North Irish Horse

The North Irish Horse was a yeomanry unit of the British Territorial Army raised in the northern counties of Ireland in the aftermath of the Second Boer War. Raised and patronised by the nobility from its inception to the present day, it was one of the first non-regular units to be deployed to France and the Low Countries with the British Expeditionary Force in 1914 during World War I and fought with distinction both as mounted troops and later as a cyclist regiment, achieving eighteen battle honours. The regiment was reduced to a single man in the inter war years and re-raised for World War II, when it achieved its greatest distinctions in the North African and Italian campaigns. Reduced again after the Cold War, the regiment's name still exists in B (North Irish Horse) Squadron, the Scottish and North Irish Yeomanry and 40 (North Irish Horse) Signal Squadron, part of 32 Signal Regiment.

| North Irish Horse | |

|---|---|

The badge of the North Irish Horse. | |

| Active | 1902–1946 1947–present (as a Sqdn) |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Yeomanry |

| Role | Formation Reconnaissance and Signals |

| Size | Two Squadrons |

| Part of | Royal Armoured Corps and Royal Signals |

| Garrison/HQ | Belfast |

| Nickname(s) | The Horse, The Millionaires Own |

| Motto(s) | Quis Separabit (Who shall separate us) (Latin) |

| March | Garryowen |

| Anniversaries | Hitler Line, 24 May |

| Engagements | Somme, Ypres, Hitler Line, Iraq, Afghanistan |

| Commanders | |

| Honorary Colonel | Colonel J W Rollins MBE |

| Insignia | |

| Tartan | Saffron (pipes) |

History

Background

The raising of Militia units in Ireland commenced with the "Militia Act 1793", which in Ireland was used in conjunction with the compulsory disbandment of Lord Charlemont's Irish Volunteers, who had become a political entity and "out of the scope of official influence".[1] The scope of the Militia was broadened by an act of the Dublin Parliament in 1796, which led to the raising of forty-nine troops of cavalry, later renamed yeomanry. A troop normally consisted of a captain, two lieutenants (commissioned by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland) and forty men, along with a permanent sergeant and trumpeter. Troops were grouped together under the command of a regular army brigade major. The force was known collectively as the "Irish Yeomanry". Each man provided his own horse.[2] The falling need for this force eventually led to its disbandment in 1834.[3]

With the advent of the Boer War, a parliamentary decision was taken to raise squadrons of Yeomanry Cavalry under the "Militia and Yeomanry Act 1901" for service in South Africa. Because of the pressing need to raise this force quickly, normal cavalry training with swords or lances (known as the arme blanche) was dispensed with and the new yeomanry was issued only with rifles in a break with cavalry tradition. This new force was called the Imperial Yeomanry. Six companies were quickly raised in Ireland, including the 46th (1st Belfast), 54th (2nd Belfast), 60th (North Irish), and the 45th (Dublin) (known as the Dublin Hunt Squadron) commanded by Captain the Earl of Longford. The 45th, 46th, 47th and 54th formed the 13th (Irish) Battalion Imperial Yeomanry. The 47th (Duke of Cambridge's Own) was raised from rich "men-about-town" in London by the Earl of Donoughmore and paid £130 each for their horses and equipment. The officers of the battalion included the Earl of Leitrim, Sir John Power (of the Powers whiskey family) and James Craig (later Lord Craigavon), and was known as the "Millionaires Own".[4]

Formation

Following the South African war, sixteen new yeomanry regiments were formed, two of these in Ireland. King Edward VII approved the formation of the North of Ireland Imperial Yeomanry and the South of Ireland Imperial Yeomanry in 1901. Their formation was sanctioned and gazetted on 7 January 1902.[5] Recruiting for the North of Ireland Imperial Yeomanry did not begin until 1903, with four squadrons being raised:[6]

- RHQ and A Squadron at Skegoneill Avenue in Belfast,[7]

- B Squadron in Derry/Ballymena,[8]

- C Squadron in Enniskillen

- D Squadron in Dundalk.

The first training camp was held at Blackrock Camp, Dundalk in 1903; thereafter, camps were held every third year at the Curragh and other years at Ballykinlar, Dundrum, Magilligan and Bundoran.[6]

The regiment became part of the special reserve in 1908 and its name was changed to the North Irish Horse as part of the Haldane Reforms, the formation of the Territorial Force, which created the Special Reserve of Militia and Yeomanry regiments in Ireland. The North Irish Horse, along with the other Militia battalions, remained on the Special Reserve list until 1953. This arrangement gave the Irish units precedence in the line over the Territorial Army regiments just after the Cavalry of the Line, but also guaranteed the use of the Militia and Yeomanry in overseas conflicts.[9]

The first commander was the Earl of Shaftesbury, whose adjutant was Captain RGO Bramston-Newman, 7th (Princess Royal's) Dragoon Guards, from Cork. Senior NCOs from regular Cavalry of the Line units became the permanent staff instructors (PSIs). On 7 December 1913, the Duke of Abercorn was appointed as the regiment's first honorary colonel.[10]

The First World War

The declaration of war against Germany in August 1914 found the North Irish Horse at summer camp, as was its sister regiment, the South Irish Horse. The Expeditionary Force squadron (designated A Squadron) under the command of Major Lord Cole, consisting of 6 officers and 154 other ranks, along with its counterpart in the South Irish Horse (designated B Squadron) was assigned to the British Expeditionary Force. Both squadrons sailed from Dublin on the SS Architect on 17 August 1914.[11] They were the first non-regular troops to land in France and be in action in the First World War. They were joined shortly afterwards by C Squadron of the North Irish Horse under the command of Major Lord Massereene and Ferrard DSO. Three more squadrons of the 'Horse' were to join the regiment in France landing on 2 May 1915, 17 November 1915 and 11 January 1916. A total of 70 officers and 1,931 men of the regiment went to war between 1914 and 1916.[12]

The North Irish Horse did not stay together as a unit, but squadrons were attached to different formations in the BEF as and when required:

- A Squadron – attached to GHQ until 4 January 1916, transferred to 55th (West Lancashire) Division. On 10 May 1916, along with D and E Squadrons, it was attached to VII Corps, forming the 1st North Irish Horse . Together they constituted VII Corps Cavalry Regiment. 1 NIH was transferred to XIX Corps in July 1917, and then to V Corps, September 1917. In March 1918, it was reroled as V (North Irish Horse) Corps Cyclist Battalion until the end of the war.[13]

- B Squadron – was attached to the 59th (2nd North Midland) Division, August 1915. In June 1916, it formed, along with C Squadron and the Service Squadron of the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons, the 2nd North Irish Horse. This battalion was attached to X Corps until August 1917, then disbanded. The men were sent to be trained as infantry and more than 300 of them joined the 9th (Service) (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers.[13]

- C Squadron – moved to France on 22 August 1914 and was attached to GHQ before being detached to 5th Division as the divisional cavalry squadron to replace A Sqn of the 19th Hussars. On 14 April 1915, it was transferred to the 3rd Division, and in June 1916 was sent to join B Sqn in the 2nd North Irish Horse which was later disbanded.[13]

- D Squadron – was attached to the 51st (Highland) Division in early 1915, but in June 1916 joined A Sqn in the 1st North Irish Horse.[13]

- E Squadron – was attached to 34th Division as part of the divisional mounted contingent from early 1915, and in June 1916 joined A Sqn in the 1st North Irish Horse.[13]

- F Squadron – was attached to the 33rd Division from early 1915 until April 1916, before being briefly attached to 1st Cavalry Division, 49th (West Riding) Division, and 32nd Division, before joining X Corps in June 1916. It was redesignated B Squadron 1 North Irish Horse in May 1916.[13]

On 25 May 1916, 2nd North Irish Horse was formed. This regiment included, as A Sqn, the Service Squadron of the 6th Inniskilling Dragoon Guards, which had been formed on 2 October 1914 from volunteers of the Inniskilling Horse of the Ulster Volunteer Force.[14] This squadron did not welcome the change and maintained its Inniskilling identity; being allowed to keep its precedence in the line coming just after the dragoons until 1919.[15]

Records indicate that a third regiment was being formed at the depot in Antrim and it has been speculated that this had unofficially adopted the title "3rd North Irish Horse" but no official records exist to support this.[16]

Cyclist Corps

As the war in France and the Low Countries stagnated into trench warfare, the mobility of cavalry and other mounted troops was restricted leading to many cavalry regiments being dismounted and deployed on a range of tasks from that of infantry to menial tasks, including burying the dead. The loss of some of the squadrons' war diaries for the early part of the war means that much information is no longer available, but enough remains to know that some men were deployed on fatigues, enough to render the squadrons non-existent from a "military or fighting point".[17] The historian of the British Cavalry, the Earl of Anglesey, noted that "the cavalry were being used for every odd job where there was no-one else to carry it out".[17] This led to many officers and men transferring to other arms because they felt they were not taking an active part in the war. The vast majority of "Horse" casualties in the Great War were when serving with other units during this period.[18]

After conversion to a cyclist battalion, the regiment became part of the "Great Retreat of 1918" during the Operation Michael phase of the German Kaiserschlacht (or Spring Offensive).[19] Following the Armistice, on 13 November a supply of boot blackening and button polish was made available in the other ranks canteen and the regiment began handing in stores in preparation for moving back to Ireland. The regiment's location was close to le Cateau, not far from where it had started the war.[20] During the Great War, the "Horse" won 18 battle honours, and lost 27 officers and 123 men. One officer, Captain Richard West, was awarded the Victoria Cross, Distinguished Service Order and Bar, and Military Cross.[21]

The Inter-war years

By 31 January 1919, the regiment was preparing to reduce to a cadre of three officers, five senior ranks and twenty-seven other ranks who would oversee the rundown of the regiment and its departure from France. On 13 May 1919, the rear party left Vignacourt en route for Pembroke Dock; in Antrim, the regimental depot was closed and the remaining men there were transferred to the Curragh Camp prior to being demobbed.[22] The regiment's horses were transferred to the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars and the regiment was classed as "disembodied", which in British Army parlance meant that it no longer existed except as a name on the Army List with a complement (in this case) of an Honorary Colonel, Honorary Chaplain, a Brevet Colonel (EA Maude), six majors, six subalterns and the quartermaster although these officers had no peacetime training commitments.[22]

The naming conventions changed as the commitment of the Territorial Force in Great Britain was rewarded by its renaming as the Territorial Army. The Special Reserve in Ireland was renamed "the Militia" on 1 October 1921. The Army List contained a section headed, "Cavalry Special Reserve – Irish Horse, North Irish, South Irish". In 1922, this changed to "Cavalry Militia" with precedence following the 17th/21st Lancers. By this time, however, the South Irish Horse had been disbanded on 31 July 1922, as a result of the partition of Ireland. Following the disbandment of King Edward's Horse in 1924, the North Irish Horse became the sole cavalry militia regiment on the army list and also the only militia regiment that had not been placed in suspended animation.[23]

On 28 February 1924, the regiment held its first reunion in Thompson's Restaurant in Belfast, where it was agreed that a memorial to the dead of the Great War should be commissioned. The sum of £500 was allocated and a memorial window was unveiled by the Earl of Shaftesbury and dedicated by the Right Reverend RW Hamilton MA, the Moderator of the Presbyterian Church on 25 April 1925 on the occasion of the 2nd Regimental Reunion.[24]

The "One Man Regiment"

Retirement and death eventually reduced the regimental strength in 1934 to just one combatant officer, Major Sir Ronald D Ross Bt, MC. This became a source of amusement in society and the North Irish Horse was given the sobriquet of the "One Man Regiment". This state of affairs continued until 1938, when the British Government decided to increase the number of available regiments to meet the possible threat of war from the emergent Nazi regime in Germany.[25]

Prelude to war

On 31 August 1939, the War Office ordered the reconstitution of the regiment as a wheeled armoured car unit under the command of Sir Basil Brooke (formerly 10th Hussars) with Lord Erne as his second in command, although Brooke was shortly to leave the position as his political commitments took precedence. Ultimately to be replaced, after several temporary officers, by Lt Col David Dawnay, grandson of the 8th Viscount Downe. Recruiting commenced and instructors were brought in from other RAC and Yeomanry units to raise the Horse from its "One Man Regiment" status from scratch. On 11 September, a Special Army Order transferred the regiment from the Cavalry of the Line to the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC). By November, 50 recruits had been trained and a further 30–40 were due to start training immediately. In the same month, the regiment also moved its base to Enniskillen Castle.[26] By January 1940, the regiment had received its vintage Rolls-Royce armoured cars fitted with Vickers machine guns and No 11 radio sets[27] and was able to form three sabre squadrons plus HQ Sqn. The officer cadre was again heavily filled by members of the nobility with the squadrons being commanded by:[28]

- HQ Squadron – Captain Newton commanding with the Marquess of Ely as second in command, based at Castle Barracks

- A Squadron – Captain Lord O'Neill, based at County Hall

- B Squadron – Captain Booth, based at the McArthur Hall

- C Squadron – Captain Sir Norman Stronge Bt, based at the Orange Hall

Training was interrupted on 24 May 1940 when an Irish Republican Army (IRA) bomb exploded close to the officers' mess, which was in the Main Street in Enniskillen, but before any further incidents occurred the regiment was moved to Portrush.[29]

Training exercises continued along the north coast, which caused a certain amount of boredom amongst the officers and men who by now had expected to be fighting. On 19 April 1941, the regiment moved to Abercorn Barracks at Ballykinlar and re-equipped as an armoured regiment with Mk I Valentine tanks.[30]

On 18 October 1941, the Horse left Northern Ireland and took up new accommodation at Westbury, Wiltshire with the squadrons billeted in the surrounding villages.[31] The role was changed again at this point and the regiment handed in its Valentines to receive Churchill I – Mk IV's; it was assigned to the 34th Army Tank Brigade under the command of JN Tetley, son of the English brewing magnate.[32]

Tank names

At this point, the tanks were given markings that corresponded to the formation, regiment and squadrons to which they belonged and, in a practice that was to become customary with all Irish units of the RAC, each tank was named after an Irish town or place beginning with the letter of the squadron designation:[33]

| HQ Squadron |

| A Squadron

Ardara, Aghadowey, Aghalee, Ahoghill, Aldergrove, Antrim, Ardara, Ardreagh, Ardstraw, Armoy, Ardress, Arklow, Artigavan, Augher, Aughnacloy, Annalong, Ardmore, Ards, Armagh, Ashbourne |

| B Squadron

Ballina, Ballyclare, Ballykinlar, Ballyrashane, Belfast, Blackrock, Ballybay, Ballygawley, Ballymena, Banbridge, Benburb, Boyne, Ballycastle, Ballyjamesduff, Ballymoney, Bangor, Bessbrook, Bushmills |

| C Squadron

Carnlough, Castlederg, Cavan, Clonmel, Cobh, Cookstown, Carrickfergus, Castlerobin, Claudy, Coagh, Coleraine, Cork, Carryduff, Castlerock, Clogher, Coalisland, Comber, Crossgar |

| Recce Squadron

Edenderry, Enniscorthy. Enniskillen, Edgeworthstown, Enniscrone, Ennistymon, Ennis, Enniskerry, Eyrecourt |

The regiment continued to be moved around the Home Counties and also spent time in Wales, exercising and becoming familiar with its Churchill tanks. On 6 September 1942, it was transferred from the 34th Tank Brigade to the 25th Army Tank Brigade, which was attached to the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division, joining the 51st (Leeds Rifles) Royal Tank Regiment (formerly the 7th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment)[34] and the 142nd Regiment RAC (formerly the 7th Battalion, Suffolk Regiment).[35]

As Christmas leave was drawing to a close, those still away from the unit were recalled by telegram and ordered to get ready to deploy for overseas service, although oddly, they were then given six days "embarkation leave" (with an extra day to allow the Irishmen to travel home).[36] On their return, the regiment's tanks were sheeted down so that all markings were hidden and all ranks had to divest themselves of identifying badges to prevent knowledge of their deployment becoming known. All were then entrained for Liverpool, where they embarked on the troopship Duchess of York.[37]

Tunisia

On 2 February 1943, the North Irish Horse landed in Algiers and marched 17 miles on foot to their new camp.[38]

Its first job was to create a defensive force around Le Kef. The regiment was not up to strength at this time as many of its tanks and much of its equipment had been delayed by logistical difficulties. The regiment was ordered to leave Le Kef at speed to counter the Axis Offensive – Operation Ochsenkopf in late February 1943. It made best speed with all 27 available tanks towards Béja, some 90 miles away – one of the longest "on track" journeys ever made by Churchill tanks. In the ensuing 60-hour action, mostly against elements of the German 10th Panzer Division, the Horse took its first casualties of the war and lost a number of tanks to enemy artillery and direct tank-on-tank actions. It also received its first decoration, with Captain Griffith being awarded the Military Cross.[39]

The regiment continued to support other elements of the invasion force in troop or squadron formations, taking heavy casualties and losing tanks but continuing to press forward all the time until, in early April moving to Oued Zarga where the entire regiment came together for the first time since landing at Algiers.[40] In the further advance north while attached to the 38th (Irish) Brigade, which was under the command of Brigadier Nelson Russell, the Horse showed the agility of the often underestimated Churchills by climbing heights regarded as safe from tanks and surprising the Germans occupying them, a fact noted by Spike Milligan in his account of the Tunisian Campaign in his book "Rommel?" "Gunner Who?"[41] The most notable of these feats of tank hill climbing was the attack on Djebel Rhar (also known as Longstop Hill) in support of the 5th Buffs. The German infantry did not expect tanks to be able to make the crest of the Djebel and as a result were thrown into panic when the Churchills of B Sqn appeared in their midst. On 16 June, the Belfast Telegraph carried a report of the action:

It was very slow and therefore a most impressive assault with steel. At times the tanks almost 'stood on their heads', twisting to avoid mounds of rock and to get at right angles to the huge cracks and shell holes, but always getting nearer and nearer. Like beetles trying to climb an inverted ice-cream cone, they slipped a little, hung suspended and then went onwards towards the top. The behaviour of these tanks upset the Germans. Such tactics were untanklike, and no answer was contained in their military textbooks. Too late now to shift the anti-tank guns from their positions, too late to make alternative arrangements to deal with the new menace. There was only one answer – retreat, and that's what the Germans did – leaving the British tanks and infantry in possession of the first slope up the heights of Longstop. So ended 23 April.[42]

One German prisoner was heard to remark that the tanks were "Iron Mules".[43]

On 6 May, the final attack was launched against Tunis and, after severe street fighting and the capture of six 88 mm guns by C Sqn (in support of the Indian Brigade), the town was finally occupied. This effectively ended the campaign in Tunisia.[44]

The Italian Campaign

The Horse were allowed to rest and receive replacement vehicles and men for several months after the Tunisian actions. It has been surmised that this is because General Montgomery did not believe the Churchill tank to be a practical vehicle for the Italian campaign.[45] Nevertheless, the regiment embarked on 16 April for Naples, coming under air attack as it entered the harbour two days later. Vesuvius could be seen just a few miles away with fire and smoke pouring from its brim, having erupted just several weeks earlier on 19 March.[46]

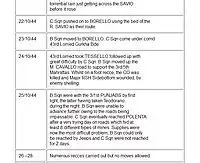

The Hitler Line

At Afragola[47] the regiment received 18 Sherman tanks and then loaded all tanks onto trains to be taken across country to Foggia and from there moved into a brigade harbour area near the village of Lucera. By now, Lord O'Neill had been given command of the regiment, with Colonel Dawnay moving on to brigade staff. After a week in harbour, the regiment was sent on tank transporters to Mignano near Monte Cassino, which had fallen some days earlier along with the rest of the Gustav Line. The fighting was not over, however, as the Adolf Hitler Line, now renamed the Senger Line, lay just six miles north, and it would be the next objective.[48] The Horse was briefed for Operation Chesterfield, which was an assault by the 1st Canadian Division supported by tanks of the North Irish Horse and the 51st Royal Tanks. H Hour was to be at 6 am on 23 May. The plan required the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigades, supported by the two tank regiments, to break through the Hitler Line on a 3,000-yard front. The assaulting troops came under a withering hail of fire on the well-prepared killing grounds of the heavily defended German positions. The Horse took heavy casualties and had to regroup by merging depleted squadrons together. One tank slipped off a track and fell 50 feet into a ravine, rolling over on its turret and then back onto its tracks. The crew were shaken but unhurt, and the incident gave them another chance to display the marvellous climbing skills of the Churchill as they crawled slowly up the almost sheer walls of the ravine to re-enter the battle. During this battle, Major Griffiths again displayed great heroism and was later awarded the only bar to the MC that an officer of the regiment received. The total cost to the Horse in the engagement was 36 men killed in action and 32 tanks lost. This represented 60% of the regimental strength.[49] The date of 23 May was later chosen as a "Regimental Day" to commemorate the bloodiest day in the history of the North Irish Horse, which lost more men than on any other day in two world wars. The breakthrough happened, however, and the German defenders began evacuating the position on the night of 23 May. Meanwhile, the allied advance continued.[50]

As a result of the breaking of the Hitler Line and in "appreciation of the support they received" the regiment was asked by the Canadians to wear the Maple Leaf insignia of the Canadian Military. In the battles of the Hitler Line was a Donegal born Lieutenant Pat Reid MC, who in later life would emigrate to Canada and would chair the committee selected by the Canadian Prime Minister that would choose the Maple Leaf design for the new national Flag of Canada.[51]

On 4 May, the regiment, along with the rest of the 25th Tank Brigade, was transferred to the 4th Division in support of the 28th Brigade, but remained in reserve. After news of the D Day Landings was heard, the regiment was again transferred and came under command of the 17th Indian Infantry Brigade. This brief period of respite allowed a number of the men to visit Rome. Many visited the Basilica San Pietro and marvelled at the undamaged splendour of such an edifice.[52]

The regiment was then tasked to put together a composite unit of Shermans to relieve the 142nd RAC Regt's composite group with the 8th Indian Infantry Division, and the advance began westwards to Perugia, which fell on 20 June. On 16 June, the Horse again relieved the 142nd, this time at Bastia Umbra.[53][54] In the days and actions that followed, new upgunned Churchill tanks arrived, with their Besa machine guns.[55]

The Gothic Line

Advancing again though mountainous countryside, another tank slid off the track and rolled six times down a 200-foot slope. The crew were not so lucky this time, as one was killed and the rest injured. The tank was a write-off.[56] The race was on, however, to drive the Germans back, and the North Irish Horse was rushed in again to relieve the hard-pressed 142nd RAC Regt at Maria del Monte. On 3 September, it crossed the Conca river,[54] followed by an attack on Coriana to secure the bridges crossing the Marano river. On 8 September, the regiment was withdrawn to a safer area in the knowledge that the Gothic Line had been broken.[54]

On 29 November, the regiment was advancing north to Monte Cavallo supporting the Mahratta infantry. Lt Col Lord O'Neill arrived and took up a position of observation at a small stone barn. A heavy shell impacted nearby and he was killed.[57]

By this time, the autumn rains had arrived, which slowed the Allied advance but did not stop it. On 2 October, the regiment was ordered to move to Poggio Berni to relieve the 6th Royal Tank Regiment. Action continued until 3 November, when the Horse were pulled out of the line and local leave granted after a memorial service for those killed in action.[58]

The end of the Italian Campaign

On 7 November, Lt Col Llewellen-Parker took command, and the advance northwards quickly continued. The Churchills once again proved their worth in their ability to cross natural obstacles such as rivers, mountains and the thick glutinous mud, which formed on the arable farmland during the rains and after it had been churned up by thousands of men and machines. Eventually, the regiment was granted an extended period of maintenance and rest at Riccione. On 4 December, it was again transferred, this time to the 21st Tank Brigade under the command of Brigadier David Dawnay, the former regimental commander. On 12 January, it moved into Ravenna in support of the Italian Gruppo Cremona,[59] which was now fighting on the side of the allies.[60]

In late March, the regiment was involved in the action south of the Senio river and by 2 April was facing the enemy's defences along the flood-banks and engaging them at close range. The last of the German resistance crumbled as more tanks made it into position to engage them, and they surrendered, with the Horse taking 40 prisoners.[61]

Following Operation Buckland[62] and the crossing of the River Po, the regiment was ordered to stand down on 30 April 1945 for the last time in the Second World War. Two days later, all German forces in Italy surrendered.[63]

The North Irish Horse lost 73 men killed in action during the Second World War, including a commanding officer, two squadron leaders and several troop leaders.[64]

Post war

In the immediate aftermath of the German surrender, the regiment fell into a routine of guard duties and time off. Eventually, most of the tanks were handed in except for three per squadron, and a move was made into Austria, where the Horse took on the role of armoured reconnaissance regiment for the 78th Division. In January 1946, another move was effected into Germany, where the Horsemen carried out internal security duties in the Wuppertal area until 7 June, when these duties were handed over to the 14th/20th Hussars and the North Irish Horse was disbanded.[65]

In 1947, however, it was reformed as part of the extension of the Territorial Army Yeomanry into Northern Ireland. In 1956, the TA lost its tanks, and the Horse became an armoured reconnaissance regiment, again in armoured cars. It avoided disbandment at this point and did so again in 1961.[6]

Further cuts to the TA in 1967 saw the Horse disbanded and re-established as D Squadron The Royal Yeomanry. In 1969, 'B' Squadron in Derry was re-badged as 69 (NIH) Signal Squadron and became part of 32nd (Scottish) Signal Regiment.[66]

During Options for Change in 1992, the Horse was re-established as an independent Reconnaissance Squadron, equipped with Land Rovers and working under the command of the Royal Irish Rangers. The signal squadron survived and became part of 40th (Ulster) Signal Regiment. In 1999, the no-longer independent North Irish Horse joined an expanded Queen's Own Yeomanry as B Squadron.[66] The Land Rovers were replaced by Spartan armoured personnel carriers as B Sqn took on the role of providing support troopers. During the post-1956 period, the regiment was equipped with a variety of armoured vehicles such as Spartan APCs.[6]

The unit's name survives in the modern Army Reserve as B (North Irish Horse) Squadron, Queen's Own Yeomanry – a squadron equipped with CVR(T) Scimitar and Spartan based at Dunmore Park Camp, Antrim Road, Belfast, with RHQ in Newcastle upon Tyne.[67] Personnel have been deployed to Kosovo, Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan.[67]

On 22 October 2009, in the early morning, a device was thrown over the front gate of Dunmore Park Camp in Ashfield Crescent. It was suspected that dissident republicans carried out the attack.[68]

Under the Army 2020 re-organisation B (North Irish Horse) Squadron came under command of the Scottish and North Irish Yeomanry, while 69 (North Irish Horse) Signal Squadron became 40 (North Irish Horse) Signal Squadron, part of 32 Signal Regiment.[69]

Sponsorship

Every yeomanry regiment has a regular regiment to sponsor it and supply it with a series of permanent staff instructors (PSIs). In the case of the North Irish Horse, it had been the 1st King's Dragoon Guards from the outset, but these ties were broken in 1958 when the KDG amalgamated with the 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays) to form the 1st The Queen's Dragoon Guards. From that point onwards, sponsorship was given by two of the remaining cavalry regiments of the time, which were the 5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards and the Queen's Royal Irish Hussars, both of whom had also had to endure amalgamation in past reforms.[70]

Guidon & Memorial

On 15 May 1960, the regiment was presented its guidon by Princess Alexandra of Kent at a parade held on the Balmoral Showgrounds in Belfast. On 28 October 1962, a second memorial window was unveiled in Belfast City Hall to commemorate the fallen of the 2nd World War. This was placed beside the World War I window. It was unveiled by General Dawnay and dedicated by the Archdeacon of Raphoe, the Reverend Louis Crooks (Regimental Chaplain), who himself was a veteran of World War II with the 9th (Londonderry) HAA Regiment.[71]

Uniform

The unusual review order uniform worn by the regiment prior to the First World War included a wide brimmed black felt hat with a long flowing black plume of cocks feathers. This headdress was modeled on that of the Italian Bersaglieri and was unique in the British Empire. A dark green "lancer" style tunic was worn with white facings and chain mail epaulettes, together with dark blue "overalls" (tight fitting cavalry breeches) with white stripes.[72]

Battle honours

Further battle honours were awarded to the Horse for its distinguished service in a number of actions from 1943 to 1945. Those in bold type are emblazoned on the regimental guidon.[66]

| 1914–1918 | 1939–1945 |

|---|---|

| RETREAT FROM MONS, MARNE 1914, AISNE 1914, ARMENTIERS 1914, Somme 1916/18, ALBERT 1916, MESSINES 1917, Ypres 1917, Pilckem, St Quentin, BAPAUME 1918, Hindenburg Line, Epehy, St Quentin Canal, CAMBRAI 1918, SELLE, Sambre, FRANCE AND FLANDERS | HUNT'S GAP, Sedjenne, Tamera, Mergueb Chaouach, DJEBEL RMEL, LONGSTOP HILL, 1943, TUNIS, North Africa 1943, Liri Valley, HITLER LINE, ADVANCE TO FLORENCE, GOTHIC LINE, Monte Farneto, Monte Cavallo, CASA FORTIS, Casa Bettini, Lamone Crossing, Valli di Comacchio, SENIO, ITALY 1944–45 |

Attached to

- 34th Army Tank Brigade — 1 December 1941 – 3 September 1942

- 25th Army Tank Brigade — 3 September 1942 – 3 December 1944

- 21st Tank Brigade — 4 December 1944 – 10 June 1945

- 21st Armoured Brigade — 11 June 1945 – 31 August 1945

Notable personalities

- Category:North Irish Horse officers

- Captain Sir Basil Brooke Bt., KG, CBE, MC, PC, HML

- Captain Richard Annesley West VC, DSO & Bar, MC

- Thomas Pakenham, 5th Earl of Longford

- Major The Earl of Erne

- Major The Lord Cole

- Major The Lord Loftus

- Robert Grosvenor, 5th Duke of Westminster

- Gerald Grosvenor, 6th Duke of Westminster

- James Craig, 2nd Viscount Craigavon

- Charles Clements, 5th Earl of Leitrim

- Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 9th Earl of Shaftesbury

- James Hamilton, 3rd Duke of Abercorn

- Colonel Sir Michael McCorkell

- Major Lord Massereene & Ferrard

- Sir Ronald Ross, 2nd Baronet

- Viscount Downe

- Shane Edward Robert O'Neill, 3rd Baron O'Neill

- Sir Norman Stronge

References

- Doherty p1

- Doherty p2

- "IRISH YEOMANRY Coups". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 20 June 1843. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Doherty p4

- "No. 27395". The London Gazette. 7 January 1902. p. 151.

- "The History of the North Irish Horse" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Tardif, p. 2

- Doherty p10

- Doherty p11

- Doherty p9

- Hughes, Gavin (2015). Fighting Irish: The Irish Regiments in the First World War. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-1785370229.

- Doherty p16

- Chris Baker (1996–2008). "The North Irish Horse—Regiments of the Special Reserve—North Irish Horse". The long, long trail. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- Philip Tardif (2008). "North Irish Horse in the Great War—A brief history". Notorious strumpets. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- Doherty p35

- Doherty p23

- Doherty p22

- Doherty p25

- Doherty p26

- Doherty p34

- "Casualty details—West, Richard Annesley". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- Doherty p38

- Doherty p38-39

- Doherty p39

- Doherty p40

- Doherty p45

- "Wireless Set No. 11". Royal Signals Museum. Archived from the original on 4 October 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- "War Diaries For North Irish Horse: 1939". warlinks.com. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "War Diaries For North Irish Horse: 1940". warlinks.com. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "War Diaries For North Irish Horse: 1941". warlinks.com. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Doherty p50

- "THE HISTORY of 34 ARMOURED BRIGADE". Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- "Churchill Tank list". Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "Leeds Rifles". Yorkshirevolunteers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2005. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- 142 RAC War Diary, January–December 1942, TNA file WO 166/6937.

- Doherty p57

- "War Diaries For North Irish Horse: 1943". warlinks.com. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Doherty p60

- Doherty p80

- Doherty p80-96

- "Rommel?": "Gunner Who?" Spike Milligan ISBN 978-0-14-004107-1

- Doherty p105-106

- Doherty P108

- Stevens, Major-General W. G. "The Campaign Ends". NZETC. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Doherty p125

- "History and eruptions". Vesuvioinrete.it. 6 January 1944. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Robert Cull. "War Diaries of The North Irish Horse". Warlinks.com. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Doherty p 130

- Doherty p142

- Doherty p147

- "Celtic Connection".

- Doherty p 148

- "Upper Tiber Valley". Assisi War Cemetery. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- "War Diaries For North Irish Horse: 1944". warlinks.com. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- "BESA (Gun, Machine, 7.92mm, BESA) Vehicle / Tank Machine Gun". Military Factory. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Doherty p173

- Doherty p205

- Doherty p207

- O'Reilly p159

- "Italy". Worldwar2history.info. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Doherty 227

- Eighth Army. "Eighth Army Boundaries and Plan for Operation BUCKLAND". NZETC. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Blaxland, p277

- Doherty p232

- Doherty p236

- "North Irish Horse". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "B Squadron, North Irish Horse". Archived from the original on 29 June 2006.

- "TA explosion 'could have killed'". BBC News. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- "40th Signal Regiment, Royal Corps of Signals". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 18 April 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "The Queen's Royal Hussars Association". Qrh.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 October 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Doherty p239

- Smith, R.J. (December 1987). The Uniforms of the British Yeomanry Force 1794–1914 10: The Yeomanry Force at the 1911 Coronation. p. 29. ISBN 0-948251-26-3.

Bibliography

- Blaxland, Gregory (1979). Alexander's Generals (the Italian Campaign 1944–1945). London: William Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0386-5.

- Doherty, Richard (2002). The North Irish Horse, A Hundred Years of Service. Spellmount. ISBN 978-1862271906.

- O'Reilly, Charles T. (2001). Forgotten Battles. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0195-7.

- Tardif, Phillip (2015). The North Irish Horse in the Great War. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1473833753.

External links

- "North Irish Horse". Orders of Battle.com.

- "North Irish Horse". Official – North Irish Horse Regimental Association and Benevolent Fund.

- "North Irish Horse". WW2 NIH Veteran Gerry Chester's Website.