Hong Kong flu

The Hong Kong flu, also known as the 1968 flu pandemic, was a flu pandemic whose outbreak in 1968 and 1969 killed between one and four million people globally.[1][2][3][4][5] It is among the deadliest pandemics in history, and was caused by an H3N2 strain of the influenza A virus. The virus was descended from H2N2 (which caused the Asian flu pandemic in 1957–1958) through antigenic shift, a genetic process in which genes from multiple subtypes are reassorted to form a new virus.[6][7][8]

| Hong Kong flu | |

|---|---|

| Disease | Influenza |

| Virus strain | H3N2 strain of Influenza A virus |

| Dates | 1968–1969 |

Deaths | between 1 and 4 million |

| Fatality rate | 0.2% |

History

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

Origin and outbreak in Hong Kong and China

The first recorded instance of the outbreak appeared on 13 July 1968 in British Hong Kong.[8][9][10][11] It has been speculated that the outbreak began in mainland China before it spread to Hong Kong;[10] On 11 July, before the outbreak in the colony was first noted, the Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao reported an outbreak of respiratory illness in Guangdong Province,[12] and the next day, The Times issued a similar report of an epidemic in southeastern China.[13] Later reporting suggested that the flu had spread from the central provinces of Sichuan, Gansu, Shaanxi, and Shanxi, which had experienced epidemics in the spring.[14] However, due to a lack of etiological information on the outbreak and a strained relationship between Chinese health authorities and those in other countries at the time, it cannot be ascertained whether the Hong Kong virus was to blame.[13]

The outbreak in Hong Kong, where the population density was greater than 6,000 people per square kilometre (20,000 per sq. mi.), reached its maximum intensity in two weeks.[10][11] The outbreak lasted around six weeks, affecting about 15% of the population (some 500,000 people infected), but the mortality rate was low and the clinical symptoms were mild.[10][11][9][15]

There were two waves of the flu in mainland China, one between July–September in 1968 and the other between June–December in 1970.[15] The reported data were very limited due to the Cultural Revolution, but retrospective analysis of flu activity between 1968 and 1992 shows that flu infection was the most serious in 1968, implying that most areas in China were affected at the time.[15]

Outbreaks in other areas

Despite the lethality of the 1957–1958 pandemic in China, little improvement had been made regarding the handling of such epidemics.[11]

By 13 August, it was clear to virologists that strains isolated from the outbreak in Hong Kong differed markedly from previous strains of influenza.[16] However, they were not at the time considered to be an entirely new subtype of influenza A, only a variant of older strains.[17] Nevertheless, the World Health Organization warned of potential worldwide spread of the virus on 16 August.[10] An outbreak of influenza-like illness in Singapore during the second week of August was the first indication of spread outside of Hong Kong.[17] Around the same time, an outbreak became apparent in the Philippines[18] and Malaysia,[19] and, before the end of the month, an epidemic was underway in the Republic of Vietnam.[20]

The first known cases of the flu in the United Kingdom were identified in early August in an infant and her mother in London with no history of travel or known contact with anyone with a history of travel from the Far East. More isolated cases soon followed, but it was not until September that larger outbreaks began occurring in school settings.[21]

In September 1968, the flu reached India,[22] northern Australia,[23] Thailand,[24] and Europe. The same month, the virus entered the United States and was carried by troops returning from the Vietnam War, but it did not become widespread in the country until December 1968.

During the second week of September, nearly 2000 participants from 92 countries, including some in southeast Asia where the flu was epidemic, met in Tehran for the Eighth International Congresses on Tropical Medicine and Malaria.[25] An outbreak of influenza soon erupted among the participants, afflicting at least a third of them.[26] The convention was the apparent origin of a broader outbreak within the capital city, which thereafter spread rapidly throughout Iran.[27][20]

The virus entered Japan repeatedly throughout August and September, but these introductions did not spark any larger outbreak. The first "true epidemic" began in early October, almost entirely confined to school settings.[28]

In the USSR, the first cases of the flu began to appear in mid-December.[29]

It reached Africa and South America by 1969.[30]

The development of the pandemic at first resembled that of the 1957 pandemic, which had spread unencumbered throughout the spring and summer and had become truly worldwide by October, by which point nearly all countries were experiencing their first or even second wave.[31][32] However, the two experiences eventually diverged within a couple of months after their initial outbreaks. In 1968, many countries (e.g., the UK, Japan) did not immediately see outbreaks despite repeated introductions of the virus throughout August and September. Additionally, after September, there was little evidence of continued spread in new areas, despite similar importations of the virus into those areas. Epidemics did eventually develop during the winter months, but these were often mild (especially when compared to the US experience).[13] In some countries (such as the UK and Japan), it was not until the following winter of 1969–1970 that truly severe epidemics developed.[33]

At the time of the outbreak, the Hong Kong flu was also known as the "Mao flu" or "Mao Tse-tung flu".[34][35][36][37] The name "Hong Kong flu" was not used within the colony, where the press dubbed it the "killer flu" after the first several deaths.[14] Before the end of July, the South China Morning Post predicted that "Fingers of scorn" would be directed at Hong Kong in the coming weeks and stated that the colony had "acted, unwillingly, in our old role as an entrepot for a sneeze".[12] (An outbreak of influenza in Hong Kong had been the first one to occur outside of mainland China during the 1957–1958 pandemic and had been what alerted the rest of the world to the developing situation, when international press began to report on it.)[38]

A city councillor later decried the widespread adoption of the name "Hong Kong flu", claiming that it was "giving Hong Kong a bad name". He asked why foreign press and health authorities did not refer to it by its "proper name—China flu".[14] China certainly did not escape associations with the new virus, however, as the name "Mao flu" suggests. It was speculated even at the time that the virus had originated from "Red China".[14] These differing names for the flu resulted in some confusion: In January 1969, a British member of parliament asked David Ennals, the Secretary of State for Social Services, "in what way the characteristics of Mao flu can be distinguished from those of Hong Kong flu".[39] In addition to these names, the virus was also often referred to as "Asian flu" or "Asiatic flu",[40][41] as it was not yet considered an entirely different subtype from the previously circulating influenza A.

Worldwide deaths from the virus peaked in December 1968 and January 1969, when public health warnings[42] and virus descriptions[43] had been widely issued in the scientific and medical journals. Isolated countries like Albania reported the first cases of the flu in December 1969, reaching a peak in infections in the first months of the year 1970.[44] In Berlin, the excessive number of deaths led to corpses being stored in subway tunnels, and in West Germany, garbage collectors had to bury the dead because of a lack of undertakers. In total, East and West Germany registered 60,000 estimated deaths. In some areas of France, half of the workforce was bedridden, and manufacturing suffered large disruptions because of absenteeism. The UK postal and rail services were also severely disrupted.[45]

United States

After a major epidemic of H2N2 during the 1967–1968 flu season that resulted in outbreaks in all but four states, the Communicable Disease Center (today the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in June 1968 forecasted little or no activity in 1968–1969. The vaccines for the upcoming season would incorporate the then-circulating seasonal flu strains, and the CDC's recommendations for their use extended mainly to individuals in older age groups (over the age of 45) and the chronically ill.[46]

Following the outbreak in Hong Kong and the recognition that it had been caused by a new variant of influenza, the CDC on 4 September revised its prediction for the 1968–1969 season. An extensive outbreak across the country was now more likely. It repeated more strongly its recommendation that existing vaccines go only to those at highest risk and recommended vaccinating or revaccinating this group once the monovalent vaccine specific to the new variant became available.[47]

The first cases of the virus were reported in Atlanta on 2 September.[48] The first was a Marine Corps major returning from Vietnam,[49] who fell ill four days after arriving back in the US. Two days later, his wife, who had not left the country, fell ill as well.[48] The first outbreak occurred in a Marine Corps school in San Diego that same week. Before the end of the week, influenza surveillance was heightened all across the country, and summaries of the data were thereafter reported regularly by the CDC each week in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Further outbreaks among military personnel with connections to southeast Asia were soon to follow during the middle of September.[49]

Isolated cases, mostly in those recently returning from the Far East, seeded the virus across the country throughout September. The first outbreaks in the civilian population occurred in late September and in October, and activity increased markedly throughout November, affecting 21 states by Thanksgiving.[49]

The epidemic became widespread in December, involving all 50 states before the end of the year.[49] Outbreaks occurred in colleges and hospitals, in some places the disease attacking upwards of 40% of their populations. Reports of absenteeism among students and nurses grew. Schools in Los Angeles, for example, reported rates ranging from 10 to 25%, compared to a typical 5 or 6%.[50] The Greater New York Hospital Association reported absenteeism of 15 to 20% among staff and urged its members to impose visitor restrictions to safeguard patients.[51]

Institutions in many states dismissed their students early for the holidays.[52] In New York and many other areas, holiday sales suffered mid-December, which affected retailers blamed on the flu epidemic (though inflation could have contributed to this as well).[53] Economic activity was also hampered by high levels of industrial absenteeism.[51][49]

On 18 December, it was reported that President Johnson had been hospitalized at Bethesda Naval Hospital with flu-like symptoms,[54] but whether the new variant was the cause of his illness was not made clear. He returned to the White House on 22 December.[55] Vice President Humphrey was also reported to be ailing from the flu on the day Johnson's condition was revealed.[54] Flu-like illness kept other senior governmental officials from their posts around this time, such as National Security Advisor Walt Rostow, Deputy White House Press Secretary Tom Johnson, and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Earle Wheeler.[56] On 23 December, it was reported that President-elect Nixon had been ill with the flu at his daughter's wedding the day before.[57] Nixon later claimed that "the wedding cured the flu."[58]

Peak influenza activity for most states most likely occurred in the latter half of December or early January, but the exact week was impossible to determine due to the holiday season. Activity declined throughout January. Excess pneumonia-influenza mortality passed the epidemic threshold during the first week of December and increased rapidly over the next month, peaking in the first half of January. It took until late March for mortality to return to normal levels. There was no second wave during this season.[49]

Following the epidemic of influenza A, outbreaks of influenza B began in late January and continued until late March. Mostly elementary-school children were affected.[49] This influenza B activity fit within the pattern of epidemics every three to six years, but the 1968–1969 flu season became the first documented instance of two major influenza A epidemics to occur in successive seasons.[59]

Given the widespread epidemic levels of influenza A activity in 1968–1969, the CDC in June 1969 predicted little more than "sporadic cases" of influenza A in the 1969–1970 season.[60] Influenza activity was indeed less than the preceding season, but there was "considerably more" than expected. The flu affected 48 states the following season but was widespread in only six, compared to 44 out of the 50 states in which activity was reported in 1968–1969.[61]

In October 1969, the CDC, alongside Emory University, collaborated with the WHO to host an international conference on the novel influenza in Atlanta. A wide range of topics was discussed, including the origin and path of the pandemic, the experiences of individual countries, and effective control measures, such as vaccination.[62]

Vaccine

It became apparent once the extent of antigenic variation in the virus was recognized that a new vaccine would be needed to protect against it.[47] However, production of the previously recommended vaccines in the US had concluded by July 1968, and supply of fertilized chicken eggs, in which flu vaccines are grown, was limited.[63] The first cultures of the virus were provided to manufacturers in August by the Division of Biologics of the National Institutes of Health for preliminary study. A strain isolated in Japan was sent to the US and, after showing greater potential for vaccine production, was given to manufacturers on 9 September.[38]

In 1968, American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman was head of the virus and vaccination research programs at the pharmaceutical firm Merck & Co., one of the licensed vaccine manufacturers in the US. Hilleman, as the director of the Department of Respiratory Diseases at the Army Medical School (now the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research), had foreseen the 1957 pandemic and kickstarted vaccine production then.[64] He was similarly instrumental in the development of the 1968 pandemic vaccine and, with the use of the Japanese strain, helped initiate early production.[64][63] Merck would go on to produce over 9 million of the nearly 21 million doses of vaccine produced.[65][38] The other half was produced together by Eli Lilly & Co., Lederle Laboratories, Parke Davis & Co., the National Drug Company, and Wyeth Laboratories.[63] All of these except Wyeth had been involved in the production of the 1957 vaccine.[66]

On 15 November, 66 days after the production strain became available, the first batch of 110,000 doses of vaccine was released, most of which went to the Armed Forces.[67][38] This represented a quicker turnaround than the release of the first doses of the 1957 vaccine, which took three months after its production strain became available. At this time, the flu was spreading fast around the country. There was much interest within the press and among public figures in the vaccine.[38] On 18 November, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association announced that 17.5 million doses would be available for civilian use but said that "substantial quantities" would only come after the New Year.[67] By the end of the year, over 10 million doses had been released.[38] At this point, influenza was widespread in the country.

Notably, the crew of Apollo 8 received the vaccine on 3 December prior to their mission later in the month.[68] President Johnson received "two types" of vaccine prior to his bout of flu in December,[54] but it is not clear if one of these was the pandemic vaccine. Johnson, 60 at the time, was in poor health and had been hospitalized several times during his presidency.[54] He thus would have been prioritized for vaccine given the CDC recommendations, even outside of being the president.

Lots of vaccine continued to be released throughout January 1969, with nearly 21 million doses available by the end of the month. By this point, however, influenza activity and subsequent mortality had already peaked. Demand for the vaccine diminished and a considerable surplus remained. Given the time it took to build up antibodies, it is unlikely a significant number of people were effectively immunized to alter the course of the epidemic.[38] Hilleman himself would later acknowledge that the vaccine was "too little and too late" for most of the country.[69] However, it was estimated that a "considerably higher" proportion of the recommended priority group of older and chronically ill persons received the pandemic vaccine than in 1957.[38] Nevertheless, even after the debacle that was the vaccination effort in 1957, US health officials by 1968 still had "no meaningful information regarding [influenza vaccine's] actual distribution", such as "to what extent it actually reaches persons at highest risk."[70]

Following the epidemic in the US, leftover vaccine was made available for the southern hemisphere and parts of Europe where the main outbreak had not yet happened.[69] The Japanese strain of the new variant was incorporated into the bivalent vaccines recommended for the 1969–1970 flu season in the US.[60]

Outside the US, vaccination efforts were undertaken in many countries in anticipation of an epidemic. In contrast to US policy, Japan had, since 1963, carried out mass vaccination campaigns against influenza every year regardless of whether an epidemic was expected. This began with the immunization of all children in kindergartens and primary and secondary schools followed by the vaccination of those working in crowded conditions. Enough vaccine was produced each year to vaccinate about 24 million people (nearly a quarter of Japan's population at this time), and this became the goal in 1968, targeting the same priority groups as in a typical flu season.[71]

The same Japanese strain used for vaccine production in the US was immediately sent out to the seven manufacturing firms in Japan. It was soon decided a bivalent vaccine consisting of two parts the new variant and one part influenza B would be produced, in contrast to the US's use of monovalent vaccine. The objective was also set that enough vaccine to immunize about 12 million people would be produced by the end of October, with the hope of at least vaccinating children to guard against an epidemic developing out of schools. After some delay, the mass vaccination campaign was nearly completed before the end of the year.[71]

Yugoslavia received the Japanese strain in mid-October and immediately began experimental trials prior to large-scale production. During this time before the new vaccine was ready, 1.5 million doses of seasonal influenza A vaccine were distributed for use. Ten million doses of the pandemic vaccine had been produced by mid-January 1969, and nearly 1 million people were immunized before the end of February. About 100,000 doses were designated for the mass immunization of schoolchildren.[72]

In Denmark, the influenza department at the governmental Statens Serum Institut produced about 200,000 doses of pandemic vaccine during the winter of 1968–1969, incorporating a strain isolated in Stockholm. There were no particular difficulties in production, but yield was poor.[73]

Millions of doses of vaccine were available in South Africa before its epidemic began at the end of March 1969, which afforded the opportunity to perform "limited studies" of its effectiveness.[74]

By January 1969, vaccine production in Australia was underway at the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL), then a department of the federal government. The trivalent pandemic vaccine, composed of two influenza A strains and a B strain, was anticipated for release in early March ahead of the winter flu season.[75] The inoculation consisted of a two-dose series, each given four weeks apart.[75]

CSL was aggressive in its promotion of the vaccine, at least to doctors.[76] A spokesman for the laboratories described the new virus as "the worst flu we have had" and called an epidemic that year "almost certain".[77] In light of the situation, the Australian Pensioners Federation in early January wrote to Minister for Health Jim Forbes "demanding" that the vaccine be given free of charge to pensioners.[78] In contrast to CSL's bolder predictions, Forbes described an outbreak that winter as "possible" but did not think it would "necessarily be serious or extensive".[79] While the Department of Health reviewed the question of pandemic vaccine allocation in Australia, the government exported 1 million doses of its vaccine to Britain, already at the peak of its epidemic.[80]

In early February, the epidemiology committee of Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council met in Melbourne to discuss the influenza threat and the best use of vaccine the coming winter.[79][81] A "serious epidemic" was considered the "strongest possibility", and it was recommended to Forbes that older people, children, and pregnant women receive free immunization against the flu.[82] However, the council advised against a mass vaccination campaign, citing the findings of its study which showed the unreliable protection against infection of the present vaccines, and considered it unwise to vaccinate healthy people while the limited supply could be better used to mitigate severe outcomes in at-risk groups.[83]

On the last day of February, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee met to consider the question of making the pandemic vaccine a pharmaceutical benefit for pensioners.[83] Before the end of the week, Forbes announced that shots would be given for free to all pensioners and their dependents, representing about two-thirds of the three groups recommended for priority immunization. The policy would go into effect starting 1 April.[84]

Vaccination against the flu was recommended beginning 1 March,[85] but issues surrounding availability of vaccine soon became apparent throughout the month.[86] In response to Representative Gordon Scholes of Victoria, who had heard complaints from chemists unable to acquire vaccine, Forbes clarified that bulk orders from larger establishments would be met first. He relayed the expectation of the director of CSL that the present situation would be met once quantities of single doses became available in early April.[85]

In the middle of March, Forbes assured that all medical practitioners would be able to acquire the vaccine by the middle of April. He described the new type of flu as milder than that which Australia had typically seen each year.[87]

Representative Charles Jones of Newcastle later in the month questioned Forbes why his home city's order had not been filled. Forbes revealed the export of 1 million doses to Britain earlier in the year but assured that the order "did not delay, or in any way hinder, [the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories'] capacity to fill Australian orders" and that there would be enough supply to meet expected demand.[80] By this time, 1,755,000 doses had been released, and production continued its pace of 200,000 doses per week.[88]

Despite these assurances from Forbes, the Director General of the Department of Health William Refshauge sent a letter on 9 April to all doctors in the country asking them not to vaccinate healthy people until at-risk groups in the community have been inoculated. Forbes reported meeting with the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories commission to discuss how to speed up distribution of vaccine.[89] Two days later, the director of CSL, W. R. Lane, dismissed criticism of the supply situation from the New South Wales branch of the Australian Medical Association as "a lot of nonsense". Contradicting the laboratories' more forceful marketing earlier in the year, he downplayed the likelihood of a serious epidemic but shared the expectation of 4 million doses distributed by the end of May, eight times as much as the average annual total distribution of 500,000 vaccine doses.[90]

On 22 April, Forbes testified in the House of Representatives regarding the vaccine situation. He reported 2.5 million doses had been produced by this time since February. When asked by Representative Theo Nicholls of South Australia to consider importing vaccine to alleviate the present shortage, Forbes noted that the country had already imported the 150,000 doses available. He lamented CSL's recent subjection to a "good deal of abuse" regarding the "temporary shortages" around the country, repeating the comparison between the present production effort and the country's average annual distribution of only 500,000 doses.[91] That same day, N. F. Keith, president of the Victorian branch of the Pharmacy Guild, called on CSL to explain the situation surrounding vaccine supply to the public, which was putting pressure on chemists due to the lack of vaccines.[92]

On 25 April, it was reported that the Department of Health had reimported the remaining vaccine from the order of 1 million that the government had exported to Britain in January. After being sent to Britain, packaged there, and then sent back to Australia, it was sold to doctors at a markup of nearly 50 percent. Doctors criticized the Department and CSL's poor planning with respect to vaccine supply and the decision to export vaccine to Britain when it had already reached the peak of its flu season. They also blamed the shortage on an overreaction by the public, a response which they considered largely due to public statements made by CSL and health officials.[76] The Department later attributed the decision to reimport the vaccine to a desire to ensure a reliable supply for pensioners.[93] It also denied any involvement in the commercial sales of vaccine, in response to reporting on price markups on the reimported vaccine,[94] saying that all it did was authorize the reimportation and list the product as a pharmaceutical benefit.[95] The government itself was paying the same for the reimported vaccine as it was for that being distributed by CSL.[94]

By the end of April, 2.8 million doses of vaccine had been produced and distributed, with no signs of production slowing down. 250,000 doses were now being produced each week, and nearly half a million more were anticipated for 2 May.[95]

Aftermath

The H3N2 virus displaced the previously circulating H2N2 virus, which first emerged in 1957, and returned during the following 1969–70 flu season, which resulted in a second, deadlier wave of deaths in Europe, Japan, and Australia.[33]

Following the season of intense activity in many countries in the Southern Hemisphere, there was relatively low incidence of flu the subsequent two global flu seasons, from October 1970 to September 1971. Influenza B was predominant in the north, causing extensive outbreaks in the United States, but minimal in the south. The Hong Kong virus, on the other hand, was responsible for some large outbreaks in the Southern Hemisphere, some most likely occurring in populations that had still not been exposed to the virus.[96]

It was during this period that the city of Coonoor, in India, experienced a "fairly extensive" outbreak, in July 1971. Samples of the virus responsible were collected but their significance was not immediately recognized. The virus did not immediately spread to other countries, or at least did not immediately cause outbreaks, but it was amid an epidemic in England in early 1972, fueled by more original strains, that a variant showing considerable antigenic drift was identified in one isolate tested out of over 700. It ultimately came to be designated A/England/42/72. It was soon recognized, by comparison with the strains isolated then, that this virus had been the one responsible for the epidemic in India.[97]

The novel variant did not immediately spread after that outbreak, and circulating strains largely continued to resemble quite closely the original Hong Kong virus through April 1972.[98] In May, however, at the onset of the flu season in the Southern Hemisphere, epidemics caused by the variant struck Malaysia, Singapore, and Australia, though South Africa and South America were unaffected.[99] The die seemingly cast, the novel variant went on to cause widespread outbreaks in the Northern Hemisphere, by which point US press had dubbed the bug "London flu". It completely replaced the previous strains still resembling the original pandemic virus.[97] In places such as the US and England and Wales, the 1972–1973 flu season was the deadliest since their respective deadliest waves of the pandemic between 1968 and 1970.[100][97]

Influenza A/H3N2 remains in circulation today as a strain of seasonal flu.[2]

Clinical data

Flu symptoms typically lasted four to five days, but some cases persisted for up to two weeks.[30]

Virology

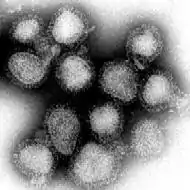

The Hong Kong flu was the first known outbreak of the H3N2 strain, but there is serologic evidence of H3N1 infections in the late 19th century. The virus was isolated in Queen Mary Hospital.[101]

Soon after the initial outbreak in Hong Kong, the virus responsible was recognized to be antigenically distinct from the current influenza A strain in circulation (which at the time was called "A2") but was generally not considered an entirely new subtype.[102] Analysis using the conventional techniques at the time revealed that it was indeed very different from older A2 viruses but also, at the same time, seemingly related to them, depending on one's reading of the data. Experiments involving newer methods of analysis soon identified another surface antigen, neuraminidase, in addition to hemagglutinin, which had already been recognized. It thus became clear that it was the hemagglutinin that had changed compared to older strains while the neuraminidase was identical.[103] These findings, in part, prompted the World Health Organization in 1971 to revise its system of nomenclature for influenza viruses, taking into consideration both antigens. The novel virus was thereafter designated H3N2, indicating its partial similarity to H2N2 but also its antigenic distinction.[104]

The H3N2 pandemic flu strain contained genes from a low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus.[8] Specifically, it had acquired a new hemagglutinin gene and a new PB1 gene, while it preserved the neuraminidase and five other genes from the preexisting human H2N2 strain. The new hemagglutinin helped H3N2 evade preexisting immunity in humans. It is possible that the new PB1 facilitated viral replication and human-to-human transmission.[105]

The new subtype arose in pigs coinfected with avian and human viruses and was soon transferred to humans. Swine were considered the original "intermediate host" for influenza because they supported reassortment of divergent subtypes. However, other hosts appear capable of similar coinfection (such as many poultry species), and direct transmission of avian viruses to humans is possible. H1N1, associated with the 1918 flu pandemic, may have been transmitted directly from birds to humans.[106]

Accumulated antibodies to the neuraminidase or internal proteins may have resulted in many fewer casualties than most other pandemics. However, cross-immunity within and between subtypes of influenza is poorly understood.

The basic reproduction number of the flu in this period was estimated at 1.80.[107]

Mortality

The estimates of the total death toll due to Hong Kong flu (from its beginning in July 1968 until the outbreak faded during the winter of 1969–70[108]) vary:

- The World Health Organization and Encyclopaedia Britannica estimated the number of deaths due to Hong Kong flu to be between 1 and 4 million globally.[1][34]

- The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that, in total, the virus caused the deaths of 1 million people worldwide.[109]

However, the death rate from the Hong Kong flu was lower than most other 20th-century pandemics.[30] The World Health Organization estimated the case fatality rate of Hong Kong flu to be lower than 0.2%.[1] The disease was allowed to spread through the population without restrictions on economic activity, and a vaccine created by American microbiologist Maurice Hilleman and his team became available four months after it had started.[45][65][64] Fewer people died during this pandemic than in previous pandemics for several reasons:[109]

- Some immunity against the N2 flu virus may have been retained in populations struck by the Asian Flu strains that had been circulating since 1957.

- The pandemic did not gain momentum until near the winter school holidays in the Northern Hemisphere, thus limiting the infection's spread.

- Improved medical care gave vital support to the very ill.

- The availability of antibiotics that were more effective against secondary bacterial infections.

By region

For this pandemic, there were two geographically distinct mortality patterns. In North America (the United States and Canada), the first pandemic season (1968–69) was more severe than the second (1969–70). In the "smoldering" pattern seen in Europe and Asia (United Kingdom, France, Japan, and Australia), the second pandemic season was two to five times more severe than the first.[33] The United States health authorities estimated that about 34,000[110][111] to 100,000[109] people died in the US; most excess deaths were in those aged 65 and older.[112]

References

- "Pandemic Influenza Risk Management: WHO Interim Guidance" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2013. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021.

- Rogers, Kara (25 February 2010). "1986 flu pandemic". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Open Publishing. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Paul, William E. (2008). Fundamental Immunology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1273. ISBN 9780781765190. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- "World health group issues alert Mexican president tries to isolate those with swine flu". Associated Press. 25 April 2009. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Mandel, Michael (26 April 2009). "No need to panic... yet Ontario officials are worried swine flu could be pandemic, killing thousands". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- "History's deadliest pandemics, from ancient Rome to modern America". Washington Post. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "1968 Pandemic (H3N2 virus)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Jester, Barbara J.; Uyeki, Timothy M.; Jernigan, Daniel B. (May 2020). "Fifty Years of Influenza A(H3N2) Following the Pandemic of 1968". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (5): 669–676. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305557. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 7144439. PMID 32267748.

- "How 1968's deadly Hong Kong flu left more than one million dead". South China Morning Post. 13 July 2018. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Chang, W. K. (1969). "National Influenza Experience in Hong Kong, 1968" (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization. WHO. 41 (3): 349–351. PMC 2427693. PMID 5309438. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Hong Kong Flu (1968 Influenza Pandemic)". Sino Biological. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Peckham, Robert (6 November 2020). "Viral surveillance and the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemic". Journal of Global History. 15 (3): 444–458. doi:10.1017/S1740022820000224. S2CID 228943153 – via Cambridge University Press.

- Cockburn, W. Charles (1969). "Origin and progress of the 1968-69 Hong Kong influenza epidemic". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3–4–5): 343–348. PMC 2427756. PMID 5309437.

- "The 'Hong Kong Flu' Began in Red China". The New York Times. 15 December 1968. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Qin, Ying; et al. (2018). "History of influenza pandemics in China during the past century". Chinese Journal of Epidemiology (in Chinese). 39 (8): 1028–1031. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.003. PMID 30180422. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1968, vol. 43, 33". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43: 411. 16 August 1968. hdl:10665/216745 – via IRIS.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1968, vol. 43, 35". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43: 448. 30 August 1968. hdl:10665/216769.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1968, vol. 43, 37". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43: 467. 13 September 1968. hdl:10665/216790 – via IRIS.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1968, vol. 43, 38". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43: 473–484. 20 September 1968. hdl:10665/216802 – via IRIS.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1968, vol. 43, 41". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43: 523. 11 October 1968. hdl:10665/216842 – via IRIS.

- Roden, A. T. (1969). "National experience with Hong Kong influenza in the United Kingdom, 1968-69". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 375–380. hdl:10665/262513. PMC 2427738. PMID 5309441.

- Veeraraghavan, N. (1969). "Hong Kong influenza in Madras State, India, 1968". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 399–400. hdl:10665/262500. PMC 2427725. PMID 5309446.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1968, vol. 43, 40". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43: 501–512. 4 October 1968. hdl:10665/216823 – via IRIS.

- "Weekly Epidemiological Record, 1968, vol. 43, 42". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 43: 529–540. 18 October 1968. hdl:10665/216852 – via IRIS.

- "Eighth International Congresses on Tropical Medicine and Malaria, Teheran, Iran (7–15 September, 1968)". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 63: 144–145. 1 January 1969. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(69)90101-1 – via Oxford University Press.

- Saenz, A. C. (11 January 1969). "Outbreak of A2/Hong Kong/68 Influenza at an International Medical Conference". The Lancet. 293 (7585): 91–93. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(69)91104-0. PMID 4178014 – via ScienceDirect.

- Williams, W. O. (June 1971). "H.K. influenza 1969-70. A practice study". The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 21 (107): 325–335. PMC 2156343. PMID 5581832.

- Fukumi, Hideo (1969). "Summary report on Hong Kong influenza in Japan". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 353–359. hdl:10665/262490. PMC 2427713. PMID 5309439.

- Ždanov, V. M. (1969). "The Hong Kong influenza virus epidemic in the USSR*". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 381–386. hdl:10665/262485. PMC 2427708. PMID 5309442.

- Starling, Arthur (2006). Plague, SARS, and the Story of Medicine in Hong Kong. HK University Press. p. 55. ISBN 962-209-805-3. Archived from the original on 18 June 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- "Symposium on the Asian Influenza Epidemic, 1957". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 51 (12): 1009–1018. 1 December 1958. doi:10.1177/003591575805101205. ISSN 0035-9157.

- "Asian Flu Is World-Wide". The New York Times. 12 October 1957. p. 21. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Viboud, Cécile; Grais, Rebecca F.; Lafont, Bernard A. P.; Miller, Mark A.; Simonsen, Lone (15 July 2005). "Multinational Impact of the 1968 Hong Kong Influenza Pandemic: Evidence for a Smoldering Pandemic". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 192 (2): 233–248. doi:10.1086/431150. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 15962218.

- Honigsbaum, Mark (13 June 2020). "Revisiting the 1957 and 1968 influenza pandemics". The Lancet. 395 (10240): 1824–1826. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31201-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7247790. PMID 32464113.

- "200,000 in Rome Have Flu (Published 1968)". The New York Times. 3 November 1968. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "The crises of winters past". BBC. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- "Desert Sun 28 May 1969 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Murray, Roderick (1969). "Production and testing in the USA of influenza virus vaccine made from the Hong Kong variant in 1968-69". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41: 493–496. hdl:10665/262478. Retrieved 20 April 2022 – via IRIS.

- "Influenza". hansard.parliament.uk. 30 January 1969. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Outbreak of Asian Flu Is Expected This Fall". The New York Times. 5 September 1968. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Jones, Robert T. (6 December 1968). "ASIATIC FLU TAKES TOLL AT 'LA BOHEME'". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Jones, F. Avery (1968), "Winter Epidemics", British Medical Journal, 1968 (4): 327, doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5626.327-c, PMC 1912285

- Coleman, Marion T.; Dowdle, Walter R.; Pereira, Helio G.; Schild, Geoffrey C.; Chang, W. K. (1968), "The Hong Kong/68 Influenza A2 Variant", The Lancet, 292 (7583): 1384–1386, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(68)92683-4, PMID 4177941

- "Si u prek Shqipëria nga gripi spanjoll në 1918 dhe ai kinez në 1970! Dokumentet e panjohura|DOSJA E". YouTube.

- Pancevski, Bojan (24 April 2020). "Forgotten Pandemic Offers Contrast to Today's Coronavirus Lockdowns". The Wall Street Journal.

- "Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 17, no. 26 Week ending June 29, 1968". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 17: 246–247. 29 June 1968 – via CDC.

- "Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 17, no. 35 Week ending August 31, 1968". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 17: 247. 31 August 1968 – via CDC.

- "Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 17, no. 36 Week ending September 7, 1968". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 17. 7 September 1968 – via CDC.

- Sharrar, Robert G. (1969). "National influenza experience in the USA, 1968-69". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 361–366. hdl:10665/262499?search-result=true&query=National%20Influenza%20Experience%20in%20the%20USA,%201968-69&scope=&rpp=10&sort_by=score&order=desc. PMC 2427724. PMID 5309440.

- "HONG KONG FLU NOW U.S. EPIDEMIC". The New York Times. 13 December 1968. p. 16. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Ronan, Thomas P. (14 December 1968). "FLU IMPACT GROWS ACROSS THE NATION". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Influenza-respiratory disease surveillance report no. 85, June 30, 1969". Influenza Surveillance Reports: 1. 30 June 1969.

- Koshetz, Herbert (22 December 1968). "Hong Kong Flu the Chief Culprit as Holiday Sales Lose Impetus". The New York Times. p. 13. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Gwertzman, Bernard (19 December 1968). "Johnson in Hospital With Cold and Fever". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Johnson, Recuperating, Returns to White House". The New York Times. 23 December 1968. p. 31. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Welles, Benjamin (20 December 1968). "JOHNSON BETTER, BUT FLU LINGERS". The New York Times. p. 57. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "A Touch of Flu Dogs Nixon at the Wedding". The New York Times. 23 December 1968. p. 53. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Gal, Harold (24 December 1968). "NIXON IN FLORIDA FOR THE HOLIDAY". The New York Times. p. 8. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Immunization against infectious disease 1968". Stephen B. Thacker CDC Library Collection. 1968 – via CDC.

- "Morbidity and mortality weekly report, Vol. 18, no. 25, June 21, 1969". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 18. 27 June 1969 – via CDC.

- "Influenza-respiratory disease surveillance report no. 86, December 1970". Influenza Surveillance Reports. December 1970 – via CDC.

- World Health Organization; Candau, Marcolino Gomes (April 1969). "The work of WHO, 1968: annual report of the Director-General to the World Health Assembly and to the United Nations". Official Records of the World Health Organization. hdl:10665/85812. ISBN 9789241601726 – via IRIS.

- Schmeck Jr., Harold M. (9 February 1969). "Hong Kong Flu: Story of the Close Race Between Man and the Virus". The New York Times. p. 75. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). "Maurice Hilleman: Creator of Vaccines That Changed the World". Case Studies in Public Health: 443–470. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00003-2. ISBN 9780128045718. PMC 7150172.

- "Vaccine for Hong Kong Influenza Pandemic". History of Vaccines. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Influenza Vaccine". The New York Times. 7 July 1957. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Vaccine Ready Soon For Hong Kong Flu". The New York Times. 19 November 1968. p. 93. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "APOLLO 8 CREW GETS INJECTIONS FOR FLU". The New York Times. 4 December 1968. p. 95. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Hilleman, Maurice R. (1969). "The roles of early alert and of adjuvant in the control of Hong Kong influenza by vaccines". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 623–628. hdl:10665/262476. PMC 2427699. PMID 4985377.

- Langmuir, Alexander D.; Housworth, Jere (1969). "A critical evaluation of influenza surveillance". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 393–398. hdl:10665/262524. PMC 2427749. PMID 5309444.

- Fukumi, Hideo (1969). "Vaccination against Hong Kong influenza in Japan". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 555. hdl:10665/262529. PMC 2427754. PMID 5309473.

- Ikić, D. (1969). "Experience in Yugoslavia with live influenza vaccine prepared from an attenuated A2/Hong Kong/68 strain". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 608–609. hdl:10665/262515. PMC 2427740. PMID 5309485.

- von Magnus, Preben (1969). "Experience with the production of Hong Kong influenza vaccine at the Statens Seruminstitut, Copenhagen". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3): 556–557. hdl:10665/262505. PMC 2427730. PMID 5309474.

- "General discussion—Session I". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 41 (3–5): 407–411. 1969. hdl:10665/262520. PMC 2427745. PMID 20604350.

- "Vaccine ready in March". The Canberra Times. 24 January 1969. p. 11. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Gaul, Jonathan (25 April 1969). "CSL flu vaccine reimported at higher price". The Canberra Times. p. 1. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Vaccine for PS to prevent Hong Kong influenza". The Canberra Times. 8 January 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Flu vaccine may be free". The Canberra Times. 11 January 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Experts to advise on flu threat". The Canberra Times. 16 January 1969. p. 15. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Assurance on flu vaccine". The Canberra Times. 28 March 1969. p. 15. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Free flu vaccine for aged wanted". The Canberra Times. 7 February 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Free influenza immunisation proprosed". 12 February 1969. p. 8. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Govt unlikely to give mass flu 'shots'". The Canberra Times. 13 February 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Vaccine a benefit, free to pensioners". The Canberra Times. 3 March 1969. p. 1. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Bulk supplies of vaccine first". The Canberra Times. 5 March 1969. p. 11. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Canberra patients wait for vaccine". The Canberra Times. 18 March 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "New flu strain not severe". The Canberra Times. 19 March 1969. p. 11. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- "Big demand for anti-flu vaccine". The Canberra Times. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Appeal to doctors on Hong Kong flu injections". The Canberra Times. 9 February 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Undue urgency over vaccine, CSL head says". 11 April 1969. p. 11. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Flu vaccine available by May". The Canberra Times. 23 April 1969. p. 17. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "CSL asked to explain on vaccine". The Canberra Times. 22 April 1969. p. 11. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Vaccine reimported to meet need". The Canberra Times. 29 April 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Denial on vaccine". The Canberra Times. 28 April 1969. p. 3. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- "CSL will maintain vaccine rate". The Canberra Times. 30 April 1969. p. 20. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- World Health Organization (1971). "INFLUENZA IN THE WORLD: PERIOD OCTOBER 1970 — SEPTEMBER 1971". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 50: 505. hdl:10665/218625 – via IRIS.

- Cockburn, W. C. (2 June 1973). "Influenza — The World Problem". Medical Journal of Australia. 1 (SP1): 8. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1973.tb111167.x. PMID 4717620.

- World Health Organization (1972). "INFLUENZA IN THE WORLD: OCTOBER 1971 - SEPTEMBER 1972*". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 47: 430. hdl:10665/219147 – via IRIS.

- World Health Organization (1972). "ANTIGENIC VARIATION IN INFLUENZA A VIRUSES". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 47: 381. hdl:10665/219102 – via IRIS.

- Center for Disease Control (February 1974). "Influenza-respiratory disease surveillance report no. 89, 1972-1973". Influenza Surveillance Report: 6 – via CDC.

- Peckham, Robert (November 2020). "Viral surveillance and the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemic". Journal of Global History. 15 (3): 444–458. doi:10.1017/S1740022820000224. ISSN 1740-0228.

- Wiebenga, N. H. (September 1970). "Epidemic disease in Hong Kong, 1968, associated with an antigenic variant of Asian influenza virus". American Journal of Public Health and the Nation's Health. 60 (9): 1806–1812. doi:10.2105/ajph.60.9.1806. PMC 1349075. PMID 5466726.

- Kilbourne, Edwin D. (1 April 1973). "The Molecular Epidemiology of Influenza". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 127 (4): 478–487. doi:10.1093/infdis/127.4.478. PMID 4121053 – via DeepDyve.

- "A revised system of nomenclature for influenza viruses*". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 45 (1): 119–124. 1971. hdl:10665/262638. PMC 2427881. PMID 5316848.

- Wendel, Isabel (19 March 2015). "The Avian-Origin PB1 Gene Segment Facilitated Replication and Transmissibility of the H3N2/1968 Pandemic Influenza Virus". Journal of Virology. 89 (8): 4170–4179. doi:10.1128/JVI.03194-14. PMC 4442368. PMID 25631088.

- Belshe, R. B. (2005). "The origins of pandemic influenza – lessons from the 1918 virus". New England Journal of Medicine. 353 (21): 2209–2211. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058281. PMID 16306515. Cited in Harder, Timm C.; Werner, Ortrud. Kamps, Bernd Sebastain; Hoffmann, Christian; Preiser, Wolfgang (eds.). "Influenza Report". Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- Biggerstaff, M.; Cauchemez, S.; Reed, C.; et al. (2014). "Estimates of the reproduction number for seasonal, pandemic, and zoonotic influenza: a systematic review of the literature". BMC Infectious Diseases. 14 (480): 480. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-480. PMC 4169819. PMID 25186370.

- Dutton, Gail (13 April 2020). "The 1968 Pandemic Strain (H3N2) Persists. Will COVID-19?". BioSpace. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "1968 Pandemic (H3N2 virus)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- "Pandemics and Pandemic Threats since 1900". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 31 March 2009.

- "Details - Public Health Image Library(PHIL)". phil.cdc.gov.

- Shiel, William. "Medical Definition of Hong Kong flu". MedicineNet. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

External links

- Influenza Research Database – Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.