Maastrichtian dialect

Maastrichtian (Limburgish: Mestreechs [məˈstʀeːçs]) or Maastrichtian Limburgish (Limburgish: Mestreechs-Limbörgs [məˌstʀeːçsˈlimbœʀ(ə)çs]) is the dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Dutch city of Maastricht alongside the Dutch language (with which it is not mutually intelligible). In terms of speakers, it is the most widespread variant of Limburgish, and it is a tonal one. Like many of the Limburgish dialects spoken in neighbouring Belgian Limburg,[2] Maastrichtian retained many Gallo-Romance (French and Walloon) influences in its vocabulary.[3]

| Maastrichtian | |

|---|---|

| Mestreechs (sometimes Mestreechs-Limbörgs or colloquially Dialek, Plat) | |

| Pronunciation | [məˈstʀeːçs] |

| Native to | the Netherlands |

| Region | City of Maastricht |

Native speakers | (undated figure of 60,000) |

Indo-European

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Limburg, Netherlands: Recognised as regional language as a variant of Limburgish. |

| Regulated by | Veldeke-Krink Mestreech |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

The French influence can additionally be attributed to the historical importance of French with the cultural elite and educational systems as well as the historical immigration of Walloon labourers to the city. Despite being a specific variant of Limburgish, Maastrichtian remains mutually intelligible with other Limburgish variants, especially those of surrounding municipalities.

Whilst Maastrichtian is still widely spoken, regardless of social level, research has shown that it is suffering from a degree of dialect loss amongst younger generations. That is the case in dwindling of speakers but also in development of the dialect (dialect levelling) towards Standard Dutch (like the loss of local words and grammar).[1]

Geographic distribution, social status and sociolects

Maatrichtian being a city dialect, the terminology "Maastrichtian" (Mestreechs) is practically limited to the municipal borders, with the exception of some places within the Maastrichtian municipality where the spoken dialects are in fact not Maastrichtian. These exceptions are previously separate villages and/or municipalities that have merged with the municipality of Maastricht namely Amby, Borgharen, Heer and Itteren.

The social status of Maastrichtian speakers is determined by the type of sociolect spoken by a certain person, with a division between Short Maastrichtian or Standard Maastrichtian[4] (Kort Mestreechs, Standaardmestreechs) and Long/Stretched Maastrichtian (Laank Mestreechs). Short Maastrichtian is generally considered to be spoken by the upper and middle classes, whilst Long Maastrichtian is considered to be spoken by the working class.

A particular feature of Maastrichtian is that it gives its speakers a certain prestige.[5] Research of the dialect showed that people talking the "purest" form of Maastrichtian, i.e. the Short Maastrichtian (Kort Mestreechs) sociolect, were perceived by others to be the well-educated ones.

Written Maastrichtian

The oldest known and preserved text in Maastrichtian dates from the 18th century. This text named Sermoen euver de Weurd Inter omnes Linguas nulla Mosa Trajestensi prastantior gehauwe in Mastreeg was presumably written for one of the carnival celebrations and incites people to learn Maastrichtian. As from the 19th century there are more written texts in Maastrichtian, again mostly oriented towards these carnival celebrations. Nowadays however, many other sources display written Maastrichtian, including song texts not written for carnival as well as books, poems, street signs etc.

Standardisation and official spelling

In 1999, the municipal government recognised a standardised spelling of Maastrichtian made by Pol Brounts and Phil Dumoulin as the official spelling of the dialect.[4]

Dictionaries

- Aarts, F. (2005). Dictionairke vaan 't Mestreechs. (2nd ed.). Maastricht, the Netherlands: Stichting Onderweg.

- Brounts P., Chambille G., Kurris J., Minis T., Paulissen H. & Simais M. (2004). De Nuie Mestreechsen Dictionair. Maastricht, the Netherlands: Veldeke-Krink Mestreech.

Other literature on Maastrichtian

- Aarts, F. (2001). Mestreechs. Eus Moojertoal: 'ne Besjrijving vaan 't dialek vaan Meestreech. Maastricht, the Netherlands: Veldeke-Krink.

- Aarts, F. (2009). 't Verhaol vaan eus Taol. Maastricht, the Netherlands: Stichting Onderweg.

- Aarts, F. (2019). Liergaank Mestreechs: 'ne Cursus euver de Mestreechter Taol. Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Local anthem

In 2002, the municipal government officially adopted a local anthem (Mestreechs Volksleed) composed by lyrics in Maastrichtian. The theme had originally been written by Alfons Olterdissen (1865–1923) as finishing stanza of the Maastrichtian opera "Trijn de Begijn" of 1910.[6] There are claims that the anthem actually originates from "Pe-al nostru steag e scris Unire" by the Romanian composer Ciprian Porumbescu.[7]

| Maastrichtian municipal anthem (Mestreechs Volksleed) (2002) |

|---|

|

Wikimedia

- Wikipedia: Maastrichtian is included in the Limburgish Wikipedia. Since there are only standardised 'variants' of Limburgish but no widely accepted/recognised standardised Limburgish itself, each article is tagged as being written in a certain variant of the language. All articles in Maastrichtian can be found here.

- Wiktionary: For an overview of some Maastrichtian dialect specific words, their English translations and their origins proceed to this Wiktionary category.

Phonology

As many other Limburgish dialects, the Maastrichtian dialect features a distinction between Accent 1 and Accent 2, limited to stressed syllables. The former can be analyzed as lexically toneless, whereas the latter as an underlying high tone. Phonetically, syllables with Accent 2 are considerably longer. An example of a minimal pair is /ˈspøːlə/ 'to rinse' vs. /ˈspøː˦lə/ 'to play'. The difference is not marked in the orthography, so that both of those words are spelled speule.[8]

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | (ɲ) | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | (tʃ) | k | (ʔ) | |

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | (ʃ) | x | ||

| voiced | v | z | (ʒ) | ɣ | ɦ | ||

| Liquid | l | ʀ | |||||

| Approximant | w | j | |||||

- /m, p, b/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental.[9]

- /w/ is realized as a bilabial approximant [β̞] in the onset and as labio-velar [w] in the coda.[10] In this article, both are transcribed with ⟨w⟩, following the recommendations of Carlos Gussenhoven regarding transcribing the corresponding Standard Dutch phone.[11]

- [ɲ, tʃ, ʃ, ʒ] can be analysed as /nj, tj, sj, zj/.[10]

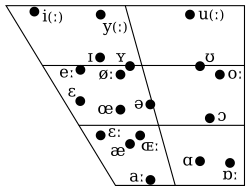

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | iː | y | yː | u | uː | ||

| Close-mid | ɪ | eː | ʏ | øː | ə | ʊ | oː | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɛː | œ | (œː) | ɔ | (ɔː) | ||

| Open | æ | ɶː | aː | ɑ | ɒː | |||

| Diphthongs | ɛj œj ɔw | |||||||

- The phonetic value of the symbol ⟨ʏ⟩ is far removed from its canonical IPA value [ʏ], being a close-mid central vowel: [ɵ]. All of the vowels labelled as close-mid in the table are phonetically close-mid, including /ɪ/ and /ʊ/.[13]

- The long mid monophthongs [eː, øː, oː, œː, ɔː] are monophthongal when combined with Accent 2. When combined with Accent 1, they are all diphthongal: [eɪ, øʏ, oʊ, œj, ɔw]. Phonologically, the first three are close-mid monophthongs /eː, øː, oː/, whereas the latter two are diphthongs /œj, ɔw/.[14] Elsewhere in the article, the diphthongality of the first three is ignored and they are always transcribed with ⟨eː, øː, oː⟩.

- The open-mid front [ɛː] is diphthongized to [ɛj] in words with Accent 2 when it is a realization of the underlying /ɛj/. The underlying /ɛː/ does not participate in tonal distinction, and neither do /ɶː/ and /ɒː/.[15]

- /ɛː/ has mostly merged with /eː/ under the influence of Standard Dutch. A phonemic /ɛː/ appears in French loanwords such as tête /tɛːt/ 'brawn'. Most phonetic instances of [ɛː] in the dialect are monophthongized /ɛj/.

- The open-mid [œː, ɔː] contrast not only with the close-mid [øː, oː] but also with the open [ɶː, ɒː] in (near)-minimal pairs such as eus [øːs] 'ours' vs. struis [stʀœːs˦] vs. käös [kɶːs] 'choice'.[16]

- /ə/ occurs only in unstressed syllables.[17]

Orthography

| Consonants | ||||||||||||||||||||

| b | ch | d | f | g | gk | h | j | k | l | m | n | ng | p | r | s | sj | t | v | w | z |

| Vowels (both monophthongs and diphthongs) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | aa | aaj | aj | ao | aoj | äö | äöj | aj | au | aw | e | è | ee | ei | ej | eu | ew | i | ie | iew | o | ó | ö | oe | oo | ooj | ou | u | ui | uu |

Vocabulary

Maastrichtian contains many specific words ample or not used in other Limburgish dialects some being creolisations/"limburgisations" of Dutch, French and German words while others cannot be directly subscribed to one of these languages.

(Historical) Vocabulary influences from other languages

Maastrichtian vocabulary, as the language family it belongs to suggests, is based on the Germanic languages (apart from the Limburgish language family this also includes varying degrees of influence from both archaic and modern Dutch and German). However, what sets Maastrichtian apart from other variants of Limburgish is its relatively strong influences from French. This is not only because of geographic closeness of a Francophone region (namely Wallonia) to Maastricht but also because of French being the predominant spoken language of the Maastrichtian cultural elite and the higher secondary educational system of the region in the past. Some examples:

Francophone influence

| English | Dutch | French | Maastrichtian [3][4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| to advance | vooruitkomen | avancer | avvencere |

| bracelet | armband | bracelet | brazzelèt |

| errand | boodschap | commission | kemissie |

| jealous | jaloers | jaloux | zjelous |

| to remember | (zich) herinneren | se rappeler | (ziech) rappelere |

| washbasin | wastafel | lavabo | lavvabo |

Germanophone influence

| English | Dutch | German | Maastrichtian [3][4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| bag | zak, tas | Tüte | tuut |

| ham | ham | Schinken | sjink |

| liquorice candy | drop | Lakritze | krissie |

| plate | bord | Teller | teleur |

| ready, done | klaar | fertig | veerdeg |

| swing (for children) | schommel | Schaukel | sjógkel |

Other examples of Maastrichtian vocabulary

Some examples of specific Maastrichtian vocabulary:

| English | Dutch | French | German | Maastrichtian [3] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| approximately, roughly | ongeveer | appoximativement, environ | ungefähr | naoventrint | |

| bag | tas | sac | Tasche | kalbas | |

| completely | helemaal, gans | tout à fait | ganz | gans | (historically) Common in Germanic languages |

| frame (of doors and windows) | lijst | cadre (or chambranle) | Rahmen | sjabrang | |

| grandmother / grandfather | grootmoeder / grootvader | grand-mère / grand-père | Großmutter / Großvater | bomma(ma) / bompa(pa) | |

| sieve | vergiet | passoire | Sieb | zeiboar (sometimes written zeijboar) | |

| where? | waar? | où? | wo? | boe? |

Expressions and Titles

Some examples of Maastrichtian expressions:

| Maastrichtian Expression | Meaning (Approx.) | Notes [3] |

|---|---|---|

| Neet breid meh laank | Literally "Not broad but long". Commonly used to indicate the characteristic of the Maastrichtian dialect to "stretch" vowels (in speech and writing). The word laank (long) is the example in this case whereas it would be written as either lank or lang in other variants of Limburgish and lang in Dutch. | |

| Noondezju [3] | A minor swear word and /or an expression of surprise | From Eastern Walloon "nondidju", meaning "(in) name of God" |

| Preuvenemint | Name of an annual culinary festival held in Maastricht | A contraction of the Maastrichtian words preuve (to taste) and evenemint (event) |

References

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999:155)

- Rob Belemans & Benny Keulen, Taal in stad en land: Belgisch-Limburgs, 2004

- Brounts P.; Chambille G.; Kurris J.; Minis T.; Paulissen H.; Simais M. (2004). "Veldeke Krink Mestreech: Nuie Mestreechsen Dictionair". Veldeke-Krink Mestreech. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- Aarts, F. (2009). "t Verhaol vaan eus Taol". Stichting Onderweg.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - Muenstermann, H. (1989). Dialect loss in Maastricht. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9789067652704. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- Municipality of Maastricht (2008). "Municipality of Maastricht: Maastrichts Volkslied". N.A. Maastricht. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- Roca, George (28 January 2016). "Pe-al vostru steag e scris Unire!?". Gândacul de Colorado (in Romanian).

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), p. 162.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), p. 155.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), p. 156.

- Gussenhoven (2007), pp. 336–337.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), pp. 158–159, 161–162.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), p. 159.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), pp. 158–159, 161–162, 165.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), pp. 158–159, 161–162, 164–165.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), pp. 161–162.

- Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), p. 158.

Bibliography

- Gussenhoven, Carlos; Aarts, Flor (1999), "The dialect of Maastricht" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, University of Nijmegen, Centre for Language Studies, 29 (2): 155–166, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006526, S2CID 145782045

- Gussenhoven, Carlos (2007). "Wat is de beste transcriptie voor het Nederlands?" (PDF) (in Dutch). Nijmegen: Radboud University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

Further reading

- van der Wijngaard, Ton (1999), "Maastricht" (PDF), in Kruijsen, Joep; van der Sijs, Nicoline (eds.), Honderd Jaar Stadstaal, Uitgeverij Contact, pp. 233–249