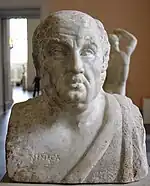

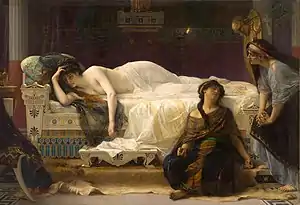

Phaedra (Seneca)

Phaedra is a Roman tragedy written by philosopher and dramatist Lucius Annaeus Seneca before 54 A.D. Its 1,280 lines of verse tell the story of Phaedra, wife of King Theseus of Athens and her consuming lust for her stepson Hippolytus. Based on Greek mythology and the tragedy Hippolytus by Euripides, Seneca's Phaedra is one of several artistic explorations of this tragic story. Seneca portrays Phaedra as self-aware and direct in the pursuit of her stepson, while in other treatments of the myth, she is more of a passive victim of fate. This Phaedra takes on the scheming nature and the cynicism often assigned to the nurse character.

Phaedra and Hippolytus, c. 290 AD | |

| Author | Lucius Annaeus Seneca |

|---|---|

| Country | Rome |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Set in | Athens |

Publication date | 1st century |

| Text | Phaedra at Wikisource |

When Seneca's plays were first revived during the Renaissance, the work that soon came to be known as Phaedra was titled Hippolytus.[1] It was presented in Latin in Rome in 1486.[2]

The play has influenced drama over the succeeding two millennia, particularly the works of Shakespeare and dramas of 16th- and 17th-century France. Other notable dramatic versions of the Phaedra story that were influenced by Seneca's version include Phèdre by Jean Racine and Phaedra's Love by Sarah Kane. Most recently, an reimagined adaptation of Phaedra by Simon Stone was produced at the National Theatre; the company included Janet McTeer, Assaad Bouab and Mackenzie Davis. Seneca's play continues to be performed today.

Major themes in Phaedra include the laws of nature as interpreted according to stoic philosophy, animal imagery and hunting and the damaging effects of the sexual transgressions of mothers and stepmothers.

Characters

- Hippolytus

- Phaedra

- nutrix (nurse)

- Chorus

- Theseus

- nuntius (messenger)

Plot summary

Lines 1–423

Hippolytus, son of King Theseus of Athens, leaves his palace at dawn to go boar-hunting. He prays to the virgin goddess Diana for success in the hunt.

His step-mother Phaedra, wife of Theseus and daughter of King Minos of Crete, soon appears in front of the palace lamenting her fate. Her husband has been gone for years after journeying to capture Persephone from the underworld. Phaedra has been left alone to care for the palace, and she finds herself pining for the forests and the hunt. Wondering what is causing her desire for the forest glades, she reflects on her mother, Pasiphaë, grand-daughter of Helios , who was cursed to fall in love with a bull and give birth to a monster, the Minotaur. Phaedra wonders if she is as doomed as her mother was.

Phaedra's aged nurse interjects that Phaedra should control the passions she feels, for love can be terribly destructive. Phaedra explains that she is gripped by an uncontrollable lust for Hippolytus, and that her passion has defeated her reason. Hippolytus, however, detests women in general and Phaedra in particular. Phaedra declares that she will commit suicide. The nurse begs Phaedra not to end her life and promises to help her in her love, saying: "Mine is the task to approach the savage youth and bend the cruel man's relentless will."

After the Chorus sings of the power of love, Phaedra goes into an emotional frenzy, and the nurse begs the goddess Diana to soften Hippolytus' heart and make him fall in love with Phaedra.

Lines 424–834

Hippolytus returns from hunting and, seeing Phaedra's nurse, asks her why she looks so sullen. The nurse replies that Hippolytus should "show [him]self less harsh", enjoy life, and seek the company of women. Hippolytus responds that life is most innocent and free when spent in the wild. Hippolytus adds that stepmothers "are no whit more merciful than beasts". He finds women wicked and points to Medea as an example. "Why make the crime of few the blame of all?" the nurse asks. She argues that love can often change stubborn dispositions. Still, Hippolytus maintains his steadfast hatred of womankind.

Phaedra appears, swoons and collapses. Hippolytus wakes her. When he asks why she is so miserable, she decides to confess her feelings. Phaedra subtly suggests that Hippolytus should take his father's place, as Theseus will likely never return from the underworld. Hippolytus agrees, offering to fill his father's shoes while awaiting his return. Phaedra then declares her love for Hippolytus. Aghast, he cries out that he is "guilty", for he has "stirred [his] stepmother to love". He then rails against what he perceives as Phaedra's terrible crime. He draws his sword to kill Phaedra, but upon realizing this is what she wants, he casts the weapon away and flees into the forest.

"Crime must be concealed by crime", the nurse decides, and plots with Phaedra to accuse Hippolytus of incestuous desire. Phaedra cries out to the citizens of Athens for help, and accuses Hippolytus of attacking her in lust. The Chorus interjects, praising Hippolytus' beauty but noting that beauty is subject to the wiles of time. The Chorus then condemns Phaedra's wicked scheme. It is then that Theseus appears, newly returned from the underworld.

Lines 835–1280

The nurse informs Theseus that Phaedra has resolved to die and he asks why, especially now that her husband has come back. The nurse explains that Phaedra will tell no one the cause of her grief. Theseus enters the palace and sees Phaedra clutching a sword, ready to slay herself. He asks her why she is in such a state, but she responds only with vague allusions to a "sin" she has committed.

Theseus orders the nurse to be bound in chains and tormented until she confesses her mistress' secret. Phaedra intervenes, telling her husband that she has been raped and that the "destroyer of [her] honor" is the one whom Theseus would least expect. She points to the sword Hippolytus left behind. Theseus, in a rage, summons his father Neptune to destroy Hippolytus. The Chorus asks the heavens why they do not reward the innocent and punish the guilty and evil. The Chorus asserts that the order of the world has become skewed: "wretched poverty dogs the pure, and the adulterer, strong in wickedness, reigns supreme."

A Messenger arrives to inform Theseus that Hippolytus is dead. Out of the ocean's depths, a monstrous bull appeared before Hippolytus' horse-drawn chariot. Hippolytus lost control of his terrified horses, and his limbs became entwined in the reins. His body was dragged through the forest, and his limbs were torn asunder. Theseus breaks into tears. Although he wished death upon his son, hearing of it causes him to despair. The Chorus proclaims that the gods most readily target mortals of wealth or power, while "the low-roofed, common home ne'er feels [Jove's] mighty blasts".

Phaedra condemns Theseus for his harshness and turns to Hippolytus' mangled corpse, crying: "Whither is thy glorious beauty fled?" She reveals that she had falsely accused Hippolytus of her own crime, falls on her sword and dies. Theseus is despondent. He orders that Hippolytus be given a proper burial. Pointing to Phaedra's corpse, he declares: "As for her, let her be buried deep in earth, and heavy may the soil lie on her unholy head!"

Source material

The story of the Hippolytus–Phaedra relationship is derived from one of several ancient Greek myths revolving around the archetypal Athenian hero, Theseus. The Greek playwright Euripides wrote two versions of the tragedy, the lost Hippolytus Veiled and the extant Hippolytus (428 B.C.E.).[3] It is thought that Hippolytus Veiled was not favorably received in the tragic competition of the Dionysean Festival, as it portrayed Phaedra as brazen and forward in response to her her husband's philandering, and showed her making a directly sexual proposition to her husband's son. Athenians tended to disapprove of women being portrayed as expressing such illicit passions. It is thought by some that Euripides wrote Hippolytus in order to correct his first version, and present both Phaedra and Hippolytus as chaste. The sources that have survived do not unequivocally confirm these assumptions, and alternate theories have been advanced.[4]

While historians believe that Phaedra was heavily influenced by Euripides' Hippolytus, there are several differences in plot and tone.[5] Literary scholar Albert S. Gérard states that, unlike the Phaedra of Hippolytus, Seneca's Phaedra is a thoughtful and intelligent character that acknowledges the improper and amoral nature of her feelings towards her stepson, yet still pursues him.[6] In Euripides' iteration of the play, it is the Nurse that informs Hippolytus of Phaedra's love for him. In Seneca's version, Phaedra personally conveys her desires to her stepson. Gérard claims that by transferring much of the scheming, "cynical insights," and "pragmatic advice" from the Nurse to Phaedra, Seneca implies that Phaedra is responsible for her actions, and she is aware that her behavior deviates from accepted principles of human morality.[6] In another departure from Euripides' Hippolytus, Phaedra, rather than committing suicide immediately after Hippolytus rejects her advances, is filled with remorse after Hippolytus has been killed and stabs herself. Gérard claims that these plot differences show a historical shift from the Greek "shame culture" priority of preserving one's reputation, to the Roman "guilt culture" priority of repentance.[6]

Historical context and reception

During his life, Seneca (4–5 B.C.E.–65 C.E.) was famous for his writings on Stoic philosophy and rhetoric and became "one of the most influential men in Rome" when his student, Nero, was named emperor in 54 C.E.[5] Phaedra is thought to be one of Seneca's earlier works, most likely written before 54 C.E.[3] Historians generally agree that Seneca did not intend for his plays to be performed in the public theaters of Rome, but rather privately recited for gatherings of fashionable and educated audiences. Since Phaedra was not meant to be acted, historian F.L. Lucas states that Seneca's writing, "tends to have less and less action, and the whole burden is thrown upon the language".[7]

The structure and style of Senecan tragedies such as Phaedra have exerted great influence on drama throughout the ages, particularly on tragedy in the time of Shakespeare. Technical devices such as asides and soliloquies, in addition to a focus on the supernatural and the destructive power of obsessive emotions, can all be traced back to Seneca.[5] The influence of Phaedra in particular can further be seen in dramas of 16th and 17th century France with Robert Garnier's Hippolyte (1573) and Racine's Phèdre (1677). According to historian Helen Slaney, Senecan tragedy "virtually disappeared" in the 18th century as drama became more regulated and "sensibility supplanted horror".[8] Seneca's Phaedra saw a resurgence of influence in the 20th century with productions of Tony Harrison's Phaedra Britannica (1975), Sarah Kane's Phaedra's Love (1996). According to Slaney, today the dramas of Seneca "remain a touchstone for creative practitioners seeking to represent the unrepresentable".[8]

Themes and analysis

- The laws of nature

In addition to his work as a dramatist, Seneca was a Stoic philosopher. The Stoics believed that reason and the laws of nature must always govern human behavior.[9] In making the conscious choice to pursue her sinful passion for her stepson, Phaedra disturbs the laws of nature to such a degree that, according to Seneca's Stoic ideology, only her death can restore the cosmic order. Likewise, Hippolytus feels that Phaedra's lust has tainted him, and he does not wish to live in a world that is no longer governed by moral law.[10] Hippolytus does not himself represent Stoic ideals. He denies ordinary human social bonds and isolates himself from society, thus making his moral existence unstable, especially in the face of his stepmother's unnatural advances.[10]

- Animal imagery and hunting

The opening scene of Phaedra shows Hippolytus with his men preparing for the hunt. According to scholar Alin Mocanu, Seneca chooses to describe their preparations with vocabulary, "that would be appropriate both to a hunt for animals and to an erotic hunt".[11] Later in the play, Hippolytus transitions from hunter to prey, as Phaedra becomes the predator in the pursuit of her stepson. Both Phaedra and her nurse describe Hippolytus as if he were a wild animal, referring to him as "young beast" and "ferocious".[11] Phaedra, in turn, refers to herself as a hunter: "My joy is to follow in pursuit of the startled beasts and with soft hand to hurl stiff javelins."[12] The centrality of hunting to the plot is, furthermore, demonstrated by the fact that Diana, the goddess of the hunt, is the only deity who has an altar on stage, and the altar is important enough to be referenced four times in the course of the play.[11]

Stepmothers and mothers

In Phaedra, Seneca addresses the pervasive Roman stereotype of the amoral and wicked stepmother. Phaedra is referred to as a stepmother four times throughout the course of the play, each time at a moment of climactic action. This is notable when compared to Euripides' Hippolytus, in which the word stepmother is never used to describe Phaedra. According to scholar Mairead McAuley, "Roman obsession with both wicked and sexually predatory stepmother figures indicates a prevailing belief that the stepmaternal role led inherently to feminine lack of control and destructive impulses."[13] It is important to note, however, that Seneca does not represent Phaedra as merely a caricature of the evil stepmother, but paints her in a more sympathetic light by showing her inner conflict and turmoil.[13]

Phaedra believes that her unnatural feelings for Hippolytus can be traced back to the transgressions of her own mother, Pasiphaë, who mated with a bull and gave birth to the Minotaur. Phaedra says, "I recognize my wretched mother's fatal cures; her love and mine know how to sin in forest depths."[12] The Nurse, however, points out that Phaedra's crime would be even worse, because Phaedra is self-aware and not a victim of fate.[13] The Nurse says, "Why heap fresh infamy upon thy house and outsin thy mother? Impious sin is worse than monstrous passion; for monstrous love thou mayest impute to fate, but crime, to character."[12] In the end, Phaedra can be seen to meet a fate similar to that of her mother, for her unnatural lust brings about the creation of the monstrous bull that dismembers Hippolytus.[13]

Productions

- 1474: Performed at Palais de Cardinal Saint Georges (France).[14]

- 1486: Staged in the Campo de' Fiori, Rome, by Giovanni Sulpizio da Veroli and Raffaele Riario, with support from the Roman Academy of Julius Pomponius Laetus, with Tommaso Inghirami in the title role.[15][16][17]

- 1509: Produced under the auspices of the Cardinal Raffaele Riario at an unknown venue (Italy).[18]

- June 27–29, 1973: Directed by Stuart Fortey and John Glucker and performed at Reed Hall Gardens (Exeter, England).[19]

- November 28–29, 1992: Directed by Mark Grant and performed at Haileybury College (Hertford, England).[20]

- January 1, 1995: Performed at Reed College (Oregon, United States).[21]

- March 1, 1997: Featuring actress Diana Rigg and performed at Almeida Theatre (London, England).[22]

- November 17, 2013: Produced by the Antaeus Company and featuring Francia DiMase as Phaedra, Daniel Bess as Hippolytus, and Tony Amendola as Theseus. The production was directed by Stephanie Shoyer and performed at the Getty Villa (Malibu, CA).[23]

See also

- Hippolyte, tragédie tournée de Sénèque, French translation

- Fedra (film), a 1956 Spanish film loosely based on Seneca's play.

- Phaedra (film), a 1962 film by Jules Dassin based on the Phaedra myth

- Phaedra (cantata), a cantata by Benjamin Britten based on the Phaedra myth

- Phaedra (opera), an opera by Hans Werner Henze based on the Phaedra myth

Notes

- Ker, James; Winston, Jessica, eds. (2012). Elizabethan Seneca: Three Tragedies. Modern Humanities Research Association. p. 279. ISBN 9780947623982.

- Benedetti, Stefano (2004). "Inghirami, Tommaso, detto Fedra". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 62. Retrieved 6 November 2019 – via Treccani.

- Coffey & Mayer, pp. 5–6

- Roisman, Hanna M. (1999). "The Veiled Hippolytus and Phaedra". Hermes. 127 (4): 397–409. JSTOR 4477328.

- Brockett, p. 43

- Gérard, pp. 25–35

- Lucas, p. 57

- Slaney, Helen. "Reception of Senecan Tragedy". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. (1989). Senecan Drama and Stoic Cosmology. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780520064454.

- Henry, D.&E. (1985). The Mask of Power, Seneca's Tragedies and Imperial Rome. Chicago, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. pp. 75–79. ISBN 0865161194.

- Mocanu, Alin (2012). "Hunting in Seneca's Phaedra". Past Imperfect. 18: 28–39.

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. "Phaedra". Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- McAule, Mairéad (2012). "Specters of Medea". Helios. 39 (1): 37–42. doi:10.1353/hel.2012.0001. S2CID 170777304.

- "Phaedra (1474)". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Bietenholz, Peter G.; Deutscher, Thomas Brian, eds. (2003). Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation. Vol. 2. University of Toronto Press. p. 224ff. ISBN 9780802085771. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Rowland, Ingrid (2019). "Tommaso 'Fedra' Inghirami". In Silver, Nathaniel (ed.). Raphael and the Pope's Librarian. Boston: Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum. pp. 30, 43–46, 51.

- "Hippolytus (1485)". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Phaedra (1509)". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Phaedra (1973)". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Phaedra (1992)". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Phaedra (1995 – 1996)". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "Phaedra (1997)". Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- "The Getty". Retrieved November 21, 2013.

Text editions

- Otto Zwierlein (ed.), Seneca Tragoedia (Oxford: Clarendon Press: Oxford Classical Texts: 1986)

- John G. Fitch Tragedies, Volume I: Hercules. Trojan Women. Phoenician Women. Medea. Phaedra (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: Loeb Classical Library: 2002)

References

- Brockett, Oscar G.; Hildy, Franklin J. (2003). History of the Theatre (Foundation ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-47360-1.

- Dupont, F. (1995). Les monstres de Sénèque. Paris: Belin.

- Gérard, Albert S. (1993). The Phaedra Syndrome: Of Shame and Guilt in Drama. Atlanta, Georgia: Rodopi.

- Grimal, P. (1965). Phædra. Paris: Erasme.

- Grimal, P. (1963). "L'originalité de Sénèque dans la tragédie de Phèdre". Revue des Études latines. XLI: 297–314.

- Lucas, F.L. (1922). Seneca and Elizabethan Tragedy. London: Cambridge at the University Press.

- Runchina, G. (1960). Tecnica drammatica e retorica nelle Tragedie di Seneca. Cagliari.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Seneca, Lucius Annaeus (1990). Michael Coffey & Roland Mayer (ed.). Phaedra. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics.

Further reading

- Bloch, David. 2007. "In Defence of Seneca’s Phaedra." Classica et Mediaevalia 58:237–257.

- Damschen, Gregor, and Andreas Heil, eds. 2014. Brill’s Companion to Seneca, Philosopher and Dramatist. Leiden, The Netherlands, and Boston: Brill.

- Davis, P. J. 1984. "The First Chorus of Seneca’s Phaedra." Latomus 43:396–401.

- Dodson-Robinson, Eric, ed. 2016. Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Senecan Tragedy: Scholarly, Theatrical, and Literary Receptions. Leiden, The Netherlands, and Boston: Brill.

- Frangoulidis, Stavros. 2009. "The Nurse as a Plot-Maker in Seneca’s Phaedra." Rivista di filologia e di istruzione classica 137:402–423.

- Hine, Harry M. 2004. "Interpretatio Stoica of Senecan Tragedy." In Sénèque le tragique: huit exposés suivis de discussions. Vandœuvres, Genève, 1–5 septembre 2003. Edited by W.-L. Liebermann, et al., 173–209. Geneva, Switzerland: Fondation Hardt.

- Littlewood, Cedric A. J. 2004. Self-Representation and Illusion in Senecan Tragedy. Oxford: Clarendon

- Mayer, Roland. 2002. Seneca: Phaedra. London: Duckworth.

- Roisman, Hanna M. 2005. "Women in Senecan tragedy." Scholia n.s. 14:72–88.

- Segal, Charles. 1986. Language and Desire in Seneca’s Phaedra. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

External links

| Library resources about Seneca's Phaedra |

- Lucius Annaeus Seneca at Theatre Database

- Original text of Phaedra in Latin

- Free English text