Lohara dynasty

The Lohar dynasty were a Kashmiri Hindu dynasty which ruled over Kashmir and surrounding regions in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, for more than 3 centuries between 1003 CE and approximately 1320 CE. The early history of the dynasty was described in the Rajatarangini (Chronicle of Kings), a work written by Kalhana in the mid-12th century and upon which many and perhaps all studies of the first 150 years of the dynasty depend. Subsequent accounts, which provide information up to and beyond the end of the dynasty come from Jonarāja and Śrīvara. The later rulers of the dynasty were weak: internecine fighting and corruption was endemic during this period, with only brief years of respite, making the dynasty vulnerable to the growth of Islamic conquests in the region.[2]

Lohar dynasty | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1003 CE–1320 CE | |||||||||

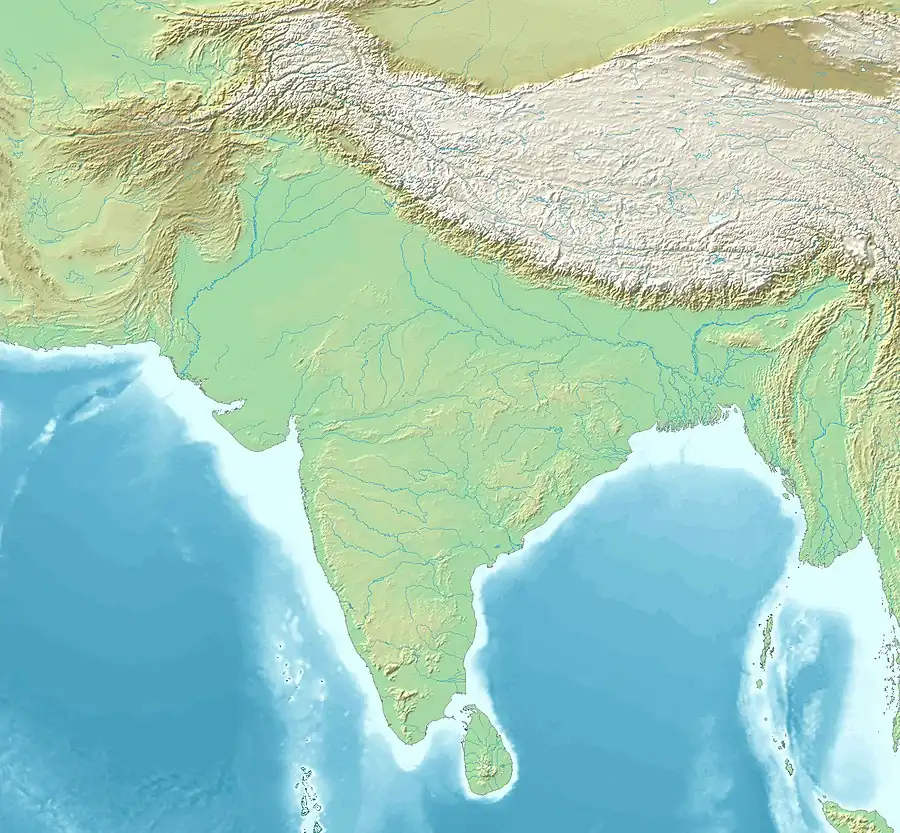

◁ ▷ Location of the Lohara dynasty and neighbouring polities circa 1175 CE. The Lohara dynasty resisted Muslim rule for three more centuries.[1] | |||||||||

| Capital | Srinagar | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• 1003 – 1028 CE | Sangramaraja | ||||||||

• 1301 – 1320 CE | Suhadeva | ||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||

• Established | 1003 CE | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1320 CE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Afghanistan India Pakistan | ||||||||

Origins

According to 12th century text Rajatarangini translated by Sir Marc Aurel Stein, the family of the chiefs of Lohara were from Khasa tribe.[3][4] The original seat of the Lohar dynasty was a hill-fortress called Loharkotta. Stein locates it in the Pir Panjal range of mountains, on a trade route between western Punjab and Kashmir in the present day Poonch district. The kingdom of Lohar was centred around a group of large villages collectively known as Lohrin in a valley, and probably extended into neighbouring valleys.[5]

Didda, a daughter of the king of Lohar called Simharāja, had married the king of Kashmir, Kshemgupta, thus uniting the two areas. Compared to other societies of the period, women in Kashmir were held in high regard[6] and when Kshemgupta died in 958, Didda assumed power as Regent for her young son, Abhimanyu II. Upon the death of Abhimanyu in 972 she performed the same office for his sons, Nandigupta, Tribhuvanagupta, and Bhimagupta, respectively. She killed each of these grandchildren in turn. As Regent she effectively had sole power over the kingdom, and with the killing by torture of Bhimagupta in 980 she became ruler in her own right.[7][8]

Didda subsequently adopted a nephew, Samgrāmarāja, to be her heir in Kashmir but left the rule of Lohar to Vigraharāja, who was either another nephew or perhaps one of her brothers. From this decision arose the Lohara dynasty of Kashmir, although Vigraharāja even during her lifetime made attempts to assert his right to that area as well as Lohar.[7] What was to follow was around three centuries of "endless rebellions and other internal troubles".[9]

First Lohar dynasty

Samgrāmarāja

Samgrāmarāja is considered as the founder of the Lohar dynasty.[13]

Samgrāmarāja was able to repulse several attacks of Mahmud of Ghazni against Kashmir, and he also supported ruler Trilochanapala against Muslim attacks.[13]

The reign of Samgrāmarāja between 1003 and June or July 1028 was largely characterised by the actions of those in his court, who preyed on his subjects to satisfy their own greed, and by the role of the prime minister, Tunga. The latter was a former herdsman who had become the lover of Didda and was her prime minister. He had wielded much power in working with Didda to assert her dominance over the kingdom and he continued to use that power after her death. Samgrāmarāja was afraid of him and for many years allowed him to have his way. Indeed, it was Tunga who appointed many of the corrupt officials who proceeded to extract significant amounts of wealth from the kingdom's subjects. These appointees, and their actions, made Tunga unpopular, and his age may well have contributed to his increasing inability to deal with challenges from opponents within and without the court. Samgrāmarāja quietly supported the plots to remove the minister, and eventually Tunga was murdered; however, this did little to improve matters either in the court or the country as his death caused an influx of royal favourites who were no less corrupt than those who had been appointed by him.[14][15]

Harirāja and Ananta

Samgrāmarāja's son, Harirāja, succeeded him but reigned for only 22 days before dying and being succeeded in turn by another son, Ananta. It is possible that Harirāja was killed by his mother, Shrilakhā, who may have been desirous of holding power herself but was ultimately thwarted in that scheme by those protecting her children.[14][16] It was around this time that Vigraharāja attempted once more to take control of Kashmir, taking an army to do battle near to the capital at Srinagar and being killed in defeat.[7]

The period of rule by Ananta was characterised by royal profligacy; he accumulated debts so large that it necessitated the pawning of the royal diadem, although when his queen, Sūryamatī, intervened the situation was improved. She was able to settle the debts incurred by her husband by use of her own resources and she also oversaw the appointment of ministers with ability in order to stabilise the government.[14] In 1063, she forced Ananta to abdicate in favour of their son, Kalaśa. This was probably in order to preserve the dynasty but the strategy proved not to be successful because of Kalaśa's own unsuitability. It was then arranged that Ananta was effective king even though his son held the title.[17]

Kalaśa, Utkarsa and Harsa

Kalaśa was king until 1089. Another weak-willed man, who involved himself in an incestuous relationship with his daughter, Kalaśa was dominated by those surrounding him at court and spent little time on matters of government until his later years. He freed himself from the effective rule of his father in 1076, causing Ananta to leave the capital along with many loyal courtiers and then laying siege to them in their new abode at Vijayesvara. On the verge of being pushed into exile, and faced with a wife who even at this stage doted on her son, Ananta committed suicide in 1081. It was after this that Kalaśa reformed his licentious ways and began to govern responsibly, as well as operating a foreign policy that improved the influence which the dynasty held over surrounding hill tribes.[14][19]

Kalaśa experienced difficulties with his oldest son, Harsa, who felt that the allowance granted by his father was insufficient for his extravagant tastes. Harsa plotted to kill Kalaśa, was found out and eventually imprisoned. His position as heir to the throne was given instead to his younger brother, Utkarsa, who was already ruler of Lohar.[nb 1] The strain of dealing with Harsa caused Kalaśa to revert to his previous dissolute lifestyle and Stein believes that this contributed to his death in 1089. Despite being removed as heir, Hasan believes Harsa did immediately succeed his father[20] but Stein says that Utkarsa succeeded and that Harsa remained in prison. With the accession of Utkarsa to the throne of Kashmir came the reunification of that kingdom with Lohar, as they had been during the reign of Didda. It is at this point that the fortress became the dynastic seat.[7][17][21]

Hasan and Stein agree that Harsa became king in 1089. Utkarsa was disliked and soon deposed, with a half-brother called Vijayamalla[nb 2] supporting Harsa and being at the forefront of the rebellion against the king.[21] Utkarsa was in his turn imprisoned and he committed suicide.[23]

Harsa

_1089-1101_CE.jpg.webp)

Harsa had been a cultured man with much to offer his people but became as prone to the influence of certain favourites and as corrupt, cruel and profligate as his predecessors. He, too, indulged in incest and Stein has said that he was

undoubtedly the most striking figure among the later Hindu rulers of Kashmir. His many and varied attainments and the strange contrasts in his character must have greatly exercised the mind of his contemporaries ... Cruelty and kindheartedness, liberality and greed, violent selfwilledness and reckless supineness, cunning and want of thought – these and other apparently irreconcilable features in turn display themselves in Harsa’s chequered life."[23]

After an initial period during which the economic fortunes of the kingdom appear to have improved, as evidenced by the issue of gold and silver coinage, the situation deteriorated and even night soil was taxed, while temples were looted to further raise money to fund his failed military ventures and his indulgent lifestyle. All but two of the statues of Buddha in his kingdom were destroyed during his rule. Even in 1099, when his kingdom was ravaged by plague, flood and famine, as well as by lawlessness on a large scale, Harsa continued to plunder the wealth of his subjects.[25]

Harsa faced numerous challenges to his reign and he executed many of his relatives, some but not all of whom had been among the challengers.[22] He conducted campaigns in the east of the valley to wrest control of land back from feudatory landlords, who were known as dāmaras, and in 1101 they murdered him.[20][26] Stein describes that while Harsa's rule seemed at first to have "secured a period of consolidation and of prosperous peace ... [it] had subsequently fallen a victim to his own Nero-like propensities".[27]

Second Lohara dynasty

Uccala

Uchchala, who was from a side-branch of the Lohara royal line, succeeded to the throne and reigned for a decade. He and his younger brother, Sussala, had been spotted by Harsa as pretenders to his crown during the unrest and in 1100 had been forced to flee. The move did them no harm as it increased their status among the dāmaras: if Harsa wanted the brothers dead then that was all the more reason to rally around them. It was as a consequence of this that Uccala was able to mount armed attacks on Harsa, as in 1101, which although initially unsuccessful did eventually achieve their aim as those closest to Harsa deserted him.[29]

The two kingdoms of Kashmir and Lohara were again split at the time of Uccala's accession, with Uccala ceding rule over Lohara to Sussala in an attempt to head off any potential challenge from his ambitious brother.[30][31] The rule of Uccala was largely a victim of inherited circumstances, and in particular the fact that the power of the dāmaras which had caused the downfall of Harsa was also a strength that could now be turned on him. He was unable to stabilise the penurious kingdom, either economically or in terms of authority, although it was not due to any lack of capability on his part and he did succeed in forming an alliance with the most powerful dāmara, Gargacandra. He was, in the opinion of Hasan, an able and conscientious ruler.[20][27] Stein has explained the method adopted to counter the dāmaras:

By fomenting among them jealousy and mutual suspicion, he secured the murder or exile of their most influential leaders, without himself incurring the odium. Then, reassured in his own position, he openly turned upon the Dāmaras and forced them into disarmament and submission.[31]

Radda, Salhana and Sussala

The downfall of Uccala came in December 1111 as a result a conspiracy, and after a prior attempt by Sussala to overthrow him. Sussala was not in the vicinity at the time that Uccala was murdered but within days had attempted a hazardous winter crossing over the mountains to Srinagar. Foiled by the winter weather on this occasion, he was able a few months later to venture once more and he proceeded to take control of Kashmir from a half-brother, Salhana.[30] Salhana had himself taken the throne after the briefest of reigns by Radda, one of the leaders of the conspiracy against Uccala, whose rule lasted a single day. It was Gargacandra who organised the defeat of the conspirators and it was he who installed Salhana, using him as a puppet for the violent four months until the arrival of Sussala, a period which Kalhana described as a "long evil dream".[27]

Gargacandra had again been kingmaker in allying with Sussala, whom Stein believes to have been "personally brave, but rash, cruel and inconsiderate" and whose rule was, "practically one long and disastrous struggle with the irrepressible Dāmaras and with dangerous pretenders."[32] As part of their alliance, Gargacandra arranged the marriage of two of his daughters, one to Sussala and one to Sussala's son, Jayasimha.[33] Having turned on Gargacandra and defeated him,[nb 3] Sussala was faced by other dāmaras who in the absence of the once-dominant kingmaker saw an opportunity to challenge the king. They found a potential candidate for the throne in Bhikşācara, a grandson of Harsa. and managed to install him briefly in 1120 when their numbers had swollen sufficiently in opposition to the brutally oppressive measures adopted by Sussala. The restoration of Harsa's dynastic line did not last for long: a fightback by Sussala, who had decamped in defeat from Srinagar to Lohar, resulted in the pretender being deposed around six months later, in early 1121. Thereafter, Sussala resumed his oppression and treated the wealth of his people as being his own. He also imprisoned troublesome members of his own family but, like others before him, he was unable to control the lawlessness among the feudatory chiefs. While squabbling among the dāmaras had assisted him in regaining the throne, he found himself frequently under siege upon his return as they sought to maintain a state of near anarchy in which they could profit for themselves.[20][30][32]

In 1123, during a period of intense pressure from besieging dāmaras and while mourning the death of one of his wives, Sussala abdicated in favour of his son, Jayasimha, He soon changed his mind and although Jayasimha was formally crowned as king it was Sussala who continued to govern.[35]

Jayasimha

Jayasimha succeeded his father in 1128 during a period when there was open rebellion. A plot intended to assert authority had backfired on Sussala and caused his death. Jayasimha was not a forceful character but he did nonetheless manage to bring about both peace and a degree of economic well-being during his reign, which lasted until 1155. Bhikşācara mounted further attempts to regain the throne during the first two years and no sooner had he been killed than another challenger, Lothana, a brother of Salhana, succeeded in taking control of Lohara. That territory was subsequently recaptured but challenges continued from Lothana and two others who sought the throne, Mallājuna and Bhoja, the latter being a son of Salhana. Throughout this period there was also further troublesome behaviour generally from the dāmaras, as so often in the past, and also as in the past it was the fact that those chiefs also fought among themselves which enabled Jayasimha to survive. Peace came after 1145 and Jayasimha was able to employ his methods of kingship, which relied on diplomacy and Machiavellian plotting, for the greater good of his kingdom. In particular, Kalhana refers to the piety of Jayasimha, who rebuilt or constructed many temples which had been destroyed during the long years of war. His success has led Hasan to describe him as "the last great Hindu ruler of Kashmir."[20][37][38]

An example of Jayasimha's vision can be found in his decision to enthrone his oldest son, Gulhana, as king of Lohara even though Gulhana was a child and Jayasimha was still alive. The reason for this appears to have been better to ensure the succession would not suffer any disturbance.[39]

Successors to Jayasimha

Jayasimha's rule continued until 1155, followed by his son Paramanuka, and then his grandson Vantideva (ruled 1165–72), who is often described as the last king of the Lohara dynasty.[13]

Dynasty of the Vuppadevas

With the end of the Loharas, Vantideva was replaced by a new ruler named Vuppadeva, who was apparently elected by the people, and who started the eponymous dynasty of the Vuppadevas.[13] Vuppadeva was succeeded in 1181 CE by his brother Jassaka, who then was succeeded by his son Jagadeva, in 1199 CE.[40] Jagadeva attempted to emulate Jayasimha but had a turbulent time, being at one stage forced out of his own kingdom by his officials. His death came by poison in 1212 or 1213 and his successors met with no more success; his son, Rājadeva, survived until 1235 but any power that he may have had was shackled by the nobility; his grandson, Samgrāmadeva, who ruled from 1235 to 1252, was forced out of the kingdom just as Jagadeva had been and then killed soon after his return.[41]

Another son of Rājadeva became king in 1252. This was Rāmadeva, who had no children and appointed Laksmandadeva, the son of a Brahmin, to be his heir. Although the period of Rāmadeva's reign was calm, that of Laksmandadeva saw deterioration in the situation once more. In this reign, which began in 1273, the troubles were caused not only by the fractious nobility but also by the territorial encroachment of Turks. As with his predecessors and successors, he thought little of spending money on border protection. By 1286, when Laksmandadeva'a son, Simhadeva, came to the throne, the kingdom was a much smaller place. Simhadeva survived until 1301, a largely ineffective ruler who was dominated by his advisers. He was killed by a man whom he had cuckolded.[41]

The last of the dynasty was Sūhadeva, the brother of Simhadeva. He was a strong ruler but also an unpopular one. He taxed heavily and exempted not even the Brahmins from his exactions. Although he managed to unite the kingdom under his control there is a sense in which the majority of it was united against him.

The widow of Sūhadeva, queen Kota Rani took his place but was usurped by Shah Mir, a Muslim who had moved into the area from the south. Kashmiris were "feeling extraordinarily pinched by the Arab aggression in the Indus valley", according to Ronald Davidson,[42] and some people had already converted to the religion from Hinduism. By the end of the 14th century the vast majority of Kashmir were still Hindus and the Brahmins still maintained their traditional roles as the learned administrators until the accession of Sultan Sikandar Butshikan of the Shah Mir dynasty.[43]

Impact

Mohibbul Hasan describes the collapse of order as:

The Dãmaras or feudal chiefs grew powerful, defied royal authority, and by their constant revolts plunged the country into confusion. Life and property were not safe, agriculture declined, and there were periods when trade came to a standstill. Socially and morally too the court and the country had sunk to the depths of degradations.[14]

See also

References

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

- Notes

- Ksitirāja, who was the son and heir of Vigraharāja, had abdicated his rights in favour of Utkarsa, ignoring the claim of his son due to disagreements with him.

- Kalaśa had at least one concubine.[22]

- Gargacandra and his sons, together with some others, were eventually strangled to death on Sussala's order in 1118,[34]

- Citations

- Chandra, Satish (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526) - Part One. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-81-241-1064-5.

- Hasan (1959), pp. 29-32.

- Stein 1900, p. 433.

- Thakur 1990, p. 287.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 2, pp. 293-294.

- Kaw, p. 91.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 2, p. 294.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, pp. 104-105.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 2, p. 370.

- "The Bodhisattva Sugatisamdarsana - Lokeshvara , about 1000 Bronze H . 13 5 / 8 in . ( 34 . 5 cm ) Musée des Arts Asiatiques - Guimet , Paris" in Pal, Pratapaditya (2007). The Arts of Kashmir. Asia Society. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-87848-107-1.

- "Réunion des Musées Nationaux-Grand Palais -". www.photo.rmn.fr.

- von Hinüber, Oskar, Professor Emeritus, University of Freiburg. "Bronzes of the Ancient Buddhist Kingdom of Gilgit". www.metmuseum.org.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - India - Early History, Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, 2016 p.63

- Hasan (1959), p. 32.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, pp. 106-108

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 108.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 110.

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, pp. 110-111.

- Hasan (1959), p. 33.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 111.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 113.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 112.

- Cribb, Joe (2011). "Coins of the Kashmir King Harshadeva (AD 1089–1101) in the light of the Gujranwalal hoard". Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society 208: 28–33, Fig. 1–9.

- Stein, (1900), Vol. 1, p. 114

- Stein (1900), Vol. 2, pp. 305-306.

- Stein, (1900), Vol. 1, p. 15

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, pp. 114-115.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 2, p. 295.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 117.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 16.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 119.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 120.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 122.

- "Vishnu and Shri Lakshmi on Garuda | LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, pp. 16-17.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, pp. 126-127.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 129.

- The History and Culture of the Indian People: The struggle for empire.-2d ed, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1966, p.101

- Hasan, p. 34.

- Davidson, p. 44.

- Stein (1900), Vol. 1, p. 130.

- Bibliography

- Davidson, Ronald M. (2004) [2002 (Columbia Univ. Press)]. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: a social history of the Tantric movement (Reprinted ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1991-7.

- Hasan, Mohibbul (2005) [1959]. Kashmir Under the Sultans (Reprinted ed.). Delhi: Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- Kaw, M. K. (2004). Kashmir and its people: studies in the evolution of Kashmiri society. APH Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7648-537-1. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Stein, Mark Aurel (1989) [1900]. Kalhana's Rajatarangini: a chronicle of the kings of Kasmir, Volume 1 (Reprinted ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0369-5. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- Stein, Mark Aurel (1989) [1900]. Kalhana's Rajatarangini: a chronicle of the kings of Kasmir, Volume 2 (Reprinted ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0370-1. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- Thakur, Laxman S. (1990). "The Khaśas: An Early Indian Tribe". In K. K. Kusuman (ed.). A Panorama of Indian Culture: Professor A. Sreedhara Menon Felicitation Volume. Mittal Publications. pp. 285–293. ISBN 978-81-7099-214-1.

._Mus%C3%A9e_Guimet_MA6266.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)