Seventh cholera pandemic

The seventh cholera pandemic (also called by some the 1961–1975 cholera pandemic) is the seventh major outbreak of cholera and occurred principally from the years 1961 to 1975, but the strain involved persists to the present.[1] WHO and some other authorities believe this should be considered as an ongoing pandemic. As stated in its cholera factsheet dated 30 March 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) continues to define this outbreak as a current pandemic, and with cholera having become endemic in many countries. In 2017, WHO announced a global strategy aiming to end this pandemic by 2030.[2]

| seventh cholera pandemic | |

|---|---|

Cholera rehydration nurses | |

| Disease | Cholera |

| Bacteria strain | Vibrio cholerae biotype El Tor |

| Location | Asia, Africa, Europe, the Americas |

| First outbreak | Makassar, South Sulawesi |

| Arrival date | 1961 |

| Confirmed cases | 1,126,229 |

This pandemic is based on the strain called El Tor; it started in Indonesia in 1961 and spread to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), by 1963.[3] It went to India in 1964, and into the Soviet Union by 1966. In July 1970, there was an outbreak in Odessa (now Ukraine) and in 1972 there were reports of outbreaks in Baku, but the Soviet Union suppressed this information.[3] Cholera reached Italy in 1973 from North Africa. Japan and the South Pacific saw a few outbreaks by the late 1970s.[3] In 1971, the number of cases reported worldwide was 155,000. But in 1991, it reached 570,000.[1] The spread of the disease was helped by modern transportation and mass migrations. Mortality rates, however, dropped markedly as governments began modern curative and preventive measures. The usual mortality rate of 50% dropped to 10% by the 1980s and less than 3% by the 1990s.[1]

In 1991, the strain made a comeback in Latin America. It began in Peru, where it killed roughly 10,000 people.[4] Research has traced the origin of the strain to the seventh cholera pandemic.[5] Researchers initially suspected the strain came to Latin America through Asia from contaminated water, but samples from Latin America and samples from Africa were found to be identical.[6]

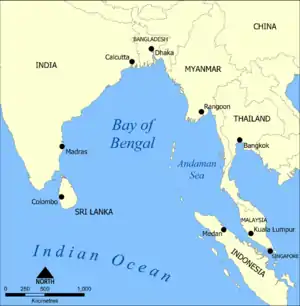

This rapid transmission of the pathogen around the globe in the 20th century can be attributed chiefly to the major hub, the Bay of Bengal, from where the disease spread.

This pandemic can be categorized into two main periods. During Period 1 (1961–1969), 24 Asian countries reported 419,968 cholera cases. In Period 2 (1970–1975), 73 countries from Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas reported 706,261 cases.[7] Cholera is caused by eating food or drinking water that is contaminated with the bacteria V. cholerae. It affects both children and adults, causing severe watery diarrhea with dehydration. But, as noted, the El Tor strain has persisted for decades to the present, causing repeated epidemics in varied locations, with 570,000 cases in 1991 alone. WHO and other authorities believe that the seventh pandemic continues.

Introduction

Cholera is an acute diarrhoeal infection caused by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. Most commonly the contamination of food or water occurs via faecal matter, and the infection is spread through the faecal-oral route. Cholera has also been found to be caused by eating raw shellfish. Symptoms of the disease appear between 12 hours and 5 days of infection; however, only 10% of infected people show severe symptoms of watery diarrhoea, vomiting and leg cramps.[8] Cholera is diagnosed through a stool test or rectal swab, and today treatment takes the form of an oral rehydration solution (ORS). The ORS uses equimolar concentrations of sodium and glucose to maximise sodium uptake in the small intestine, and carefully replaces fluid losses.[9] In severe cases, the rapid loss of bodily fluids leads to dehydration and patients are at risk of shock. This requires administration of intravenous fluids and antibiotics.

The transmission of cholera is closely linked to inadequate access to clean water and sanitation facilities and hence, people at risk largely live in slums and poor communities.[10] In the spread of cholera from 1961 to 1975, other factors were identified that played a role in the cholera pandemic. Terrorism and disruption of social institutions, floods, improper sewage disposal, and a lack of environmental hygiene were the main causes of the spread.

Sources

The 7th pandemic is traced to early 1961. The evolution of the classical cholera strain known from the first six pandemics was revealed through genetic analysis. The first observation of the new lineage came from a laboratory in El Tor, Egypt, in 1897. By this time, the ‘El Tor’ strain differed from its relatives by 30%.[11] It originated in South-Asia, then transitioned to its non-pathogenic form in the Middle East in 1900. Sometime between 1903 and 1908, the El Tor strain picked up DNA that triggered its ability to cause disease in humans.[11] Hence, it had mutated into the El Tor pandemic strain.[12] Makassar, South Sulawesi was the source of a 1960 outbreak of the El Tor strain, where it gained new genes that likely increased transmissibility.[11] Cholera spread overseas in 1961, indicating a pandemic strain.

Many studies point to Indonesia as the source of the seventh cholera pandemic; however, research has indicated that outbreaks in China between 1960 and 1990 were associated with the same sub-lineages. These strains spread globally from the Bay of Bengal on multiple occasions.[13] China has been classified as both a sink and source during the pandemic spread of cholera throughout the 1960s and 1970s. The suggestion that the pandemic spread of cholera may have been augmented by Chinese cases, in addition to China being identified as an origin for bordering countries, contrasts with the view that the pandemic began in Indonesia.[13]

Spread and mortality

The El Tor cholera outbreak was first reported in Java, a seaside community near Kendal which was visited by travellers from Makassar in May 1961.[14] Shortly after, Semarang and Djakarta became infected in June.

The disease was carried into Kuching, Sarawak when boats from Celebes participated in a regatta in Kuching; the first cholera cases appeared on 1 July. This outbreak lasted two weeks, infecting 582 persons with 79 deaths (17% mortality). By August, the outbreak had reached Kalimantan and Macau (13 patients and six deaths). The first case in Hong Kong appeared on 15 August in a community near Kwangtung, a fishing area. The second case was from a boat-dwelling population located between Kwangtung and Hong Kong. Hong Kong had 72 cases with 15 deaths (20.8% mortality).[15]

By February 1, 1962, 4,107 people were infected with cholera, with 897 deaths (21.8% mortality). By September, despite a massive vaccination campaign, cholera had rapidly moved through the Philippines, where the number of infected people reached 15,000 by March 1962, with 2,005 deaths. In the Philippines alone, mortality reached 1,682 in 1962.[16] It was reintroduced into British Borneo, supposedly by an asymptomatic traveller from Jolo Island. Outbreaks subsequently occurred in Cambodia, Thailand, Singapore and India.[15]

In 1963, WHO declared that cholera remained the number-one killer in diseases subject to international quarantine, having been reported in Taiwan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Southern Russia, Iraq, Korea, Burma, Cambodia, South Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Nepal, Thailand, Uzbekistan and Hong Kong.[16]

The mid-60s saw cholera infiltrate Southeast Asia, with outbreaks in Chittagong, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Thailand and Malaysia, and India in 1964. The El Tor strain moved further westward, invading South Asia in 1965, including Pakistan, Nepal, Afghanistan, Iran and part of Uzbekistan SSR. Iran, which had been free from cholera since 1939, reported 2,704 cases by mid-October.[16] When these outbreaks occurred in Iran, the Pasteur Institute of Iran produced 9.5 million cholera vaccines to protect the population of the eastern regions of Iran.[17] In 1966 Iraq reported its first case.

The cholera strain reached the Middle East and Africa in 1970 and spread rapidly. It is thought that a traveler returning from Asia or the Middle East introduced the disease into Africa.[18] The Arabian Peninsula, Syria and Jordan became infected, followed by Guinea in August 1970. Cholera was first thought to have spread along waterways along the coast and into the interior along the rivers.

In November 1970 infected individuals seemed to travel by modernised rapid transport. This allowed cholera to extend 1,000 km, when it appeared in Mopti, Mali. Subsequently, customary large gatherings of people facilitated the outward radiation of cholera.[18] From 1970 to 1971, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria and southern Cameroon, experienced outbreaks. The west-African outbreak of cholera during 1970–1971 infected more than 400,000 persons.[19] Africa had a high cholera fatality rate of 16% by 1962. 25 countries were infected by the end of 1971 and, between 1972 and 1991, cholera spread throughout much of the remainder of Africa.[18]

Research

An international campaign began in 1970, including the research laboratory in Dhaka, Bangladesh; the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation (SEATO), the United Kingdom, Australia, and various American agencies. Human volunteers took part in an NIH-sponsored series of tests to develop an effective cholera vaccine. At this time, new outbreaks of cholera were occurring in Egypt, South Korea, and the Soviet Union.[16]

The 1964 invention of use of oral rehydration salts (ORS) to treat cholera was endorsed by WHO in the 1980s. This practice of replacing fluids and electrolytes is estimated to have saved the lives of 40 million individuals infected with cholera. As a result of the success of ORS treatment, the past 30 years have seen changes to cholera response that centred on treating affected individuals in the short term, and attempting to provide safe water and improved hygiene in the long term.[20]

The cholera pandemic beginning in 1962 is identified through the ‘El Tor’ biotype, and considerable research has been undertaken into this specific strain of cholera. The El Tor biotype has been demonstrated to have increased resistance to the environment.[20] This has heightened the risk of unknowing transmission from asymptomatic carriage in humans, as opposed to the classical biotype that caused the first six cholera pandemics.

Previously, health workers who were against the administration of the cholera vaccine based their opinion on the view that always limited resources should be directed at immediate rehydration and improved practices, and longer term investment to provide safe water and improved sanitation. Such practices as appropriately cooking food before consumption, using sterilised water, following general personal hygiene, and sanitising environments, decrease the spread of cholera.[21] In the 21st century, cholera control activities have typically still been focused on emergency responses to outbreaks, with limited attention to the underlying causes that can prevent recurrence.[22]

But, the development of new and improved cholera vaccines has allowed this practice of emergency responses to be revised.[20] In addition, recent research has advanced understanding of cholera, its transmission and the immune response. Subsequently, these advances have resulted in the development of experimental cholera vaccines derived from non-living and attenuated live strains.[23] By 2017 the FDA had approved a single-dose, live, oral cholera vaccine called Vaxchora for adults aged 18–64 who are travelling to an area of active cholera transmission.[24] A study in Haiti has shown lasting protection from a two-dose cholera vaccine. During the 2010–2017 cholera outbreak in Haiti, those who received the two doses of the vaccine were 76% less likely to become sick. This protection lasted 4 years.

The clinical severity of the El Tor biotype causing pandemic cholera in 1962, also resulted in modern research assessing administration of antimicrobials in the initial phase of an outbreak. This was tested in the 1970s with tetracycline but was found not to be useful due to resistance against this antibiotic.[25] Questions have been raised alluding to newer drugs, and whether the administration of these will be more useful than such previous attempts.[20]

The ongoing seventh pandemic has affirmed that cholera is still prevalent in society and can cause high mortality. In 1992 the Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC) was organized to coordinate activities and support countries after a severe cholera outbreak in Peru. Today it consists of more than 30 collaborating institutions, including NGOs, academic institutions, and UN agencies supporting affected countries.[26] In 2017 they convened a high-level meeting with officials from cholera-affected countries, donors, and technical partners to announce their strategy “The Global Roadmap to 2030”, an initiative to end cholera as a threat to public health by 2030. The three components of the strategy are: “early detection and quick response to contain the outbreaks; a multi-sectorial {sic} approach to prevent cholera recurrence, and, coordination of technical support and advocacy, resource mobilisation and partnership at the global level.[22]

References

- Hays JN (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. ABC-CLIO. p. 421. ISBN 9781851096589.

%22Seventh%20Cholera%20pandemic%22.

- "Cholera factsheet" (Press release). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Ahiarah L (6 May 2008). "Cholera". www.austincc.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-10-15. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Cholera's seven pandemics". www.cbc.ca. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- "Global epidemics and impact of cholera". www.who.int. Archived from the original on January 26, 2005. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- Lam C, Octavia S, Reeves P, Wang L, Lan R (July 2010). "Evolution of seventh cholera pandemic and origin of 1991 epidemic, Latin America". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (7): 1130–2. doi:10.3201/eid1607.100131. PMC 3321917. PMID 20587187.

- Narkevich MI, Onischenko GG, Lomov JM, Moskvitina EA, Podosinnikova LS, Medinsky GM (1993). "The seventh pandemic of cholera in the USSR, 1961-89". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 71 (2): 189–96. PMC 2393457. PMID 8490982.

- "General Information | Cholera | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-12-13. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Qadri F, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB (June 2012). "Cholera". Lancet. 379 (9835): 2466–2476. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60436-X. PMC 3761070. PMID 22748592.

- "Cholera". www.who.int. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Shultz D (18 November 2016). "How today's cholera pandemic was born". Science. AAAS. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Hu D, Liu B, Feng L, Ding P, Guo X, Wang M, et al. (November 2016). "Origins of the current seventh cholera pandemic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (48): E7730–E7739. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E7730H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1608732113. PMC 5137724. PMID 27849586.

- Didelot X, Pang B, Zhou Z, McCann A, Ni P, Li D, et al. (March 2015). "The role of China in the global spread of the current cholera pandemic". PLOS Genetics. 11 (3): e1005072. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005072. PMC 4358972. PMID 25768799.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (1962). "Meeting for the Exchange of Information on El Tor Vibrion Paracholera, Manila, Philippines, 16-19 April 1962 : final report".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Felsenfeld O (1963). "Some observations on the cholera (E1 Tor) epidemic in 1961-62". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 28 (3): 289–96. PMC 2554714. PMID 13962884.

- Kotar SL, Gessler JE (3 March 2014). Cholera : a worldwide history. Jefferson, North Carolina. ISBN 978-0-7864-7242-0. OCLC 853310469.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Azizi M, Azizi F (January 2010). "History of Cholera Outbreaks in Iran during the 19(th) and 20(th) Centuries". Middle East Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2 (1): 51–5. PMC 4154910. PMID 25197514.

- Swerdlow DL, Isaäcson M (1994-01-01). "Chapter 19 : The Epidemiology of Cholera in Africa". In Wachsmuth IK, Blake PA, Olsvik Ø (eds.). Vibrio cholerae and Cholera. American Society of Microbiology. pp. 297–307. doi:10.1128/9781555818364.ch19. ISBN 978-1-55581-067-2.

- Nair GB, Takeda Y, eds. (2014). "Cholera Outbreaks". Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 379. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55404-9. ISBN 978-3-642-55403-2. ISSN 0070-217X. S2CID 44643420.

- Ryan ET (January 2011). "The cholera pandemic, still with us after half a century: time to rethink". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 5 (1): e1003. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001003. PMC 3026764. PMID 21283611.

- Idoga PE, Toycan M, Zayyad MA (June 2019). "Analysis of Factors Contributing to the Spread of Cholera in Developing Countries". The Eurasian Journal of Medicine. 51 (2): 121–127. doi:10.5152/eurasianjmed.2019.18334. PMC 6592437. PMID 31258350.

- Somboonwit C, Menezes LJ, Holt DA, Sinnott JT, Shapshak P (2017-12-31). "Current views and challenges on clinical cholera". Bioinformation. 13 (12): 405–409. doi:10.6026/97320630013405. PMC 5767916. PMID 29379258.

- "Recent advances in cholera research: memorandum from a WHO meeting". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 63 (5): 841–9. 1985. hdl:10665/49855. PMC 2536442. PMID 3879198.

- "Cholera Fact Sheet". www.health.ny.gov. 2017. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Chopra I, Roberts M (June 2001). "Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 65 (2): 232–60, second page, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. PMC 99026. PMID 11381101.

- "Global Task Force on Cholera Control". GTFCC. 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2022.