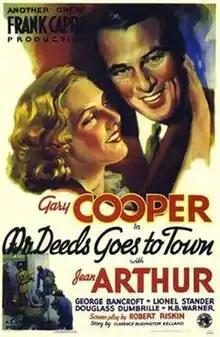

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town is a 1936 American comedy-drama romance film directed by Frank Capra and starring Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur in her first featured role. Based on the 1935 short story "Opera Hat" by Clarence Budington Kelland, which appeared in serial form in The American Magazine, the screenplay was written by Robert Riskin in his fifth collaboration with Frank Capra.[2][3]

| Mr. Deeds Goes to Town | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Frank Capra |

| Screenplay by | Robert Riskin |

| Based on | Opera Hat 1935 story in American Magazine by Clarence Budington Kelland |

| Produced by | Frank Capra |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph Walker, a.s.c. |

| Edited by | Gene Havlick |

| Music by | Howard Jackson (musical director) |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $845,710 or $500,000[1] |

| Box office | $2.5 million (rentals)[1] |

Plot

During the Great Depression, Longfellow Deeds, the co-owner of a tallow works, part-time greeting card poet, and tuba-playing inhabitant of the hamlet of Mandrake Falls, Vermont, inherits 20 million dollars from his late uncle, Martin Semple. Semple's scheming attorney, John Cedar, locates Deeds and takes him to New York City. Cedar gives his cynical troubleshooter, ex-newspaperman Cornelius Cobb, the task of keeping reporters away from Deeds.

Cobb is outfoxed by star reporter Louise "Babe" Bennett, who appeals to Deeds' romantic fantasy of rescuing a damsel in distress by masquerading as a poor worker named Mary Dawson. She pretends to faint from exhaustion after "walking all day to find a job" and worms her way into his confidence. Bennett proceeds to write a series of enormously popular articles on Longfellow, portraying him as a yokel who has suddenly inherited riches, and giving him the nickname "Cinderella Man".

Cedar tries to get Deeds' power of attorney in order to keep his own financial misdeeds secret. Deeds, however, proves to be a shrewd judge of character, easily fending off Cedar and other greedy opportunists. He wins Cobb's wholehearted respect and eventually Babe's love. She quits her job in shame, but before she can tell Deeds the truth about herself, Cobb finds it out and tells Deeds. Deeds is left heartbroken and decides to return to Mandrake Falls.

After he has packed and is about to leave, a dispossessed farmer stomps into his mansion and threatens him with a gun. He expresses his scorn for the seemingly heartless, ultra-rich man, who will not lift a finger to help the multitudes of desperate poor. After the intruder comes to his senses, Deeds realizes what he can do with his troublesome fortune. He decides to provide fully equipped 10-acre (4-hectare) farms free to thousands of homeless families if they will work the land for three years.

Cedar joins forces with Deeds' only other relative, Semple, and his domineering wife, in an attempt to have Deeds declared mentally incompetent. A sanity hearing is scheduled to determine who should control the fortune. During the hearing, Cedar calls an expert who diagnoses Deeds with manic depression based on Babe's articles and witnesses to his recent behavior. Though Deeds has pledged to defend himself, he refuses to speak.

Babe speaks up passionately on his behalf, castigating herself for what she did to him. When he realizes that she truly loves him, he begins speaking, systematically punching holes in Cedar's case and then landing one in his face. The judge declares him to be not only sane, but "the sanest man who ever walked into this courtroom". Victorious, Deeds and Babe kiss.

Cast

- Gary Cooper as Longfellow Deeds

- Jean Arthur as Babe Bennett

- George Bancroft as MacWade

- Lionel Stander as Cornelius Cobb

- Douglass Dumbrille as John Cedar

- Raymond Walburn as Walter

- H. B. Warner as Judge May

- Ruth Donnelly as Mabel Dawson

- Walter Catlett as Morrow

- John Wray as Farmer

Uncredited:

- Margaret Seddon as Jane

- Margaret McWade as Amy

- Gustav von Seyffertitz as Doctor Emile von Haller

- Emma Dunn as Mrs. Meredith, Deeds' housekeeper

- Charles Lane as Hallor, crook lawyer

- Jameson Thomas as Mr. Semple

- Mayo Methot as Mrs. Semple

- Gladden James as Court Clerk

- Paul Hurst as 1st Deputy

- Warren Hymer as bodyguard

- Franklin Pangborn as the tailor

Production

.Jpg.webp)

Originally, Frank Capra intended to make Lost Horizon after Broadway Bill (1934), but lead actor Ronald Colman could not get out of his other filming commitments. Thus, Capra began adapting Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. As production began, the two lead actors were cast: Gary Cooper as Longfellow Deeds and Jean Arthur as Louise "Babe" Bennett/Mary Dawson. Cooper was Capra's "first, last and only choice" for the pivotal role of the eccentric Longfellow Deeds.[4]

Arthur was not the first choice for the role, but Carole Lombard, the original female lead, quit the film just three days before principal photography, in favor of a starring role in My Man Godfrey.[5] The first scenes shot on the Fox Studios' New England street lot were in place before Capra found his replacement heroine in a rush screening.[6] The opening sequences had to be reshot when Capra decided against the broad comedy approach that had originally been written.[5]

Despite his penchant for coming in "under budget", Capra spent an additional five shooting days in multiple takes, testing angles and "new" perspectives, treating the production as a type of workshop exercise. Due to the increased shooting schedule, the film came in at $38,936 more than the Columbia budget for a total of $806,774.[7] Throughout pre-production and early principal photography, the project still retained Kelland's original title, Opera Hat, although Capra tried out some other titles including A Gentleman Goes to Town and Cinderella Man before settling on a name that was the winning entry in a contest held by the Columbia Pictures publicity department.[8]

Reception

The film was generally treated as likable fare by critics and audiences alike. Novelist Graham Greene, then also a film critic, was effusive that this was Capra's finest film to date, describing Capra's treatment as "a kinship with his audience, a sense of common life, a morality".[9] Variety noted "a sometimes too thin structure [that] the players and director Frank Capra have contrived to convert ... into fairly sturdy substance".[10]

This was the first Capra film to be released separately to exhibitors and not "bundled" with other Columbia features. On paper, it was his biggest hit, easily surpassing It Happened One Night.[11]

It was the 7th most popular film at the British box office in 1935–36.[12]

Awards and honors

| Year | Award ceremony | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | Academy Awards[13] | Best Picture | Columbia | Nominated |

| Best Director | Frank Capra | Won | ||

| Best Actor | Gary Cooper | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Story | Robert Riskin | Nominated | ||

| Best Sound Recording | John P. Livadary | Nominated | ||

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards[14] | Best Film | Mr. Deeds Goes to Town | Won | |

| Best Actor | Gary Cooper | Nominated | ||

| 1936 | National Board of Review Awards | Best Film | Mr. Deeds Goes to Town | Won |

| Top Ten Films | Mr. Deeds Goes to Town | Won | ||

| Venice Film Festival | Mussolini Cup for Best Foreign Film | Mr. Deeds Goes to Town | Nominated | |

| Special Recommendation | Frank Capra | Won | ||

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 1998: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Nominated[15]

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #70[16]

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated[17]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- Judge May: "But, in the opinion of the court, you are not only sane but you're the sanest man that ever walked into this courtroom." – Nominated[18]

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – #83[19]

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated[20]

Adaptations

A radio adaptation of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town was originally broadcast on February 1, 1937 on Lux Radio Theater. In that broadcast, Gary Cooper, Jean Arthur and Lionel Stander reprised their roles from the 1936 film.[21]

A planned sequel, titled Mr. Deeds Goes to Washington, eventually became Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). Although the latter's screenplay was actually based on an unpublished story, The Gentleman from Montana,[22] the film was, indeed, meant to be a sequel to Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, with Gary Cooper reprising his role as Longfellow Deeds.[N 1] Because Cooper was unavailable, Capra then "saw it immediately as a vehicle for Jimmy Stewart and Jean Arthur",[24] and Stewart was borrowed from MGM.[23]

The second animated feature film from Fleischer Studios, Mr. Bug Goes to Town.

A short-lived ABC television series of the same name ran from 1969 to 1970, starring Monte Markham as Longfellow Deeds.

Mr. Deeds Goes to Town was loosely remade as Mr. Deeds in 2002, starring Adam Sandler and Winona Ryder.

The Bengali movie Raja-Saja (1960) starring Uttam Kumar, Sabitri Chatterjee, and Tarun Kumar, and directed by Bikash Roy was a Bengali adaptation of this film.

The 1994 comedy The Hudsucker Proxy had several plot elements borrowed from this film.[25]

A Japanese manga adaption of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town was made in 2010 by Ogata Hiromi called Bara no Souzokunin.

The 1949 Tamil movie Nallathambi starring N S Krishnan was an adaptation of this film aimed at promoting social justice and education.

Digital restoration

In 2013 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town was slated for 4K-digital restoration and re-release.[26]

Popular culture

The bucolic Vermont town of Mandrake Falls, home of Longfellow Deeds, is now considered an archetype of small town America with Kelland creating a type of "cracker-barrel" view of rural values contrasted with that of sophisticated "city folk".[27][28] The word pixilated, previously limited to New England (and attested there since 1848), "had a nationwide vogue in 1936" thanks to its prominent use in the film,[29] although its use in the screenplay may not be an accurate interpretation.[N 2]

The word doodle, in its modern specific sense of drawing on paper rather than in its older more general sense of 'fooling around', may also owe its origin – or at least its entry into common usage – to the final courtroom scene in this film. The Longfellow Deeds character, addressing the judge, explains the concept of a doodler – which the judge has not heard before – as being "a word we made up back home to describe someone who makes foolish designs on paper while they're thinking."

The lyrics to the 1977 Rush song "Cinderella Man" on the A Farewell to Kings album are based on the story of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

In the movie Baby Boom, a babysitter refers to her hometown of Mandrake Falls.

References

Notes

- Author Lewis Foster later testified during a lawsuit that he had written the story specifically with Gary Cooper in mind.[23]

- A correspondent to Notes and Queries in 1937 objected to the screenplay's use of "pixilated" to mean "crazy" because the more correct meaning of "a 'pixilated' man" is "one whose whimseys [sic] are not understood by practical-minded people." Quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (1989), s.v. "Pixilated".

Citations

- "Wall St. Researchers' Cheery Tone". Variety. November 7, 1962. p. 7.

- Poague 1975, p. 17.

- McBride 1992, pp. 332

- McBride 1992, p. 342.

- Scherle and Levy 1977, p. 137.

- Capra 1971, p. 184.

- McBride 1992, p. 346.

- McBride 1992, p. 328.

- Greene, Graham. "Mr. Deeds". The Spectator, August 28, 1936.

- "Mr. Deeds Goes to Town". Variety. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- McBride 1992, p. 348.

- "The Film Business in the United States and Britain during the 1930s" by John Sedgwick and Michael Pokorny, The Economic History ReviewNew Series, Vol. 58, No. 1 (February 2005), pp.97

- "The 9th Academy Awards (1937) Nominees and Winners."oscars.org. Retrieved: 9 August 2011.

- McBride 1992, p. 349.

- "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies Nominees." American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 20, 2016.

- {"AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs." American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 20, 2016.

- title=AFI's 100 Years... 100 Passions Nominees." American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 20, 2016.]

- "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes Nominees." American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 20, 2016.

- "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers." American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 20, 2016.

- "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies Nominees (10th Anniversary Edition)."American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 20, 2016.

- Haendiges, Jerry. "Jerry Haendiges Vintage Radio Logs - Lux Radio Theater". Archived 2016-12-05 at the Wayback Machine otrsite.com. Retrieved: October 18, 2009.

- Capra 1971, p. 254.

- "Notes". TCM. Retrieved: June 26, 2009.

- Sennett 1989, p. 173.

- Schweinitz 2011, p. 268.

- "Capra's classic 'It Happened One Night' restored in 4K". Randi Altman's PostPerspective. Retrieved: September 3, 2018.

- McBride 1992, p. 333.

- Levy, Emanuel. "Political Ideology in Capra's Mr. Deeds Goes to Town." emanuellevy.com, April 1, 2006. Retrieved: February 26, 2008.

- Eckstorm, Fannie Hardy. "Pixilated, a Marblehead Word", American Speech, Vol. 16, no. 1, February 1941, pp. 78–80.

Bibliography

- Capra, Frank. Frank Capra: The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1971, ISBN 0-306-80771-8.

- McBride, Joseph. Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. New York: Touchstone Books, 1992, ISBN 0-671-79788-3.

- Michael, Paul, ed. The Great Movie Book: A Comprehensive Illustrated Reference Guide to the Best-loved Films of the Sound Era. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1980. ISBN 0-13-363663-1.

- Poague, Leland. The Cinema of Frank Capra: An Approach to Film Comedy. London: A.S. Barnes and Company Ltd., 1975, ISBN 0-498-01506-8.

- Scherle, Victor and William Levy. The Films of Frank Capra. Secaucus, New Jersey: The Citadel Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8065-0430-7.

- Schweinitz, Jorg (Translated by Laura Schleussner). "Enjoying the stereotype and intense double-play acting". Film and Stereotype: A Challenge for Cinema and Theory (E-book). New York: Columbia Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0-231-52521-3.

External links

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at the TCM Movie Database

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at IMDb

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at AllMovie

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at Rotten Tomatoes

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at Virtual History

- Six Screen Plays by Robert Riskin, Edited and Introduced by Pat McGilligan, Berkeley: University of California Press, c1997 1997 - Free Online - UC Press E-Books Collection

Streaming audio

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at Lux Radio Theater: February 1, 1937

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town at The Campbell Playhouse: February 11, 1940