OpenMP

OpenMP (Open Multi-Processing) is an application programming interface (API) that supports multi-platform shared-memory multiprocessing programming in C, C++, and Fortran,[3] on many platforms, instruction-set architectures and operating systems, including Solaris, AIX, FreeBSD, HP-UX, Linux, macOS, and Windows. It consists of a set of compiler directives, library routines, and environment variables that influence run-time behavior.[2][4][5]

| |

| Original author(s) | OpenMP Architecture Review Board[1] |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | OpenMP Architecture Review Board[1] |

| Stable release | 5.2

/ November 2021 |

| Operating system | Cross-platform |

| Platform | Cross-platform |

| Type | Extension to C, C++, and Fortran; API |

| License | Various[2] |

| Website | openmp |

OpenMP is managed by the nonprofit technology consortium OpenMP Architecture Review Board (or OpenMP ARB), jointly defined by a broad swath of leading computer hardware and software vendors, including Arm, AMD, IBM, Intel, Cray, HP, Fujitsu, Nvidia, NEC, Red Hat, Texas Instruments, and Oracle Corporation.[1]

OpenMP uses a portable, scalable model that gives programmers a simple and flexible interface for developing parallel applications for platforms ranging from the standard desktop computer to the supercomputer.

An application built with the hybrid model of parallel programming can run on a computer cluster using both OpenMP and Message Passing Interface (MPI), such that OpenMP is used for parallelism within a (multi-core) node while MPI is used for parallelism between nodes. There have also been efforts to run OpenMP on software distributed shared memory systems,[6] to translate OpenMP into MPI[7][8] and to extend OpenMP for non-shared memory systems.[9]

Design

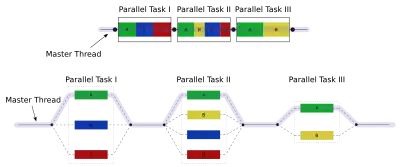

OpenMP is an implementation of multithreading, a method of parallelizing whereby a primary thread (a series of instructions executed consecutively) forks a specified number of sub-threads and the system divides a task among them. The threads then run concurrently, with the runtime environment allocating threads to different processors.

The section of code that is meant to run in parallel is marked accordingly, with a compiler directive that will cause the threads to form before the section is executed.[3] Each thread has an ID attached to it which can be obtained using a function (called omp_get_thread_num()). The thread ID is an integer, and the primary thread has an ID of 0. After the execution of the parallelized code, the threads join back into the primary thread, which continues onward to the end of the program.

By default, each thread executes the parallelized section of code independently. Work-sharing constructs can be used to divide a task among the threads so that each thread executes its allocated part of the code. Both task parallelism and data parallelism can be achieved using OpenMP in this way.

The runtime environment allocates threads to processors depending on usage, machine load and other factors. The runtime environment can assign the number of threads based on environment variables, or the code can do so using functions. The OpenMP functions are included in a header file labelled omp.h in C/C++.

History

The OpenMP Architecture Review Board (ARB) published its first API specifications, OpenMP for Fortran 1.0, in October 1997. In October the following year they released the C/C++ standard. 2000 saw version 2.0 of the Fortran specifications with version 2.0 of the C/C++ specifications being released in 2002. Version 2.5 is a combined C/C++/Fortran specification that was released in 2005.

Up to version 2.0, OpenMP primarily specified ways to parallelize highly regular loops, as they occur in matrix-oriented numerical programming, where the number of iterations of the loop is known at entry time. This was recognized as a limitation, and various task parallel extensions were added to implementations. In 2005, an effort to standardize task parallelism was formed, which published a proposal in 2007, taking inspiration from task parallelism features in Cilk, X10 and Chapel.[10]

Version 3.0 was released in May 2008. Included in the new features in 3.0 is the concept of tasks and the task construct,[11] significantly broadening the scope of OpenMP beyond the parallel loop constructs that made up most of OpenMP 2.0.[12]

Version 4.0 of the specification was released in July 2013.[13] It adds or improves the following features: support for accelerators; atomics; error handling; thread affinity; tasking extensions; user defined reduction; SIMD support; Fortran 2003 support.[14]

The current version is 5.2, released in November 2021.[15]

Note that not all compilers (and OSes) support the full set of features for the latest version/s.

Core elements

The core elements of OpenMP are the constructs for thread creation, workload distribution (work sharing), data-environment management, thread synchronization, user-level runtime routines and environment variables.

In C/C++, OpenMP uses #pragmas. The OpenMP specific pragmas are listed below.

Thread creation

The pragma omp parallel is used to fork additional threads to carry out the work enclosed in the construct in parallel. The original thread will be denoted as master thread with thread ID 0.

Example (C program): Display "Hello, world." using multiple threads.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main(void)

{

#pragma omp parallel

printf("Hello, world.\n");

return 0;

}

Use flag -fopenmp to compile using GCC:

$ gcc -fopenmp hello.c -o hello -ldl

Output on a computer with two cores, and thus two threads:

Hello, world.

Hello, world.

However, the output may also be garbled because of the race condition caused from the two threads sharing the standard output.

Hello, wHello, woorld.

rld.

Whether printf is atomic depends on the underlying implementation[16] unlike C++'s std::cout.

Work-sharing constructs

Used to specify how to assign independent work to one or all of the threads.

- omp for or omp do: used to split up loop iterations among the threads, also called loop constructs.

- sections: assigning consecutive but independent code blocks to different threads

- single: specifying a code block that is executed by only one thread, a barrier is implied in the end

- master: similar to single, but the code block will be executed by the master thread only and no barrier implied in the end.

Example: initialize the value of a large array in parallel, using each thread to do part of the work

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

int a[100000];

#pragma omp parallel for

for (int i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

a[i] = 2 * i;

}

return 0;

}

This example is embarrassingly parallel, and depends only on the value of i. The OpenMP parallel for flag tells the OpenMP system to split this task among its working threads. The threads will each receive a unique and private version of the variable.[17] For instance, with two worker threads, one thread might be handed a version of i that runs from 0 to 49999 while the second gets a version running from 50000 to 99999.

Variant directives

Variant directives is one of the major features introduced in OpenMP 5.0 specification to facilitate programmers to improve performance portability. They enable adaptation of OpenMP pragmas and user code at compile time. The specification defines traits to describe active OpenMP constructs, execution devices, and functionality provided by an implementation, context selectors based on the traits and user-defined conditions, and metadirective and declare directive directives for users to program the same code region with variant directives.

- The metadirective is an executable directive that conditionally resolves to another directive at compile time by selecting from multiple directive variants based on traits that define an OpenMP condition or context.

- The declare variant directive has similar functionality as metadirective but selects a function variant at the call-site based on context or user-defined conditions.

The mechanism provided by the two variant directives for selecting variants is more convenient to use than the C/C++ preprocessing since it directly supports variant selection in OpenMP and allows an OpenMP compiler to analyze and determine the final directive from variants and context.

// code adaptation using preprocessing directives

int v1[N], v2[N], v3[N];

#if defined(nvptx)

#pragma omp target teams distribute parallel for map(to:v1,v2) map(from:v3)

for (int i= 0; i< N; i++)

v3[i] = v1[i] * v2[i];

#else

#pragma omp target parallel for map(to:v1,v2) map(from:v3)

for (int i= 0; i< N; i++)

v3[i] = v1[i] * v2[i];

#endif

// code adaptation using metadirective in OpenMP 5.0

int v1[N], v2[N], v3[N];

#pragma omp target map(to:v1,v2) map(from:v3)

#pragma omp metadirective \

when(device={arch(nvptx)}: target teams distribute parallel for)\

default(target parallel for)

for (int i= 0; i< N; i++)

v3[i] = v1[i] * v2[i];

Clauses

Since OpenMP is a shared memory programming model, most variables in OpenMP code are visible to all threads by default. But sometimes private variables are necessary to avoid race conditions and there is a need to pass values between the sequential part and the parallel region (the code block executed in parallel), so data environment management is introduced as data sharing attribute clauses by appending them to the OpenMP directive. The different types of clauses are:

- Data sharing attribute clauses

- shared: the data declared outside a parallel region is shared, which means visible and accessible by all threads simultaneously. By default, all variables in the work sharing region are shared except the loop iteration counter.

- private: the data declared within a parallel region is private to each thread, which means each thread will have a local copy and use it as a temporary variable. A private variable is not initialized and the value is not maintained for use outside the parallel region. By default, the loop iteration counters in the OpenMP loop constructs are private.

- default: allows the programmer to state that the default data scoping within a parallel region will be either shared, or none for C/C++, or shared, firstprivate, private, or none for Fortran. The none option forces the programmer to declare each variable in the parallel region using the data sharing attribute clauses.

- firstprivate: like private except initialized to original value.

- lastprivate: like private except original value is updated after construct.

- reduction: a safe way of joining work from all threads after construct.

- Synchronization clauses

- critical: the enclosed code block will be executed by only one thread at a time, and not simultaneously executed by multiple threads. It is often used to protect shared data from race conditions.

- atomic: the memory update (write, or read-modify-write) in the next instruction will be performed atomically. It does not make the entire statement atomic; only the memory update is atomic. A compiler might use special hardware instructions for better performance than when using critical.

- ordered: the structured block is executed in the order in which iterations would be executed in a sequential loop

- barrier: each thread waits until all of the other threads of a team have reached this point. A work-sharing construct has an implicit barrier synchronization at the end.

- nowait: specifies that threads completing assigned work can proceed without waiting for all threads in the team to finish. In the absence of this clause, threads encounter a barrier synchronization at the end of the work sharing construct.

- Scheduling clauses

- schedule (type, chunk): This is useful if the work sharing construct is a do-loop or for-loop. The iterations in the work sharing construct are assigned to threads according to the scheduling method defined by this clause. The three types of scheduling are:

- static: Here, all the threads are allocated iterations before they execute the loop iterations. The iterations are divided among threads equally by default. However, specifying an integer for the parameter chunk will allocate chunk number of contiguous iterations to a particular thread.

- dynamic: Here, some of the iterations are allocated to a smaller number of threads. Once a particular thread finishes its allocated iteration, it returns to get another one from the iterations that are left. The parameter chunk defines the number of contiguous iterations that are allocated to a thread at a time.

- guided: A large chunk of contiguous iterations are allocated to each thread dynamically (as above). The chunk size decreases exponentially with each successive allocation to a minimum size specified in the parameter chunk

- IF control

- if: This will cause the threads to parallelize the task only if a condition is met. Otherwise the code block executes serially.

- Initialization

- firstprivate: the data is private to each thread, but initialized using the value of the variable using the same name from the master thread.

- lastprivate: the data is private to each thread. The value of this private data will be copied to a global variable using the same name outside the parallel region if current iteration is the last iteration in the parallelized loop. A variable can be both firstprivate and lastprivate.

- threadprivate: The data is a global data, but it is private in each parallel region during the runtime. The difference between threadprivate and private is the global scope associated with threadprivate and the preserved value across parallel regions.

- Data copying

- copyin: similar to firstprivate for private variables, threadprivate variables are not initialized, unless using copyin to pass the value from the corresponding global variables. No copyout is needed because the value of a threadprivate variable is maintained throughout the execution of the whole program.

- copyprivate: used with single to support the copying of data values from private objects on one thread (the single thread) to the corresponding objects on other threads in the team.

- Reduction

- reduction (operator | intrinsic : list): the variable has a local copy in each thread, but the values of the local copies will be summarized (reduced) into a global shared variable. This is very useful if a particular operation (specified in operator for this particular clause) on a variable runs iteratively, so that its value at a particular iteration depends on its value at a prior iteration. The steps that lead up to the operational increment are parallelized, but the threads updates the global variable in a thread safe manner. This would be required in parallelizing numerical integration of functions and differential equations, as a common example.

- Others

- flush: The value of this variable is restored from the register to the memory for using this value outside of a parallel part

- master: Executed only by the master thread (the thread which forked off all the others during the execution of the OpenMP directive). No implicit barrier; other team members (threads) not required to reach.

User-level runtime routines

Used to modify/check the number of threads, detect if the execution context is in a parallel region, how many processors in current system, set/unset locks, timing functions, etc

Environment variables

A method to alter the execution features of OpenMP applications. Used to control loop iterations scheduling, default number of threads, etc. For example, OMP_NUM_THREADS is used to specify number of threads for an application.

Implementations

OpenMP has been implemented in many commercial compilers. For instance, Visual C++ 2005, 2008, 2010, 2012 and 2013 support it (OpenMP 2.0, in Professional, Team System, Premium and Ultimate editions[18][19][20]), as well as Intel Parallel Studio for various processors.[21] Oracle Solaris Studio compilers and tools support the latest OpenMP specifications with productivity enhancements for Solaris OS (UltraSPARC and x86/x64) and Linux platforms. The Fortran, C and C++ compilers from The Portland Group also support OpenMP 2.5. GCC has also supported OpenMP since version 4.2.

Compilers with an implementation of OpenMP 3.0:

- GCC 4.3.1

- Mercurium compiler

- Intel Fortran and C/C++ versions 11.0 and 11.1 compilers, Intel C/C++ and Fortran Composer XE 2011 and Intel Parallel Studio.

- IBM XL compiler[22]

- Sun Studio 12 update 1 has a full implementation of OpenMP 3.0[23]

- Multi-Processor Computing

Several compilers support OpenMP 3.1:

- GCC 4.7[24]

- Intel Fortran and C/C++ compilers 12.1[25]

- IBM XL C/C++ compilers for AIX and Linux, V13.1[26] & IBM XL Fortran compilers for AIX and Linux, V14.1[27]

- LLVM/Clang 3.7[28]

- Absoft Fortran Compilers v. 19 for Windows, Mac OS X and Linux[29]

Compilers supporting OpenMP 4.0:

- GCC 4.9.0 for C/C++, GCC 4.9.1 for Fortran[24][30]

- Intel Fortran and C/C++ compilers 15.0[31]

- IBM XL C/C++ for Linux, V13.1 (partial)[26] & XL Fortran for Linux, V15.1 (partial)[27]

- LLVM/Clang 3.7 (partial)[28]

Several Compilers supporting OpenMP 4.5:

Partial support for OpenMP 5.0:

Auto-parallelizing compilers that generates source code annotated with OpenMP directives:

- iPat/OMP

- Parallware

- PLUTO

- ROSE (compiler framework)

- S2P by KPIT Cummins Infosystems Ltd.

- ComPar

- PragFormer

Several profilers and debuggers expressly support OpenMP:

- Intel VTune Profiler - a profiler for the x86 CPU and Xe GPU architectures

- Intel Advisor - a design assistance and analysis tool for OpenMP and MPI codes

- Allinea Distributed Debugging Tool (DDT) – debugger for OpenMP and MPI codes

- Allinea MAP – profiler for OpenMP and MPI codes

- TotalView - debugger from Rogue Wave Software for OpenMP, MPI and serial codes

- ompP – profiler for OpenMP

- VAMPIR – profiler for OpenMP and MPI code

Pros and cons

Pros:

- Portable multithreading code (in C/C++ and other languages, one typically has to call platform-specific primitives in order to get multithreading).

- Simple: need not deal with message passing as MPI does.

- Data layout and decomposition is handled automatically by directives.

- Scalability comparable to MPI on shared-memory systems.[37]

- Incremental parallelism: can work on one part of the program at one time, no dramatic change to code is needed.

- Unified code for both serial and parallel applications: OpenMP constructs are treated as comments when sequential compilers are used.

- Original (serial) code statements need not, in general, be modified when parallelized with OpenMP. This reduces the chance of inadvertently introducing bugs.

- Both coarse-grained and fine-grained parallelism are possible.

- In irregular multi-physics applications which do not adhere solely to the SPMD mode of computation, as encountered in tightly coupled fluid-particulate systems, the flexibility of OpenMP can have a big performance advantage over MPI.[37][38]

- Can be used on various accelerators such as GPGPU[39] and FPGAs.

Cons:

- Risk of introducing difficult to debug synchronization bugs and race conditions.[40][41]

- As of 2017 only runs efficiently in shared-memory multiprocessor platforms (see however Intel's Cluster OpenMP Archived 2018-11-16 at the Wayback Machine and other distributed shared memory platforms).

- Requires a compiler that supports OpenMP.

- Scalability is limited by memory architecture.

- No support for compare-and-swap.[42]

- Reliable error handling is missing.

- Lacks fine-grained mechanisms to control thread-processor mapping.

- High chance of accidentally writing false sharing code.

Performance expectations

One might expect to get an N times speedup when running a program parallelized using OpenMP on a N processor platform. However, this seldom occurs for these reasons:

- When a dependency exists, a process must wait until the data it depends on is computed.

- When multiple processes share a non-parallel proof resource (like a file to write in), their requests are executed sequentially. Therefore, each thread must wait until the other thread releases the resource.

- A large part of the program may not be parallelized by OpenMP, which means that the theoretical upper limit of speedup is limited according to Amdahl's law.

- N processors in a symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) may have N times the computation power, but the memory bandwidth usually does not scale up N times. Quite often, the original memory path is shared by multiple processors and performance degradation may be observed when they compete for the shared memory bandwidth.

- Many other common problems affecting the final speedup in parallel computing also apply to OpenMP, like load balancing and synchronization overhead.

- Compiler optimisation may not be as effective when invoking OpenMP. This can commonly lead to a single-threaded OpenMP program running slower than the same code compiled without an OpenMP flag (which will be fully serial).

Thread affinity

Some vendors recommend setting the processor affinity on OpenMP threads to associate them with particular processor cores.[43][44][45] This minimizes thread migration and context-switching cost among cores. It also improves the data locality and reduces the cache-coherency traffic among the cores (or processors).

Benchmarks

A variety of benchmarks has been developed to demonstrate the use of OpenMP, test its performance and evaluate correctness.

Simple examples

- OmpSCR: OpenMP Source Code Repository

Performance benchmarks include:

- NAS Parallel Benchmark

- Barcelona OpenMP Task Suite a collection of applications that allow to test OpenMP tasking implementations.

- SPEC series

- SPEC OMP 2012

- The SPEC ACCEL benchmark suite testing OpenMP 4 target offloading API

- The SPEChpc 2002 benchmark

- CORAL benchmarks

- Exascale Proxy Applications

- Rodinia focusing on accelerators.

- Problem Based Benchmark Suite

Correctness benchmarks include:

- OpenMP Validation Suite

- OpenMP Validation and Verification Testsuite

- DataRaceBench is a benchmark suite designed to systematically and quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of OpenMP data race detection tools.

- AutoParBench is a benchmark suite to evaluate compilers and tools which can automatically insert OpenMP directives.

See also

References

- "About the OpenMP ARB and". OpenMP.org. 2013-07-11. Archived from the original on 2013-08-09. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- "OpenMP Compilers & Tools". OpenMP.org. November 2019. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- Gagne, Abraham Silberschatz, Peter Baer Galvin, Greg (2012-12-17). Operating system concepts (9th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-1-118-06333-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - OpenMP Tutorial at Supercomputing 2008

- Using OpenMP – Portable Shared Memory Parallel Programming – Download Book Examples and Discuss

- Costa, J.J.; et al. (May 2006). "Running OpenMP applications efficiently on an everything-shared SDSM". Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing. 66 (5): 647–658. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2005.06.018. hdl:2117/370260.

- Basumallik, Ayon; Min, Seung-Jai; Eigenmann, Rudolf (2007). "Programming Distributed Memory Sytems Using OpenMP". 2007 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium. New York: IEEE Press. pp. 1–8. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.421.8570. doi:10.1109/IPDPS.2007.370397. ISBN 978-1-4244-0909-9. S2CID 14237507. A preprint is available on Chen Ding's home page; see especially Section 3 on Translation of OpenMP to MPI.

- Wang, Jue; Hu, ChangJun; Zhang, JiLin; Li, JianJiang (May 2010). "OpenMP compiler for distributed memory architectures". Science China Information Sciences. 53 (5): 932–944. doi:10.1007/s11432-010-0074-0. (As of 2016 the KLCoMP software described in this paper does not appear to be publicly available)

- Cluster OpenMP (a product that used to be available for Intel C++ Compiler versions 9.1 to 11.1 but was dropped in 13.0)

- Ayguade, Eduard; Copty, Nawal; Duran, Alejandro; Hoeflinger, Jay; Lin, Yuan; Massaioli, Federico; Su, Ernesto; Unnikrishnan, Priya; Zhang, Guansong (2007). A proposal for task parallelism in OpenMP (PDF). Proc. Int'l Workshop on OpenMP.

- "OpenMP Application Program Interface, Version 3.0" (PDF). openmp.org. May 2008. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- LaGrone, James; Aribuki, Ayodunni; Addison, Cody; Chapman, Barbara (2011). A Runtime Implementation of OpenMP Tasks. Proc. Int'l Workshop on OpenMP. pp. 165–178. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.221.2775. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-21487-5_13.

- "OpenMP 4.0 API Released". OpenMP.org. 2013-07-26. Archived from the original on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- "OpenMP Application Program Interface, Version 4.0" (PDF). openmp.org. July 2013. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- "OpenMP 5.2 Specification".

- "C - How to use printf() in multiple threads".

- "Tutorial – Parallel for Loops with OpenMP". 2009-07-14.

- Visual C++ Editions, Visual Studio 2005

- Visual C++ Editions, Visual Studio 2008

- Visual C++ Editions, Visual Studio 2010

- David Worthington, "Intel addresses development life cycle with Parallel Studio" Archived 2012-02-15 at the Wayback Machine, SDTimes, 26 May 2009 (accessed 28 May 2009)

- "XL C/C++ for Linux Features", (accessed 9 June 2009)

- "Oracle Technology Network for Java Developers | Oracle Technology Network | Oracle". Developers.sun.com. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- "openmp – GCC Wiki". Gcc.gnu.org. 2013-07-30. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- Kennedy, Patrick (2011-09-06). "Intel® C++ and Fortran Compilers now support the OpenMP* 3.1 Specification | Intel® Developer Zone". Software.intel.com. Retrieved 2013-08-14.

- "IBM XL C/C++ compilers features". IBM. 13 December 2018.

- "IBM XL Fortran compilers features". 13 December 2018.

- "Clang 3.7 Release Notes". llvm.org. Retrieved 2015-10-10.

- "Absoft Home Page". Retrieved 2019-02-12.

- "GCC 4.9 Release Series – Changes". www.gnu.org.

- "OpenMP* 4.0 Features in Intel Compiler 15.0". Software.intel.com. 2014-08-13. Archived from the original on 2018-11-16. Retrieved 2014-11-10.

- "GCC 6 Release Series - Changes". www.gnu.org.

- "OpenMP Compilers & Tools". openmp.org. www.openmp.org. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "OpenMP Support — Clang 12 documentation". clang.llvm.org. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- "GOMP — An OpenMP implementation for GCC - GNU Project - Free Software Foundation (FSF)". gcc.gnu.org. Archived from the original on 2021-02-27. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- "OpenMP* Support". Intel. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- Amritkar, Amit; Tafti, Danesh; Liu, Rui; Kufrin, Rick; Chapman, Barbara (2012). "OpenMP parallelism for fluid and fluid-particulate systems". Parallel Computing. 38 (9): 501. doi:10.1016/j.parco.2012.05.005.

- Amritkar, Amit; Deb, Surya; Tafti, Danesh (2014). "Efficient parallel CFD-DEM simulations using OpenMP". Journal of Computational Physics. 256: 501. Bibcode:2014JCoPh.256..501A. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2013.09.007.

- OpenMP Accelerator Support for GPUs

- Detecting and Avoiding OpenMP Race Conditions in C++

- "Alexey Kolosov, Evgeniy Ryzhkov, Andrey Karpov 32 OpenMP traps for C++ developers". Archived from the original on 2017-07-07. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- Stephen Blair-Chappell, Intel Corporation, Becoming a Parallel Programming Expert in Nine Minutes, presentation on ACCU 2010 conference

- Chen, Yurong (2007-11-15). "Multi-Core Software". Intel Technology Journal. 11 (4). doi:10.1535/itj.1104.08.

- "OMPM2001 Result". SPEC. 2008-01-28.

- "OMPM2001 Result". SPEC. 2003-04-01. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

Further reading

- Quinn Michael J, Parallel Programming in C with MPI and OpenMP McGraw-Hill Inc. 2004. ISBN 0-07-058201-7

- R. Chandra, R. Menon, L. Dagum, D. Kohr, D. Maydan, J. McDonald, Parallel Programming in OpenMP. Morgan Kaufmann, 2000. ISBN 1-55860-671-8

- R. Eigenmann (Editor), M. Voss (Editor), OpenMP Shared Memory Parallel Programming: International Workshop on OpenMP Applications and Tools, WOMPAT 2001, West Lafayette, IN, USA, July 30–31, 2001. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science). Springer 2001. ISBN 3-540-42346-X

- B. Chapman, G. Jost, R. van der Pas, D.J. Kuck (foreword), Using OpenMP: Portable Shared Memory Parallel Programming. The MIT Press (October 31, 2007). ISBN 0-262-53302-2

- Tom Deakin and Timothy G. Mattson: Programming Your GPU with OpenMP: Performance Portability for GPUs, The MIT Press,ISBN 978-0-262547536 (Nov, 7,2023).

- Parallel Processing via MPI & OpenMP, M. Firuziaan, O. Nommensen. Linux Enterprise, 10/2002

- MSDN Magazine article on OpenMP

- SC08 OpenMP Tutorial Archived 2013-03-19 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) – Hands-On Introduction to OpenMP, Mattson and Meadows, from SC08 (Austin)

- OpenMP Specifications Archived 2021-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Miguel Hermanns:Parallel Programming in Fortran 95 using OpenMP (19th, April, 2002) (PDF) (OpenMP ver.1 and ver.2)