes into their contemporary and abstract artworks.[99] The impact of this group was significant for the Calligraphic School of Art, which was based on the principles set out by Al-Said.[100] The New Vision had a lasting impact on the pan-Arab region, through the art movement known as hurufiyya.[101]

- Founding members of the One Dimension group include: Rafa al-Nasiri, Mohammed Ghani Hikmat, Nuri al-Rawi, Dia Azzawi, Jamil Hamoudi, Hashem Samarchi (b. 1939), Hashem al-Baghdadi (1917-1973) and Saad Shaker (1935-2005).[102]

Other 20th-century groups

Other art groups, including the Triangle Group, the Shadows (formed by Ali Talib) and the Academicians formed throughout the 1970s, but few lasted for more than a year or two.[100]

The Wall Group (Jamaat el-Jidaar)

- Established in 2007, this group of artists, many students at the Institute of Fine Arts, work on public projects in order to beautify the city of Baghdad. Paid a very modest stipend by the Ministry of Works, these artists have painted concrete slabs along the Tigris River, thereby transforming ruins left over from the revolution into modern works of art. The slabs had previously served as protection from bombardment. Although this group did little to develop a new aesthetic, it was able to provide employment and encouragement for young artists, who at that time were operating in a void since most of the artists of the preceding generation were living in exile.[103] Artists active in Jamaat el-Jidaar include Ali Saleem Badran and Gyan Shrosbree.[104]

Detail of Uruk Vase, 3200–3000 BCE

Detail of Uruk Vase, 3200–3000 BCE Untitled wall relief by Khaled al-Rahal, c. 1960 CE

Untitled wall relief by Khaled al-Rahal, c. 1960 CE

Notable Iraqi artists

Iraq has produced a number of world-class painters and sculptors including Ismail Fatah Al Turk (1934–2008), Khalid Al-Jadir (1924–1990), and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat.[29]

Faeq Hassan (1914–1992), considered the founder of modern plastic art in Iraq, was among several Iraqi artists who were selected to study art at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts before the Second World War. Hassan and the art group he founded formed the foundation of Iraq's strong 20th-century artistic tradition. Hassan founded the Institute of Fine Arts in Baghdad; many of Iraq's best known artists studied at this institution.[105]

Jawad Saleem (b. 1919) is a painter and sculptor from Baghdad who (together with Mohammed Ghani (1929–2011) and Hassan Shakir) (1925–2004), founded the influential Baghdad Modern Art Group in 1951. Saleem was commissioned to create the Monument of Freedom in Baghdad's city centre overlooking Liberation Square.[106] Saleem, and his student, Khaled al-Rahal have been described as "the two pillars of modern Iraqi art."[107]

Dia Azzawi's (b. 1939) work, described as contemporary art, includes references to Arabic calligraphy, as well as Sumerian and Assyrian art.[106] Azzawi has been the inspiration for many contemporary calligraffiti artists.

Jamil Hamoudi (1924–2003) is both a painter and sculptor. Like Azzawi, Hamoudi also studied at the Baghdad School of Fine Art. He was interested in the cubist movement and in 1947, he self-identified with the surrealist movement, only to later distance himself citing "A dark, saturnine atmosphere emanated from [their canvases] the effect of which was to arouse a feeling of despair in human beings." His paintings are brightly coloured and make use of shapes like circles, triangles and arches. For sculpture he frequently uses plaster, stone, wood, metal, copper, glass, marble, Plexiglas and ceramics.[106] In 1973 he was appointed to the directorship of the Fine Arts at the Ministry of Culture.

Other notable artists include: Madiha Omar (1908–2005) who is regarded as a pioneer of the Hurufiyya movement; Shakir Hassan Al Said (1925–2004); Hassan Massoudy (b. 1944); Khaled al-Rahal (1926–1987); Saadi Al Kaabi (b 1937); Ismael Al Khaid (b. abt 1900) and Rafa al-Nasiri (b. 1940).

Contemporary painting and sculpture by Iraqi artists

Al-Shaheed Monument Monument in Baghdad, sculpture designed by Ismail Fatah al-Turk, 1983

Al-Shaheed Monument Monument in Baghdad, sculpture designed by Ismail Fatah al-Turk, 1983.jpg.webp) Swords of Qādisīyah (also known as the Victory Arch) by Khaled al-Rahal and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat, 1989

Swords of Qādisīyah (also known as the Victory Arch) by Khaled al-Rahal and Mohammed Ghani Hikmat, 1989 Motherhood (also known as Mother and Child) statue by Khaled al-Rahal, 1961

Motherhood (also known as Mother and Child) statue by Khaled al-Rahal, 1961_-_Paris_in_France_-_Made_by_Hassan_Massoudy_in_2001.jpg.webp) Ecstasy (Al-Wajd) by Hassan Massoudy, 2001

Ecstasy (Al-Wajd) by Hassan Massoudy, 2001

Recent developments

From 1969, the Arab nationalist political agenda of the Ba'ath Party encouraged Iraqi artists to create work that would explain Iraq's new national identity in terms of its historical roots. The Iraqi Ministry of Culture is involved in efforts to preserve tradition Iraqi crafts like leather-working, copper-working, and carpet-making.[29]

In 2003, during the overthrow of the Ba'ath government, key institutions, including the Pioneers Museum and the Museum of Modern Art, were looted and vandalised. Approximately 8,500 paintings and sculptures, especially were stolen or vandalised. The occupying forces insisted on a voluntary return of stolen artworks, a position which resulted in very few works being returned. A few independent galleries purchased artworks with a view to returning them once a suitable national museum could be established.[108] A committee, headed by the respected artist and sculptor, Mohammed Ghani Hikmat, was formed with the objective of recovering stolen artworks and proved somewhat more effective.[109] By 2010, some 1,500 artworks had been recovered, including important works, such as the statue, Motherhood by Jawad Saleem.[110]

Since 2003, attempts at de-Ba'athification have been evident, with the announcement of plans to rid Baghdad's cityscape of monuments constructed during Saddam Husssein's rule. However, due to public pressure, plans have been made to store such monuments rather than arrange for their total destruction as had occurred in previous regimes. In addition, efforts are underway to erect new monuments which display significant figures from Iraq's history and culture. Recent developments also include plans to conserve and convert the former homes of Iraqi artists and intellectuals, including the artist Jawad Saleem, the poet Muhammad Mahdi al-Jawahiri, and others.[111]

In 2008, Iraq was again involved in violence as coalition forces entered the country. Many artists fled Iraq. The Ministry of Culture has estimated that more than 80 percent of all Iraqi artists are now living in exile.[112] The number of artists living abroad has created opportunities for new galleries in London and other major centres to mount exhibitions featuring the work of exiled artists from Iraqi and Middle Eastern. One such gallery is Soho's Pomegranate gallery established in the 1970s by the modernist Iraqi sculptor, Oded Halahmy, which not only mounts exhibitions, but also holds permanent collections of notable Iraqi artists.[113]

Shortages of art materials were commonplace in the aftermath of war.[114] However, visual artists such as Hanaa Malallah and Sadik Kwaish Alfraji turned to "found objects" and incorporated these into their artworks. Malallah consciously included shrapnel and bullets in her paintings and called this the Ruins Technique which allows her to not only make statements about war, but also to explore how objects become ruins.[115]

Literature, art and architecture are cultural assets in Iraq. However, certain archaeological sites, and museums have been ransacked by Islamic terrorists, notably the ancient city of Nimrud, near Mosul;[116] the Adad and Mashqi gates at Nineveh; the ancient city of Hatra[117] The United Nations has described acts of cultural vandalism as war crimes.[118] In 2014, Islamic militants invaded the city of Mosul, destroying ancient monuments and statues, which they perceived to be blasphemous, and ransacked the History Museum. Mostafa Taei, a resident of Hamam al-Alil was jailed by ISIL when the terrorists took over his town in 2014. ISIL banned any images or artworks of the human form, and Taei says he was beaten when the group learned that he was still painting. During this period, Taei's art "took a subversive turn, becoming a gruesome record of atrocities: decapitations, hangings, injured children and sobbing widows, all painted in an unschooled Naive art style." He also started to paint "martyr posters" that depict the soldiers and police officers who have died during the military operations to liberate Nineveh.[119]

The art historian, Nada Shabout, notes that the destruction of Iraqi art in the period after 2003, assumed both tangible and intangible forms. Not only were the artworks and art institutions looted or destroyed, but art production also suffered from the lack of availability of art materials and the loss of many intellectuals, including artists, who were forced into exile. This contributed to an environment that failed to nurture artists, and saw young, upcoming artists operating in a void.[120]

Iraqi monumental artworks, both ancient and modern, feature prominently on banknotes of the Iraqi dinar.

Selected bank-notes featuring monumental artwork

Art Museums and Galleries in Baghdad

The principal venues include:

- National Museum of Modern Art (formerly the Iraqi Museum of Modern Art) - established in 1962, it was badly damaged by vandals with many important artworks looted in 2003[121]

Mosul Museum is the second largest museum in Iraq after the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. It containins ancient Mesopotamian artifacts, mainly Assyrian.

Mosul Museum is the second largest museum in Iraq after the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. It containins ancient Mesopotamian artifacts, mainly Assyrian. - The Pioneers Museum, Baghdad - established in 1979 by the Ministry of Information and Culture, to house works by first generation native artists, it was also damaged with works looted in 2003[122]

- Hewar Art Gallery[123]Iraq Museum, BaghdadThe Baghdadi Museum

- Athar Art Gallery - opened in 1996 by Muhammed Znad[124]

- Dijla Art Gallery -opened in 1997 by Zainab Mahdi with the aim of encouraging young, upcoming artists[123]

- Madarat Gallery - opened in 2006 and hosts exhibitions, lectures, concerts and cultural sessions[125]

- Ruya Shop - opened in 2018 by Ruya Foundation on Mutanabbi Street and hosts exhibitions, film screenings, and a library.[126]

See also

- Art of Mesopotamia

- Arabic miniature

- Al-Hariri of Basra

- Baghdad College of Fine Arts

- Culture of Iraq

- Dur-Sharrukin

- Firdos Square statue destruction

- Fulgence Fresnel

- Hurufiyya movement

- List of Iraqi artists

- List of Iraqi women artists

- Julius Oppert

- Felix Thomas

Major Iraqi public monument/ statues and public buildings

- Al-Shaheed Monument. Baghdad

- Statue of Abu Ja'far al-Mansur, Baghdad

- List of mosques in Baghdad

- The Monument to the Unknown Soldier, Baghdad

- Victory Arch, Baghdad

- Timthal Baghdad (Baghdad's Statue) Baghdad

References

- Roxburgh, D.J., “Many a Wish Had Turned to Dust: Pir Budaq and the Formation of the Turkmen Arts of the Book,” Chapter 9 in: David J. Roxburgh (ed.)., Envisioning Islamic Art and Architecture: Essays in Honor of Renata Holod, Brill, 2014, pp 175-222

- Wijdan, A. (ed.), Contemporary Art From The Islamic World, p.166

- Rohde, A., State-Society Relations in Ba'thist Iraq: Facing Dictatorship, Routledge, 2010, Chapter 5

- Davis, B., "The Iraqi Century of Art," Artnet Magazine, July 2008, Online: http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/reviews/davis/davis7-14-08.asp

- Potts, D.T. (ed), A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Volume 1, John Wiley & Sons, 2012, p. 51-52; Pouillon, F., Dictionnaire des Orientalistes de Langue Française, KARTHALA, 2008, p. 924

- Shabout, N., "Jewad Selim: On Abstraction and Symbolism," in Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Arab World, Online

- Ettinghausen, E., Grabar, O. and Jenkins, M., Islamic Art and Architecture: 650-1250, Yale University Press, 2001, pp 66-68

- Shabout, N., "Ghosts of Futures Past: Iraqi Culture in a State of Suspension," in Denise Robinson, Through the Roadbloacks: Realities in Raw Motion, [Conference Reader], School of Fine Arts, Cyprus University, November 23–25, p. 94: it may be worth noting that the Ministry of Culture estimates that 80 percent of Iraqi artists are now living in exile, See: Art AsiaPacific Almanac, Volume 4, Art AsiaPacific, 2009, p. 75

- King, E.A. and Levi, G., Ethics and the Visual Arts, Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2010, pp 105-110

- Ettinghausen, E., Grabar, O. and Jenkins, M., Islamic Art and Architecture: 650-1250, Yale University Press, 2001, p. 79

- Hillenbrand, R., Islamic Art and Architecture, Thames & Hudson, [World of Art series], 1999, London, p. 59 ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7

- Dabrowska, K. and Hann, G., Iraq Then and Now: A Guide to the Country and Its People, Bradt Travel Guides, 2008, p. 278

- "Baghdad school," in: Encyclopædia Britannica, Online:

- "Baghdad school," in: Encyclopædia Britannica, Online:; Esanu, O., Art, Awakening, and Modernity in the Middle East: The Arab Nude, Routledge, 2017, [E-book edition], n.p.

- Wijdan, A. (ed.), Contemporary Art From The Islamic World,Scorpion, 1989, p.166

- "Baghdad school," in: Miriam Drake (ed), Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Volume 2, 2nd ed., CRC Press, 2003, p. 1259; Dimand, M.S., A Handbook of Mohammedan Decorative Arts, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1930, p. 20

- Frazier, I., "Invaders: Destroying Baghdad," New Yorker Magazine, [Special edition: Annals of History], April 25, 2005, Online Issue

- "Iraq, 1400–1600 A.D. | Chronology". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 45

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 46

- Tibi, B., Arab Nationalism between Islam and the Nation-state, 3rd edn., New York, Saint Martin's Press, 1997, pp. 49-49

- Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p.11

- Tejel, J., Writing the Modern History of Iraq: Historiographical and Political Challenges, World Scientific, 2012, p. 476

- Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p.199

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 47

- Sharifian, S., Mohammadzade, M., Naef, S. and Mehraee, M., "Cultural Continuity in Modern Iraqi Painting between 1950- 1980," The Scientific Journal of NAZAR Research Center (Nrc) for Art, Architecture & Urbanism, vol.14, no.47, May 2017, pp 43-54

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 47; Reynolds, D.F., The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p.199

- King, E.A. and Levi, G., Ethics and the Visual Arts, Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2010, p. 108

- "Iraq - The arts | history - geography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Altoma, S.J., "Postwar Iraqi Literature: Agonies of Rebirth", Books Abroad, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Spring, 1972), pp. 211-217 DOI: 10.2307/40126073

- Gohar, S.M., "Appropriating English Literature in Post-WWII Iraqi Poetry", The Victorian, vol. 5, no. 2. 2017, pp 10-22

- Ghareeb, E.A. and Dougherty, B., Historical Dictionary of Iraq, Scarecrow Press, 2004, p. 184

- Longrigg, S. and Stoakes, F., "The Social Pattern," in: Abdulla M. Lutfiyya and Charles W. Churchill (eds), Readings in Arab Middle Eastern Societies and Cultures, p. 78

- Sheehan, T., Photography, History, Difference, Dartmouth College Press, 2014, pp 63-64

- Kalash, K., "In Digital Technology, Solar Photography is a Time-immemorial Profession, " Iraq Journal,; also reproduced in: Alahad News, 26 May 2016 Online: Archived October 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine (translated from Arabic)

- "The First Photographers in Iraq ...And Why the Solar Photographer Disappeared", Iraq Journal, no. 369, 19 Jun. 2017, http://journaliraq.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/PAGE-9-1-12.pdf

- Bell, G., The Letters of Gertrude Bell, Vol. 2 (1927), Project Gutenberg edition, 2004, Online:

- "The First Photographers", Iraq National Library and Archives, Online: Archived March 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (translated from Arabic)

- El-Hagem B., "The Armenian Pioneers of Middle Eastern Photography," Palestine Studies, pp 22-26, Online:

- Alaq, A., "The Origins of Photography in Iraq", Arab Pictures, 24 December 2015, Online: (translated from Arabic)

- Gronlund, M., "How Latif Al Ani Captured Iraq’s Golden Era through a Lens," The National, 6 May 2018, Online:

- Al-Dabbagh, S., "Photographing Against the Grain: A History of Photography," Part I, Contemporary Practices, vol. 5, pp 40-51 Online:

- Munif, A.R., "The Monument of Freedom," The MIT Electronic Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Spring, 2007, p. 145

- Elsheshtawy, Y. (ed), Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An Urban Kaleidoscope, Routledge, 2004, p. 72

- Pieri, C., "Baghdad 1921-1958. Reflections on History as a ”strategy of vigilance”," Mona Deeb, World Congress for Middle-Eastern Studies, Jun 2005, Amman, Jordan, Al-Nashra, vol. 8, no 1-2, pp.69-93, 2006; Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 80; Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, pp 80-81

- Cited in Pieri, C., " Modernity and its Posts in constructing an Arab capital.: Baghdad’s urban space and architecture, context and questions," Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, The Middle East Studies Association of North, 2009, Vol. 42, No. 1-2, pp.32-39, <halshs-00941172>

- Iraqi art at archINFORM

- Bernhardsson, M.T., "Visions of the Past: Modernizing the Past in 1950s Baghdad," in Sandy Isenstadt and Kishwar Rizvi, Modernism and the Middle East: Architecture and Politics in the Twentieth Century, University of Washington Press, 2008, p.92

- Pieri, C., "Baghdad 1921-1958. Reflections on History as a ”strategy of vigilance”," Mona Deeb, World Congress for Middle-Eastern Studies, Jun 2005, Amman, Jordan. Al-Nashra, vol. 8, no 1-2, pp.69-93, 2006

- Selim, L., in correspondence with website by author of Memories of Eden, Online:; Tabbaa, Y. and Mervin, S., Najaf, the Gate of Wisdom, UNESCO, 2014, p. 69

- Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 95

- Chadirji, R., The Photographs of Kamil Chadirji: Social Life in the Middle East, 1920-1940, London, I.B. Tauris, 1995

- Uduku, O. Stanek, L., al-Silq, G., Bujas, P. and Gzowska, A., Architectural Pedagogy in Kumasi, Baghdad and Szczecin, in: Beatriz Colomina and Evangelos KotsiorisRadical Pedagogies, 2015

- Shabout, N.M., Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, University of Florida Press, 2007, p. 28

- Zuhur, D., Images of Enchantment: Visual and Performing Arts of the Middle East, American University in Cairo Press, 1998, p. 169

- Salīm, N., Iraq: Contemporary Art, Volume 1, Sartec, 1977, p. 6

- Greenberg, N., "Political Modernism, Jabrā, and the Baghdad Modern Art Group," CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2010, Online: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1603&context=clcweb, DOI: 10.7771/1481-4374.160; Floyd, T., "Mohammed Ghani Hikmat," [Biographical Notes] in: Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Islamic World, Online: http://www.encyclopedia.mathaf.org.qa/en/bios/Pages/Mohammed-Ghani-Hikmat.aspx

- Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, pp 97-98

- al-Kalil, S., Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq. Berkeley, University of California Press, pp 72-75

- Shabout, N., "The "Free" art of Occupation: Images for a "New" Iraq," Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 3/4 2006, pp. 41-53

- Brown, B.A. and Feldman, M.H. (eds), Critical Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Art,Walter de Gruyter, 2014 p.20

- Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017 pp 115-119; Anima Gallery, "Madiha Omar," [Biographical Notes], Online: https://www.meemartgallery.com/art_resources.php?id=89 Archived May 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5; Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56; Dadi. I., "Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective," South Atlantic Quarterly, 109 (3), 2010 pp 555-576, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-2010-006

- Lack, J., Why Are We 'Artists'?: 100 World Art Manifestos, Penguin UK, 2017, e-book edition, n.p. see Manifestos M12, M41 and M52

- Naef, S., “Not Just for Art’s Sake: Exhibiting Iraqi Art in the West after 2003 in:Jordi Tejel, Peter Sluglett and Riccardo Bocco (eds), Writing the Modern History of Iraq: Historiographical and Political Challenges, World Scientific, 2012 , p. 497

- Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 79 -80

- Al-Ali, N. and Al-Najjar, D., We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War, Syracuse University Press, 2013, p. 22

- Davis, E., Memories of State: Politics, History, and Collective Identity in Modern Iraq, University of California Press, 2005, p. 82; Kohl, P.L. Kozelsky, M., Ben-Yehuda, N. (eds), Selective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National Pasts, University of Chicago Press, 2008, p. 199

- Kohl, P.L. Kozelsky, M., Ben-Yehuda, N. (eds), Selective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National Pasts, University of Chicago Press, 2008, pp 199-200

- Sabrah,S.A. and Ali, M.," Iraqi Artwork Red List: A Partial List of the Artworks Missing from the National Museum of Modern Art, Baghdad, Iraq, 2010, pp 7-9

- Dabrowska, K. and Hann, G., Iraq: The Ancient Sites and Iraqi Kurdistan, Bradt Travel Guides, 2015, p. 30

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p.51

- Baram, A., Culture, History and Ideology in the Formation of Ba'thist Iraq,1968-89, Springer, 1991, pp 69-70; Shabout, N.,"Shakir Hassan Al Said: Time and Space in the Work of the Iraqi Artist - A Journey Towards One Dimension," Nafas Art Magazine, May 2008, Online:; Lack, J., Why Are We 'Artists'?: 100 World Art Manifestos, Penguin, 2017, [E-book edition], n.p. See section M52

- Baram, A., "Culture in the Service of Wataniyya: The Treatment of Mesopotamian Art," Asian and African Studies, Vol. 17, Nos. 1-3, 1983, p. 293

- Al-Khamis, U. (ed.), "An Historical Overview: 1900s-1990s," in: Strokes of Genius: Contemporary Iraqi Art, London, Saqi Books, 2001

- Baram, A., Culture, History and Ideology in the Formation of Ba'thist Iraq,1968-89, Springer, 1991, pp 70-71

- Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S. (eds), Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 141

- Ulrike al-Khamis, “An Historical Overview 1900s-1990s,” in: Maysaloun, F. (ed.), Strokes of Genius: Contemporary Iraqi Art, London:, Saqi Books, 2001, p. 25; Baram, A., Culture, History and Ideology in the Formation of Ba'thist Iraq, 1968-89, Springer, 1991, pp 70-71

- Shabout, N., "Jewad Selim: On Abstraction and Symbolism," in Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Arab World, Online: http://www.encyclopedia.mathaf.org.qa/en/essays/Pages/Jewad-Selim,-On-Abstraction-and-Symbolism.aspx

- Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 80

- Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, pp 80-81

- Baram, A., Culture, History and Ideology in the Formation of Ba'thist Iraq, 1968-89, Springer, 1991, pp 70-71

- Dougherty, B.K. and Ghareeb, E.A., Historical Dictionary of Iraq, Scarecrow Press, 2013, p. 495; Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 95

- Baram, A., Culture, History and Ideology in the Formation of Ba'thist Iraq, 1968-89, Springer, 1991, p. 69; Dougherty, B.K. and Ghareeb, E.A., Historical Dictionary of Iraq, Scarecrow Press, 2013, p. 495; Al-Khalil, S. and Makiya, K., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Iraq, University of California Press, 1991, p. 95

- Salīm, N., Iraq: Contemporary Art, Volume 1, Sartec, 1977, p. 7

- Lack, J., Why Are We 'Artists'?: 100 World Art Manifestos, Penguin, 2017, [E-book edition], n.p. See section M12

- Dabrowska, K. and Hann, G., Iraq Then and Now: A Guide to the Country and Its People, Bradt Travel Guides, 2008, p. 278; Faraj, M., Strokes Of Genius: Contemporary Iraqi Art, London, Saqi Books, 2001, p. 43

- Shabout, N., "Ghosts of Futures Past: Iraqi Culture in a State of Suspension," in Denise Robinson, Through the Roadbloacks: Realities in Raw Motion, [Conference Reader], School of Fine Arts, Cyprus University, November 23–25

- Al-Haydari, B., "Jawad Salim and Faiq Hasan and the Birth of Modern Art in Iraq," Ur, Vol. 4, 1985, p. 17

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, pp 50-51; Dabrowska, K. and Hann, G., Iraq Then and Now: A Guide to the Country and Its People, Bradt Travel Guides, 2008, p. 279

- Pocock, C., "The Reason for the Project Art in Iraq Today", in: Azzawi, D. (ed.), Art in Iraq Today, Abu Dhabi, Skira and Meem, 2011, p. 101

- Bahrani, Z. and Shabout, N.M., Modernism and Iraq, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York, 2009, p.94

- "Profile: Faik Hassan," Al Jazeera, 31 October 2005, Online"; Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S. (eds), Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 141; Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 52

- Ministry of Culture and Arts, Culture and arts in Iraq: Celebrating the Tenth Anniversary of the July 17–30 Revolution, The Ministry, Iraq, 1978, p. 26

- Ghareeb, E.A. and Dougherty, B., Historical Dictionary of Iraq, Scarecrow Press, 2004, p. 174

- Saad, Q., "Contemporary Iraqi Art: Origins and Development," Scope vol. 3, November, 2008, p. 54

- Shabout, N.,"Shakir Hassan Al Said: Time and Space in the Work of the Iraqi Artist - A Journey Towards One Dimension," Nafas Art Magazine, May 2008, Online:

- Lack, J., Why Are We 'Artists'?: 100 World Art Manifestos, Penguin, 2017, [E-book edition], n.p. See section M52; Shabout, N.,"Shakir Hassan Al Said: Time and Space in the Work of the Iraqi Artist - A Journey Towards One Dimension," Nafas Art Magazine, May 2008, Online:

- Lindgren, A. and Ross, S., The Modernist World, Routledge, 2015, p. 495; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/; Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56; Flood, F.B. and Necipoglu, G. (eds) A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, Wiley, 2017, p. 1294; Mejcher-Atassi, S., "Shakir Hassan Al Said," in Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Arab World, Online: http://www.encyclopedia.mathaf.org.qa/en/bios/Pages/Shakir-Hassan-Al-Said.aspx

- Lindgren, A. and Ross, S., The Modernist World, Routledge, 2015, p. 495; Mavrakis, N., "The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art," McGill Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Blog, Online: https://mjmes.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/article-5/; Tuohy, A. and Masters, C., A-Z Great Modern Artists, Hachette UK, 2015, p. 56

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997, p. 52

- Baram A., "Art With Local and Mesopotamian Components," in: Culture, History and Ideology in the Formation of Ba‘thist Iraq, 1968–89, [St Antony’s/Macmillan Series], London, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1991, p. 280

- Treichl, C., Art and Language: Explorations in (Post) Modern Thought and Visual Culture, Kassel University Press, 2017, p.117

- Shabout, N., "Ghosts of Futures Past: Iraqi Culture in a State of Suspension," in Denise Robinson, Through the Roadbloacks: Realities in Raw Motion, [Conference Reader], School of Fine Arts, Cyprus University, November 23–25, pp 95- 96; Farrell, S., "With Fixtures of War as Their Canvas, Muralists Add Beauty to Baghdad," New York Times, August 11, 2007, Online:; Al-Ali, N. and Al-Najjar, D., We Are Iraqis: Aesthetics and Politics in a Time of War, Syracuse University Press, 2013 p. 15

- Murphy, B., "Artists resist pressure to be more sectarian," Associated Press and Charlotte Observer, July 26, 2008 Online:

- "Profile: Faik Hassan - Al Jazeera English". Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Kember, Pamela (2013). Benezit Dictionary of Asian Artists. Oxford University Press.

- Kahalid al-Kishtyan in 1981, cited in: Baram, A., "Culture in the Service of Wataniyya: The Treatment of Mesopotamian Art," Asian and African Studies, Vol. 17, Nos. 1-3, 1983, pp 265-309 and in Baram, A., Culture, History and Ideology in the Formation of Ba'thist Iraq,1968-89, Springer, 1991, p. 69

- Shabout, N., "The Preservation of Iraq's Modern Heritage in the Aftermath of the US Invasion of 2003," in: Elaine A. King and Gail Levin (eds), Ethics And the Visual Arts, New York, Allworth, 2006, p. 109

- Shabout, N., "The Preservation of Iraq's Modern Heritage in the Aftermath of the US Invasion of 2003," in: Elaine A. King and Gail Levin (eds), Ethics And the Visual Arts, New York, Allworth, 2006, pp 105 -120; Sabrah, S.A. and Ali, M., "Iraqi Artwork Red List: A Partial List of the Artworks Missing from the National Museum of Modern Art", Baghdad, Iraq, 2010, pp 4-5

- Shabout, N., "The Preservation of Iraq's Modern Heritage in the Aftermath of the US Invasion of 2003," in: Elaine A. King and Gail Levin (eds), Ethics And the Visual Arts, New York, Allworth, 2006, pp 109-110

- Shabout, N., "Ghosts of Future Pasts: Iraq in a State of Suspension," in: Through the roadblocks: Realities in Raw Motion: Conference Reader, School of Fine and Applied Arts, Cyprus University, November 23–25, 2012, pp 89-102

- Art AsiaPacific Almanac, Volume 4, Art AsiaPacific, 2009, p. 75

- Hope, B., "Iraqi Art - in New York," New York Sun, March 3, 2006; Riccardo, B., Hamit, B. and Sluglett, P., Writing the Modern History Of Iraq: Historiographical And Political Challenges,World Scientific, 2012 pp 490-93

- Rellstab, F.H. and Schlote, C., Representations of War, Migration, and Refugeehood: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Routledge, 2014, p. 76

- Asfahani, R., "Interview With Hanaa Malallah: Iraq’s Pioneering Female Artist," Culturetrip, 29 November 2016, Online.

- Shaheen, K., "Outcry over ISIS destruction of Ancient Assyrian site of Nimrud," The Guardian, March 7, 2015, Online:

- Wheeler, A., "Photos of Ancient Landmarks and World Heritage Sites Destroyed by Terrorist Groups," International Business Times, August 23, 2016, Online

- Cullinane, S., Alkhshali, H. and Tawfee, M., "Tracking a Trail of Historical Obliteration: ISIS Trumpets Destruction of Nimrud," CNN News, Online:

- MacDiarmid, Campbell. "Iraqi artist depicts life under ISIL". Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Shabout, N., "Ghosts of Futures Past: Iraqi Culture in a State of Suspension," in Denise Robinson, Through the Roadbloacks: Realities in Raw Motion, [Conference Reader], School of Fine Arts, Cyprus University, November 23–25, pp 94-95

- King, E.A. and Levi, G., Ethics and the Visual Arts, Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2010, p. 107

- King, E.A. and Levi, G., Ethics and the Visual Arts, Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2010, pp 107-108

- Naef, S., "Not Just for Art's Sake: Exhibiting Iraqi Art in the West after 2003," in: Bocco Riccardo, Bozarslan Hamit and Sluglett Peter (eds), Writing The Modern History Of Iraq: Historiographical And Political Challenges, World Scientific, 2012, p. 479; Hann, G., Dabrowska, K., Greaves, T.T., Iraq: The Ancient Sites and Iraqi Kurdistan, Bradt Travel Guides, 2015, p. 32

- Naef, S., "Not Just for Art's Sake: Exhibiting Iraqi Art in the West after 2003," in: Bocco Riccardo, Bozarslan Hamit and Sluglett Peter (eds), Writing The Modern History Of Iraq: Historiographical And Political Challenges, World Scientific, 2012, p. 479

- Hann, G., Dabrowska, K., Greaves, T.T., Iraq: The Ancient Sites and Iraqi Kurdistan, Bradt Travel Guides, 2015, p. 32

- Ruya Foundation, Ruya Shop: A Contemporary Art Space and Library in Baghdad, March 2, 2018

External links

- Virtual Museum of Iraq available in English, Arabic and Italian

Further reading

- Ali, W., Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997

- Bahrani, Z. and Shabout, N.M., Modernism and Iraq, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery and Columbia University, 2009

- Bloom J. and Blair, S., The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Oxford University Press, 2009 Vols 1-3

- Boullata, I. Modern Arabic Poets, London, Heinemann, 1976

- Faraj, M., Strokes Of Genius: Contemporary Art from Iraq, London, Saqi Books, 2001

- "Iraq: Arts" Encyclopædia Britannica, Online:

- Jabra, I.J., The Grass Roots of Art in Iraq, Waisit Graphic and Publishing, 1983, Online: Archived August 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Mathaf Encyclopedia of Modern Art and the Islamic World, Online:

- Reynolds, D.F. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015 ( Or Khoury, N.N.N. "Art" in Dwight, F. Reynolds (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Modern Arab Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp 191–208

- Sabrah, S.A. and Ali, M., Iraqi Artwork Red List: A Partial List of the Artworks Missing from the National Museum of Modern Art, Baghdad, Iraq, 2010

- Salīm, N., Iraq: Contemporary Art, Volume 1, Sartec, 1977

- Shabout, N., "The Preservation of Iraq's Modern Heritage in the Aftermath of the US Invasion of 2003," in: Elaine A. King and Gail Levin (eds), Ethics And the Visual Arts, New York, Allworth, 2006, pp 105 –120

- Schroth, M-A. (ed.), Longing for Eternity: One Century of Modern and Contemporary Iraqi Art, Skira, 2014

- Saad, Q., "Contemporary Iraqi Art: Origins and Development," Scope, [Special Issue: Iraqi Art] Vol. 3, November 2008 Online:

- Shabout, N.M., Modern Arab Art: Formation of Arab Aesthetics, University of Florida Press, 2007