Mount Kidd

Mount Kidd is a 2,958-metre (9,705-foot) double-summit massif centrally located in Kananaskis Country in the Canadian Rockies of Alberta, Canada. Mount Kidd is situated within Spray Valley Provincial Park, and its nearest higher neighbor is Mount Sparrowhawk, 7.0 km (4.3 mi) to the northwest.[3] Mount Kidd is a landmark that can be seen from Highway 40 in the Kananaskis Village area, and from the Kananaskis Country Golf Course which lies at the eastern base of the mountain.

| Mount Kidd | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Mount Kidd seen from northbound Highway 40 with south peak on left and north peak on right | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,958 m (9,705 ft)[1][2] |

| Prominence | 535 m (1,755 ft)[1] |

| Parent peak | The Tower (3117 m)[1] |

| Isolation | 3.84 km (2.39 mi)[3] |

| Listing | Mountains of Alberta |

| Coordinates | 50°53′37″N 115°11′23″W[4] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | John Alfred (Fred) Kidd |

| Geography | |

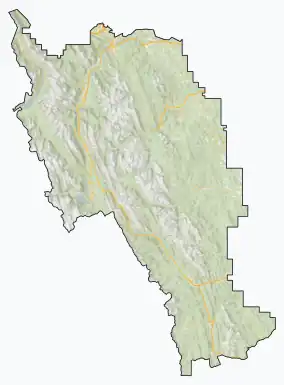

Mount Kidd Location in Kananaskis Country  Mount Kidd Location in Alberta | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Alberta |

| Protected area | Spray Valley Provincial Park |

| Parent range | Kananaskis Range[3] Canadian Rockies |

| Topo map | NTS 82J14 Spray Lakes Reservoir[4] |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Cambrian |

| Type of rock | sedimentary rock |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1947 by R. C. Hind and J.F. Tarrant[1] |

| Easiest route | Scramble |

History

In 1907, Dr. Donaldson Bogart Dowling, an engineer with the Geological Survey of Canada, named the mountain for John Alfred (Fred) Kidd, who was a resident of nearby Morley, Alberta.[5][6] From 1902 to 1907, Kidd ran the Morley general store and outfitted expeditions and geological survey crews such as Dowling's with supplies. The first ascent of the mountain was made in 1947 by R. C. Hind and J. F. Tarrant.[1] The mountain's name was officially adopted in 1953 by the Geographical Names Board of Canada.[4] In June 1986, Mount Kidd was the scene of the first of three related airplane crashes known as the Rescue 807 Crashes. In August 2010, James Hoshizaki stepped onto a snow cornice to pose for a photo when it gave way, resulting in an avalanche that swept him down about 200 metres to his death.[7]

Geology

Mount Kidd is composed of sedimentary rock laid down during the Precambrian to Jurassic periods. Formed in shallow seas, this sedimentary rock was pushed east and over the top of younger rock during the Laramide orogeny.[8] The Lewis Overthrust extends over 450 km (280 mi) from Mount Kidd south to Steamboat Mountain, located west of Great Falls, Montana.[9] Mount Kidd marks the northern end of the Lewis Thrust Fault.

Climate

Based on the Köppen climate classification, Mount Kidd is located in a subarctic climate zone with cold snowy winters and mild summers.[10] Temperatures can drop below −20 °C (−4 °F) with wind chill factors below −30 °C (−22 °F). Weather conditions during winter make Mount Kidd one of the better places in the Rockies for ice climbing. Precipitation runoff from the mountain drains into the Kananaskis River which is a tributary of the Bow River, and thence the Saskatchewan River.

Climbing

Mount Kidd has two summits, a north and south peak, each with scramble routes. The more massive north peak is the true summit at 2,958 m (9,705 ft), whereas the lesser south peak rises to 2,895 m (9,498 ft).[11] Additionally, Mount Kidd has a class 5.7 rock climbing route on its northeast buttress,[12] as well a 5.8 route called The Fold on the south peak.[13] In 1985, Rudi Kranabitter and Ferdl Taxbock made the first ascent of this now-classic route.[14]

Ice Climbing Routes with grades on Mount Kidd:[15]

- A Bridge Too Far – WI4+

- Kidd Falls – WI4

- Tasting Fear – WI5−

- Wedge Smear – WI3

- Sinatra Falls – WI2

Gallery

References

- "Mount Kidd". Bivouac.com. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

- "Topographic map of Mount Kidd". opentopomap.org. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- "Mount Kidd, Canada". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- "Mount Kidd". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada. Retrieved 2018-11-11.

- "Mount Kidd". cdnrockiesdatabases.ca. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- Kane, Alan (2016). Scrambles in the Canadian Rockies (3rd ed.). Rocky Mountain Books. p. 174.

- "Climber dies in Alberta mountain plunge". CBC News. August 10, 2010. Retrieved 2023-08-22.

- Gadd, Ben (2008), Geology of the Rocky Mountains and Columbias

- Feinstein, Shimon; Kohn, Barry; Osadetz, Kirk; Price, Raymond A. (2007-01-01). "Thermochronometric reconstruction of the prethrust paleogeothermal gradient and initial thickness of the Lewis thrust sheet, southeastern Canadian Cordillera foreland belt". Geological Society of America Special Papers. 433: 167–182. doi:10.1130/2007.2433(08). ISBN 978-0-8137-2433-1. ISSN 0072-1077.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L. & McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen−Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. S2CID 9654551.

- "Mount Kidd South Peak, Canada". Peakbagger.com.

- Dougherty, Sean Melbourne (1991). Selected alpine climbs in the Canadian Rockies. Rocky Mountain Books.

- Journal Alpin Canadien, Volume 79, 1996, pg 104

- "Four Bighorn Highway Alpine Rock Moderates". Gripped magazine. Toronto, Ontario. 23 July 2019. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Climbing in Mount Kidd, Alberta". Mountain Project. Adventure Projects, Inc. / REI co-op. 10 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

External links

- Mount Kidd weather web site: Mountain Forecast

- Drone video at Mount Kidd: YouTube

- Mt. Kidd reflection photo: Flickr

.jpg.webp)