Pudendal nerve

The pudendal nerve is the main nerve of the perineum.[1]: 274 It is a mixed (motor and sensory) nerve and also conveys sympathetic autonomic fibers. It carries sensation from the external genitalia of both sexes and the skin around the anus and perineum, as well as the motor supply to various pelvic muscles, including the male or female external urethral sphincter and the external anal sphincter.

| Pudendal nerve | |

|---|---|

Pudendal nerve, course and branches in a male. | |

Cross-section of female pelvis in which nerve emerges from S2, S3, and S4 extends between the uterus and the anus and into labium minora, labium majora and the clitoris | |

| Details | |

| From | Sacral nerves S2, S3, S4 |

| To | Inferior rectal nerves perineal nerve dorsal nerve of the penis dorsal nerve of the clitoris |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Nervus pudendus |

| MeSH | D060525 |

| TA98 | A14.2.07.037 |

| TA2 | 6554 |

| FMA | 19037 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

If damaged, most commonly by childbirth, loss of sensation or fecal incontinence may result. The nerve may be temporarily anesthetized, called pudendal anesthesia or pudendal block.

The pudendal canal that carries the pudendal nerve is also known by the eponymous term "Alcock's canal", after Benjamin Alcock, an Irish anatomist who documented the canal in 1836.

Structure

Origin

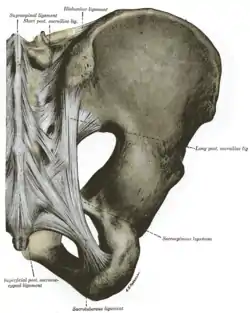

The pudendal nerve is paired, meaning there are two nerves, one on the left and one on the right side of the body. Each is formed as three roots immediately converge above the upper border of the sacrotuberous ligament and the coccygeus muscle.[2] The three roots become two cords when the middle and lower root join to form the lower cord, and these in turn unite to form the pudendal nerve proper just proximal to the sacrospinous ligament.[3] The three roots are derived from the ventral rami of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th sacral spinal nerves, with the primary contribution coming from the 4th.[2][4]: 215 [5]: 157

Course and relations

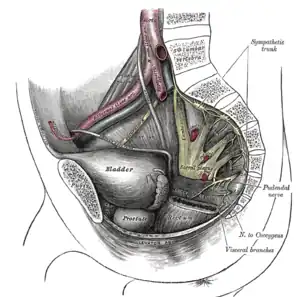

The pudendal nerve passes between the piriformis muscle and coccygeus (ischiococcygeus) muscles and leaves the pelvis through the lower part of the greater sciatic foramen.[2] It crosses over the lateral part of the sacrospinous ligament and reenters the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen. After reentering the pelvis, it accompanies the internal pudendal artery and internal pudendal vein upwards and forwards along the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa, being contained in a sheath of the obturator fascia termed the pudendal canal, along with the internal pudendal blood vessels.[6]: 8

Branches

Inside the pudendal canal, the nerve divides into branches, first giving off the inferior rectal nerve, then the perineal nerve, before continuing as the dorsal nerve of the penis (in males) or the dorsal nerve of the clitoris (in females).[6]: 34

Nucleus

The nerve is a major branch of the sacral plexus,[7]: 950 with fibers originating in Onuf's nucleus in the sacral region of the spinal cord.[3]

Variation

The pudendal nerve may vary in its origins. For example, the pudendal nerve may actually originate in the sciatic nerve.[8] Consequently, damage to the sciatic nerve can affect the pudendal nerve as well. Sometimes dorsal rami of the first sacral nerve contribute fibers to the pudendal nerve, and even more rarely S5.[3]

Function

The pudendal nerve has both motor (control of muscles) and sensory functions. It also carres sympathetic autonomic fibers (but not parasympathetic fibers).[9][10]: 1738

Sensory

The pudendal nerve supplies sensation to the penis in males, and to the clitoris in females, which travels through the branches of both the dorsal nerve of the penis and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris.[11]: 422 The posterior scrotum in males and the labia in females are also supplied, via the posterior scrotal nerves (males) or posterior labial nerves (females). The pudendal nerve is one of several nerves supplying sensation to these areas.[12] Branches also supply sensation to the anal canal.[6]: 8 By providing sensation to the penis and the clitoris, the pudendal nerve is responsible for the afferent component of penile erection and clitoral erection.[13] : 147

Motor

Branches innervate muscles of the perineum and the pelvic floor; namely, the bulbospongiosus and the ischiocavernosus muscles respectively[12], the levator ani muscle (including the Iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, puborectalis and either pubovaginalis in females or puboprostaticus in males)[11]: 422 [14] the external anal sphincter (via the inferior anal branch),[6]: 7 and male or female external urethral sphincter.[11]: 424–425

As it functions to innervate the external urethral sphincter it is responsible for the tone of the sphincter mediated via acetylcholine release. This means that during periods of increased acetylcholine release the skeletal muscle in the external urethral sphincter contracts, causing urinary retention. Whereas in periods of decreased acetylcholine release the skeletal muscle in the external urethral sphincter relaxes, allowing voiding of the bladder to occur.[15] (Unlike the internal sphincter muscle, the external sphincter is made of skeletal muscle, therefore it is under voluntary control of the somatic nervous system.)

It is also responsible for ejaculation.[16]

Clinical significance

Anesthesia

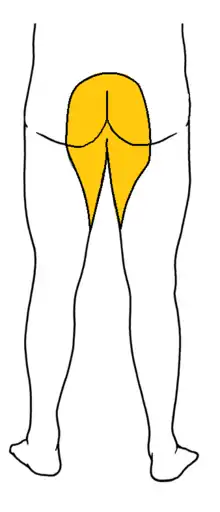

A pudendal nerve block, also known as a saddle nerve block, is a local anesthesia technique used in an obstetric procedure to anesthetize the perineum during labor.[17] In this procedure, an anesthetic agent such as lidocaine is injected through the inner wall of the vagina about the pudendal nerve.[18] Abnormal loss of sensation in the same region as a medical symptom is also sometimes termed saddle anesthesia.

Damage

The pudendal nerve can be compressed or stretched, resulting in temporary or permanent neuropathy. Injury to the pudendal nerve manifests more as sensory problems (pain or alteration/loss of sensation) rather than loss of muscle control.[9] Irreversible nerve injury may occur when nerves are stretched by 12% or more of their normal length.[6]: 655 If the pelvic floor is over-stretched, acutely (e.g. prolonged or difficult childbirth) or chronically (e.g. chronic straining during defecation caused by constipation), the pudendal nerve is vulnerable to stretch-induced neuropathy.[6]: 655 After repeated traction of the pudendal nerve, it starts to be replaced by fibrous tissue with subsequent loss of function.[19] Pudendal nerve entrapment, also known as Alcock canal syndrome, is very rare and is associated with professional cycling.[20] Systemic diseases such as diabetes and multiple sclerosis can damage the pudendal nerve via demyelination or other mechanisms.[6]: 37 A pelvic tumor (most notably a large sacrococcygeal teratoma), or surgery to remove the tumor, can also cause permanent damage.[21]

Unilateral pudendal nerve neuropathy inconsistently causes fecal incontinence in some, but not others. This is because crossover innervation of the external anal sphincter occurs in some individuals.[6]: 34 There is significant overlap of the innervation of the external anal sphincter from the pudendal nerves of both sides.[19] This allows partial re-innervation from the opposite side after nerve injury.[19]

Imaging

The pudendal nerve is difficult to visualize on routine CT or MR imaging, however under CT guidance, a needle may be placed adjacent to the pudendal neurovascular bundle. The ischial spine, an easily identifiable structure on CT, is used as the level of injection. A spinal needle is advanced via the gluteal muscles and advanced within several millimeters of the ischial spine. Contrast (X-ray dye) is then injected, highlighting the nerve in the canal and allowing for confirmation of correct needle placement. The nerve may then be injected with cortisone and local anesthetic to confirm and also treat chronic pain of the external genitalia (known as vulvodynia in females), pelvic and anorectal pain.[22][23]

Nerve latency testing

The time taken for a muscle supplied by the pudendal nerve to contract in response to an electrical stimulus applied to the sensory and motor fibers can be quantified. Increased conduction time (terminal motor latency) signifies damage to the nerve.[24]: 46 2 stimulating electrodes and 2 measuring electrodes are mounted on the examiner's gloved finger ("St Mark's electrode").[24]: 46

History

The term pudendal comes from Latin pudenda, meaning external genitals, derived from pudendum, meaning "parts to be ashamed of".[25] The pudendal canal is also known by the eponymous term "Alcock's canal", after Benjamin Alcock, an Irish anatomist who documented the canal in 1836. Alcock documented the existence of the canal and pudendal nerve in a contribution about iliac arteries in Robert Bentley Todd's "The Cyclopaedia of Anatomy and Physiology".[26]

Additional images

The male pelvis, showing the pudendal nerve (centre right)

The male pelvis, showing the pudendal nerve (centre right) Schematic showing the structures innervated by the pudendal nerve

Schematic showing the structures innervated by the pudendal nerve Diagram of the course of the pudendal nerve in the male pelvis

Diagram of the course of the pudendal nerve in the male pelvis

See also

References

- AMR Agur; AF Dalley; JCB Grant (2013). Grant's atlas of anatomy (13th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-60831-756-1.

- Standring S (editor in chief) (2004). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (39th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-443-06676-4.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Shafik, A; el-Sherif, M; Youssef, A; Olfat, ES (1995). "Surgical anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its clinical implications". Clinical Anatomy. 8 (2): 110–5. doi:10.1002/ca.980080205. PMID 7712320. S2CID 26706414.

- Moore, Keith L. Moore, Anne M.R. Agur; in collaboration with and with content provided by Arthur F. Dalley II; with the expertise of medical illustrator Valerie Oxorn and the developmental assistance of Marion E. (2007). Essential clinical anatomy (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Russell RM (2006). Examination of peripheral nerve injuries an anatomical approach. Stuttgart: Thieme. ISBN 978-3-13-143071-7.

- Wolff BG; et al., eds. (2007). The ASCRS textbook of colon and rectal surgery. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-24846-2.

- TL King; MC Brucker; JM Kriebs; JO Fahey (2013). Varney's midwifery (Fifth ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-284-02542-2.

- Nayak, Soubhagya R.; Madhan Kumar, S.J.; Krishnamurthy, Ashwin; Latha Prabhu, V.; D'costa, Sujatha; Jetti, Raghu (November 2006). "Unusual origin of dorsal nerve of penis and abnormal formation of pudendal nerve—Clinical significance". Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 188 (6): 565–566. doi:10.1016/j.aanat.2006.06.011. PMID 17140150.

- Kaur, J; Leslie, SW; Singh, P (January 2022). "Pudendal Nerve Entrapment Syndrome". PMID 31334992.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Neill, editor-in-chief, Jimmy D. (2006). Knobil and Neill's physiology of reproduction (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-515400-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- Ort, Bruce Ian Bogart, Victoria (2007). Elsevier's integrated anatomy and embryology. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-3165-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)|page=Neurovascular Bundles of the Perineum - Babayan, Mike B. Siroky, Robert D. Oates, Richard K. (2004). Handbook of urology diagnosis and therapy (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-4221-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Guaderrama, Noelani M.; Liu, Jianmin; Nager, Charles W.; Pretorius, Dolores H.; Sheean, Geoff; Kassab, Ghada; Mittal, Ravinder K. (October 2005). "Evidence for the Innervation of Pelvic Floor Muscles by the Pudendal Nerve". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 106 (4): 774–781. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000175165.46481.a8. PMID 16199635. S2CID 20663667.

- Fowler, CJ; Griffiths, D; de Groat, WC (June 2008). "The neural control of micturition". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 (6): 453–66. doi:10.1038/nrn2401. PMC 2897743. PMID 18490916.

- Penson, David F. (2002). Male Sexual Function: A Guide to Clinical Management. Annals of Internal Medicine.

- Lynna Y. Littleton; Joan Engebretson (2002). Maternal, Neonatal, and Women's Health Nursing, Volume 1. Cengage Learning. p. 727.

- Satpathy, Hemant K.; et al. Isaacs, Christine; et al. (eds.). "Transvaginal Pudendal Nerve Block". WebMD LLC. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- Steele SR, Hull TL, Hyman N, Maykel JA, Read TE, Whitlow CB (20 November 2021). The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery (4th ed.). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-66049-9.

- Mellion MB (January 1991). "Common cycling injuries. Management and prevention". Sports Med. 11 (1): 52–70. doi:10.2165/00007256-199111010-00004. PMID 2011683. S2CID 20149549.

- Lim, Jit F.; Tjandra, Joe J.; Hiscock, Richard; Chao, Michael W. T.; Gibbs, Peter (2006). "Preoperative Chemoradiation for Rectal Cancer Causes Prolonged Pudendal Nerve Terminal Motor Latency". Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 49 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1007/s10350-005-0221-7. PMID 16292664. S2CID 30584236.

- Calvillo O, Skaribas IM, Rockett C.; Skaribas; Rockett (2000). "Computed tomography-guided pudendal nerve block. A new diagnostic approach to long-term anoperineal pain: a report of two cases". Reg Anesth Pain Med. 25 (4): 420–3. doi:10.1053/rapm.2000.7620. PMID 10925942. S2CID 1622253.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hough DM, Wittenberg KH, Pawlina W, Maus TP, King BF, Vrtiska TJ, Farrell MA, Antolak SJ Jr.; Wittenberg; Pawlina; Maus; King; Vrtiska; Farrell; Antolak Jr (2003). "Chronic perineal pain caused by pudendal nerve entrapment: anatomy and CT-guided perineural injection technique". Am J Roentgenol. 181 (2): 561–7. doi:10.2214/ajr.181.2.1810561. PMID 12876048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - G.A. Santoro, A.P. Wieczorek, C.I. Bartram (editors) (2010). Pelvic floor disorders imaging and multidisciplinary approach to management. Dordrecht: Springer. ISBN 978-88-470-1542-5.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Harper, Douglas. "Pudendum". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- Oelhafen, Kim; Shayota, Brian J.; Muhleman, Mitchel; Klaassen, Zachary; Tubbs, R. Shane; Loukas, Marios (September 2013). "Benjamin Alcock (1801–?) and his canal". Clinical Anatomy. 26 (6): 662–666. doi:10.1002/ca.22080. PMID 22488487. S2CID 33298520.

External links

- Anatomy figure: 41:04-11 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Inferior view of female perineum, branches of the internal pudendal artery."

- figures/chapter_32/32-2.HTM: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School

- figures/chapter_32/32-3.HTM: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-female-17—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Diagnosis and treatment at www.nervemed.com

- www.pudendal.com

- Pudendal nerve entrapment at chronicprostatitis.com Archived 7 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- CT sequence showing a pudendal nerve block. Archived 22 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine