Register allocation

In compiler optimization, register allocation is the process of assigning local automatic variables and expression results to a limited number of processor registers.

Register allocation can happen over a basic block (local register allocation), over a whole function/procedure (global register allocation), or across function boundaries traversed via call-graph (interprocedural register allocation). When done per function/procedure the calling convention may require insertion of save/restore around each call-site.

Context

Principle

| Architecture | 32 bit | 64 bit |

|---|---|---|

| ARM | 15 | 31 |

| Intel x86 | 8 | 16 |

| MIPS | 32 | 32 |

| POWER/PowerPC | 32 | 32 |

| RISC-V | 16/32 | 32 |

| SPARC | 31 | 31 |

In many programming languages, the programmer may use any number of variables. The computer can quickly read and write registers in the CPU, so the computer program runs faster when more variables can be in the CPU's registers.[1] Also, sometimes code accessing registers is more compact, so the code is smaller, and can be fetched faster if it uses registers rather than memory. However, the number of registers is limited. Therefore, when the compiler is translating code to machine-language, it must decide how to allocate variables to the limited number of registers in the CPU.[2][3]

Not all variables are in use (or "live") at the same time, so, over the lifetime of a program, a given register may be used to hold different variables. However, two variables in use at the same time cannot be assigned to the same register without corrupting one of the variables. If there are not enough registers to hold all the variables, some variables may be moved to and from RAM. This process is called "spilling" the registers.[4] Over the lifetime of a program, a variable can be both spilled and stored in registers: this variable is then considered as "split".[5] Accessing RAM is significantly slower than accessing registers [6] and so a compiled program runs slower. Therefore, an optimizing compiler aims to assign as many variables to registers as possible. A high "Register pressure" is a technical term that means that more spills and reloads are needed; it is defined by Braun et al. as "the number of simultaneously live variables at an instruction".[7]

In addition, some computer designs cache frequently-accessed registers. So, programs can be further optimized by assigning the same register to a source and destination of a move instruction whenever possible. This is especially important if the compiler is using an intermediate representation such as static single-assignment form (SSA). In particular, when SSA is not fully optimized it can artificially generate additional move instructions.

Components of register allocation

Register allocation consists therefore of choosing where to store the variables at runtime, i.e. inside or outside registers. If the variable is to be stored in registers, then the allocator needs to determine in which register(s) this variable will be stored. Eventually, another challenge is to determine the duration for which a variable should stay at the same location.

A register allocator, disregarding the chosen allocation strategy, can rely on a set of core actions to address these challenges. These actions can be gathered in several different categories:[8]

- Move insertion

- This action consists of increasing the number of move instructions between registers, i.e. make a variable live in different registers during its lifetime, instead of one. This occurs in the split live range approach.

- Spilling

- This action consists of storing a variable into memory instead of registers.[9]

- Assignment

- This action consists of assigning a register to a variable.[10]

- Coalescing

- This action consists of limiting the number of moves between registers, thus limiting the total number of instructions. For instance, by identifying a variable live across different methods, and storing it into one register during its whole lifetime.[9]

Many register allocation approaches optimize for one or more specific categories of actions.

Common problems raised in register allocation

Register allocation raises several problems that can be tackled (or avoided) by different register allocation approaches. Three of the most common problems are identified as follows:

- Aliasing

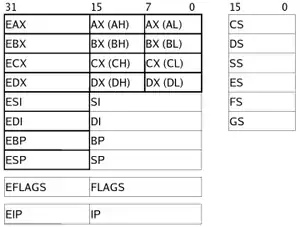

- In some architectures, assigning a value to one register can affect the value of another: this is called aliasing. For example, the x86 architecture has four general purpose 32-bit registers that can also be used as 16-bit or 8-bit registers.[11] In this case, assigning a 32-bit value to the eax register will affect the value of the al register.

- Pre-coloring

- This problem is an act to force some variables to be assigned to particular registers. For example, in PowerPC calling conventions, parameters are commonly passed in R3-R10 and the return value is passed in R3.[12]

- NP-Problem

- Chaitin et al. showed that register allocation is a NP-complete problem. They reduce the graph coloring problem to the register allocation problem by showing that for an arbitrary graph, a program can be constructed such that the register allocation for the program (with registers representing nodes and machine registers representing available colors) would be a coloring for the original graph. As Graph Coloring is an NP-Hard problem and Register Allocation is in NP, this proves the NP-completeness of the problem.[13]

Register allocation techniques

Register allocation can happen over a basic block of code: it is said to be "local", and was first mentioned by Horwitz et al.[14] As basic blocks do not contain branches, the allocation process is thought to be fast, because the management of control-flow graph merge points in register allocation reveals itself a time-consuming operation.[15] However, this approach is thought not to produce as optimized code as the "global" approach, which operates over the whole compilation unit (a method or procedure for instance).[16]

Graph-coloring allocation

Graph-coloring allocation is the predominant approach to solve register allocation.[17][18] It was first proposed by Chaitin et al.[4] In this approach, nodes in the graph represent live ranges (variables, temporaries, virtual/symbolic registers) that are candidates for register allocation. Edges connect live ranges that interfere, i.e., live ranges that are simultaneously live at at least one program point. Register allocation then reduces to the graph coloring problem in which colors (registers) are assigned to the nodes such that two nodes connected by an edge do not receive the same color.[19]

Using liveness analysis, an interference graph can be built. The interference graph, which is an undirected graph where the nodes are the program's variables, is used to model which variables cannot be allocated to the same register.[20]

Principle

The main phases in a Chaitin-style graph-coloring register allocator are:[18]

- Renumber: discover live range information in the source program.

- Build: build the interference graph.

- Coalesce: merge the live ranges of non-interfering variables related by copy instructions.

- Spill cost: compute the spill cost of each variable. This assesses the impact of mapping a variable to memory on the speed of the final program.

- Simplify: construct an ordering of the nodes in the inferences graph

- Spill Code: insert spill instructions, i.e. loads and stores to commute values between registers and memory.

- Select: assign a register to each variable.

Drawbacks and further improvements

The graph-coloring allocation has three major drawbacks. First, it relies on graph-coloring, which is an NP-complete problem, to decide which variables are spilled. Finding a minimal coloring graph is indeed an NP-complete problem.[21] Second, unless live-range splitting is used, evicted variables are spilled everywhere: store (respectively load) instructions are inserted as early (respectively late) as possible, i.e., just after (respectively before) variable definitions (respectively uses). Third, a variable that is not spilled is kept in the same register throughout its whole lifetime.[22]

On the other hand, a single register name may appear in multiple register classes, where a class is a set of register names that are interchangeable in a particular role. Then, multiple register names may be aliases for a single hardware register.[23] Finally, graph coloring is an aggressive technique for allocating registers, but is computationally expensive due to its use of the interference graph, which can have a worst-case size that is quadratic in the number of live ranges.[24] The traditional formulation of graph-coloring register allocation implicitly assumes a single bank of non-overlapping general-purpose registers and does not handle irregular architectural features like overlapping registers pairs, special purpose registers and multiple register banks.[25]

One later improvement of Chaitin-style graph-coloring approach was found by Briggs et al.: it is called conservative coalescing. This improvement adds a criterion to decide when two live ranges can be merged. Mainly, in addition to the non-interfering requirements, two variables can only be coalesced if their merging will not cause further spilling. Briggs et al. introduces a second improvement to Chaitin's works which is biased coloring. Biased coloring tries to assign the same color in the graph-coloring to live range that are copy related.[18]

Linear scan

Linear scan is another global register allocation approach. It was first proposed by Poletto et al. in 1999.[26] In this approach, the code is not turned into a graph. Instead, all the variables are linearly scanned to determine their live range, represented as an interval. Once the live ranges of all variables have been figured out, the intervals are traversed chronologically. Although this traversal could help identifying variables whose live ranges interfere, no interference graph is being built and the variables are allocated in a greedy way.[24]

The motivation for this approach is speed; not in terms of execution time of the generated code, but in terms of time spent in code generation. Typically, the standard graph coloring approaches produce quality code, but have a significant overhead,[27][28] the used graph coloring algorithm having a quadratic cost.[29] Owing to this feature, linear scan is the approach currently used in several JIT compilers, like the Hotspot client compiler, V8, Jikes RVM,[5] and the Android Runtime (ART).[30] The Hotspot server compiler uses graph coloring for its superior code.[31]

Pseudocode

This describes the algorithm as first proposed by Poletto et al.,[32] where:

- R is the number of available registers.

- active is the list, sorted in order of increasing end point, of live intervals overlapping the current point and placed in registers.

LinearScanRegisterAllocation

active ← {}

for each live interval i, in order of increasing start point do

ExpireOldIntervals(i)

if length(active) = R then

SpillAtInterval(i)

else

register[i] ← a register removed from pool of free registers

add i to active, sorted by increasing end point

ExpireOldIntervals(i)

for each interval j in active, in order of increasing end point do

if endpoint[j] ≥ startpoint[i] then

return

remove j from active

add register[j] to pool of free registers

SpillAtInterval(i)

spill ← last interval in active

if endpoint[spill] > endpoint[i] then

register[i] ← register[spill]

location[spill] ← new stack location

remove spill from active

add i to active, sorted by increasing end point

else

location[i] ← new stack location

Drawbacks and further improvements

However, the linear scan presents two major drawbacks. First, due to its greedy aspect, it does not take lifetime holes into account, i.e. "ranges where the value of the variable is not needed".[33][34] Besides, a spilled variable will stay spilled for its entire lifetime.

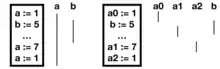

Many other research works followed up on the Poletto's linear scan algorithm. Traub et al., for instance, proposed an algorithm called second-chance binpacking aiming at generating code of better quality.[35][36] In this approach, spilled variables get the opportunity to be stored later in a register by using a different heuristic from the one used in the standard linear scan algorithm. Instead of using live intervals, the algorithm relies on live ranges, meaning that if a range needs to be spilled, it is not necessary to spill all the other ranges corresponding to this variable.

Linear scan allocation was also adapted to take advantage from the SSA form: the properties of this intermediate representation simplify the allocation algorithm and allow lifetime holes to be computed directly.[37] First, the time spent in data-flow graph analysis, aimed at building the lifetime intervals, is reduced, namely because variables are unique.[38] It consequently produces shorter live intervals, because each new assignment corresponds to a new live interval.[39][40] To avoid modeling intervals and liveness holes, Rogers showed a simplification called future-active sets that successfully removed intervals for 80% of instructions.[41]

Rematerialization

Coalescing

In the context of register allocation, coalescing is the act of merging variable-to-variable move operations by allocating those two variables to the same location. The coalescing operation takes place after the interference graph is built. Once two nodes have been coalesced, they must get the same color and be allocated to the same register, once the copy operation becomes unnecessary.[42]

Doing coalescing might have both positive and negative impacts on the colorability of the interference graph.[9] For example, one negative impact that coalescing could have on graph inference colorability is when two nodes are coalesced, as the result node will have a union of the edges of those being coalesced.[9] A positive impact of coalescing on inference graph colorability is, for example, when a node interferes with both nodes being coalesced, the degree of the node is reduced by one which leads to improving the overall colorability of the interference graph.[43]

There are several coalescing heuristics available:[44]

- Aggressive coalescing

- it was first introduced by Chaitin original register allocator. This heuristic aims at coalescing any non-interfering, copy-related nodes.[45] From the perspective of copy elimination, this heuristic has the best results.[46] On the other hand, aggressive coalescing could impact the colorability of the inference graph.[43]

- Conservative Coalescing

- it mainly uses the same heuristic as aggressive coalescing but it merges moves if, and only if, it does not compromise the colorability of the interference graph.[47]

- Iterated coalescing

- it removes one particular move at the time, while keeping the colorability of the graph.[48]

- Optimistic coalescing

- it is based on aggressive coalescing, but if the inference graph colorability is compromised, then it gives up as few moves as possible.[49]

Hybrid allocation

Some other register allocation approaches do not limit to one technique to optimize register's use. Cavazos et al., for instance, proposed a solution where it is possible to use both the linear scan and the graph coloring algorithms.[50] In this approach, the choice between one or the other solution is determined dynamically: first, a machine learning algorithm is used "offline", that is to say not at runtime, to build a heuristic function that determines which allocation algorithm needs to be used. The heuristic function is then used at runtime; in light of the code behavior, the allocator can then choose between one of the two available algorithms.[51]

Trace register allocation is a recent approach developed by Eisl et al.[3][5] This technique handles the allocation locally: it relies on dynamic profiling data to determine which branches will be the most frequently used in a given control flow graph. It then infers a set of "traces" (i.e. code segments) in which the merge point is ignored in favor of the most used branch. Each trace is then independently processed by the allocator. This approach can be considered as hybrid because it is possible to use different register allocation algorithms between the different traces.[52]

Split allocation

Split allocation is another register allocation technique that combines different approaches, usually considered as opposite. For instance, the hybrid allocation technique can be considered as split because the first heuristic building stage is performed offline, and the heuristic use is performed online.[24] In the same fashion, B. Diouf et al. proposed an allocation technique relying both on offline and online behaviors, namely static and dynamic compilation.[53][54] During the offline stage, an optimal spill set is first gathered using Integer Linear Programming. Then, live ranges are annotated using the compressAnnotation algorithm which relies on the previously identified optimal spill set. Register allocation is performed afterwards during the online stage, based on the data collected in the offline phase.[55]

In 2007, Bouchez et al. suggested as well to split the register allocation in different stages, having one stage dedicated to spilling, and one dedicated to coloring and coalescing.[56]

Comparison between the different techniques

Several metrics have been used to assess the performance of one register allocation technique against the other. Register allocation has typically to deal with a trade-off between code quality, i.e. code that executes quickly, and analysis overhead, i.e. the time spent determining analyzing the source code to generate code with optimized register allocation. From this perspective, execution time of the generated code and time spent in liveness analysis are relevant metrics to compare the different techniques.[57]

Once relevant metrics have been chosen, the code on which the metrics will be applied should be available and relevant to the problem, either by reflecting the behavior of real-world application, or by being relevant to the particular problem the algorithm wants to address. The more recent articles about register allocation uses especially the Dacapo benchmark suite.[58]

See also

- Strahler number, the minimum number of registers needed to evaluate an expression tree.[59]

- Register (keyword), the hint in C and C++ for a variable to be placed in a register.

References

- Ditzel & McLellan 1982, p. 48.

- Runeson & Nyström 2003, p. 242.

- Eisl et al. 2016, p. 14:1.

- Chaitin et al. 1981, p. 47.

- Eisl et al. 2016, p. 1.

- "Latency Comparison Numbers in computer/network". blog.morizyun.com. 6 January 2018. Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- Braun & Hack 2009, p. 174.

- Koes & Goldstein 2009, p. 21.

- Bouchez, Darte & Rastello 2007b, p. 103.

- Colombet, Brandner & Darte 2011, p. 26.

- "Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual, Section 3.4.1" (PDF). Intel. May 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-25.

- "32-bit PowerPC function calling conventions".

- Bouchez, Darte & Rastello 2006, p. 4.

- Horwitz et al. 1966, p. 43.

- Farach & Liberatore 1998, p. 566.

- Eisl et al. 2017, p. 92.

- Eisl, Leopoldseder & Mössenböck 2018, p. 1.

- Briggs, Cooper & Torczon 1992, p. 316.

- Poletto & Sarkar 1999, p. 896.

- Runeson & Nyström 2003, p. 241.

- Book 1975, p. 618–619.

- Colombet, Brandner & Darte 2011, p. 1.

- Smith, Ramsey & Holloway 2004, p. 277.

- Cavazos, Moss & O’Boyle 2006, p. 124.

- Runeson & Nyström 2003, p. 240.

- Poletto & Sarkar 1999, p. 895.

- Poletto & Sarkar 1999, p. 902.

- Wimmer & Mössenböck 2005, p. 132.

- Johansson & Sagonas 2002, p. 102.

- The Evolution of ART - Google I/O 2016. Google. 25 May 2016. Event occurs at 3m47s.

- Paleczny, Vick & Click 2001, p. 1.

- Poletto & Sarkar 1999, p. 899.

- Eisl et al. 2016, p. 2.

- Traub, Holloway & Smith 1998, p. 143.

- Traub, Holloway & Smith 1998, p. 141.

- Poletto & Sarkar 1999, p. 897.

- Wimmer & Franz 2010, p. 170.

- Mössenböck & Pfeiffer 2002, p. 234.

- Mössenböck & Pfeiffer 2002, p. 233.

- Mössenböck & Pfeiffer 2002, p. 229.

- Rogers 2020.

- Chaitin 1982, p. 90.

- Ahn & Paek 2009, p. 7.

- Park & Moon 2004, p. 736.

- Chaitin 1982, p. 99.

- Park & Moon 2004, p. 738.

- Briggs, Cooper & Torczon 1994, p. 433.

- George & Appel 1996, p. 212.

- Park & Moon 2004, p. 741.

- Eisl et al. 2017, p. 11.

- Cavazos, Moss & O’Boyle 2006, p. 124-127.

- Eisl et al. 2016, p. 4.

- Diouf et al. 2010, p. 66.

- Cohen & Rohou 2010, p. 1.

- Diouf et al. 2010, p. 72.

- Bouchez, Darte & Rastello 2007a, p. 1.

- Poletto & Sarkar 1999, p. 901-910.

- Blackburn et al. 2006, p. 169.

- Flajolet, Raoult & Vuillemin 1979.

Sources

- Ahn, Minwook; Paek, Yunheung (2009). "Register coalescing techniques for heterogeneous register architecture with copy sifting". ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems. 8 (2): 1–37. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.615.5767. doi:10.1145/1457255.1457263. ISSN 1539-9087. S2CID 14143277.

- Aho, Alfred V.; Lam, Monica S.; Sethi, Ravi; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (2006). Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools (second ed.). Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 978-0321486813.

- Appel, Andrew W.; George, Lal (2001). "Optimal spilling for CISC machines with few registers". Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN 2001 conference on Programming language design and implementation - PLDI '01. pp. 243–253. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.37.8978. doi:10.1145/378795.378854. ISBN 978-1581134148. S2CID 1380545.

- Barik, Rajkishore; Grothoff, Christian; Gupta, Rahul; Pandit, Vinayaka; Udupa, Raghavendra (2007). "Optimal Bitwise Register Allocation Using Integer Linear Programming". Languages and Compilers for Parallel Computing. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4382. pp. 267–282. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.75.6911. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72521-3_20. ISBN 978-3-540-72520-6.

- Bergner, Peter; Dahl, Peter; Engebretsen, David; O'Keefe, Matthew (1997). "Spill code minimization via interference region spilling". Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN 1997 conference on Programming language design and implementation - PLDI '97. pp. 287–295. doi:10.1145/258915.258941. ISBN 978-0897919074. S2CID 16952747.

- Blackburn, Stephen M.; Guyer, Samuel Z.; Hirzel, Martin; Hosking, Antony; Jump, Maria; Lee, Han; Eliot, J.; Moss, B.; Phansalkar, Aashish; Stefanović, Darko; VanDrunen, Thomas; Garner, Robin; von Dincklage, Daniel; Wiedermann, Ben; Hoffmann, Chris; Khang, Asjad M.; McKinley, Kathryn S.; Bentzur, Rotem; Diwan, Amer; Feinberg, Daniel; Frampton, Daniel (2006). "The DaCapo benchmarks". Proceedings of the 21st annual ACM SIGPLAN conference on Object-oriented programming systems, languages, and applications - OOPSLA '06. p. 169. doi:10.1145/1167473.1167488. hdl:1885/33723. ISBN 978-1595933485. S2CID 9255051.

- Book, Ronald V. (December 1975). "Karp Richard M.. Reducibility among combinatorial problems. Complexity of computer computations, Proceedings of a Symposium on the Complexity of Computer Computations, held March 20-22, 1972, at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Center, Yorktown Heights, New York, edited by Miller Raymond E. and Thatcher James W., Plenum Press, New York and London 1972, pp. 85–103". The Journal of Symbolic Logic. 40 (4): 618–619. doi:10.2307/2271828. ISSN 0022-4812. JSTOR 2271828.

- Bouchez, Florent; Darte, Alain; Rastello, Fabrice (2006). "Register Allocation: What Does the NP-Completeness Proof of Chaitin et al. Really Prove? Or Revisiting Register Allocation: Why and How". Register allocation: what does the NP-Completeness proof of Chaitin et al. really prove?. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4382. pp. 2–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72521-3_21. ISBN 978-3-540-72520-6.

- Bouchez, Florent; Darte, Alain; Rastello, Fabrice (2007a). "On the Complexity of Register Coalescing". International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization (CGO'07). pp. 102–114. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.101.6801. doi:10.1109/CGO.2007.26. ISBN 978-0-7695-2764-2. S2CID 7683867.

- Bouchez, Florent; Darte, Alain; Rastello, Fabrice (2007b). "On the complexity of spill everywhere under SSA form". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 42 (7): 103–114. arXiv:0710.3642. doi:10.1145/1273444.1254782. ISSN 0362-1340.

- Braun, Matthias; Hack, Sebastian (2009). "Register Spilling and Live-Range Splitting for SSA-Form Programs". Compiler Construction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5501. pp. 174–189. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.219.5318. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-00722-4_13. ISBN 978-3-642-00721-7. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Briggs, Preston; Cooper, Keith D.; Torczon, Linda (1992). "Rematerialization". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 27 (7): 311–321. doi:10.1145/143103.143143. ISSN 0362-1340.

- Briggs, Preston; Cooper, Keith D.; Torczon, Linda (1994). "Improvements to graph coloring register allocation". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 16 (3): 428–455. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.23.253. doi:10.1145/177492.177575. ISSN 0164-0925. S2CID 6571479.

- Cavazos, John; Moss, J. Eliot B.; O’Boyle, Michael F. P. (2006). "Hybrid Optimizations: Which Optimization Algorithm to Use?". Compiler Construction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3923. pp. 124–138. doi:10.1007/11688839_12. ISBN 978-3-540-33050-9. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Chaitin, Gregory J.; Auslander, Marc A.; Chandra, Ashok K.; Cocke, John; Hopkins, Martin E.; Markstein, Peter W. (1981). "Register allocation via coloring". Computer Languages. 6 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1016/0096-0551(81)90048-5. ISSN 0096-0551.

- Chaitin, G. J. (1982). "Register allocation & spilling via graph coloring". Proceedings of the 1982 SIGPLAN symposium on Compiler construction - SIGPLAN '82. pp. 98–101. doi:10.1145/800230.806984. ISBN 978-0897910743. S2CID 16872867.

- Chen, Wei-Yu; Lueh, Guei-Yuan; Ashar, Pratik; Chen, Kaiyu; Cheng, Buqi (2018). "Register allocation for Intel processor graphics". Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization - CGO 2018. pp. 352–364. doi:10.1145/3168806. ISBN 9781450356176. S2CID 3367270.

- Cohen, Albert; Rohou, Erven (2010). "Processor virtualization and split compilation for heterogeneous multicore embedded systems". Proceedings of the 47th Design Automation Conference on - DAC '10. p. 102. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.9701. doi:10.1145/1837274.1837303. ISBN 9781450300025. S2CID 14314078.

- Colombet, Quentin; Brandner, Florian; Darte, Alain (2011). "Studying optimal spilling in the light of SSA". Proceedings of the 14th international conference on Compilers, architectures and synthesis for embedded systems - CASES '11. p. 25. doi:10.1145/2038698.2038706. ISBN 9781450307130. S2CID 8296742.

- Diouf, Boubacar; Cohen, Albert; Rastello, Fabrice; Cavazos, John (2010). "Split Register Allocation: Linear Complexity Without the Performance Penalty". High Performance Embedded Architectures and Compilers. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 5952. pp. 66–80. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.229.3988. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-11515-8_7. ISBN 978-3-642-11514-1. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Ditzel, David R.; McLellan, H. R. (1982). "Register allocation for free". Proceedings of the first international symposium on Architectural support for programming languages and operating systems - ASPLOS-I. pp. 48–56. doi:10.1145/800050.801825. ISBN 978-0897910668. S2CID 2812379.

- Eisl, Josef; Grimmer, Matthias; Simon, Doug; Würthinger, Thomas; Mössenböck, Hanspeter (2016). "Trace-based Register Allocation in a JIT Compiler". Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Principles and Practices of Programming on the Java Platform: Virtual Machines, Languages, and Tools - PPPJ '16. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1145/2972206.2972211. ISBN 9781450341356. S2CID 31845919.

- Eisl, Josef; Marr, Stefan; Würthinger, Thomas; Mössenböck, Hanspeter (2017). "Trace Register Allocation Policies" (PDF). Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Managed Languages and Runtimes - Man Lang 2017. pp. 92–104. doi:10.1145/3132190.3132209. ISBN 9781450353403. S2CID 1195601.

- Eisl, Josef; Leopoldseder, David; Mössenböck, Hanspeter (2018). "Parallel trace register allocation". Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Managed Languages & Runtimes - Man Lang '18. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1145/3237009.3237010. ISBN 9781450364249. S2CID 52137887.

- Koes, David Ryan; Goldstein, Seth Copen (2009). "Register Allocation Deconstructed". Written at Nice, France. Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Software and Compilers for Embedded Systems. SCOPES '09. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 21–30. ISBN 978-1-60558-696-0.

- Farach, Martin; Liberatore, Vincenzo (1998). "On Local Register Allocation". Written at San Francisco, California, USA. Proceedings of the Ninth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. SODA '98. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. pp. 564–573. ISBN 0-89871-410-9.

- Flajolet, P.; Raoult, J. C.; Vuillemin, J. (1979), "The number of registers required for evaluating arithmetic expressions", Theoretical Computer Science, 9 (1): 99–125, doi:10.1016/0304-3975(79)90009-4

- George, Lal; Appel, Andrew W. (1996). "Iterated register coalescing". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 18 (3): 300–324. doi:10.1145/229542.229546. ISSN 0164-0925. S2CID 12281734.

- Horwitz, L. P.; Karp, R. M.; Miller, R. E.; Winograd, S. (1966). "Index Register Allocation". Journal of the ACM. 13 (1): 43–61. doi:10.1145/321312.321317. ISSN 0004-5411. S2CID 14560597.

- Johansson, Erik; Sagonas, Konstantinos (2002). "Linear Scan Register Allocation in a High-Performance Erlang Compiler". Practical Aspects of Declarative Languages. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2257. pp. 101–119. doi:10.1007/3-540-45587-6_8. ISBN 978-3-540-43092-6. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Kurdahi, F. J.; Parker, A. C. (1987). "REAL: a program for REgister ALlocation". 24th ACM/IEEE conference proceedings on Design automation conference - DAC '87. pp. 210–215. doi:10.1145/37888.37920. ISBN 978-0818607813. S2CID 17598675.

- Mössenböck, Hanspeter; Pfeiffer, Michael (2002). "Linear Scan Register Allocation in the Context of SSA Form and Register Constraints". Compiler Construction. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2304. pp. 229–246. doi:10.1007/3-540-45937-5_17. ISBN 978-3-540-43369-9. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Nickerson, Brian R. (1990). "Graph coloring register allocation for processors with multi-register operands". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 25 (6): 40–52. doi:10.1145/93548.93552. ISSN 0362-1340.

- Paleczny, Michael; Vick, Christopher; Click, Cliff (2001). "The Java HotSpot Server Compiler". Proceedings of the Java Virtual Machine Research and Technology Symposium (JVM01). Monterey, California, USA. pp. 1–12. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.106.1919.

- Park, Jinpyo; Moon, Soo-Mook (2004). "Optimistic register coalescing". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 26 (4): 735–765. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.33.9438. doi:10.1145/1011508.1011512. ISSN 0164-0925. S2CID 15969885.

- Poletto, Massimiliano; Sarkar, Vivek (1999). "Linear scan register allocation". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 21 (5): 895–913. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.27.2462. doi:10.1145/330249.330250. ISSN 0164-0925. S2CID 18180752.

- Rogers, Ian (2020). "Efficient global register allocation". arXiv:2011.05608 [cs.PL].

- Runeson, Johan; Nyström, Sven-Olof (2003). "Retargetable Graph-Coloring Register Allocation for Irregular Architectures". Software and Compilers for Embedded Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2826. pp. 240–254. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.6.6186. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-39920-9_17. ISBN 978-3-540-20145-8. ISSN 0302-9743.

- Smith, Michael D.; Ramsey, Norman; Holloway, Glenn (2004). "A generalized algorithm for graph-coloring register allocation". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 39 (6): 277. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.71.9532. doi:10.1145/996893.996875. ISSN 0362-1340.

- Traub, Omri; Holloway, Glenn; Smith, Michael D. (1998). "Quality and speed in linear-scan register allocation". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 33 (5): 142–151. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.52.8730. doi:10.1145/277652.277714. ISSN 0362-1340.

- Wimmer, Christian; Mössenböck, Hanspeter (2005). "Optimized interval splitting in a linear scan register allocator". Proceedings of the 1st ACM/USENIX international conference on Virtual execution environments - VEE '05. p. 132. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.394.4054. doi:10.1145/1064979.1064998. ISBN 978-1595930477. S2CID 494490.

- Wimmer, Christian; Franz, Michael (2010). "Linear scan register allocation on SSA form". Proceedings of the 8th annual IEEE/ ACM international symposium on Code generation and optimization - CGO '10. p. 170. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.162.2590. doi:10.1145/1772954.1772979. ISBN 9781605586359. S2CID 1820765.

External links

- A Tutorial on Integer Programming

- Conference Integer Programming and Combinatorial Optimization, IPCO

- The Aussois Combinatorial Optimization Workshop

- Bosscher, Steven; and Novillo, Diego. GCC gets a new Optimizer Framework. An article about GCC's use of SSA and how it improves over older IRs.

- The SSA Bibliography. Extensive catalogue of SSA research papers.

- Zadeck, F. Kenneth. "The Development of Static Single Assignment Form", December 2007 talk on the origins of SSA.

- VV.AA. "SSA-based Compiler Design" (2014)

- Citations from CiteSeer

- Optimization manuals by Agner Fog - documentation about x86 processor architecture and low-level code optimization