Royal Exhibition Building

The Royal Exhibition Building is a World Heritage-listed building in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, built in 1879–1880 as part of the international exhibition movement, which presented over 50 exhibitions between 1851 and 1915 around the globe. The building sits on approximately 26 hectares (64 acres), is 150 metres (490 ft) long and is surrounded by four city streets.[1] It is at 9 Nicholson Street in the Carlton Gardens, flanked by Victoria, Carlton and Rathdowne Streets, at the north-eastern edge of the central business district. It was built to host the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880–81, and then hosted the even larger Centennial International Exhibition in 1888, and the formal opening of the first Parliament of Australia in 1901. The building is representative of the money and pride Victoria had in the 1870s.[2] Throughout the 20th century smaller sections and wings of the building were subject to demolition and fire; however, the main building, known as the Great Hall, survived.

| Royal Exhibition Building | |

|---|---|

The Royal Exhibition Building, with its fountain on the southern or Carlton Gardens side. | |

| General information | |

| Location | 9 Nicholson Street, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Coordinates | 37°48′17″S 144°58′17″E |

| Construction started | 1879 |

| Completed | 1880 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Joseph Reed |

| Official name | Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii |

| Designated | 2004 (28th session) |

| Reference no. | 1131 |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

It received restoration throughout the 1990s and in 2004 became the first building in Australia to be awarded UNESCO World Heritage status, being one of the last remaining major 19th-century exhibition buildings in the world. It is the world's most complete surviving site from the International Exhibition movement 1851–1914. It sits adjacent to the Melbourne Museum and is the largest item in Museum Victoria's collection. Today, the building hosts various exhibitions and other events and is closely tied with events at the Melbourne Museum.

History

The Royal Exhibition Building was designed by the architect Joseph Reed of Reed and Barnes architecture, who also designed the Melbourne Town Hall, the State Library of Victoria, and the Baroque style gardens. The Royal Exhibition Building was the largest design completed by Reed and Barnes.[2] According to Reed, the eclectic design was inspired by many sources. Composed of brick, timber, steel, and slate, the Exhibition Building is representative of the Byzantine, Romanesque, Lombardic and Italian Renaissance styles.[3] The dome was modeled on the Florence Cathedral, while the main pavilions were influenced by the style of Rundbogenstil and several buildings from Normandy, Caen and Paris.[4] The building has the scale of the French Beaux Arts, with a cruciform plan in the shape of a Latin cross, with long nave-like wings symmetrically placed east–west about the central dome, and a shorter wing to the north.[1] The Great Hall is still in beautiful condition, crowned by an octagonal drum and dome rising 68 metres, and 18.3 metres across. The dome was formed using cast iron and timber frame and has a double shell. At the crossing, windows in the drum of the dome bring in sunlight for a bright open space. The interior is painted in the colour scheme of 1901, with murals and the words "Victoria Welcomes All Nations" under the dome surviving from 1888.[5] In 1888, electric lighting was installed for the Centennial International Exhibition, making it one of the first in the world that was accessible during night time. The interior decorations changed between the two exhibitions of 1880 and 1888. In 1880, the walls were left bare and windows and door joinery colored green. In 1888, walls were painted for the first time. The decoration was by interior designer John Ross Anderson.[6]

It was built by David Mitchell, who also built Scots' Church and St Patrick's Cathedral. He was also the father of the famed soprano Dame Nellie Melba, who sang at the opening of the Provisional Parliament House in Canberra in 1927. Mitchell was a member of the Council of the Royal Agricultural society and also the Builders and Contractor's association.[7]

The foundation stone was laid by Victorian governor George Bowen on 19 February 1879[8] and it was completed in just 18 months, opening on October 1, 1880, as the Melbourne International Exhibition. The building consisted of a Great Hall of over 12,000 square metres, flanking lower annexes to the north on the east and west sides, and many temporary galleries between.

1880–1901

In the 1880s, the building hosted two major International Exhibitions: The Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880 and the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition in 1888, celebrating a century of European settlement in Australia. The most significant event to occur in the Exhibition Building was the opening of the first Parliament of Australia on 9 May 1901, following the inauguration of the Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January. After the official opening, the Federal Parliament moved to the Victorian State Parliament House, while the Victorian Parliament moved to the Exhibition Building for the next 26 years.

On 3 September 1901, the Countess of Hopetoun, wife of the Governor-General, announced the winners of a competition to design the Australian National Flag. A large flag, 5.5 metres by 11 metres, was unfurled and flown over the dome of the Royal Exhibition Building.[9]

1901–1979

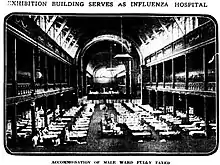

In 1902, the building hosted the Australian Federal International Exhibition.[10] The period after this time saw the building used for many purposes. During the 1919 Spanish flu epidemic, the building was used as an influenza hospital.[11]

As it decayed, it became known derogatively by locals as The White Elephant in the 1940s[12] and by the 1950s, like many buildings in Melbourne of that time it was earmarked for replacement by office blocks.[13] In 1948, members of the Melbourne City Council put this to the vote and it was narrowly decided not to demolish the building.[14] The wing of the building which once housed Melbourne Aquarium burnt down in 1953. It was a venue for the 1956 Summer Olympics, hosting the basketball, weightlifting, wrestling, and the fencing part of the modern pentathlon competitions.[15][16] During the 1940s and 1950s, the building remained a venue for regular weekly dances. Over some decades of this period it also held boat shows, car shows and other regular home and building industry shows. It was also used during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s for State High School Matriculation and for the Victorian Certificate of Education examinations, among its various other purposes. The western annexe was demolished in the 1970s.[17] The last remaining original annex, the grand ballroom, was demolished amid controversy in 1979.[18] It was replaced with a new building on the same footprint providing more exhibition space, clad in mirror glass, in 1980. On 1 October 1980 during a visit to Victoria, Princess Alexandra unveiled a plaque which commemorated both the opening of the new mirror-glass "Centennial Hall", and the centenary of the building. She also unveiled a second plaque commemorating the bestowal of the title "Royal" on the building by Her Majesty the Queen.

1980–present

Following the outcry over the ballroom demolition, and the appointment of new Trustees and a new Chair in 1983, the heritage of the building began to be seen as important as providing modern space for exhibitions.

The first conservation assessment of the building was undertaken by Alan Willingham in 1987, and over the following decades the Great hall was progressively renovated and restored.[19] In 1996, the then Premier of Victoria, Jeff Kennett, proposed the location and construction of Melbourne's State Museum in the carpark to the north, which involved the demolition of the 1960s annexes in 1997–98.

The biennial Melbourne Art Fair took place at the Royal Exhibition Building from 1988 to 2014.[20][21]

The location of the Melbourne Museum close to the Exhibition Building site was strongly opposed by the Victorian State Labor Party, the Melbourne City Council and some in the local community. Due to the community campaign opposing the museum development, John Brumby, then State opposition leader, with the support of the Melbourne City Council, proposed the nomination of the Royal Exhibition Building for world heritage listing. The world heritage nomination did not progress until the election of the Victorian State Labor Party as the new government in 1999.

On 1 July 2004, the Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens was granted listing as a World Heritage Site, the first building in Australia to be granted this status. The heritage listing states that "The Royal Exhibition Building is the only major extant nineteenth-century exhibition building in Australia. It is one of the few major nineteenth-century exhibition buildings to survive worldwide."

In October 2009, Museum Victoria embarked upon a major project to restore the former German Garden of the Western Forecourt. The area had been covered by asphalt in the 1950s for car parking.[22]

Renovations

Renovations include the timber flooring, building services, externals, and stonework. Most timber staircases have been replaced by concrete for safety also, though the site has continued to be very authentic through all renovations. All additions have been removed such as the East and West annexes and the two North structures.[3] The Australian Government has recently granted $20 million for further renovation to protect and promote the Royal Exhibition Building. The South facade will undergo conservation works, the dome of the Great Hall will be repaired and be part of a new experience. The basement will be turned into a curatorial exhibition experience. This will be a place where history is brought to life, and ideas of the future are expanded upon. The Australian Department of Environment and Energy, along with Heritage Victoria, Creative Victoria and Museums Victoria will oversee the projects. The renovations are predicted to be finished by 2020.[23]

Current use

The Royal Exhibition Building is used to this day as an exhibition venue for various festivals and fairs such as Melbourne Fashion Week. During the recent Covid-19 pandemic, the building was used as a mass vaccination centre, operated by St Vincent's Hospital.[24]

The Royal Exhibition Building is used as an exam hall for the University of Melbourne, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, Melbourne High School, Nossal High School, Mac.Robertson Girls' High School and Suzanne Cory High School.

The building is no longer Melbourne's largest commercial exhibition centre. The modern alternative is the Melbourne Convention & Exhibition Centre, which is in Southbank to the south of the Melbourne central business district.

References

- "Royal Exhibition building and Carlton Gardens" (PDF). Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens, World Heritage Management Plan" (PDF). October 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2004. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- Willis, Elizabeth (2004). The Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne. A Guide. Melbourne, Victoria: Museum Victoria. p. 2. ISBN 0-9577471-4-4.

- "The Royal Exhibition Building of "Marvellous Melbourne"". TheGuardian.com. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- "The Building". Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- Campbell, Joan. Mitchell, David (1829–1916). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- The Age Archived 21 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- It's an Honour Archived 19 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION". The Argus (Melbourne: 1848–1957). Melbourne: National Library of Australia. 1 November 1902. p. 17. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Melbourne at War – Stop 7". Heritage Council of Victoria. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- "The Royal Exhibition Building Archived 4 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine" museumvictoria.com.au. URL accessed on 6 November 2007.

- "Who will save Melbourne from the wrecker's ball? Archived 3 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine" theage.com.au 15 March 2004. URL accessed on 5 September 2006.

- Wills, Elizabeth (2004). The Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne. A Guide. Melbourne, Victoria: Museum Victoria. pp. Foreword. ISBN 0-9577471-4-4.

- "The Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- 1956 Summer Olympics official report. Archived 12 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. p. 43.

- "The Building: Royal Exhibition Building". museumsvictoria.com.au.

- "Museum Victoria" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "Global status for our greatest building" Archived 12 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 21 October 2002. URL accessed on 5 September 2006.

- "Review: Melbourne Art Fair Viewing Rooms". ArtsHub Australia. 9 June 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- Francis, Hannah (9 July 2019). "Melbourne art fair returns with design flair". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- "World Heritage, World Futures" museumvictoria.com.au. URL accessed on 12 March 2010.

- "Major Project". Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- Richards, Tim (11 June 2021). "'It's stunning': Australia's UNESCO World Heritage-listed vaccine hub". Traveller. Retrieved 2 November 2021.