Mer (community)

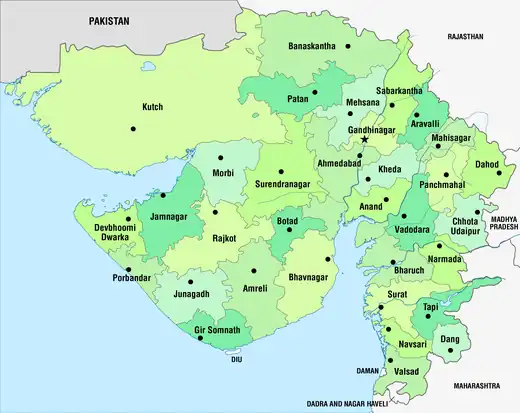

Mer, Maher or Mehar (Gujarati: ISO 15919: Mēr, Mahēr, Mēhar Sanskrit: मेर, महेर, मेहर; Gujarati: મેર, મહેર, મેહર; IPA: mer, məher, mehər) is a kshatriya caste from the Saurashtra region of Gujarat in India.[1][2][3] They are largely based in the Porbandar district, comprising the low-lying, wetland Ghēḍ and highland Barḍā areas, and they speak a dialect of the Gujarati language.[4][5][6] The Mers of the Ghēḍ and Barḍā form two groups of the jāti and together they are the main cultivators in the Porbandar District.[7] Historically, the men served the Porbandar State as a feudal militia, led by Mer leaders.[8][9] In the 1881 Gazette of the Bombay Presidency, the Mers were recorded numbering at 23,850.[10] The 1951 Indian Census recorded 50,000 Mers.[11] As of 1980 there were estimated to be around 250,000 Mers.[12]

મેર, મહેર | |

|---|---|

Mer Rās(Maniyaro)(મણિયારો) | |

| Total population | |

| 250,000 (1980) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Porbandar district, Junagadh district, Devbhumi Dwarka district, Jamnagar district, Europe | |

| Languages | |

| Gujarati | |

| Religion | |

| Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Gujarati people |

Origin

Mers of other lineages consider the Kēshwaḷā as the earliest lineage citing the proverb: Ādya Mēr Kēshwaḷā, jēni suraj purē chē śakh - "the sun stands testimony to the fact that Kēshwaḷās are the original Mers." [13] An origin myth of the Kēshwaḷās descending from the neck hair of Rama was recorded by colonial authors.[9] However, possibly the oldest reference to Kēshwaḷās indicates that the founder of this lineage may have lived over a thousand years ago, although, this relies on the genealogies of Barots which are not considered completely accurate as they are projected back in time to pseudo-history.[14]

Mers were once associated with the Maitraka dynasty.[4][15] Sinha suggests that the word Maitraka is an adaption from Mihir, which is in turn an adaption from Mer and does not rule out the possibility that the ruling families of the Maitrakas originated from the Mers.[16] Inscriptions at the Vadava well of Cambay mentions Mers as having originated from the Solar dynasty. [17] Other historians believe that Mers have Hun origin. [18] [19]

History

A Mer dynasty existed in Eastern Saurashtra, as noted by an inscription discovered in Timana. In 1207 CE the ruler Jagamal was a vassal of Bhima II of the Chaulukyas.[20] Jagamal had founded the temples of Chandreshwar and Prathvidiveshwar (the last is still standing), and endowed them with 55 prājás of land from the village of Kāmlol and 55 prājás of land from the village of Phūlsar, Near the village of Kūnteli (the modern Kāndheli).[21]

A further inscription from Mahuva, Dated to 1215 CE mentions a Mer king named Ranasimha, proposed to be a successor of king Jagamal, in the same area.[20] The Hatasni inscription from 1328 describes the construction of a stepwell by Kuntaraja for the Mer ruler Thepak, who wanted to built a stepwell in his own name as his maternal uncle Khengar had done. Nagarjuna was born into the Vakhala family and his son Mahananda had Thepak by his wife Rupa, the daughter of Mandalik I. Thepak had been appointed to rule over Talaja by a Chudasama ruler named Mahisa.[22][23] The Sīsodiyā branch of Mers was formed when the Sisodia Hati Rajputs came from Mewar in Rajasthan to Saurashtra as mercenary warriors and settled at Malia Hatina (Malia of the Hatis) and intermarried with the local Ahirs and Mers.[24]

An inscription from Bhavnagar mentions the Mer as king of Dvija.[25]

The Arab historian Al-Baladhuri mentioned the Mers as being a powerful tribe residing in north-west Saurashtra.[26]

Mers were the dominant agricultural caste in the Jethwa-ruled kingdom around Barda.[27] Mers did not pay rent on their land, only paying a hearth tax and if they cultivated, a plough tax in addition to sukhḍi (quit rent) on villages assigned to them.[9] They would coronate the Jethwa ruler by placing a tilak upon his head.[28] Resultantly, Mers along with Kathis and Rajputs were considered to be 'Darbars'.[27] Historically, highland Mers, also known as Bhōmiyā (landed) held more political power than lowland Mers with the latter being restricted from buying land from Bhōmiyās between 1884 and 1947.[29] The kin of those slain in action were paid 100 rupees (£10) by the Rana during the late 1800s.[9] On the 28th April 1895, the Bharwads of Jamkhirasara (near Bhanvad) organised a collective wedding which was attended by 12,000 people, including large numbers of Mers and the Jam Sahib. Reportedly "places of honour" were reserved for them at the wedding feast and they were "held in most respect"[30] Keshav Bhagat who hailed from Dhandhusar became a radio star in the 1930s, singing traditional Gujarati bhajans, dohas and sorthas.[31]

In the 1970s Sarman Munja Jadeja rose to prominence after killing gangsters Devu and Karsan Vagher who had been hired by Nanji Kalidas Mehta to break the strike at the Maharana Mills.[32] As the leader of organised crime in Porbandar he ran a parallel system of justice and was hailed by many Mers as a Robin Hood-like figure.[33] After killing 47 people, he renounced violence having been influenced by the Swadhyay Movement.[32] In 1986 he was murdered by a rival gang resulting in Santokben Jadeja taking over her husbands gang and killing 30 people to take revenge.[32] By the 1990s her gang was wanted in 500 cases and she in 9. Shantokben died in 2011, following which a rival ganglord, Bhima Dula Odedara became dominant in local crime and politics.[34] Odedara took control of the profitable limestone, chalk and bauxite mines; he was given double life imprisonment by the Gujarat High Court for double murder in 2017.[33][35]

Mers in politics

Mers have dominated the politics of the Kutiyana Vidhan Sabha, the Porbandar Vidhan Sabha and the Porbandar Lok Sabha seats.

.svg.png.webp)

The first Mer to become the MLA for Kutiyana was Indian National Congress member Maldevji Odedra in 1962; who also became the Gujarat Congress President. 1980 saw Congress candidate Vijaydasji Mahant elected and he retained his seat in 1985. Mahant also became the Gujarat Congress President.[36] In 1990 Santokben Jadeja won the Kutiyana assembly seat as a Janata Dal candidate. In 1995 her brother-in-law Bhura Munja Jadeja became the MLA for Kutiyana contesting as an independent. After the Jadejas, the Bharatiya Janata Party candidate Karsan Dula Odedara held the Kutiyana seat winning in 1999, 2002 and 2007. Since 2012 it has been held by Kandhal Jadeja a Nationalist Congress Party MLA and son of Santokben, who won again in 2017.[37]

Maldevji Odedra was elected from the Porbandar Vidhan Sabha seat in 1972 as an INC candidate. In 1985, Laxmanbhai Agath (INC) was elected. Babubhai Bokhiria (BJP) held the seat in 1995 and 1998, losing to Congress candidate Arjunbhai Modhwadiya in 2002. Modhwadiya maintained his seat in 2007 and became the Gujarat Congress President, but lost to Babubhai Bokhiria, who currently is the MLA for Porbandar, in 2012 and 2017.[36][37]

Maldevji Odedra held the Porbandar Lok Sabha seat in 1980 on behalf of INC. His son, Bharatbhai Odedra (INC) was elected in 1984 from Porbandar to the Lok Sabha.

Clans

The community is endogamous, that is, marriages take place within the community, but exogamous with respect to clan. That is the bride and groom belong to different clans (gotra) known as Bhāyāt. Genealogies of Mer families are maintained by Barots through name recording ceremonies.[38] Patel or headmen is a hereditary title held by family elders who take part in all religious and secular functions.[39] Generally every Mer village is dominated by one of the clans, however, other clans move in as gharjemai (men who live in the houses of their fathers'-in-law when their fathers-in-law have no heir). They are often followed by other relatives.[40] Mers consist of 14 clans called Śakh which are further split into segments called Pankhī:[4][41]

- Bhaṭṭi

- Chauhāṇ

- Chavḍa

- Chūḍāsamā

- Jāḍējā

- Kēshwaḷā

- Ōḍēdarā

- Parmār

- Rājshākhā

- Sīsodiyā

- Sōlaṁkī

- Vāḍhēr

- Vaghēlā

- Vāḷā

Society and culture

Lifestyle

A 1980 study of the Mers estimated that: an average Mer household contains 6 people, 35% were literate, 95% of households owned their homes and 77% of household members were employed. 77% of those employed worked in the agricultural sector.[42] Mers grow pearl millet (Bājarō), sorghum (Jōwār) and fodder as staple crops, along with wheat where possible. Cotton and peanuts are grown as cash-crops, while vegetables include chillies, clover, aubergines, tomatoes, turnips. Rarely sugarcane, castor and pulses are grown as well. Owing to their consumption of dairy products, cattle and water buffaloes are bred. Prosperous Mers own horses.[40] Small scale plant-based industries are run by Mers, including bio-diesel production from the Mōgali āranḍ (Jatropha curcus L), herbal shampoo from Aloe and ground nut, sesame and castor oil extracting mills.[40] Poorer Mers without lands to their name, undertake quarrying, cutting and stone-working.[43]

Mers are mostly vegetarian, with pearl millet (Bājarō), sorghum (Jōwār) and wheat rotis being consumed with vegetables, chillis and curds.[10] During weddings jaggery, ghee, lāpsi and khichdi is served.[44] As of 1976, it has been reported that vices are common amongst Mers with around 30% consuming alcohol despite the prohibition in Gujarat.[44]

Historically, Mers were wedded through arranged marriages, which were agreed between the parents of two new-borns. However, a girl married as a child would only be sent to live with her husband's family after achieving maturity.[45] Cross-cousin marriage was common, while polygamous marriages were rare, only being permitted if a man was unable to have children with his first wife.[45] The women of this community do not observe female seclusion norms, widow remarriage was not prohibited and menstruation seclusion taboos are not followed.[38][46] Dowry operates largely in the favour of women.[45] Differing from typical Hindu weddings, the Khaṁḍūṁ ceremony involves a sword being wed as a proxy for the groom. Grooms wear a jūmaṇuṁ made of twenty tolas of gold which has either been passed down or borrowed from relatives.[47] Modern transport and equipment such as orchestra troupes are employed.[47] Dates would be distributed in a custome called Lāṇ, to fellow villagers to celebrate a wedding or the birth of a son.[48] Wedding processions are taken out in a gāḍū, a traditional bullock cart which transports women from the bridegrooms's side to the bride's home in the jān.[49] Mers are Kshatriyas.[1] However, in the local caste system, Vaishyas would not consume food from Mers due to their consumption of meat and alcohol.[50] Mers are considered part of the Kānṭio Varna or haughty groups that included other tribes such as Rajputs and Ahirs.[51] The Tēr Tāṁsḷī (13 bell-metal bowls) a group of thirteen communities that dine together but do not intermarry, includes the Mers.[52] Vasvāyā - crafstmen, merchants and the barber are considered to be rūp or the beauty of the village by Mers.[40] Mers and Rabaris maintained a symbiotic relationship with every Mer-majority village having Rabari families, who would manage the village herd and sell dairy products from their own animals.[27] In 1993 the Mandal Commission classified the Mers as an Other Backward Class.[53]

Mer men used to wear umbrella shaped gold earrings called Śiṁśorīya; while Mer women wore bead shaped Vedla. Men also wore malas with alternating red and gold coral beads.[54] Mer women also tattooed large parts of their body including the neck, arms and legs.[55][56] Mer women were usually tattooed when they were about seven or eight years old. The hands and feet are marked first and then the neck and chest. It is customary for a girl to be tattooed before marriage.[57] A Mer proverb states 'We may be deprived of all things of this world but nobody has the power to remove the tattoo marks".[58] Mer tattoo motifs have a close relation to secular and religious subjects of devotion. Designs include holy men, feet of Rama or Lakshmi, women carrying water in pitchers on their head, Shravan carrying his parents on a lath (kāvad) to centers of pilgrimage, and popular gods like Rama, Krishna and Hanuman are also depicted. The lion, tiger, horse, camel, peacock, scorpion, bee and fly are other favorites.[57] Mēr nō Rās (Dance of the Mer) a unique form of dandiya raas is performed. The performance includes liberal dusting of Gulal (vermillion) on the bodies and costumes of the dancers.[59] The practice of the dance is noted by colonial authors, where they describe its performance with both the stick and sword variation, during a collective wedding or "Bharwad Jang" of the Bharwads of Jamkhirasara near Bhanvad.[30] Mers keep a variety of weapons including battleaxes, swords, lances, guns and shields. In particular the battleaxe is used as an purpose instrument and is seen as an emblem of manhood.[60]

Religion

Beliefs and practices

Mers are Hindus and practise a variety of religious traditions ranging from Folk Hinduism to Yogic and Bhakti practises. In addition, each lineage also has a lineage deity or Kuldevi, referred to as Āī (grandmother) who is worshipped by lighting a lamp in front of the murti.[61] While Mers worship all gods of the Hindu pantheon, devotion to Ramdevji and Vachharadada is a unique hallmark of Mer religious belief. Mer men and women maintain complete freedom in choosing panth or sampradaya and no member of a family forces another to follow their denomination.[62] Mer men are expected to have a guru to provide personal religious advice; those without one are disparagingly called nagūrū (without a guru).[63]

The worship of Ramdev Pir is also formalised through a panth focusing on the worship of jyot and the secret Pāt ceremony is organised, breaking all caste and societal barriers.[64] The Mers of Ghēḍ organise the Manḍap ceremony with Kolis and bring entire villages together in worship.[65] Bhakti tradition is practised through the singing of bhajans about the Hindu epics; jiva; brahman; jnana; sannyasa; bhakti and moksha.[45][66] Vaishnavism, Shaivism and Shaktism are found amongst the Mers, with every village containing a temple to Shiva, Rama, and various forms of Devi. Amidst the worshippers of Devi, the presence of a small minority of secret Vamachara practitioners has also been noted; they are reputed to worship Kali with meat and alcohol.[64] Within the Bhakti tradition the Pranami Sampraday is prevalent and devotees worship Krishna as Gopis.[67] The Kabir panth also has a small following, functioning in open ceremonies under the guidance of a mahant.[68] Some Mers follow Pirs based on individual experiences.[69] Typical forms of Hindu worship such as aarti are common. Satis of the Charan jāti including Khodiyar are highly revered.[70][71] When praying to Kuldevis, Satis or Vachhara Dada, the services of a bhuvā (shaman) are employed.[71] Around marriage the goddess Randal is worshipped for fertility, while Brahmins are invited to recite the Satyanarayan Katha to pray for relief from difficult times.

Mers commission three types of Paliyas to venerate their ancestors. The first type is for surāpurā (lit. perfect brave, referring to warriors); the second for surdhan for ancestors who have died an unnatural death and finally for satis. They are venerated with sindoor by Mer descendants on Diwali.[72][73] One occasion on which Paliyas are venerated, is weddings, where permission for marriage is taken from ancestors. In addition consent is also taken from Vachharadada.[74]

Festivals and pilgrimages

Melas are fairs organised on religious occasions but also have secular aspects. The largest fair of the Mer region is the Madhavpur Mela. The Mer community annually celebrates 'Rukmini no Choro', at the beautiful Madhavrai Temple. It is believed that Krishna married Rukmini in Madhavpur.[75] Mers also attend regional fairs such as the Maha Shivratri Mela in Bhavnath, Junagadh and the mela at the Bileshwar Mahadev Temple in the Barda Hills.[76] On Bhim Agyaras other fairs are organised in Odadar and Visavada in the highland and Balej in the low-land.[77] Momai Mata is venerated by Mers and Rabaris and the favour of the goddess is sought for the protection of cattle and for a good monsoon.[78] Mers go on pilgrimage to Dwarka. Another common pilgrimage is to Mount Girnar.[79]

Celebrations of Holi begin after the lighting of the Rabari Holi at Kanmera Nes in the Barda Hills is spotted in the plains villages. The Rabaris act as an intermediary to sacred powers by inviting the spirits of Puranic and Vedic figures to their Holi.[78]

Diaspora

Mers started migrating to the British colonies in East Africa during early parts of 20th century. The businessman, Nanji Kalidas Mehta was instrumental in helping them to migrate to Africa. Many of the early migrants were from the highlands villages.[80] Following the expulsion of Asians from Uganda many Mers settled in Britain and other Western countries.[81]

Notable people

Science

- Kamlesh Khunti CBE - director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands and globally recognised diabetes expert.[39]

Sports

- Sonia Odedra - English female Cricketer

- Jayesh Odedra - Indian Cricketer

- Jay Odedra - Omani cricketer

- Prem Sisodiya -Welsh Cricketer

Politics

- Babubhai Bokhiria - Gujarat Cabinet Minister for Water Resources (except Kalpsar project), Agriculture, Animal Husbandry, Fisheries and Cow protection[82]

- Arjun Modhwadia - Indian politician[82]

- Santokben Jadeja - Indian politician [83]

- Kandhal Jadeja - Son of Santokben and member of Gujarat legislative assembly [82]

References

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 1, 14, 40.

- Diskalkar, D B (1941). "Inscriptions of Kathiawad". New Indian Antiquary. 1: 580 – via Archiv.org.

The Mahuva inscription of v.s. 1272 speaks of a Mehara king ruling at Timbanaka. He was probably a successor of the Mehar king Jagaraal, a feudatory of the Caulukya sovereign Bhima II mentioned in the copperplate grant of v.s. 1264 found at Timana and published in the Indian Antiquary Vol. XI p. 337. Another Meher family is mentioned in the Hataspi inscription of v.s. 1386. In modem times the Mehers are found chiefly in the Porbunder State and not in the part of Kathiawad where the abovementioned inscriptions were found.

- Fischer, Eberhard; Shah, Haku (1970). Rural craftsmen and their work: Equipment and techniques in the Mer village of Ratadi, in Saurashtra India. Paldi, Ahmedabad: National Institute of Design. p. 118.

- Franco, Fernando; Macwan, Jyotsna; Ramanathan, Suguna (2004). Journeys to Freedom: Dalit Narratives. Popular Prakashan. pp. 242–. ISBN 978-81-85604-65-7. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Trivedi 1986, p. viii.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 1–3.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 100–103.

- Maddock 1993, p. 104.

- Campbell 1881, p. 138.

- Campbell 1881, p. 139.

- Trivedi 1999, p. 1.

- Trivedi 1999, p. 9.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 106.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 107–108.

- Odedra, N. K. (2009). Ethnobotany of Maher tribe in Porbandar district, Gujarat, India (PDF) (PhD thesis). Saurashtra University. p. 87.

- Sinha, Nandini (August 1, 2001). "Early Maitrakas, Landgrant Charters and Regional State Formation in Early Medieval Gujarat". Studies in History. 17 (2): 153–154. doi:10.1177/025764300101700201. S2CID 162126329.

- Rūpamañjarīnāmamālā 1983, pp. 8.

- History of Gujarat 1982, pp. 81.

- Encyclopaedia Indica: Ancient Gujarat 2000, pp. 132.

- Diskalkar, D B (1941). "Inscriptions of Kathiawad". New Indian Antiquary. 1: 580 – via Archiv.org.

The Mahuva inscription of v.s. 1272 speaks of a Mehara king ruling at Timbanaka. He was probably a successor of the Mehar king Jagaraal, a feudatory of the Caulukya sovereign Bhima II mentioned in the copperplate grant of v.s. 1264 found at Timana and published in the Indian Antiquary Vol. XI p. 337. Another Meher family is mentioned in the Hataspi inscription of v.s. 1386. In modem times the Mehers are found chiefly in the Porbunder State and not in the part of Kathiawad where the abovementioned inscriptions were found.

- Gujarat State Gazetteers: Bhavnagar 1969, pp. 616.

- Diskalkar, D.B (1938–1941). Inscriptions of Kathiawad (No. 27). Pune.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sheikh, Samira (2008). "Alliance, Genealogy and Political Power". The Medieval History Journal. 11 (1): 36. doi:10.1177/097194580701100102. S2CID 154992468 – via SAGE.

- Shah, A. M.; Desai, I. P. (1988). Division and hierarchy : an overview of caste in Gujarat. South Asia Books. p. 60. ISBN 978-8170750086.

- Inscriptions of Kathiawad 1939, pp. 732.

- Gujarat as the Arabs Knew it 1969, pp. 31.

- Tambs-Lyche, Harald (1997). Power, Profit and Poetry Traditional Society in Kathiawar, Western India. New Delhi: Manohar. pp. 160–161. ISBN 81-7304-176-8.

- Cousens, Henry (1998). Somanatha and Other Mediaeval Temples in Kathiawad. Archaeological Survey of India. p. 3.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 101.

- Campbell, James M. (1901). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency Volume 11 Part 1. Gujarat Population: Hindus. Bombay: Government Central Press. p. 275.

- "Gujrathi and Hindustani records". British Library Endangered Archives Programme. 1937-12-01. Archived from the original on 2022-04-04. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- Pandya, Haresh (24 May 2006). "Bapu's children swear by guns". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Menon, Aditya (9 December 2017). "Gangs of Porbandar: How Gujarat polls are the latest act in old mafia rivalries". Catch News. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Dave, Hiral (2 April 2011). "Porbandar mourns its Godmother". The Indian Express. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "HC gives Bhima Dula life for double murder". Times of India. 14 October 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Congman who bucks the wave". The Indian Express. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Porbandar (Gujarat) Assembly Constituency Elections". Elections.in. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 60.

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 4.

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 6.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 100, 111.

- Trivedi 1999, pp. 20–38.

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 25.

- Trivedi 1999, p. 83.

- Trivedi 1999, p. 71.

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 120.

- Trivedi 1999, p. 80.

- Trivedi 1961, p. .

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 17.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 44.

- Trivedi 1999, p. 183.

- Trivedi 1999, pp. 184–185.

- "Central List of OBCs". National Commission for Backward Classes. 10 September 1993. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 114-115.

- "Shinshoria – a traditional ear ornament". People's Archive of Rural India. 2015-02-16. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- "Vedla – earrings of the Maher community". People's Archive of Rural India. 2015-02-16. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- Krutak, Lars. "India: Land of Eternal Ink".

- TRAVELS THROUGH GUJARAT, DAMAN, AND DIU. Lulu.com. 22 February 2019. ISBN 9780244407988.

- Sharma, Manorma (1 January 2007). Musical Heritage Of India. APH Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 978-81-313-0046-6. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 108-109.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 173–175.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 163.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 163–164.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 158.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 63.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 153.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 157–158, 160.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 161.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 162.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 155.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 175.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 177.

- Maddock 1993, pp. 108–110.

- Fischer & Shah 1970, p. 43-45.

- Desai, Anjali H. (2007). India Guide Gujarat. India Guide Publications. ISBN 978-0978951702.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 183–188.

- Trivedi 1961, p. 187.

- Tambs-Lyche, Harald (1997). Power, Profit and Poetry Traditional Society in Kathiawar, Western India. New Delhi: Manohar. pp. 160–161. ISBN 81-7304-176-8.

- Trivedi 1961, pp. 156–157.

- Trivedi 1986, p. 21.

- Joshi, Swati (2 December 2000). "'Godmother': Contesting Communal Politics in Drought Land". Economic and Political Weekly. 35 (49): 4304–4306.

- "Gangs of Porbandar: How Gujarat polls are the latest act in old mafia rivalries". CatchNews.com. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- Joshi, Rajesh (8 March 1999). "Santokben, Godmother". Outlook India. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

Sources

- Campbell, James, M (1881). Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Vol. 8: Kathiawar. Bombay: Government Central Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Maddock, P (1993). "Idolatry in western Saurasthra: A case study of social change and proto‐modern revolution in art". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. Journal of South Asian Studies. 16: 101–126. doi:10.1080/00856409308723194.

- Trivedi, Harshad, R (1961). "A Study of the Mers of Saurashtra: An exposition of their social structure and organization". University. Vadodara: Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. hdl:10603/59823. OCLC 551698930.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Trivedi, Harshad, R (1986). The Mers of Saurashtra revisited and studied in the light of socio-cultural change and cross-cousin marriage. Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788170220442.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Trivedi, Harshad, R (1999). The Mers of Saurashtra : A profile of social, economic, and political status. Delhi: Devika Publications. ISBN 9788186557204.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)