Monsieur Verdoux

Monsieur Verdoux is a 1947 American black comedy film directed by and starring Charlie Chaplin, who plays a bigamist wife killer inspired by serial killer Henri Désiré Landru. The supporting cast includes Martha Raye, William Frawley, and Marilyn Nash.

| Monsieur Verdoux | |

|---|---|

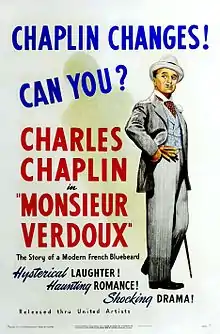

Theatrical release poster (1947) | |

| Directed by | Charlie Chaplin |

| Screenplay by | Charlie Chaplin |

| Story by | Orson Welles |

| Produced by | Charlie Chaplin |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Roland Totheroh Curt Courant (uncredited) |

| Edited by | Willard Nico |

| Music by | Charlie Chaplin |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $323,000 (US) $1.5 million (international)[2] |

Plot

Henri Verdoux had been a bank teller for thirty years before being laid off. To support his wheelchair-using wife and his child, he turns to the business of marrying and murdering wealthy widows. The Couvais family becomes suspicious when Thelma Couvais withdraws all her money and disappears two weeks after marrying a man named "Varnay", whom they only know through a photograph.

As Verdoux (Chaplin) prepares to sell Thelma Couvais's home, the widowed Marie Grosnay (Isobel Elsom) visits. Verdoux sees her as another "business" opportunity and attempts to charm her, but she refuses. Over the following weeks, Verdoux has a flower girl (Barbara Slater) repeatedly send Grosnay flowers. In need of money to invest, Verdoux, as M. Floray, visits Lydia Floray (Margaret Hoffman) and convinces her he is her absent husband. She complains that his engineering job has kept him away too long. That night, Verdoux murders her for her money.

At a dinner party with his real wife and their friend the local chemist, Verdoux asks the chemist about the drug he developed to exterminate animals painlessly. The chemist explains the formula and that he had to stop working on it after the local pharmaceutical board banned it, so Verdoux attempts to recreate the drug.

Shortly thereafter, Verdoux finds The Girl (Marilyn Nash) taking shelter from the rain in a doorway and takes her in. When he finds she was just released from prison and has nowhere to go, he prepares dinner for her with wine laced with his newly developed poison. Before drinking the wine, she thanks him for his kindness, and starts to talk about her husband who died while she was in jail. After she says her husband was a helpless invalid and that made her all the more devoted to him, Verdoux says he thinks there's cork in her wine and replaces it with a glass of unpoisoned wine. She leaves without knowing of his cynical intentions.

Verdoux makes several attempts to murder Annabella Bonheur (Martha Raye), who believes Verdoux to be Bonheur, a sea captain who is frequently away, including by strangulation while boating, and by poisoned wine, but she is impervious, repeatedly escaping death without even realizing while, at the same time, putting Verdoux himself in danger or near death. Meanwhile, Grosnay eventually softens and relents from the continual flowers from Verdoux and invites him to her residence. He convinces her to marry him, and Grosnay's friends hold a large public wedding to Verdoux's disapproval. Unexpectedly, Annabella Bonheur shows up to the wedding. Panicking, Verdoux fakes a cramp to avoid being seen and eventually deserts the wedding.

In the years leading up to the Second World War, European markets collapse, with the subsequent bank failures causing Verdoux to go bankrupt. The economic crisis leads to rise of fascism across Europe. A few years later, in 1937, with the Spanish Civil War underway, The Girl, now well-dressed and chic, once again finds Verdoux on a street corner in Paris. She invites him to an elegant dinner at a high-end restaurant as a gesture of gratitude for his actions earlier. The girl has married a wealthy munitions executive she does not love to be well-off. Verdoux reveals that he has lost his family. At the restaurant, members of the Couvais family recognize Verdoux and attempt a pursuit. Verdoux delays them long enough to bid the unnamed girl farewell before letting himself be captured by the investigators.

Verdoux is exposed and convicted of murder. When he is sentenced in the courtroom, rather than expressing remorse he takes the opportunity to say that the world encourages mass killers, and that compared to the makers of modern weapons he is but an amateur. Later, before being led from his cell to the guillotine, a journalist asks him for a story with a moral, but he answers evasively, dismissing his killing of a few, for which he has been condemned, as not worse than the killing of many in war, for which others are honored, "Wars, conflict - it's all business. One murder makes a villain; millions, a hero. Numbers sanctify, my good fellow!" His last visitor before being taken to be executed is a priest (Fritz Leiber). When guards come to take him to the guillotine he is offered a cigarette, which he refuses, and a glass of rum, which he also refuses before changing his mind. He says "I've never tasted rum", downs the glass, and the priest begins reciting a prayer in Latin as the guards lead him away and the film ends.

Cast

|

|

Production

Fellow American actor-writer-director Orson Welles received a 'story by' credit in the film. Chaplin and Welles disagreed on the exact circumstances that led to the film's production, although both men agreed that Welles initially approached Chaplin with the idea of having Chaplin star in a film as either a character based on Henri Landru or Landru himself. However, from there, both men's stories diverge considerably.

Welles claimed that he was developing a film of his own and was inspired to cast Chaplin as a character based on Landru. Chaplin initially agreed, but he later backed out at the last minute, not wanting to act for another director. Chaplin later offered to buy the script from him, and as Welles was in desperate need of money, he signed away all rights to Chaplin. According to Welles, Chaplin then rewrote several major sections, including the ending; the only specific scene to which Welles laid claim was the opening. Welles acknowledged that Chaplin claimed to have no memory of receiving a script from Welles, and believed Chaplin was telling the truth when he said this.[3]

Chaplin claimed that Welles came to his house with the idea of doing a "series of documentaries, one to be on the celebrated French murderer, Bluebeard Landru", which he thought would be a wonderful dramatic part for Chaplin. Chaplin was initially interested, as it would provide him with an opportunity for a more dramatic role, as well as saving him the trouble of having to write the film himself. However, Chaplin claimed that Welles then explained that the script had not yet been written and he wanted Chaplin's help to do so. As a result, Chaplin dropped out of Welles's project. Very shortly thereafter, the idea struck Chaplin that Landru's story would make a good comedy. Chaplin then telephoned Welles and told him that, while his new idea had nothing to do with Welles's proposed documentary or with Landru, he was willing to pay Welles $5,000 in order to "clear everything". After negotiations, Welles accepted on the terms that he would receive a "story by" screen credit. Chaplin later stated that he would have insisted on no screen credit at all had he known that Welles would eventually try to take credit for the idea.[4]

Reception

This was the first feature film in which Chaplin's character bore no resemblance to his famous "Tramp" character (The Great Dictator did not feature the Tramp, but his "Jewish barber" bore some similarity). While immediately after the end of World War II there appeared on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean a spate of films, including in 1946 The Best Years of Our Lives, It's a Wonderful Life and A Matter of Life and Death, which drew on so many people's experience of loss of loved ones and offered a kind of consolation,[5] Monsieur Verdoux had an unapologetically dark tone, featuring as its protagonist a murderer who feels justified in committing his crimes. Consequently, it was poorly received in America when it first premiered. Moreover, Chaplin's popularity and public image had been irrevocably damaged by many scandals and political controversies before its release.[6]

Chaplin was subjected to unusually hostile treatment by the press while promoting the opening of the film, and some boycotts took place during its short run. In New Jersey, the film was picketed by members of the Catholic War Veterans, who carried placards calling for Chaplin to be deported. In Denver, similar protests against the film by the American Legion managed to prevent it being shown.[7] A censorship board in Memphis, Tennessee, banned Monsieur Verdoux outright.[8] At one press conference to promote the film, Chaplin invited questions from the press with the words "Proceed with the butchering".[9] Richard Coe in The Washington Post lauded Monsieur Verdoux, calling it "a bold, brilliant and bitterly amusing film".[10] James Agee praised the film as well, calling it "a great poem" and "one of the few indispensable works of our time".[11] Evelyn Waugh praised Monsieur Verdoux as "a startling and mature work of art", although Waugh also added that he thought "there is a 'message' and I think, a deplorable one" in the film.[12]

The film was popular in France, where it had admissions of 2,605,679.[13] In 1948, a Parisian named Verdoux and employed in a bank brought an unsuccessful suit against Chaplin, alleging that his coworkers had mocked him for his name during the period of the film’s advertisement.[14]

Despite its poor commercial performance, the film was nominated for the 1947 Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay. It also won the National Board of Review award for Best Film[15] and the Bodil Award for Best American Film. In the decades since its release, Monsieur Verdoux has become more highly regarded.[6] The Village Voice ranked Monsieur Verdoux at No. 112 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[16] The film was voted at No. 63 on the list of "100 Greatest Films" by the French magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 2008.[17]

References

- Variety Staff (October 14, 2011). "Actress Marilyn Nash dies. Starred with Chaplin in 'Monsieur Verdoux'". Variety. Archived from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- Balio, Tina (2009) [1987]. United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 54, 214. ISBN 978-0-299-23004-3.

- Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter (1992). This is Orson Welles. New York City: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0-06-092439-X.

- Chaplin, Charlie (1964). My Autobiography. New York City: Simon & Schuster. pp. 415–416, 418–419. ISBN 978-1-61219-193-5.

- Srampickal, Jacob; Mazza, Giuseppe; Baugh, Lloyd, eds. (2006). Cross Connections. Rome: Gregorian Biblical BookShop. p. 199. ISBN 978-8-878-39061-4.

- Peary, Danny (2014). "Monsieur Verdoux". Cult Crime Movies. Discover the 35 Best Dark, Dangerous, Thrilling, and Noir Cinema Classics. New York City: Workman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-76118433-1.

- Caute, David (1978). The Great Fear: The Anti-Communist Purge Under Truman & Eisenhower. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 516. ISBN 0-671-22682-7.

- "Charles Chaplin in 'Monsieur Verdoux' Returns for First Time Since '47". The New York Times. July 4, 1964. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- Alvarez, Olivia Flores (October 9, 2008). "Monsieur Verdoux". Houston Press. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- Maland, Charles J. (1991). Chaplin and American Culture: The Evolution of a Star Image. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780691028606.

- Agee, James (2005). Film Writing and Selected Journalism. New York City: Library of America. pp. 293–303. ISBN 9781931082822.

- Davis, Robert Murray (1986). Evelyn Waugh, Writer. Cleveland, Ohio: Pilgrim Books. p. 213. ISBN 0937664006.

- French box office of 1948, BoxOfficeStory.com; accessed November 17, 2017.

- "Fâcheuse Homonymie : M. Verdoux fait un procès à Charlie Chaplin". Charlie Chaplin Archive. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- "Best Film Archives – National Board of Review". National Board of Review. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- "Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on August 26, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- Heron, Ambrose (November 23, 2008). "Cahiers du cinéma's 100 Greatest Films". FILMdetail.

External links

- Monsieur Verdoux at the TCM Movie Database

- Monsieur Verdoux at IMDb

- Monsieur Verdoux at AllMovie

- Monsieur Verdoux at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Monsieur Verdoux at Rotten Tomatoes

- DVD Journal article by Mark Bourne

- Monsieur Verdoux: Sympathy for the Devil an essay by Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at the Criterion Collection