History of Gujarat

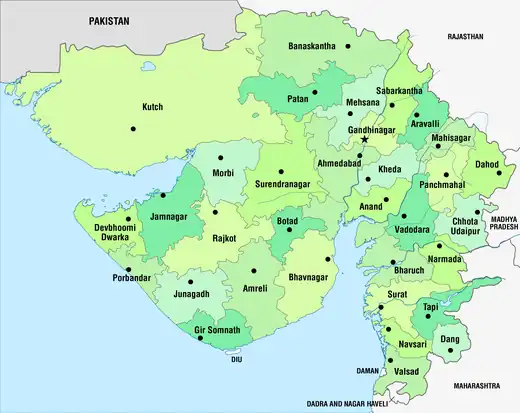

The history of Gujarat began with Stone Age settlements followed by Chalcolithic and Bronze Age settlements like Indus Valley civilisation.[1] Gujarat's coastal cities, chiefly Bharuch, served as ports and trading centers in the Nanda, Maurya, Satavahana and Gupta empires as well as during the Western Kshatrapas period. After the fall of the Gupta empire in the 6th century, Gujarat flourished as an independent Hindu-Buddhist state. The Maitraka dynasty, descended from a Gupta general, ruled from the 6th to the 8th centuries from their capital at Vallabhi, although they were ruled briefly by Harsha during the 7th century. The Arab rulers of Sindh sacked Vallabhi in 770, bringing the Maitraka dynasty to an end. The Gurjara-Pratihara Empire ruled Gujarat after from the 8th to 10th centuries. While the region also came under the control of the Rashtrakuta Empire. In 775 the first Parsi (Zoroastrian) refugees arrived in Gujarat from Greater Iran.[2]

| History of Gujarat |

|---|

During the 10th century, the native Chaulukya dynasty came to power. From 1297 to 1300, Alauddin Khalji, the Turkic Sultan of Delhi, destroyed Anhilwara and incorporated Gujarat into the Delhi Sultanate. After Timur's sacking of Delhi at the end of the 14th century weakened the Sultanate, Gujarat's governor Zafar Khan Muzaffar asserted his independence and established the Gujarat Sultanate; his son, Sultan Ahmad Shah I (ruled 1411 to 1442), restructured Ahmedabad as the capital. In the early 16th century the Rana Sanga invasion of Gujarat weakened the Sultanate's power as he annexed northern Gujarat and appointed his vassal to rule there, however after his death, the Sultan of Gujarat recovered the kingdom and even sacked Chittor Fort in 1535.[3] The Sultanate of Gujarat remained independent until 1576, when the Mughal emperor Akbar conquered and annexed it to the Mughal Empire as a province. Surat had become the prominent and main port of India during Mughal rule.

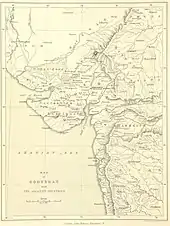

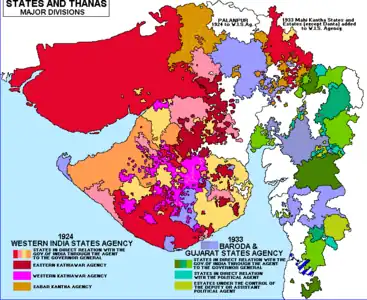

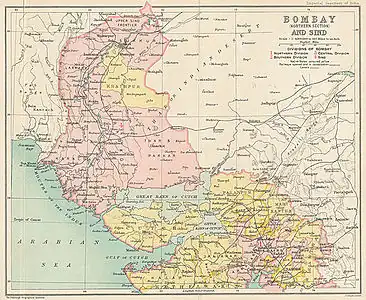

Later in the 18th century, Gujarat came under control of the Maratha Empire who dominated the politics of India. The British East India Company wrested control of much of Gujarat from the Marathas during the Second Anglo-Maratha War. Many local rulers, notably the Gaekwads of Baroda, made a separate peace with the British and acknowledged British sovereignty in return for retaining local self-rule. Gujarat was placed under the political authority of the Bombay Presidency, with the exception of Baroda state, which had a direct relationship with the Governor-General of India. From 1818 to 1947, most of present-day Gujarat, including Kathiawar, Kutch, and northern and eastern Gujarat were divided into hundreds of princely states, but several districts in central and southern Gujarat were ruled directly by British officials. Mahatma Gandhi, considered India's "father of the nation", was a Gujarati who led the Indian Independence Movement against British colonial rule.[4]

Gujarat was formed by splitting Bombay state in 1960 on linguistic lines. From 1960 to 1995, the Indian National Congress retained power in the Gujarat Legislative Assembly while other political parties ruled for incomplete terms in the 1970s and 1990. The Bharatiya Janata Party has been in power since 1998.

Early history (before 4000 BCE)

The cultural history of Gujarat begins from the Middle Pleistocene. The lands of Gujarat has been continuously inhabited from the Lower Paleolithic (c. 200,000 BP) period. Several sites of Stone Age are discovered in riverbeds of Sabarmati, Mahi river and lower Narmada rivers of Gujarat.[5][6]

The Middle Paleolithic sites are found from Kutch, Jamnagar, Panchmahals, Hiran valley in Saurashtra and Vapi and Lavacha of Valsad district. The Upper Paleolithic period sites from Visadi, Panchmahals, Bhamaria, Kantali, Palanpur and Vavri are also explored.[5] The Middle (c.45,000–25,000 BP) and Late Palaeolithic artifacts include hand-axes, cleavers, chopping tools, borers, points, and scrapers.[7] The sites in Kutch and Bhadar riverbeds in Saurashtra has also yielded Stone Age tools. Bhandarpur near Orsang valley is rich in Palaeolithic tools. Some of other such sites are Hirpura, Derol, Kapadvanj, Langhnaj and Shamlaji.[8]

More than 700 sites are located in Gujarat which indicate Mesolithic/Microlithic using communities dated to 7000 BC to 2000 BCE divided in Pre-Chalcolithic and Chalcolithic period.[9] Some Mesolithic sites include Langhnaj, Kanewal, Tarsang, Dhansura, Loteshwar, Santhli, Datrana, Moti Pipli and Ambakut. The people of the Mesolithic period were nomadic hunter-gathers with some managing the herds of sheep-goat and cattle.[5][10] Neolithic tools are found at Langhnaj in north Gujarat.[11]

Chalcolithic to Bronze Age (4000–1300 BCE)

Total 755 chalcolithic settlements are discovered in Gujarat belonging to various traditions and cultures which ranged from 3700 BCE to 900 BCE. Total 59 of these sites are excavated while others are studied from artifacts. These traditions are closely associated with Harappan civilization and difference between them is identified by difference in ceramics and findings of microliths. These traditions and cultures include Anarta Tradition (c. 3950–1900 BCE), Padri Ware (3600–2000 BCE), Pre-Prabhas Assemblage (3200–2600 BCE), Pre Urban Harappan Sindh Type Pottery (Burial Pottery) (3000–2600 BCE), Black and Red Ware (3950–900 BCE), Reserved Slip Ware (3950–1900 BCE), Micaceous Red Ware (2600–1600 BCE). Prabhas Assemblage (2200–1700 BCE) and Lustrous Red Ware (1900–1300 BCE) are some late material cultures. The few sites associated with Malwa Ware and Jorwe Ware are also found.[9]

.jpg.webp)

Gujarat has a large number of archaeological sites associated with the Indus Valley civilization. A total of 561 Classical Harappan (2600–1900 BCE) and Sorath Harappan (2600–1700 BCE) sites are reported in Gujarat.[9] The sites in Kutch, namely, Surkotada, Desalpur, Pabumath and Dholavira are some major sites of Urban period. The sites of the post-Urban period include Lothal B, Rangpur IIC and III, Rojdi C, Kuntasi, Vagad I B, Surkotada 1C, Dholavira VI &VII.[5] It has been noted that in Gujarat, urban cities quickly expanded rather than the slow evolution of urbanism in the northwest.[12]

.png.webp)

During the end of the Indus Valley Civilisation, there was a migration of people from Sindh to Gujarat forming the Rangpur culture.[13][14]

Iron Age (1500–200 BCE)

The post-Harappan culture continued at several sites. Pastoralism was also widespread and served as trade-links between the sites.[15][16] There is no mention of Gujarat in Vedic literature.[17] Bharuch was the major port town of Iron Age.[18]

Early Historic

The Early Historic material culture of Gujarat include the presence of Northern Black Polished Ware, continued dominance of Black-and-Red Ware, slow introduction and later domination of Red Polished Ware, occurrence of Roman Amphorae, Rang Mahal Ware (100–300), introduction of glass and lead, followed by gradual conquest of iron, an agriculture-based economy, shell industry, development of script, rise of the urban settlements, brick structural remains, monumental buildings, international trade and development of Jainism, Buddhism, and Vaishnavism.[5][19]

The excavated sites of the Early Historic period include Dhatva, Jokha, Kamrej, Karvan, Bharuch, Nagal, Timbarva, Akota from South Gujarat; Nagara from central Gujarat; Vadnagar, Shamlaji, Devnimori from north Gujarat and Amreli, Vallabhi, Prabhas Patan, Padri and Dwarka from Saurashtra.[5]Bharuch was the major port town of Iron Age.[18]

Mauryas

Candragupta Maurya's rule over present-day Gujarat is attested to by the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman. Under his rule, the provincial governor Puṣyagupta, a Vaiśya, started the construction of the Sudarśana lake by damming the Suvarṇasikatā and Palāśinī rivers which flowed from Mount Ūrjayat (modern Mount Girnār). The dam was completed under the reign of Aśoka by the Yavana king Tuṣāspha. What is now Gujarat comprised two provinces, Ānarta (northern mainland Gujarat and northern Kathiawar), and Surāṣṭra (southern Kathiawar).[20][21][22][23][24][25]

According to the Pettavattu and Paramatthadīpanī, a ruler of Suraṭṭha, Piṅgala became a king in 283 BCE. He was converted to "Natthika diṭṭhi" (a nihilistic doctrine) by his general, Nandaka, and attempted to convert the emperor Aśoka, but was himself converted to Buddhism.[22][26]

According to Kauṭilya, the Kṣatriyas and Vaiśyas of Surāṣṭra belong to various Śreṇīs "corporations or guilds". The Śreṇīs were devoted to the "possession of arms" or "agriculture, cattle-rearing, and trade" respectively.[22][27]

Indo-Greeks

There was a Greek trading presence at the port of Barugaza (Bharuch), but historians are uncertain whether the Indo-Greek Kingdom ruled over Gujarat.[28][29][30]

Indo-scythians

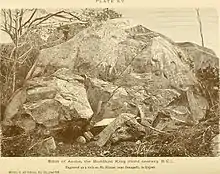

For nearly 300 years from the start of the 1st century CE, Saka rulers played a prominent part in Gujarat's history. Weather-beaten rock at Junagadh gives a glimpse of the Ruler Rudradaman I (100 CE) of the Saka satraps known as Western Satraps, or Kshatraps. Mahakshatrap Rudradaman I founded the Kardamaka dynasty which ruled from Anupa on the banks of the Narmada up to Aparanta region which bordered Punjab. In Gujarat several battles were fought between the south Indian Satavahana dynasty and the Western Satraps. The greatest ruler of the Satavahana Dynasty was Gautamiputra Satakarni who defeated the Western Satraps and conquered some parts of Gujarat in the 2nd century CE.[31]

Middle Kingdoms (230 BCE – 1297 CE)

Guptas and Maitrakas

The Gupta Emperor Samudragupta defeated the Indo-Scythian rulers in battle and had then admit their submission to him. Samudragupta's successor, Chandragupta II, finally conquered the Western Satraps and occupied Gujarat. Chandragupta II assumed the title of "Vikramaditya", in celebration of his victory over the Western Satraps.[32] During the Gupta reign, villagers and peasants were put into forced labour by the Gupta army and officials.[33] During the reign of Skandagupta, Cakrapālita was the governor of Surāṣṭra.[34]

Towards the middle of the 5th century the Gupta empire started to decline. Senapati Bhatarka, the Maitraka general of the Guptas, took advantage of the situation and in 470 CE he set up what came to be known as the Maitraka state. He shifted his capital from Girinagar to Valabhipur, near Bhavnagar, on Saurashtra's east coast. Maitrakas of Vallabhi became very powerful and their rule prevailed over large parts of Gujarat and even over adjoining Malwa. Maitrakas set up a university which came to be known far and wide for its scholastic pursuits and was compared with the famous Nalanda university. It was during the rule of Dhruvasena Maitrak that Chinese philosopher-traveler Xuanzang visited in 640 CE.

Gurjara-Pratihara Empire

In the early 8th century some parts of Gujarat was ruled by the south Indian Chalukya dynasty. In the early 8th century the Arabs of the Umayyad Caliphate established an Empire which stretched from Spain in the west to Afghanistan and Pakistan in the east. The Arab rulers tried to expand their Empire in the 8th century and invaded Gujarat but the Arab invaders were defeated by the Chalukya general Pulakeshin. After this victory the Arab invaders were driven out of Gujarat. Pulakeshin received the title Avanijanashraya (refuge of the people of the earth) by Vikramaditya II for the protection of Gujarat. In the late 8th century the Kannauj Triangle period started. The 3 major Indian dynasties the northwest Indian Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, the south Indian Rashtrakuta Dynasty and the east Indian Pala Empire dominated India from the 8th to 10th century. During this period the northern part of Gujarat was ruled by the north Indian Gurjara-Pratihara Dynasty and the southern part of Gujarat was ruled by the south Indian Rashtrakuta Dynasty.[36] Southern Gujarat was ruled by the south Indian Rashtrakuta dynasty until it was captured by the south Indian ruler Tailapa II of the Western Chalukya Empire.[37]

Chaulukya Kingdom

The Chaulukya dynasty[note 1][39] ruled Gujarat from c. 960 to 1243. Gujarat was a major center of Indian Ocean trade, and their capital at Anhilwara (Patan) was one of the largest cities in India, with population estimated at 100,000 in the year 1000. In 1026, the famous Somnath temple in Gujarat was destroyed by Mahmud of Ghazni. After 1243, the Chaulukyas lost control of Gujarat to their feudatories, of whom the Vaghela chiefs of Dholka came to dominate Gujarat. In 1292 the Vaghelas became tributaries of the Yadava dynasty of Devagiri in the Deccan. Karna of the Vaghela dynasty was the last Hindu ruler of Gujarat. He was defeated and overthrown by the superior forces of Alauddin Khalji from Delhi in 1297. With his defeat Gujarat not only became part of the Delhi Sultanate but the Rajput hold over Gujarat lost forever.

Delhi Sultanate (1297–1407)

Before 1300, Muslims had little presence in Gujarat. The occasional was mainly either as sea-farers or traders coming from Arabian Sea. They were allowed to establish two small settlements in Cambay (now Khambhat) and Bharuch. Gujarat finally fell under Delhi Sultanate following repeated expeditions under Alauddin Khalji around the end of the 13th century. He ended the rule of Vaghela dynasty under Karna II and established Muslim rule in Gujarat. Soon the Tughluq dynasty came to power in Delhi whose emperor carried out expeditions to quell rebellion in Gujarat and established their firm control over the region by the end of the 14th century.[40]

Gujarat Sultanate (1407–1535)

Following Timur's invasion of Delhi, the Delhi Sultanate weakened considerably so the last Tughluq governor Zafar Khan declared himself independent in 1407 and formally established Gujarat Sultanate. The next sultan, his grandson Ahmad Shah I founded the new capital Ahmedabad in 1411. The prosperity of the sultanate reached its zenith during the rule of Mahmud Begada. He subdued most of the Rajput chieftains and built navy off the coast of Diu. In 1509, the Portuguese wrested Diu from Gujarat sultanate following the Battle of Diu (1509).

In 1520 Rana Sanga of Mewar invaded Gujarat with his powerful Rajput confederacy of 52,000 Rajputs supported by his three vassals. Rao Ganga Rathore of Marwar too joined him with Garrison of 8,000 Rajputs, other allies of Rana were Rawal Udai Singh of Vagad and Rao Viram deva of Merta. He defeated the Muslim army of Nizam khan and chased them as far as Ahmedabad. Sanga call off his invasion 20 miles before reaching the capital city of Ahmedabad. He plundered the royal treasuries of Gujarat.[42] Sanga successfully annexed Northern Gujarat and appointed one of his vassals to rule there.[43]

Mughal emperor Humayun attacked Gujarat in 1535 and thereafter Bahadur Shah was killed by the Portuguese while making a deal in 1537. The decline of the Sultanate started with the assassination of Sikandar Shah in 1526. The end of the sultanate came in 1573, when Akbar annexed Gujarat in his empire. The last ruler Muzaffar Shah III was taken prisoner to Agra. In 1583, he escaped from the prison and with the help of the nobles succeeded to regain the throne for a short period before being defeated by Akbar's general Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana.[44]

Mughal Era (1535–1756)

Akbar (1542–1605) set out on his first campaign of Gujarat from Fatehpur Sikri on 2 July 1572 arriving in Ahmedabad on 20 November 1572.[45] He then reorganized the government of Ahmedabad under the charge of his foster brother Mirza Aziz Koka, the Khan-i-Azam[46] and quelled the rebellion led by the Mirzas by laying siege to the castle of Surat.[47] Akbar then embarked on a second campaign of Gujarat on 23 August 1573 to assist Mirza Aziz Koka against a rebellion from the combined forces of Muhammad Husain Mirza and Ikhtiyar-ul-Mulk.[48] Following Akbar's second campaign, Gujarat was organized into a province (subah) of the Mughal Empire[49] governed by viceroys (subahdars or nazims) responsible for the executive and military branches as well as treasurers (diwans) responsible for the financial branch.[50]

Gujarati ports with significant trade and financial importance now came into the possession of the Mughal Empire and were organized as special districts directly under the authority of the Delhi government.[51] Under Jahangir (1605–1627) and following the advent of the British East India Company, Surat gained importance as a center of oceanic trade between India and Europe;[52] a factory was established there in 1612.[53] The nobles of the former Sultanate and the Hindu chiefs that rebelled and protested were subdued by the viceroys and officers of the Mughal Empire.[54] Under Shah Jahan (1627–1658), Ahmedabad saw an exodus resulting from officials extracting money from citizens—both the rich and the poor—without the royal permission.[55] Viceroys under Shah Jahan saw to expansion efforts south,[56] taking up of arms against the incursions from the Koli and Kathi tribes,[57] and the implementation of a hardline stance on collection of tribute from the Rajput chiefs of Saurashtra.[58]

The reign of Aurangzeb (1658–1707) was characterized by incidents of drawn-out conflict and religious disputes. As a viceroy, he had previously converted the Chintamani Jain temple at Saraspur into a mosque.[59] His rule included enforcement of Islamic laws,[60] discriminatory laws and taxes against Hindu merchants,[61] and a capitation tax on all non-Muslims.[62] Aurangzeb's viceroys retaliated against the Khachars and other Kathi tribes,[63] destroyed the Temple of the Sun while attacking and storming the fort of Than,[64] razed the Temple at Vadnagar,[65] and engaged in a drawn out conflict with the Rathores of Marwar.[66]

During the next three emperors (1707–1719) who had brief reigns, the nobles became more powerful due to instability in the Delhi. The royals of Marwar were appointed viceroys frequently. During the reign of the emperor Muhammad Shah, the struggle between the Mughal and Maratha nobles were heightened with frequent battles and incursions.

Maratha Era (1718–1819)

When the cracks had started to develop in the edifice of the Mughal empire in the mid-17th century, the Marathas were consolidating their power in the west, Chhatrapati Shivaji, the great Maratha ruler, attacked Surat twice first in 1664 and again in 1672. These attacks marked the entry of the Marathas into Gujarat.

Later, in the 17th century and early 18th century, Gujarat came under control of the Maratha Empire. Most notably, from 1705 to 1716, Senapati Khanderao Dabhade led the Maratha Empire forces in Baroda. Pilaji Gaekwad, first ruler of Gaekwad dynasty, established the control over Baroda and other parts of Gujarat.

Starting with Bajirao I in the 1720s, the Peshwas based in Pune established their sovereignty over Gujarat including Saurashtra. After the death of Bajirao I, Peshwa Balaji Bajirao removed the control the Dabhades and Kadam Bande from Gujarat. Balaji Bajirao collected taxes through Damaji Gaekwad. Damaji established the sway of Gaekwad over Gujarat and made Vadodara his capital.[67]

The Marathas continued to grow their hold and the frequent change of viceroys did not reverse the trend. The competing houses of Marathas, Gaikwars and Peshwas engaged between themselves which slow down their progress for a while. They later made peace between themselves. During the reign of the next emperor Ahmad Shah Bahadur (1748–1754), there was nominal control over the nobles who acted on their own. There were frequent fights between themselves and with Marathas. Ahmedabad, the capital of province, fell to the Marathas in 1752. It was regained by noble Momin Khan for a short time but again lost to the Marathas in 1756 after a long siege. Finding opportunity, the British captured Surat in 1759. After a setback at Panipat in 1761, the Marathas strengthened their hold on Gujarat, especially during the reign of Madhavrao. [68]

Maratha control of Gujarat slowly waned in the 1780s and 1790s due to rivalries between different ruling Maratha houses as well within the Peshwa family. The British East India Company fully exploited this situation to expand its control of Gujarat and other Maratha territories.[69] The company also embarked upon its policy of Subsidiary Alliance. With this policy they established their paramountcy over one indigenous state after another. Anandrao Gaekwad joined the Alliance in 1802 and surrendered Surat and adjoining territories to the company. In the garb of helping the Marathas, the British helped themselves, and gradually the Marathas' power came to an end, in 1819 in Gujarat. Gaekwad and other big and small rulers accepted the British Paramountcy.[70]

Early trade with Europeans

In the 1600s, the Dutch, French, English and Portuguese all established bases along the western coast of the region. Portugal was the first European power to arrive in Gujarat, and after the Battle of Diu and Treaty of Bassein, acquired several enclaves along the Gujarati coast, including Daman and Diu as well as Dadra and Nagar Haveli. These enclaves were administered by Portuguese India under a single union territory for over 450 years, only to be later incorporated into the Republic of India on 19 December 1961 by military conquest.

The English East India Company established a factory in Surat in 1614, following the commercial treaty made with Mughal Emperor Nuruddin Salim Jahangir, which formed their first base in India, but it was eclipsed by Bombay after the English received it from Portugal in 1668 as part of the marriage treaty of Charles II of England and Catherine of Braganza, daughter of King John IV of Portugal. The state was an early point of contact with the west, and the first English commercial outpost in India was in Gujarat.[71]

17th-century French explorer François Pyrard de Laval, who is remembered for his 10-year sojourn in South Asia, bears witness accounts that the Gujaratis were always prepared to learn workmanship from the Portuguese, also in turn imparting skills to the Portuguese:[72]

I have never seen men of wit so fine and polished as are these Indians: they have nothing barbarous or savage about them, as we are apt to suppose. They are unwilling indeed to adopt the manners and customs of the Portuguese; yet do they regularly learn their manufactures and workmanship, being all very curious and desirous of learning. In fact, the Portuguese take and learn more from them than they from the Portuguese.

British Era (1819–1947 CE)

The East India Company wrested control of much of Gujarat from the Marathas during the Second Anglo-Maratha War in 1802–1803. Many local rulers, notably the Maratha Gaekwad Maharajas of Vadodara, made a separate peace with the British and acknowledged British sovereignty in return for retaining local self-rule.

Gujarat was placed under the political authority of the Bombay Presidency, with the exception of Baroda state, which had a direct relationship with the Governor-General of India. From 1818 to 1947, most of present-day Gujarat, including Kathiawar, Kutch and northern and eastern Gujarat were divided into hundreds of princely states, but several districts in central and southern Gujarat, namely Ahmedabad, Broach (Bharuch), Kaira (Kheda), Panchmahal and Surat, were governed directly by British officials. In 1812, an epidemic outbreak killed and wiped out half the population of Gujarat.[73]

Indian Independence Movement

See Also: Freedom fighters from Gujarat

The people of Gujarat were the most enthusiastic participants in India's struggle for freedom. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Morarji Desai, K.M. Munshi, Narhari Parikh, Mahadev Desai, Mohanlal Pandya and Ravi Shankar Vyas all hailed from Gujarat. It was also the site of the most popular revolts, including the Satyagrahas in Kheda, Bardoli, Borsad and the Salt Satyagraha.

Post-Independence (1947 CE – present)

1947–1960

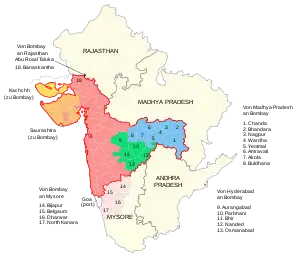

After Indian independence and the Partition of India in 1947, the new Indian government grouped the former princely states of Gujarat into three larger units; Saurashtra, which included the former princely states on the Kathiawar peninsula, Kutch, and Bombay state, which included the former British districts of Bombay Presidency together with most of Baroda state and the other former princely states of eastern Gujarat. In 1956, Bombay state was enlarged to include Kutch, Saurashtra, and parts of Hyderabad state and Madhya Pradesh in central India. The new state had a mostly Gujarati-speaking north and a Marathi-speaking south. Mahagujarat Movement led by Indulal Yagnik demanded splitting of Bombay state on linguistic lines. On 1 May 1960, Bombay state bifurcated into Gujarat and Maharashtra. The capital of Gujarat was Ahmedabad.[74]

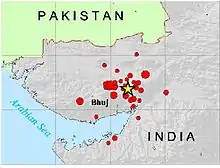

Kutch was hit by the earthquake in 1956 which destroyed major parts of Anjar town. Gandhidham, Sardarnagar and Kubernagar were refugee settlements established for the resettlement of Sindhi Hindu refugees arriving from Pakistan after partition.

1960–1973

Members of legislative assembly were elected from 132 constituencies of newly formed Gujarat state. Indian National Congress (INC) won the majority and Jivraj Narayan Mehta became the first chief minister of Gujarat. He served until 1963. Balwantrai Mehta succeed him. During Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, Mehta flew on aircraft to inspect Kutch border between India and Pakistan. The aircraft was shot down by Pakistan Air Force. Mehta was killed in the crash.[75][76] Hitendra Kanaiyalal Desai succeeded him and won assembly elections. In 1969, Indian National Congress split into Congress (O) headed by Morarji Desai and Congress (I) headed by Indira Gandhi.[77] At the same time, the Hindu nationalist organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) had established itself deeply in Gujarat around this period. The riots broke out across Gujarat in September to October 1969, resulting in large number of casualties and damage to properties. Desai resigned in 1971 due to split of INC and President's rule was imposed in Gujarat. Later Ghanshyam Oza became chief minister when Indira Gandhi led Congress (I) won majority in parliament after 1971 Indo-Pakistani war. Chimanbhai Patel opposed Oza and became chief minister in 1972. The capital of Gujarat moved from Ahmedabad to Gandhinagar in 1971 but legislative assembly building was completed in 1982.[78]

1974–2000

Navnirman Andolan, the "Navnirman movement" started in December 1973 due to price rise and corruption in public life. People demanded resignation of Chief Minister Patel.[79][80][81][82] Due to pressure of protests, Indira Gandhi asked Patel to step down. He resigned on 9 February 1974 and President's rule imposed.[79][81] The governor suspended the state assembly and President's rule was imposed. Opposition parties led stepped in with demand for dissolution of state assembly.[80] Congress had 140 out of 167 MLAs in state assembly. 15 Congress (O) and three Jan Sangh MLAs also resigned. By March, protesters had got 95 of 167 to resign. Morarji Desai, leader of Congress (O), went on an indefinite fast in March and the assembly was dissolved bringing end to agitation.[79][80][81] No fresh election held until Morarji Desai went on indefinite hunger strike in April 1975.[80] The fresh elections were held in June 1975. Chimanbhai Patel formed new party named Kisan Mazdoor Lok Paksh and contested on his own. Congress lost elections which won only 75 seats. Coalition of Congress (O), Jan Sangh, PSP and Lok Dal known as Janata Morcha won 88 seats and Babubhai J. Patel became Chief Minister. Indira Gandhi imposed the emergency in 1975.[80] Janata Morcha government lasted nine months and president's rule imposed in March 1976 following failure of passage of budget in assembly to opposition of coalition partners.[81] Later Congress won elections in December 1976 and Madhav Singh Solanki became Chief Minister.[80][81] A year later Madhav Singh Solanki resigned and again Babubhai Patel led Janata Party formed the government. He shifted his cabinet to Morbi for six months during 1979 Machchhu dam failure disaster which resulted in large casualties.[83]

Janata Morcha government was dismissed and president's rule was imposed in 1980 even though it had majority. Later Madhav Singh Solanki led INC won the election in 1980 and formed the government which completed five years in office. Amarsinh Chaudhary succeeded him in 1985 and headed government till 1989. Solanki again became chief minister until INC lost in 1990 election following Mandal commission protests. Chimanbhai Patel came back to power in March 1990 as the head of a Janata Dal -Bharatiya Janata Party coalition government. Coalition broke just few months after in October 1990 but Chimanbhai Patel managed to retain majority with support of 34 INC legislatures. Later Patel joined the INC and continued till his death in February 1994. Chhabildas Mehta succeeded him and continued till March 1995. In 1994 plague endemic broke out in Surat resulting in 52 deaths.[84]

Following the rise of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) at centre, Keshubhai Patel led BJP won in 1995 assembly election. Keshubhai Patel became the chief minister of Gujarat in March but resigned eight months later as his colleague Shankersinh Vaghela revolted against him. BJP was split as Rashtriya Janata Party was formed by Vaghela who became the Chief Minister by support of INC. Assembly was dissolved in 1998 as INC withdrew its support. BJP returned to power led by Patel in 1998 assembly elections and he became the chief minister again.[85] In 1998, a severe tropical cyclone hit Kandla port and Saurashtra and Kutch regions.[86]

2000–present

Gujarat was hit with a devastating earthquake on 26 January 2001 which claimed a staggering 20,000 lives, injured another 200,000 people and severely affected the lives of 40 million of the population. Patel resigned as chief minister in October 2001 due to his failing health. Allegations of abuse of power, corruption and poor administration; as well as a loss of BJP seats in by-elections and mismanagement of relief works during the aftermath of the 2001 Bhuj earthquake; prompted the BJP's national leadership to seek a new candidate for the office of chief minister. He was replaced by Narendra Modi.[87][88][89][90]

The Gujarat Riots of 2002, was a three-day period of inter-communal violence in Gujarat between the Hindus and Muslims, characterized by mass murder, loot, rape, and destruction of property, affecting thousands of people, mostly Muslims. Though officially classified as a communalist riot, the events of 2002 have been described as a pogrom by many scholars. Scholars studying the 2002 riots state that they were premeditated and constituted a form of ethnic cleansing, and that the state government and law enforcement were complicit in the violence that occurred.[91][92][93][94][95][96][97] However, Special Investigation Team (SIT) appointed by the Supreme Court of India, rejected claims that the state government had not done enough to prevent the riots.[98]

In September 2002, there was a terrorist attack on Akshardham temple complex at Gandhinagar.[99] Modi led BJP won December 2002 election with majority. In 2005 and 2006, Gujarat was affected by floods. In July 2008, a series of 21 bomb blasts hit Ahmedabad, within a span of 70 minutes. 56 people were killed and over 200 people were injured in the attack.[100][101][102] 2009 Gujarat hepatitis outbreak resulted in 49 deaths. In July 2009, more than 130 people died in hooch tragedy.[103]

In 2006, Gujarat became the first state in India to electrify all villages of the state.[104]

Narendra Modi led BJP retained power in 2007 and 2012 assembly elections. Anandiben Patel became the first women Chief Minister of Gujarat on 22 May 2014 as Modi left the position following win in 2014 Indian general election.[105] He was sworn in as the second Prime Minister of Gujarati origin after Morarji Desai in May 2014. Heavy rain in June and July 2015 resulted in widespread flooding in Saurashtra and north Gujarat resulting in more than 150 deaths. The wild life of Gir Forest National Park and adjoining area was also affected.[106][107][108] Starting July 2015, the people of Patidar community carried out demonstrations across the state seeking Other Backward Class status which turned violent on 25 August and 19 September 2015 for brief period.[109] The agitation continued and again turned violent in April 2016.[110] In late 2016, Dalits protested across Gujarat in response to an assault on Dalit men in Una.[111][112] Following heavy rain in July 2017, the state, especially north Gujarat, was affected by the severe flood resulting in more than 200 deaths.[113] In October 2018, a rape incident had triggered the attacks on the Hindi-speaking migrants in Gujarat leading to exodus.[114] In 2019, Vadodara was flooded[115] while there was a fire in a commercial complex at Surat causing death of 22 children.[116] During COVID-19 pandemic, more than 1,00,000 cases and 3100 deaths were reported in Gujarat between March and September 2020.[117] In 2020, the industrial explosions at Dahej and Ahmedabad resulted in five and twelve deaths respectively.[118][119]

The Narendra Modi Stadium of Motera became the world's largest stadium following the renovation in 2021.[120]

Notes

- The Chaulukya dynasty is not to be confused with the Chalukya dynasty.

References

- "Where does history begin?". 18 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Gujarat State Portal "History of Gujarat".

Gujarat : The State took its name from the Gujara, the land of the Gujjars, who ruled the area during the 700's and 800's.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Chaube 1975, pp. 132–136.

- "Modern Gujarat". Mapsofindia.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- Patel, Ambika B. (31 August 1999). "4. Archaeology of Early Historic Gujarat". Iron technology in early historic India a case study of Gujarat (Thesis). Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. pp. 72–105. hdl:10603/71979. Retrieved 14 October 2017 – via Shodhganga.

- Frederick Everard Zeuner (1950). Stone Age and Pleistocene Chronology in Gujarat. Deccan College, Postgraduate and Research Institute.

- "Antiquity Journal". antiquity.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Malik, S. C. (1966). "The Late Stone Age Industries from Excavated Sites in Gujarat, India". Artibus Asiae. 28 (2/3): 162–174. doi:10.2307/3249352. JSTOR 3249352.

- K., Krishnan; S. V., Rajesh (2015). Dr., Shakirullah; Young, Ruth (eds.). "Scenario of Chalcolithic Site Surveys in Gujarat". Pakistan Heritage. 7: 1–34 – via Academia.edu.

- Ajithprasad, P (1 January 2002). "The Mesolithic culture in the Orsang Valley, Gujarat". Mesolithic India: 154–189.

- Raj Pruthi (1 January 2004). Prehistory and Harappan Civilization. APH Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 978-81-7648-581-4.

- Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. p. 78.

- Witzel, Michael (October 1999). "Early Sources for South Asian Substrate Languages" (PDF). Mother Tongue: 25.

- Witzel, Michael (2019). "Early 'Aryans' and their neighbors outside and inside India". Journal of Biosciences. 44 (3): 5. doi:10.1007/s12038-019-9881-7. PMID 31389347. S2CID 195804491.

- Varma, Supriya (11 August 2016). "Villages abandoned: The case for mobile pastoralism in post-Harappan Gujarat". Studies in History. 7 (2): 279–300. doi:10.1177/025764309100700206. S2CID 161465765.

- Kathleen D. Morrison; Laura L. Junker (5 December 2002). Forager-Traders in South and Southeast Asia: Long-Term Histories. Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-0-521-01636-0.

- Sankalia, Hasmukh D. (1949). Studies in the Historical and Cultural Geography of Gujarat. Deccan College. p. 162.

- F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (7 September 1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2.

- Kumaran, R. N. (2014). "Second urbanization in Gujarat". Current Science. 107 (4): 580–588. ISSN 0011-3891. JSTOR 24103529.

- Salomon, Richard (1998), Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages, Oxford University Press, pp. 194, 199–200 with footnote 2, ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3

- Singh, Upinder (2016). The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archeology. SAGE. p. 277.

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [Fourth Edition: 1966]. Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 42–43. ISBN 81-208-0405-8.

- Virji, Krishnakumari J. (1952). Ancient History of Saurashtra. Konkan Institute of Arts and Sciences. p. 2.

- Sharma, Tej Ram (1978). Personal and Geographical Names in Gupta Inscriptions. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 299–300.

- Sankalia 1949, p. 9.

- Fuller, Paul (2005). The Notion of Diṭṭhi in Theravāda Buddhism: the Point of View. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 16.

- Sircar, D. C. (1966). Indian Epigraphical Glossary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 316.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2016). A History of India. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-138-96115-9.

- Narain, A. K. (1957). The Indo-Greeks. Clarendon Press. p. 93.

- Bhandarkar, Ramkrishna Gopal (1896). Campbell, James M. (ed.). "Early History of the Dakhan Down to the Mahomedan Conquest". Gazetter of the Bombay Presidency: History of the Konkan Dakhan and Southern Maratha Country. Government Central Press. I (II): 174.

- Trade And Trade Routes in Ancient India von Moti Chandra page: 99

- Sharma 2005, p. 275-276.

- Sharma, R. S. (2005). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-19-908786-0.

- Sankalia 1949, p. 10.

- "Rani-ki-Vav (the Queen's Stepwell) at Patan, Gujarat". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Ancient India by Ramesh Chandra Majumdar p. 366

- History, Religion and Culture of India, by S. Gajrani p.32

- "CNG: eAuction 343. INDIA, Post-Gupta (Gujura Confederacy). Gujuras of Sindh. Circa AD 570-712. AR Drachm (25mm, 3.84 g, 9h)". www.cngcoins.com.

- Rose, Horace Arthur; Ibbetson (1990). Glossary of the Tribes and Castes of the Punjab and North West Frontier Province. Asian Educational Services. p. 300. ISBN 978-81-206-0505-3.

- Misra, Satish Chandra (1982). The Rise of Muslim Power in Gujarat: A History of Gujarat from 1298 to 1442. Munshiram Manoharlal.

- "Historic City of Ahmadabad". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- Hooja 2006, pp. 450–452.

- Sharma 1954, pp. 18.

- Sudipta Mitra (2005). Gir Forest and the Saga of the Asiatic Lion. Indus Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-7387-183-2.

- Commissariat 1938, Volume I, p. 506-507.

- Commissariat 1938, Volume I, p. 508-509.

- Commissariat 1938, Volume I, p. 510-512.

- Commissariat 1938, Volume I, p. 520-521.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 1.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 3.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 4-5.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 5.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 52.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 9-10, 48.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 108.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 110.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 115-116.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 121.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 125.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 162.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 171-172.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 180.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 187.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 188.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 189.

- Commissariat 1957, Volume II, p. 199-200.

- Jaswant Lal Mehta (1 January 2005). Advanced Study in the History of Modern India 1707-1813. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-1-932705-54-6.

- Campbell 1896, p. 266-347.

- Osekhara Bandyopoadhyoa Ya; Śekhara Bandyopādhyāẏa (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- A., Nadri, Ghulam (2009). Eighteenth-century Gujarat : the dynamics of its political economy, 1750–1800. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004172029. OCLC 568402132.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - WINGS Birding Tours to India: the West – Gujarat and the Rann of Kutch – Itinerary Archived 30 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Wingsbirds.com (14 December 2011). Retrieved on 28 July 2013.

- Rai, Rajesh; Reeves, Peter (2009). The South Asian diaspora transnational networks and changing identities. London: Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-203-89235-0. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- Petersen, Eskild; Chen, Lin Hwei; Schlagenhauf-Lawlor, Patricia (2017). Infectious Diseases: A Geographic Guide. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 8. ISBN 9781119085737.

- Wood, John R. (1984). "British versus Princely Legacies and the Political Integration of Gujarat". The Journal of Asian Studies. 44 (1): 65–99. doi:10.2307/2056747. JSTOR 2056747.

- Laskar, Rezaul (10 August 2011). "Pak Pilot's Remorse for 1965 Shooting of Indian Plane". Outlook. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- "Pakistan pilot's 'remorse' for 1965 shooting down". BBC. 10 August 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- Ornit Shani (12 July 2007). Communalism, Caste and Hindu Nationalism: The Violence in Gujarat. Cambridge University Press. pp. 161–164. ISBN 978-0-521-68369-2. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Kalia, Ravi (2004). Gandhinagar: Building National Identity in Postcolonial India. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 26, 33, 36, 37, 115. ISBN 9781570035449.

- Shah, Ghanshyam (20 December 2007). "Pulse of the people". India Today. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Krishna, Ananth V. (2011). India Since Independence: Making Sense of Indian Politics. Pearson Education India. p. 117. ISBN 9788131734650. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Dhar, P. N. (2000). "Excerpted from 'Indira Gandhi, the "emergency", and Indian democracy' published in Business Standard". Business Standard India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195648997. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- jain, Arun Kumar (1978). Political Science. FK Publication. p. 114. ISBN 9788189611866. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Gujarat ex-CM Babubhai Patel passes away". The Times of India. Gandhinagar. 20 December 2002. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. pp. 542–543. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Bapa Keshubhai Patel remains man of the masses". DNA. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- World Ship Society (2000). Marine News. World Ship Society. p. 54. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- Aditi Phadnis (2009). Business Standard Political Profiles of Cabals and Kings. Business Standard Books. pp. 116–21. ISBN 978-81-905735-4-2. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Bunsha, Dionne (13 October 2001). "A new oarsman". Frontline. India. Archived from the original on 23 January 2002. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Venkatesan, V. (13 October 2001). "A pracharak as Chief Minister". Frontline. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "Death for 11, life sentence for 20 in Godhra train burning case". The Times of India. 1 March 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- Nussbaum 2008, p. 50-51.

- Bobbio, Tommaso (2012). "Making Gujarat Vibrant: Hindutva, development and the rise of subnationalism in India". Third World Quarterly. 33 (4): 657–672. doi:10.1080/01436597.2012.657423. S2CID 154422056. (subscription required)

- Shani 2007b, pp. 168–173.

- Buncombe, Andrew (19 September 2011). "A rebirth dogged by controversy". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (June 2013). "Gujarat Elections: The Sub-Text of Modi's 'Hattrick'—High Tech Populism and the 'Neo-middle Class'". Studies in Indian Politics. 1 (1): 79–95. doi:10.1177/2321023013482789. S2CID 154404089.Jaffrelot, Christophe (June 2013). "Gujarat Elections: The Sub-Text of Modi's 'Hattrick'—High Tech Populism and the 'Neo-middle Class'". Studies in Indian Politics. 1 (1): 79–95. doi:10.1177/2321023013482789. S2CID 154404089.

- Pandey, Gyanendra (November 2005). Routine violence: nations, fragments, histories. Stanford University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-8047-5264-0.

- Gupta, Dipankar (2011). Justice before Reconciliation: Negotiating a 'New Normal' in Post-riot Mumbai and Ahmedabad. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-415-61254-8.

- "How SIT report on Gujarat riots exonerates Modi". CNN-IBN. 11 November 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2013.

- "India riots: Court convicts 32 over Gujarat killings". BBC News. 29 August 2012.

- "Ahmedabad blasts claim two more victims". The Hindu. 1 August 2008. Archived from the original on 10 August 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "Gujarat police release three sketches". The Hindu. Kasturi & Sons Ltd. 6 August 2008. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Death toll in Ahmedabad serial blasts rises to 55". Khabrein.info. 1 August 2008. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Gujarat hooch tragedy: Death toll rises to 136

- "Gujarat becomes first to electrify all villages". The Economic Times.

- "Anandiben Patel: Gujarat's First Woman Chief Minister". NDTV.com.

- Sonawane, Vishakha (26 June 2015). "Heavy Rains in India: 70 Dead in Gujarat, Flood Alert in Jammu And Kashmir". International Business Times. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "5 Lions Found Dead in Gujarat After Heavy Rain Leads to Flooding". NDTV. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Gujarat floods: More than 1,500 people evacuated after water level of Sabarmati rises dramatically – Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dna. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- "Agitation for reservation by Patel community puts BJP government in bind". timesofindia-economictimes. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Patidar reservation protests: Surat youth commits suicide". Scroll.in. 18 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "4 Dalits stripped, beaten up for skinning dead cow". The Times of India. 13 July 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- "Old enmity behind flogging of Dalit youths in Una: Fact-finding team". Hindustan Times. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- "Gujarat Floods: Number of Deaths Increases To 218 As More Bodies Found". NDTV. 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Sharon, Meghdoot (7 October 2018). "UP, Bihar Migrants Flee Gujarat After 'Rape Backlash' Triggers Attacks; 342 Arrested". News18. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Cloudburst in Vadodara: 424 mm Rainfall in Six Hours; City Flooded, Schools Closed". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- "Number Of Deaths In Surat Coaching Centre Fire Rises To 22". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "Gujarats coronavirus caseload crosses one lakh mark". outlookindia.com. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- "12 killed in Gujarat after blast in factory leads to textile godown collapse". The Indian Express. 5 November 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- "At least 5 dead, 50 injured in blast at chemical factory in Gujarat's Dahej". The Indian Express. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Langa, Mahesh (8 March 2021). "Motera cricket stadium, world's largest, named after Modi". The Hindu.

Bibliography

- Commissariat, M.S. (1938). A History of Gujarat. Vol. I From AD 1297-8 to AD 1573. Longmans, Green & Co. Ltd.

- Commissariat, M.S. (1957). A History of Gujarat. Vol. II The Mughal Period: From 1573 to 1758. Orient Longmans.

- Campbell, James Macnabb (1896). "Chapter III. MUGHAL VICEROYS. (A.D. 1573–1758)". In James Macnabb Campbell (ed.). History of Gujarát. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Vol. I. Part II. Musalmán Gujarát. (A.D. 1297–1760.). The Government Central Press. pp. 266–347.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Nussbaum, Martha Craven (2008). The Clash Within: Democracy, Religious Violence, and India's Future. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03059-6.

- Shani, Ornit (2007). Communalism, Caste and Hindu Nationalism: The Violence in Gujarat. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-72753-2.

Further reading

- Chaube, J. (1975). History of Gujarat Kingdom, 1458-1537. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 9780883865736.

- Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-0890-6.

- Sharma, Gopi Nath (1954). Mewar & the Mughal Emperors (1526-1707 A.D.). S.L. Agarwala.

- Edalji Dosabhai. A History of Gujarat (1986) 379 pp. full text online free Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Padmanābha, ., & Bhatnagar, V. S. (1991). Kanhadade Prabandha: India's greatest patriotic saga of medieval times : Padmanābha's epic account of Kānhaḍade. New Delhi: Voice of India.

- Yazdani, Kaveh. India, Modernity and the Great Divergence: Mysore and Gujarat (17th to 19th C. (Leiden: Brill, 2017. 669 pp. ISBN 978-90-04-33079-5 online review