Pelvimetry

Pelvimetry is the measurement of the female pelvis.[1] It can theoretically identify cephalo-pelvic disproportion, which is when the capacity of the pelvis is inadequate to allow the fetus to negotiate the birth canal. However, clinical evidence indicate that all pregnant women should be allowed a trial of labor regardless of pelvimetry results.[2]

| Pelvimetry | |

|---|---|

| Purpose | measurement of female pelvis |

Indication

Theoretically, pelvimetry may identify cephalo-pelvic disproportion, which is when the capacity of the pelvis is inadequate to allow the fetus to negotiate the birth canal. However, a woman's pelvis loosens up before birth (with the help of hormones).

A Cochrane review in 2017 found that there was too little evidence to show whether X-ray pelvimetry is beneficial and safe when the baby is in cephalic presentation.[3]

A review in 2003 came to the conclusion that pelvimetry does not change the management of pregnant women, and recommended that all women should be allowed a trial of labor regardless of pelvimetry results.[2] It considered routine performance of pelvimetry to be a waste of time, a potential liability, and an unnecessary discomfort.[2]

Components

The terms used in pelvimetry are commonly used in obstetrics. Clinical pelvimetry attempts to assess the pelvis by clinical examination. Pelvimetry can also be done by radiography and MRI.

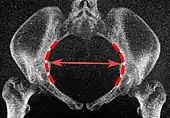

Low-dose 3D-rendered CT scans can be used for estimating the main pelvimetry parameters:[4]

| Parameter | Maximum intensity projections[5] | Thin slices | End points | Normal measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelvic inlet | Transverse diameter of the pelvic inlet |  |

Coronal plane |

The iliopectineal lines, at widest transverse distance. | 13 to 14.5 cm.[4] |

| Obstetric conjugate |  Median plane, 20 mm thick |

Same, but may require minor side-to-side scrolling to visualize both end points. | The line between the closest bony points of the sacral promontory and the pubic bone next to the symphysis | 10 to 12 cm.[4] | |

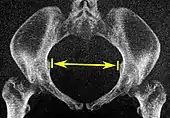

| Interspinous distance |  |

Axial plane |

The line between the closest bone points of the ischial spines | 9.5 to 11.5 cm.[6] | |

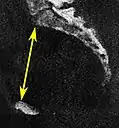

| Pelvic outlet | Sagittal pelvic outlet diameter |  |

Same, but may require minor side-to-side scrolling to visualize both end points. | The closest bony points of the sacrococcygeal joint and the pubic bone next to the symphysis. This is also called the obstetric anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet, to distinguish from the anatomic one which includes the coccyx.[7] However, the coccyx is normally pushed away during childbirth by laxity in the sacrococcygeal joint.[8] | 9.5 to 11.5 cm.[6] |

| Intertuberous diameter |  |

Axial plane |

The closest bony points of the ischial tuberosities | 10 to 12 cm.[6] | |

History

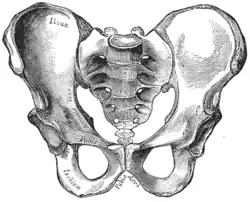

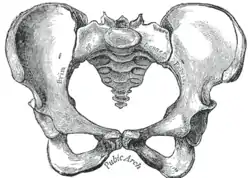

Male pelvis |

Female pelvis |

| Comparison between an android (left) and a gynecoid pelvis (right). | |

Traditional obstetrical services relied heavily on pelvimetry in the conduct of delivery in order to decide if natural or operative vaginal delivery was possible or if and when to use a cesarean section.[9] Women whose pelvises were deemed too small received caesarean sections instead of birthing naturally.

Traditional obstetrics have characterized four types of pelvises:

- Gynecoid: Ideal shape, with round to slightly oval (obstetrical inlet slightly less transverse) inlet.

- Android: triangular inlet, and prominent ischial spines, more angulated pubic arch.

- Anthropoid: the widest transverse diameter is less than the anteroposterior (obstetrical) diameter.

- Platypelloid: Flat inlet with shortened obstetrical diameter.

See also

References

- "pelvimetry" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Blackadar CS, Viera AJ (2004). "A retrospective review of performance and utility of routine clinical pelvimetry". Family Medicine. 36 (7): 505–7. PMID 15243832.

- Pattinson RC, Cuthbert A, Vannevel V (March 2017). "Pelvimetry for fetal cephalic presentations at or near term for deciding on mode of delivery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (12): CD000161. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000161.pub2. PMC 6464150. PMID 28358979.

- Salk I, Cetin A, Salk S, Cetin M (2016). "Pelvimetry by Three-Dimensional Computed Tomography in Non-Pregnant Multiparous Women Who Delivered Vaginally". Polish Journal of Radiology. 81: 219–27. doi:10.12659/PJR.896380. PMC 4865272. PMID 27231494.

- Salk, Ismail; Cetin, Ali; Salk, Sultan; Cetin, Meral (2016). "Pelvimetry by Three-Dimensional Computed Tomography in Non-Pregnant Multiparous Women Who Delivered Vaginally". Polish Journal of Radiology. 81: 219–227. doi:10.12659/PJR.896380. ISSN 0137-7183. PMC 4865272. PMID 27231494.

- Gowri V, Jain R, Rizvi S (August 2010). "Magnetic resonance pelvimetry for trial of labour after a previous caesarean section". Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 10 (2): 210–4. PMC 3074700. PMID 21509231.

- Page 94 in: Neville F. Hacker, Joseph C. Gambone, Calvin J. Hobel (2009). Hacker & Moore's Essentials of Obstetrics and Gynecology (5 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781437725162.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Page 239 in: Wayne R. Cohen, Emanuel A. Friedman (2011). Labor and Delivery Care: A Practical Guide. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119971542.

- Herbert Thoms (1946). "Yale - The Pelvic Survey". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 19 (2): 171–179. PMC 2602099. PMID 20285601.