Lawrence Kavenagh

Lawrence Kavenagh (c. 1810 - 13 October 1846) was an Irish-Australian convict bushranger who, with Martin Cash and George Jones, escaped from Port Arthur, Van Diemen's Land, in late 1842. The three men took to bushranging for a six-month period, robbing homesteads and inns with seeming impunity. Kavenagh was tried for serious crimes on five separate occasions. He was executed in 1846 at Norfolk Island.

Lawrence Kavenagh | |

|---|---|

'Portrait of a man in the dock' by Charles Costantini (c. 1843), a portrait considered likely to be of Lawrence Kavenagh. | |

| Born | c. 1810 County Wicklow, Ireland |

| Died | 13 October 1846 |

| Occupation(s) | carter, stonemason, bushranger |

| Conviction(s) | Murder |

| Criminal penalty | Execution |

Biography

Early life and transportation

Lawrence Kavenagh was born circa 1810 in County Wicklow, Ireland. His birth-place was likely either Newbridge (now called Avoca) or nearby Rathdrum.[1]

In 1828, Kavenagh and his sister, Catherine, were convicted of burglary in Dublin. They were both sentenced to death, commuted to transportation for life. Lawrence Kavenagh was transported to New South Wales aboard the Fergusson with 40 other convicts, arriving in Sydney on 26 March 1829.[2]

When he arrived in the colony of New South Wales in 1829 Lawrence Kavenagh was assigned to work for Edward Reiley at Raby, in the Campbelltown area south-west of Sydney.

In February 1832 Kavenagh received forty lashes for insolence and disorderly conduct.[3] From September 1832 he was assigned to road gangs, but soon afterwards Kavenagh was reported to have absconded from the No. 20 Road Gang.[4]

On 8 February 1833 Kavenagh and Domick McCoy appeared before the Campbelltown Quarter Sessions, charged with assaulting Martin Grady with the intent to rob him. As reported, Kavenagh, McCoy and a third man had stopped Grady as he was driving his cart on the Liverpool Road and assaulted him “with sticks”. Grady drew “a pair of sharp shears” from his pocket to defend himself. The unnamed assailant ran away and Grady managed to wound Kavenagh and McCoy before they “escaped into the bush”. The pair were found guilty and sentenced to transportation for fourteen years.[5] Kavanagh was initially sent to the Phoenix prison hulk and then transported to Norfolk Island in March 1833.

Norfolk Island

At Norfolk Island in May 1833 Kavenagh spent fourteen days in irons for “refusing to assist in getting up the Boats”. In April 1834 he was sentenced to seven days in the cells for “rioting in Gaol”. In January (year not recorded) he received 150 lashes for “attempting to run away”.[3]

Lawrence Kavenagh spent nine years at the Norfolk Island penal settlement on this first occasion.[6] The last few years of Kavenagh’s incarceration on Norfolk Island was during the administration of Alexander Maconochie whose more benevolent methods of prisoner control were more focussed on prisoner rehabilitation rather than punishment. During Maconochie’s four-year term as Commandant of the penal settlement over fourteen hundred doubly-convicted men were discharged from Norfolk Island.[7]

The precise date that Lawrence Kavenagh departed from Norfolk Island is not known. Some sources claim he escaped from the island, but this is unsupported by any evidence.[8] A possible explanation for his appearance in Sydney in January 1842 is that he had been discharged under Maconochie’s regime, having served nine years of a fourteen year sentence. An alternative explanation is that Kavenagh was transferred as a prisoner from Norfolk Island to the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney.[9]

Return to Sydney

By January 1842, Kavenagh had returned to Sydney from Norfolk Island; whether he arrived as a free man or not, by mid-January he was incarcerated at the Hyde Park Barracks. By the 1840s the Hyde Park Barracks was being used for housing dangerous criminals.[10]

In 1842, the barracks were under the control of the notorious Deputy Superintendent, Timothy Lane, under whose watch the place “had descended into a dreaded place of brutality” where harsh punishment was the means of control and cruelty and corruption was entrenched among the convict officials.[11]

On 19 January 1842, Kavenagh received 36 lashes for “cutting his Irons”.[3] On January 27 Kavenagh and another convict, Thomas Brown, escaped from the watch-house at the Hyde Park Barracks.[12] On the evening of the escape the two men reached Double Bay and stole a fishing boat, in the process “threatening the life of a female” who sought to prevent them from doing so. The focus of the search for the escapees then shifted to the North Shore and the vicinity of Broken Bay. The next day it was reported that Kavanagh and Brown had robbed the house of Mrs. Reibey, Captain Innes’ mother-in-law, at Lane Cove where they stole various items including a musket.[13]

The colonial government offered a reward of ten pounds for the apprehension of either of the two convicts by “any free person”; for the apprehension of either absconder "by a prisoner of the crown" the reward offered was "the allowance of a conditional pardon. The published description of Lawrence Kavenagh was: height, 5 feet 7½ inches; complexion, "ruddy fresh"; brown hair, blue eyes and a "flat nose"; missing his "right little finger", "small scar on back of left hand, and on centre of forehead".[12] Kavanagh and Brown established a base on the North Shore of the harbour where they concealed the articles they had "obtained by plunder".[14] The bushrangers, during their brief period of “committing depredations in the neighbourhood of Sydney” moved freely from one side of the harbour to the other.[12]

On February 11 the Colonial Secretary, Edward Deas Thomson, Captain William Hunter, Edye Manning and Dr. Dobie were riding together along the beach at Rose Bay. Suddenly three men emerged from the bush at the edge of the bay, one of them (later identified as Kavenagh) holding a musket, prompting the riders put their horses into a canter to more quickly escape. One of the men cried out to Hunter: "If you don’t stop, by God we’ll shoot you". When Captain Hunter showed no sign of stopping Kavenagh fired two shots at him, both missing their target.[15][16]

After this incident parties of soldiers, mounted police and constables were sent off "in various directions to scour the bush". On the following day one group of four mounted police and an aborigine searching in the vicinity of Watson’s Bay discovered footprints and traced the bushrangers to a small cave where they managed to capture Kavenagh and Brown, as well as another man named Joseph Johnstone and “a woman dressed in man’s clothes” (a runaway assigned servant of Mr. Nalder named Elizabeth Kelly). The four captives were taken to Darlinghurst Gaol.[17][14] Kavenagh told Captain Innes that during his period of freedom "he had prowled about" the Hyde Park Barracks Watch-house, armed and disguised with glasses and wearing a white hat, hoping to "have a shot at" the Deputy Superintendent, Timothy Lane.[18]

On 12 April 1842 Lawrence Kavenagh, Thomas Brown and Joseph Johnson appeared before the New South Wales Supreme Court before Mr. Justice Burton, charged with illegally possessing firearms and having feloniously shot at William Hunter "with intent to murder him". The men pleaded not guilty. After the prosecution had presented its case, Lawrence Kavenagh spoke in his own defence. He claimed "he had never intended to do acts of personal violence when he took to the bush", but he was compelled to do so "by the tyranny he had experienced whilst in Hyde Park Barracks", adding that the tyranny he had endured at Norfolk Island "was nothing to that which he had experienced in Sydney". The jury returned guilty verdicts "without leaving the box".[15][16] The three convicted men were sentenced to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land for life.[19]

On 30 May 1842 Lawrence Kavenagh, along with forty-two other prisoners of the Crown (including George Jones),[20] was transported from Sydney to Van Diemen’s Land aboard the schooner Marian Watson, arriving at Hobart on June 8, from where he was taken to the Port Arthur penal settlement.[21][22]

Escape from Port Arthur

Towards the end of 1842, while in a work gang carting stone from the Port Arthur quarry, Kavenagh met two other convicts, George Jones and Martin Cash. The three convicts had a common interest: “a strong inclination to abscond”. Cash had made a previous attempt at escaping from Port Arthur, being captured within a mile of the mainland near East Bay Neck.[23] They discussed a plan of escape, and agreed to make the attempt on the afternoon of Boxing Day as the carts came up to the quarry for the first load.[24]

On Boxing Day, 26 December 1842, the escape occurred as planned. In Martin Cash’s words: “I walked deliberately over to where [Kavenagh and Jones] were at work; fixing my eyes on them for a moment, they both instantly dropped their picks, and springing on a steep bank, were lost in a minute in the scrub, I soon following their example”. Kavenagh took the lead, directing the others to where he had previously stashed a quarter of a loaf and some flour. Then the three convicts headed for the thick scrub at the foot of Mount Arthur. They decided to remain hidden in the bush for the next three days, expecting that the soldiers “would relax in their vigilance, under the impression that we had made our escape”.[25]

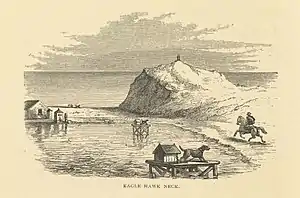

On the night of their third day of freedom they left their hiding place, keeping to the bush and flanking the coastline to their right. Near Long Bay they crossed a road and continued north-west through the bush to the side of Signal Hill, where they rested until morning. Cash made a "charcoal fire" in a hollow tree and cooked a damper for breakfast. The three convicts continued on through the thick scrub until dusk when they came in sight of Eaglehawk Neck where they could “see the line literally swarming with constables and prisoners”. Realising that crossing the Neck was impossible they decided to swim past it.[26]

Eaglehawk Neck is a narrow isthmus connecting the Tasman Peninsula (where Port Arthur was located) with the Forestier Peninsula. Across the neck were placed guards, lamps and chained guard-dogs, some of them on stages set out in the water. To the west of the Neck was the narrow Eaglehawk Bay and on the eastern side was the much wider expanse of Pirates Bay. Following Cash's lead the escapees chose the longer swim on the eastern side, about half a mile in width and the same route that Cash had taken on his first escape attempt.[27] Moving stealthily through the bush in darkness they reached the water-line along the arc of Pirates Bay and started swimming with their clothes bundled above their heads. With a strong wind blowing, waves crashed against the swimmers and carried away their bundles, so each of the men arrived naked on the other side.[28]

Finding themselves at the base of steep and scrubby hill the three convicts advanced up the slope and rested near the top until daybreak. Martin Cash knew of the location of a hut near the road connecting Eaglehawk Neck and East Bay Neck, normally occupied by a road-repair gang who had nearly completed their sentences. In their naked state and without shoes or food, the three convicts decided to take the risk of raiding the hut. They rushed through the door, Kavenagh holding an axe he had found outside, to find it occupied by only one man, the sub-overseer of the work gang. The man was tied to a post and clothes, boots and a quantity of food were procured.[29]

Realising that, upon discovery of their raid on the road-gang’s hut, the focus of those engaged in the pursuit would shift to the Forestier Peninsula and the East Bay Neck, the escapees decided to remain hidden for a few days more. At the northern end of the peninsula they considered swimming to the mainland (which was half the distance of their previous swim), but with a strong current flowing both Kavenagh and Jones expressed disquiet. Kavenagh told the other two “that he had a very narrow escape from drowning when crossing at the Neck, at one time giving himself up for lost, observing that it was nothing short of a miracle that he had reached the land”. Deciding to attempt a crossing by land at East Bay Neck, the three convicts waited for nightfall and, by stealth, managed to evade the sentries and then crawled through a field of wheat until they were a safe distance from the military barracks. A quarter mile further on they came to dense bush where they could momentarily relax, having “escaped the sharks by land and water”.[30][27]

Bushranging

Travelling north-west after their escape to the mainland from Port Arthur the three escaped convicts arrived at a bush hut and took bread, tea and sugar (as well as a billy) from the frightened residents. By the following morning they had reached a more populous district in the vicinity of Sorell. Keeping watch on a farmhouse during the day, they emerged at night and forced entry by knocking on the door and calling out “Police” upon enquiry. At that house they found a gun (of which Kavenagh took possession) and a complete change of clothes for each man. At a shepherd’s hut near Prosser Plains the convicts obtained a second gun. Moving further to the north-west, on 23 January 1843 they raided Blinkworth’s house in the Richmond district, where they carried off a double-barrelled gun and food.[31]

By 19 January 1843 a reward had been proclaimed for the apprehension of the three “runaways from Port Arthur”. The reward offered for the apprehension of “either of the said felons” was fifty sovereigns (pounds); if “this service be performed by a convict” a conditional pardon would be granted in addition to the pecuniary reward.[32]

Cash, Kavenagh and Jones next bailed up a public-house near Bagdad, during which one of the men under guard managed to escape while they were searching the premises, necessitating a "speedy retreat" and a resolution to better secure each person in the future. The following morning, now moving south-west towards Broadmarsh, they bailed up Elijah Panton and his family at their farmhouse, causing great distress to Panton’s pregnant wife, Jane. The intruders then secured a group of labourers from an outhouse as well as the household servants, before searching and plundering the contents of the house. After leaving Panton's farm the three bushrangers passed Dr. Macdowell on the road, who claimed he had hailed them and was answered by being fired upon. In the wake of these events Panton, who was a former convict, received a letter from the Colonial Secretary notifying him that "because the bushrangers were allowed to escape from his place, he is to be deprived of all his assigned servants".[33][34]

The Woolpack Inn shoot-out

On Tuesday evening, 31 January 1843, the three bushrangers arrived at the Woolpack Inn at Macquarie Plains, 12 miles north-west of New Norfolk on the Hamilton Road. They bailed up the publican’s wife, Mrs. Stoddart, her two adult sons and three customers. Cash enquired about a hut about fifty yards from the public-house, and Mrs. Stoddart replied that she “had no men there”. In fact, four police constables were stationed in the hut and they had noticed something was amiss at the hotel. Cash, upon glancing out the window, “perceived some people moving up to the house” and, alerting his comrades, he stepped out of the building and was “told to stand” by the approaching men. On being challenged Cash immediately fired his weapon, and Kavenagh and Jones, standing either side of him, also fired at the constables, two of whom were wounded in the exchange of fire. Each of the policemen then retreated to cover, Cash later claiming they “had behaved in a cowardly manner”. After the smoke cleared Cash found himself standing alone, Kavenagh and Jones having taken the opportunity to escape. Cash returned to the house and grabbed a three-gallon keg of brandy before he too departed, later joining his comrades at the spot where they had previously stashed their swags.[35][36][37][38]

Mount Dromadery base-camp

After the incident at the Woolpack Inn the three bushrangers travelled for three days towards a base they had previously established at Mount Dromedary (between Brighton and New Norfolk in the Black Hills area). On their way they stopped at Henry Cawthorne’s property at the foot of Mount Dromedary, tying up several men and raiding the house to obtain provisions, as well as a gun and ammunition. Following the raid on Cawthorne’s house it was reported that “the constables and military are in hot pursuit” of the outlaws.[36] By that stage, however, they had decided to lay low, spending the night at the home of old acquaintances of Martin Cash, an ex-convict named Thomas Blackburn and his wife Hannah who were living at Cobb’s Hill (towards the Jordan River).[39] The following day Hannah Blackburn travelled to Hobart Town and returned with Cash's de facto wife, Eliza (after having dodged police surveillance). The three bushrangers, accompanied by Eliza Cash, then repaired to their base-camp on nearby Mount Dromedary.[40]

In his memoir Cash refers to their elevated station as a "fortress", which he named 'Dromedary Park'. Situated near the top of Mount Dromedary it had commanding views of the Derwent River from the New Norfolk district to Brighton, an "airy tenement" where the bushrangers were "not likely to be surprised". The "fortress" consisted of three logs in a triangle shape, on the inside of which was placed branches of young trees and ferns. Though lacking a roof Cash described it as having “rather a comfortable appearance”. Kavenagh, Jones and Cash and his wife spent the next three days “in quiet retirement… enjoying the beauties of nature unadorned by art”. However, with their supplies running low, the bushrangers “resolved to take the field, and levy contributions”, leaving Eliza in charge of the fortress.[41]

Brighton and New Norfolk districts

On Tuesday, 7 February 1843, the three bushrangers entered the house of Hodgkinson, his wife and eighteen year-old daughter. Jones covered the captives with a double-barrelled gun while Kavenagh searched for food and other supplies and Cash stood outside on watch. Mrs. Hodgkinson proved to be a difficult proposition, verbally abusing the intruders and attempting to escape from the house on several occasions. As the bushrangers were leaving with their plunder, including six dried hams, she followed them outside “screaming at the top of her voice” and continued to lambast them until they were out of sight.[42][43] On Saturday, February 11, the three men suddenly entered the house at Collis’ farm in the bush near the road to Brighton, 17 miles north of Hobart Town. They were fed mutton and Cape wine by Mrs. Collis, before they locked her, with her young child, in the storeroom and departed with food, clothes and the remainder of the wine.[42]

On Wednesday, February 22, Cash, Kavenagh and Jones stopped four men in a cart near Thomas Shone’s 300-acre property in the Back River district (north-east of New Norfolk). They bound the men and proceeded to the house, where Shone, his wife and a guest were bailed up, each of the outlaws armed with a double-barrel fowling-piece and a brace of pistols. Soon afterwards a spring cart arrived with other members of the household and their guests. Seven men from a nearby hut were also tied up and brought to the house, making a total of nineteen being held captive in one room. After stopping for nearly an hour the bushrangers departed with food and assorted stolen valuables. Thomas Shone was later informed that, for allowing the bushrangers to escape, he too would be deprived of his assigned servants.[38][44] This decision by the Colonial Secretary became the subject of criticism and ridicule in the colonial press.[45]

On returning with their stolen goods to their Mount Dromedary base-camp, the bushrangers learned that the King’s Own Light Infantry, under command of Major Ainsworth, had been given the task of pursuing them. Several days later, from their elevated position, they watched “several parties of police and military scouring the country” searching for them, “taking all directions but the right one”. Cash urged Eliza to return to Hobart Town, being concerned for her safety. After she had left the three men decided a change in their sphere of activity would be necessary, prompting the bushrangers to relocate further inland and to the north, to the districts around Hamilton.[46]

On 1 March 1843 the colonial Government, in a response to the widespread belief that the bushrangers were being assisted and supported by other convicts, amended the reward offered to a convict for the apprehension of the three “runaways from Port Arthur”. It was announced that any convict “who shall apprehend or give such information as shall lead to the apprehension” of either Cash, Kavenagh or Jones would receive, instead of the previously advertised conditional pardon, a free pardon as well as a free passage from the colony (in addition to the pecuniary reward of fifty sovereigns).[47]

Hamilton and Bothwell districts

On Saturday, March 11, Cash, Kavenagh and Jones visited the residence of Thomas Triffett at Green Hills on the River Ouse (about 9 miles north-west of Hamilton), robbing it “of everything they could carry away”. They took Triffett’s gun and left behind one they had earlier stolen from Henry Cawthorne, deeming it inferior to the one lately obtained, and asking Triffett to return the gun to Cawthorne (“telling him at the same time, that as soon as they met with a better one than his, they would return it also”).[48]

On Sunday, March 19, the bushrangers arrived at Charles Kerr’s station, ‘Dunrobin’, about 14 miles west of Hamilton. They had been observing the place for two days beforehand, and had taken a shepherd prisoner in order to interrogate him about the place they intended to plunder. They left with a pair of duelling pistols, clothes and a telescope to aid their careful observations of human movement.[49][50] On the following Wednesday the bushrangers paid a visit to John Sherwin of ‘Sherwood’ station, between Hamilton and Bothwell, an incursion which followed a familiar pattern.[49]

Heading south-east the three bushrangers struck next on March 25 at Thomas Edols’ house at 'The Bluff' at Macquarie Plains (near the Woolpack Inn). On approaching the homestead they were attacked by a large dog which Cash shot. Breaking through the door they found Edols and his family members inside. There were obvious signs of preparation in case of an incursion; the bushrangers found three loaded guns behind a door and a pair of duelling pistols which Edols was attempting to conceal as he sat on the sofa.[51][52] Edols later provided interesting comparative descriptions of the three men who had robbed him: “Cash is represented as a low-speaking, foul-mouthed man; Kavenagh the most quiet of the three; and Jones the most intelligent”.[53] From as early as February 1843 the colonial newspapers had begun to use the shorthand term ‘Cash & Co.’ to describe the three bushrangers, Cash, Kavenagh and Jones.[54] The term became increasingly common as their exploits increased and they remained at large. Martin Cash was better known in Van Diemen’s Land, having lived on the island since 1837 and gaining considerable notoriety for making two separate escape attempts from Port Arthur. There is, however, some doubt regarding who was the real leader of the gang, with mistaken identity probably playing a part.[55] After Kavenagh was wounded and subsequently captured in July 1843 the Colonial Times newspaper commented” “We have no doubt Cash and Jones will soon be captured – their strength is broken”.[56]

The bushrangers made their next appearance east of Hamilton in the Green Ponds district. On March 29 they arrived at Captain Clark’s ‘Hunting Ground’ farm near Green Ponds township. Finding the house occupied by “three ladies and a woman servant only” they left after only a short time taking only a newspaper and some apples, “fearful that someone… had escaped their hands and gone for assistance”. Later that day the outlaws robbed John Thomson’s house in the same district, turning up a half hour after a party of soldiers and constables had left when they had received a report of the raid upon Captain Clark’s farm.[51]

On Saturday morning, April 15, Cash, Kavenagh and Jones robbed George Stokell’s farmhouse at The Tiers near Mount Jerusalem, north-west of Bothwell. Representing themselves as constables in search of the bushrangers, the overseer Bell “observed he did not think the bushrangers were thereabouts”, to which Cash replied: “They are nearer to you than you think”. After a breakfast of ham and eggs, the outlaws left, taking provisions and a few items of clothing, including the overseer’s boots.[57]

On Wednesday, April 26, the bushrangers met a magistrate, John Clarke, riding on the road near Bothwell and compelled him to accompany them to the Allardyce’s homestead on the River Clyde where they stole clothing and provisions, and two guns and ammunition. The bushrangers were described by Clarke “as having a miserably haggard appearance, badly clothed, and with scarcely a shoe on their feet”.[58] It was generally believed by this time that the career of ‘Cash and Co.’ was drawing to a close. A newspaper report a fortnight earlier had ventured the opinion that, “hemmed in on all sides, miserably jaded, restless, and apprehensive, they will fall easy victims to the first party they encounter”.[57] On Tuesday, 9 May, they raided Espie’s station at Bashan Plains, 18 miles north-west of Bothwell, taking away provisions as well as a couple of horses to carry their plunder.[59]

On Friday, May 19, the bushrangers held up Captain McKay on the River Dee (west of Bothwell). After dining with him, in company with his neighbour Thomas Gellibrand, they loaded two horses with provisions and travelled with their captives the three miles to Gellibrand’s run, where they loaded a third horse and departed. A report of these events surmised that the outlaws had stocked up with supplies and were headed for their “winter quarters, from whence, we should think, they will not be heard of for some time”.[60] The report was correct; Cash, Kavenagh and Jones now returned to their base-camp on Mount Dromadery.[61] In late May James Morrison and a party of constables tracked the bushrangers’ route of departure from Captain McKay’s farm and found their stash of stolen supplies. The horses, saddles and bridles were found twelve miles away, in a deep ravine.[62] A newspaper report of the discovery of the bushrangers’ supplies concluded with the following sanguine comments: “so that instead of going quietly as they purposed into winter quarters, they will be compelled to enter into active operations, a course which will render their capture certain, so vigilant are their present pursuers”.[63]

The Antill Ponds shoot-out

Cash, Kavenagh and Jones spent the remainder of May and the first few weeks of June 1843 at Mount Dromadery or with the Blackburns at nearby Cobb Hill.[65] On the evening of Wednesday, June 21, they bailed up the Half-way House, an inn kept by Edward Greenbank on the road between Oatlands and Ross at a rural locality called Antill Ponds in the Salt Pan Plains district. After the outlaws departed Greenbank instructed his ticket-of-leave servant to ride to Oatlands to report the robbery. The bushrangers went directly from the Half-way House to William Kimberley’s homestead, two miles to the east.[66] After shooting the lock and entering, they saw a constable, who had been sent to guard the house, in the process of exiting through a window. Fearful of a possible ambush the outlaws left soon afterwards and cautiously made their way through the night to a nearby hut belonging to Samuel Smith, one of Cash’s old acquaintances. Leaving their knapsacks by the door they entered the hut and greeted the occupants. Just as they began to share a bottle of liquor with Smith and his two companions, they heard a voice from outside: “Surround the hut; we have them, here’s their swag”. A party of seven soldiers and three constables sent from Oatlands had caught up with them at the hut. In Cash’s description, in reply he grabbed his gun, opened the door and “discharged both barrels to the right and left”. Kavenagh and Jones gathered their arms, extinguished the light and the three left the hut, firing as they went. In the darkness the only light was the flash of gunfire as the parties returned fire. In Cash’s words: “This was merely random firing, the darkness of the night preventing us from seeing each other, neither had either side the wish to get into close quarters”.[67] More than a hundred shots were fired in the exchange between the parties, resulting in one of the soldiers receiving a slight wound.[68][69] After the firing had finished the three outlaws laid low in the darkness, hiding themselves behind logs and trees while the soldiers and constables “were beating the bush for them”. The equipment they lost as a result of the skirmish at Antill Ponds included their telescope and bullet mould.[70]

After the bushrangers had made their escaped, the soldiers and constables, and a group of five volunteers who had also joined the fight, called at Robert Harrison’s place, less than a mile from the scene of the conflict. Harrison was a local magistrate and, when informed of the result, (by Cash’s account) “he called them a cowardly set of rascals, ordering them immediately to leave the premises, remarking that they should be ashamed to confess that fifteen, all well armed, were not able to capture three careworn bushrangers!”.[67]

Campbell Town district

Late-morning on Saturday, June 24, Lawrence Kavenagh walked up to Christopher Gatenby, a landholder on the River Isis (between Campbell Town and Norfolk Plains), and asked for “the master”. Gatenby informed the stranger that he was the master, at which point Kavenagh unbuttoned his greatcoat, pointed to a pair of pistols in his belt and “stated the object of his visit”. The three bushrangers, reported as being “in a half-famished state”, accompanied Gatenby to his house where they ate dinner and drank several bottles of wine, “acting with politeness throughout, and treating the ladies with great respect”. Afterwards they collected clothes and provisions and departed, ordering Gatenby and two of his men to accompany them and carry their plunder into the foothills of the Great Western Tiers.[71][70]

After camping for three days on the Lake River, the bushrangers headed east towards the Macquarie River, hearing from informants of a police presence in farm houses along the way. On Friday morning, June 30, Cash, Kavenagh and Jones were approaching Cains’ residence on the Lake River, when they saw or heard something to indicate a trap; they immediately wheeled around and headed for the scrub. The party of constables who were stationed in the house ran out after them. The bushrangers fired several rounds at their pursuers, who returned fire. The outlaws managed to outrun the police but were forced to abandon the supplies they had taken from Gatenby.[72] Eventually, “finding ourselves very much fatigued, and also short of provisions”, the bushrangers arrived at James Youl’s property on the Macquarie River where they visited a shepherd, another acquaintance of Cash’s. As they were nearing their destination, they had been spotted by men working on a neighbouring property, who decided to arm themselves and follow the bushrangers with the intention of capturing them. Later that evening at the shepherd’s hut, voices were heard outside and Cash opened the door and fired at a man holding a firearm, hitting the gun and separating the stock from the barrel. With their prospective captors in retreat, the gang gathered some provisions and crossed the Macquarie River to camp for the night.[73][74]

Late morning on Monday, July 3, the three bushrangers stopped the Launceston coach on the main road near Epping Forest, north-west of Campbell Town, and robbed the passengers. The outlaws were described as having “a squalid and miserable appearance” and “exhibited great haste and trepidation” during the robbery. The coach was detained for only about ten minutes during which Mrs. Cox, the coach proprietor, “rebuked them in severe terms for the wickedness and folly of their career”.[72][75]

On 5 July 1843 the colonial Government proclaimed that the reward for “the capture of either of the armed runaway Convicts, Martin Cash, George Jones and Lawrence Kavenagh” was increased to one hundred acres of land or one hundred sovereigns (in addition to the fifty sovereigns, free pardon and passage from the colony previously offered). If the person entitled to the reward was a convict, the monetary reward would be the sole option.[76]

After the coach robbery the bushrangers walked through the bush, avoiding inhabited areas, until they were near the township of Ross, seven miles south of Campbell Town. On Friday evening, July 7, they arrived at Captain Horton’s house and being refused admittance, broke open the door. Horton’s cook, an assigned convict servant named William Jackson, was shot in the shoulder during the incursion. George Jones was later charged with shooting Jackson, which he claimed was due to an accidental discharge of his gun.[77] The bushrangers' overall conduct was described as “extremely violent, having several times rushed at Captain Horton in a ferocious way, menacing to shoot him if he did not find them money”. During these events Horton’s wife managed to escape so the outlaws were forced to depart in haste.[78][79]

Accident and surrender

After leaving Horton’s place the three outlaws sought a hiding-place in the Western Tiers, but with parties in close pursuit, they headed for the wilderness area of the Lakes. Along the way they bailed up a shepherd’s hut at a place called Dog’s Head and obtained some rations for the trip.[78] While crossing a mass of limestone rock near Lake Sorell, Lawrence Kavenagh stumbled and fell, causing his firearm to hit a rock and discharge. The ball entered his arm at the elbow, followed the bone and exited from his wrist. The wound was bandaged with a torn up white shirt. Kavenagh was faint but could walk and the bushrangers decided to return in the direction of Bothwell, with Cash planning to enter the township after dark and abduct the doctor in order to treat his injured comrade. That evening when they camped Kavenagh told them he was resolved to give himself up to the magistrate, John Clarke of ‘Cluny’, near Bothwell (whom the bushrangers had bailed up in April, compelling him to accompany them to Allardyce’s homestead). Cash and Jones “used every argument and entreaty in trying to alter his determination”, but to no avail. The next morning they accompanied Kavenagh to within a short distance of Clarke’s place before they parted. In his memoir Cash disclosed that Jones had “privately hinted the necessity of shooting Kavenagh” in case he would reveal their haunts and their visits to the Blackburns at Cobb’s Hill, for which suggestion Cash rebuked Jones, telling him he regretted “very much to hear him suggest anything so unmanly”. Cash and Jones returned “in very bad spirits”, and Cash admitted he “now became disgusted with my calling, being of opinion, after what had lately transpired, that there could be no confidence or friendship between men placed in our position”.[80]

Kavenagh arrived at one of the huts on John Clarke’s property on Tuesday evening, July 11; he was wrapped in a blanket and was described as being “in a wan and wretched condition”.[78] One of the men from the hut went up to Clarke’s house with the message that Kavenagh “had come to give himself up”. Clarke was absent, but his overseer sent servants to take charge of the wounded man and sent for the doctor. Kavenagh was taken to Bothwell the following day. On Saturday, July 15, Kavenagh was brought to Hobart Town, attended by an escort of soldiers and constables. He was described as having a very emaciated appearance and “evidently suffering acute pain from his wound”. It was reported that “the excitement and anxiety of the inhabitants to have a look at him was intense”, with a large crowd gathered at the gates of the gaol.[81]

Trial and sentencing

Kavenagh’s former comrade-in-arms, Martin Cash, had been captured in Hobart on August 29 after a shoot-out which resulted in the death of a constable.[82] Cash’s trial was held on September 6 (the day before Kavenagh stood trial).[83]

Lawrence Kavenagh, with his arm in a sling, was tried on Thursday, 7 September 1843 before Justice Montagu and a jury. The charge related to a single incident, namely the robbing of the Launceston coach near Epping Forest on July 3. Kavenagh was charged with “having feloniously and violently put in bodily fear James Hewitt [the coach-driver] and from his person taken one watch and seven promissory notes of the value of £1 each”. Kavenagh pleaded not guilty and requested that he be allowed to have counsel represent him; the judge refused the request, saying “I can see no necessity that the prisoner should have that indulgence”.[84]

Testimonies were given by the coachman, James Hewitt, a passenger named John Dart and the coach proprietor (who was also a passenger), Mary Ann Cox. The evidence was largely concerned with establishing that Kavenagh was one of the three men who held up and robbed the coach, as well as examining each person’s recollection of the events. Mrs. Cox testified: “I did not see the prisoner take anything from Hewitt; I firmly believe Kavenagh was one of those who said, ‘you need not be frightened’”.[84] This accords with the account in Cash’s memoir that Kavenagh’s role during the robbery was to stand at the horses’ heads.[85]

When he was asked if he had anything to say to the jury, Kavenagh asserted he had “fled” from Port Arthur “at the hazard of my life”, being a place “where men are treated worse than dogs, and where it is almost impossible to live”. He maintained he had never committed “any barbarous act, nor violence to the female sex”. Kavenagh claimed that he would have pleaded guilty, except that he had been indicted for violence, which he rejected, adding: “if I met any armed man, I did the best I could, I stood my ground; but to use violence against unarmed persons was never in me; I never was guilty of so cowardly an act”.[86] In summing up, Justice Montagu instructed the jury that their decision in the matter “was wholly irrespective of the manner in which the prisoner had acted whilst in the bush, or of the hardship or ill-treatment he might have suffered at Port Arthur”. The jury “retired for a few minutes and brought in a verdict of Guilty”.[84]

Death sentence and reprieve

At noon on Friday, 15 September 1843, the court convened in order for Justice Montagu to pass sentence on a number of prisoners, including Lawrence Kavenagh and Martin Cash. The court "closely thronged with spectators". During his discourse preceding the sentencing of Cash and Kavenagh, Justice Montagu described Kavenagh as "a plausible, subtle, and an artful man, who could string his words very plausibly together; but he was at the same time one of the most abandoned and worst of characters". After a lengthy address on the subject of the crimes committed by the two men, during which Cash interjected on a number of occasions, the judge passed sentences of death upon both Cash and Kavenagh.[87]

On the day following their sentencing a petition was presented to the Lieutenant-Governor Sir John Eardley-Wilmot by Rev. Therry praying that the lives of Cash and Kavenagh might be spared. Eardley-Wilmot granted a reprieve soon afterwards to Lawrence Kavenagh, who was then moved from the Gaol to the Penitentiary.[88] The report of Kavenagh's reprieve in The Courier newspaper was scathing; “The life of this miserable and criminal creature has been spared at the moment when death was apparently his only hope”.[89] Shortly afterwards Cash also received a reprieve.[90] Both Cash and Kavenagh had their sentences commuted to transportation for life.[91]

From early 1844 the process commenced of transferring the administration of the Norfolk Island penal settlement from New South Wales to the government of Van Diemen’s Land. A new commandant, Joseph Childs, had arrived at the island in February 1844.[92] In late April 1844 one hundred "desperate offenders", including Lawrence Kavenagh, were put on board the government barque, Lady Franklin, for conveyance to Norfolk Island, which departed for the island on April 30.[93][94] On the news of the departure of the Lady Franklin, the Colonial Times newspaper observed: “The colony has been relieved of a considerable number of the most incorrigible of the prisoners… where we learn the 'worst than death system' has re-commenced in all its glory”.[95]

Return to Norfolk Island

The convicts held on Norfolk Island at this time were made up of doubly-convicted colonial prisoners and those who had been sentenced to transportation for 15 years or life in the United Kingdom. Amongst the colonial prisoners (known as 'old hands') were many inveterate law-breakers who had engaged in activities such as bushranging, cattle-thieving, robberies, burglary and piracy.[96] These were the ‘flash-men’ of the settlement who displayed extreme contempt for authority and scorned the punishments that were meted out. The elite amongst this set of hardened criminals was a group known as ‘the Ring’ who dominated the other prisoners and were contemptuous of the guards and overseers who supervised them day-to-day.[97]

In December 1844 it was reported that Kavenagh “was behaving well” on Norfolk Island. He had been appointed overseer “to a number of sick persons” on the island, “and hitherto his conduct had been most exemplary”.[98]

In February 1845, after his sentence of death was revoked, Martin Cash was transported to Norfolk Island aboard the brig Governor Phillip.[98][99] On arrival at the island Cash and the other prisoners from the ship were marched to the barrack yard where the issuing of clothing, numbering and recording of descriptions were carried out. After these preliminaries were completed they were taken to the lumber-yard, surrounded by a high wall with a wooden cookhouse and mess-room to one side, where Cash was reunited with his “old companion in arms Kavanagh”.[100] Before very long, however, Kavenagh and Cash had a falling out. Cash claimed that Kavenagh “appeared to assume a tone of superiority over me, as on one occasion he observed while in conversation that I was very well while in the bush under arms, but that at Norfolk Island I knew nothing”.[101]

The colonial prisoners normally prepared and ate their meals in the lumber-yard, adjacent to the cookhouse. On 30 June 1846 William Foster, Superintendent of Colonial Prisoners, ordered the collection and removal of cooking vessels from the lumber-yard, to be carried out in the evening after the prisoners were locked in their barracks. The subsequent search of the lumber-yard yielded a large number of cooking articles, which were placed in the Convict Barracks store.[102]

Rebellion

On the morning of 1 July 1846 the 'turn-out' bell rang and the convicts were assembled in the prison barrack-yard for prayers. After the prayers were read, the men were marched to the lumber-yard where they were to take their breakfast. They were accompanied by Patrick Hiney, Assistant Superintendent of Convicts, who took the muster. A group of men of 'the Ring' surrounded Hiney and complained that the kettles and cooking pans had been taken away. Hiney left the group and went to the nearby cookhouse and told the overseer, Stephen Smith, he thought trouble was brewing.[103]

When Hiney left the cookhouse he found that a great number of the prisoners were in an agitated state. Hiney walked over to William Westwood, a former bushranger from Van Diemen’s Land known as 'Jackey-Jackey'. As he began talking to Westwood, the surrounding body of prisoners, including Westwood, made a rush out of the lumber-yard to the Convict Barracks store where they retrieved the cooking utensils that had been confiscated the previous evening.[103][96] By Cash’s account, Kavenagh was one of those who “broke open the door of the store and took possession of the tin kettles”.[104] What then followed was a short period of relative calm as the men returned to the lumber-yard and began cooking their breakfasts over wood fires. Hiney left to tell the overseers and constables to prepare to march the convicts to their work stations.[103]

The period of calm was suddenly broken when somebody cried out: "Come on, we will kill the -----", and a group of men led by Westwood, grabbing pieces of wood and axes, ran for the gates of the lumber-yard. Convict Constable John Morris was stationed by his hut at the gate and was killed by Westwood with an axe blow to his head. Two other constables were knocked to the ground by the mob.[105] The mob then rushed to the cookhouse and brutally murdered the overseer, Stephen Smith, beaten about his head with wooden billets and repeatedly stabbed with a large carving fork.[96] William Westwood was then reported to have shouted: "Come on you -----; follow me and you follow to the gallows". About sixty of the men rushed out of the lumber-yard following Westwood, while the rest of the prisoners remained in the yard, “fearful of the outcome of this explosion of hate and killing”.[105] Westwood and his mob reached the first of a row of huts near the Lime-kilns (about a hundred yards from the lumber-yard) where two convict constables were asleep after coming off night-duty. Westwood entered the hut and killed John Dinon with two savage axe-blows to the sleeping man's head. Thomas Saxton woke to the noise but before he could rise, he also received a fatal blow from the axe.[96] Then a cry went up: "Now for the Christ-killer", the prisoners’ name for the hated Stipendiary Magistrate, Samuel Barrow, who was notorious for his harsh punishments and "arbitrary assertions of authority".[106]

By this time, however, the military had been alerted to the rebellion and Captain Conran and about twenty men of the 11th Regiment were advancing towards the lumber-yard. The mob at the lime-kiln hut, seeing the armed soldiers coming, ran back to the lumber-yard hoping to merge back into the larger body of prisoners (numbering about 500). The soldiers arrived at the lumber-yard and restored order by force of arms. The prisoners were then ordered by Captain Conran to pass out of the yard one at a time, each being searched for weapons and inspected for blood on their hands or clothing. While the search was in progress additional soldiers arrived under the command of Major Harold. When it was William Westwood’s turn to come out of the lumber-yard he walked over to the Major, his hands, face and shirt covered in blood, and said: "I suppose it’s me you want". Those suspected of being implicated in the murders (about sixty in all) were placed in a bunch and kept under guard and the rest of the prisoners were removed to the barrack-yard.[96][107]

On the afternoon of the uprising a Commission to investigate the insurrection was held by Major Harold, Captain Hamilton of the Royal Engineers and Samuel Barrow, the Stipendiary Magistrate. They took evidence from those who had witnessed the events and others who had been on duty at the time.[108] During the ensuing weeks Magistrate Barrow conducted preliminary trials which reduced the number of accused principal participants of the mutiny to twenty-seven (including Kavenagh). These prisoners were transferred to the Old Gaol to await their trial.[109]

Within ten days of the insurrection the brig Governor Phillip arrived at Norfolk Island from Van Diemen’s Land with a cargo of stores for the settlement. The ship had departed before news of the mutinous outbreak reached the colony. Amongst the official despatches was one informing Major Childs that his replacement, John Price, formerly Police Magistrate at Hobart Town, was to shortly arrive at the island. The Lady Franklin sailed from Hobart Town with John Price and his family on board, departing before the Governor Phillip arrived back with the news from Norfolk Island.[109] Also on board the Lady Franklin was Francis Burgess, a judge appointed to conduct the trials of nine convicts gaoled several months previously on stabbing, robbery and "unnatural offence" charges.[110][111] When they arrived at Norfolk Island the new Commandant and Judge Burgess were informed that rather than just nine, there were dozens of men that needed to be tried.[109] The trials of the nine oldest cases began on July 22, conducted by Judge Burgess, and were concluded on the following day. However, the business of the Court was unable to proceed any further when the judge became seriously ill with dysentery, to the extent that his "life at one period was despaired of".[111][112] Burgess returned to Hobart Town on the Lady Franklin and the trials of the mutineers were delayed until the arrival on the island of another judge.[109]

Trials and executions

The new judge, Fielding Browne, departed from Hobart Town for Norfolk Island on September 3. By this stage the accused prisoners numbered fourteen, considered to have been the ringleaders of the mutiny, one of whom was Lawrence Kavenagh. Martin Cash, who had witnessed the events, later wrote that even though "his old friend" was one of those who earlier broke into the store to retrieve the cooking pots, Kavenagh took no part in the subsequent murderous events as he was “down at a creek at the rear of the lumber yard at the time of the occurrence”. Cash claimed that Kavenagh was falsely accused by a prisoner known as ‘Dog Kelly’ who had a grudge against him for a perceived insult. Kelly “took advantage of the opportunity now offered to resent the insult, which rancoured in his mind, by swearing that Kavanagh was one of Westwood’s party”. Cash added the comment, “At this time an innocent man was just as likely to suffer as a guilty one”.[113]

The trial of the fourteen men – William Westwood, John Davies, Samuel Kenyon, Dennis Pendergrast, Owen Commuskey, Henry Whiting, William Pearson, James Cairns, William Pickthorne, Lawrence Kavenagh, John Morton, William Lloyd, William Scrimshaw, and Edward McGinnis – commenced on 23 September 1846. The trial was held in the schoolroom at the prisoners' barracks in front of a jury of seven army commissioned officers.[114] The men were charged with murder and aiding and abetting murder and all pleaded not guilty. Witnesses gave evidence for the Crown over several days concerning John Morris’ murder and in the end twelve of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to hang. Two of the fourteen, John Morton and William Lloyd, were acquitted.[115][116]

The convicted men were attended by ministers of religion during their confinement. The three Protestants (Westwood, Whiting and Pickthorne) were attended by the Anglican minister, Rev. Thomas Rodgers and the Roman Catholic prisoners by Fathers Murray and Bond.[114] Before he was executed William Westwood declared "as a dying man" to Rev. Rodgers that four of the twelve condemned men – Kavenagh, Whiting, Pickthorne and Scrimshaw – were innocent of the charges. Westwood was reported to have claimed: "I never spoke to Kavenagh on the morning of the riots; and these other three men had no part in the killing of John Morris, as far as I know of".[116]

The executions were carried out on the morning of Tuesday 13 October 1846, in two batches of six. The gallows were erected in front of the new gaol, the structure of the scaffold consisting of two beams, from which the ropes were hanging, with trapdoors that fell from each side of the centre. The first six men executed at eight o’clock were Westwood, Davis, Pickthorne, Kavenagh, Commuskey and McGinnis. An armed force of 30 soldiers were in attendance and the executions were supervised by Captain Blatchford, Superintendent of Convicts. At ten o’clock the remaining six prisoners were hanged. After each set of executions the bodies were placed in rough wooden coffins, loaded onto two bullock carts and taken to a disused saw-pit outside the cemetery where they were buried.[115][117][114] The location of the burials, in unconsecrated ground outside the cemetery fence, is known on the island as 'Murderers' Mound'.[118][119]

See also

References

Notes

- Two sources from 1842 show either option as Kavenagh's "native place": (1) Register (Van Diemen's Land), Description lists of convicts convicted locally or arriving on non-convict ships (1842), page 111; Lawrence Kavanagh; age 33; "New Bridge, County Wicklow" (Ancestry.com); (2) Indents of Convicts Locally convicted or Transported from Other Colonies (Van Diemen's Land), Marian Watson indent 1842; Lawrence Kavenagh (Police No. 860); age 30; native place: "Redrum, Wicklow".

- "Lawrence Kavanagh". Convict Records. State Library of Queensland. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Conduct Registers of Male Convicts arriving in the period of the Assignment System (Convict Department, Van Diemen’s Land), Kavenagh Lawrence, "Extract from Sydney Records".

- Principal Superintendent of Convict’s Office, Sydney, 10th September, 1832, New South Wales Government Gazette, 12 September 1832 (Issue No. 28), page 290.

- Campbelltown Quarter Sessions, The Currency Lad (Sydney), 16 February 1833, page 3.

- In 1843 Mr. Justice Montagu of the Van Diemen's Land Supreme Court, in summarising Lawrence Kavenagh’s criminal record, stated: “He had been for nine years at Norfolk Island, where the very worst of characters were congregated”; in Supreme Court. – Criminal Side, Colonial Times (Hobart), 19 September 1843, page 3.

- Hazzard, Margaret (1984). Punishment Short of Death: a history of the penal settlement at Norfolk Island. Melbourne: Hyland. p. 179. ISBN 0-908090-64-1.

- There were a number of escape attempts from Norfolk Island in the period 1833 to 1842, but only one was successful (to the extent of leaving the island). On 1 December 1840 six prisoners escaped in a whale boat; details of the escapees (including their names) were continuously published in the New South Wales Government Gazette [see example: The undermentioned Prisoners…, 22 January 1841 (issue No. 6), page 123]. The fate of these escaped prisoners was much speculated upon, but they probably perished at sea (see example: Norfolk Island, 12 February 1841, page 4).

- An entry in a Convict Indent for Lawrence Kavenagh after he was transported to Van Diemen’s Land reads: “ret’d from Norfolk Island” (which could be construed either as a free man or a prisoner); Indents of Convicts Locally convicted or Transported from Other Colonies, page 209 (third entry); see also Lawrence Kavenagh (the left-hand side of the same entry).

- "Fear 1826-48". Hyde Park Barracks. Sydney Living Museums; NSW Government. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- Dr. Fiona Starr (12 July 2017). "A day in the life of a convict: 1844". Hyde Park Barracks. Sydney Living Museums; NSW Government. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- Twenty Pounds Reward, or a Conditional Pardon, Australasian Chronicle (Sydney), 10 February 1842, page 4.

- The Hyde Park Runaways, Sydney Herald, 1 February 1842, pg. 3.

- The Bushrangers, Sydney Free Press, 15 February 1842, page 3.

- Supreme Court. – Criminal Side, The Australian (Sydney), 14 April 1842, page 2.

- Supreme Court, Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 14 April 1842, page 2.

- Capture of the Bushrangers, The Australian (Sydney), 15 February 1842, page 2.

- Domestic Intelligence, Sydney Free Press, 17 February 1842, page 3.

- Law Intelligence, Teetotaller and General Newspaper (Sydney), 16 April 1842, page 3.

- Indents of Convicts Locally convicted or Transported from Other Colonies (Van Diemen's Land), Marian Watson indent 1842; George Jones (Police No. 1250).

- Shipping Intelligence, Colonial Observer (Sydney), 1 June 1842, page 276.

- Ship News, Colonial Times (Hobart), 14 June 1842, page 2.

- Cash, pages 62-63.

- Cash, page 65.

- Cash, page 66.

- Cash, pages 66-67.

- Port Arthur, Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil (Melbourne), 9 August 1873, page 86.

- Cash, pages 66-67.

- Cash, pages 68-69.

- Cash, pages 69-71.

- Cash, pages 71-73.

- Reward!, The Courier (Hobart), 27 January 1843, page 4.

- Cash, pages 73-74.

- Cruel Treatment, Colonial Times, 7 February 1843, page 3.

- Cash, pages 75-77.

- Bushranging, Launceston Courier, 6 February 1843, page 2; reprinted from the H. T. Courier.

- The Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 7 February 1843, page 3.

- Bushranging, The Courier (Hobart), 24 February 1843, page 2.

- Hiener & Hiener, page 77.

- Cash, pages 77-78.

- Cash, page 78.

- Bushranging, The Courier (Hobart), 17 February 1843, page 2.

- Cash, pages 80-81; Cash’s memoir places this incident later in February, but the newspaper reports are explicit about the date.

- Mr. Shone’s Petition, Colonial Times (Hobart), 16 May 1843, page 2.

- For example, see: Editorial, Colonial Times (Hobart), 4 April 1843, page 2.

- Cash, pages 79-80.

- Reward!, The Courier (Hobart), 3 March 1843, page 4.

- The Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 14 March 1843, page 3.

- The Bushrangers, Launceston Examiner, 1 April 1843, page 7.

- Hobart Town Police Report, Colonial Times (Hobart), 4 April 1843, page 4.

- The Bushrangers, The Courier (Hobart), 31 March 1843, page 3.

- Cash, pages 85-86.

- Hobart Town Police Report, Colonial Times (Hobart), 4 April 1843, page 4.

- The Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 14 February 1843, page 3.

- Hiener & Hiener, page 75.

- the Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 18 July 1843, page 3.

- The Bushrangers, The Courier (Hobart), 21 April 1843, page 2.

- The Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 2 May 1843, page 3.

- The Bushrangers Cash and Co., Colonial Times (Hobart), 16 May 1843, page 3.

- The Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 23 May 1843, page 3.

- Cash, pages 93-94.

- Letter to the Editor, James Morris, Colonial Times (Hobart), 13 June 1843, page 3.

- Cash & Co., Launceston Advertiser, 15 June 1843, page 3.

- Mick Roberts (14 May 2015). "The Half Way House, Antill Ponds, Tasmania". Time Gents: Australian Pub Project. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- Cash, pages 94-96.

- The Bushrangers, The Courier (Hobart), 23 June 1843, page 2.

- Cash, pages 98-99.

- Cash & Co., Colonial Times (Hobart), 27 June 1843, page 3.

- Letter to the Editor, Samuel Smith, Austral-Asiatic Review, Tasmanian and Australian Advertiser (Hobart), 28 July 1843, page 4.

- Bushrangers, The Courier (Hobart), 30 June 1843, page 3.

- The Bushrangers, Teetotal Advocate (Launceston), 3 July 1843, page 2.

- The Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 4 July 1843, page 3.

- Cash, pages 101-103.

- Cash and Co., Teetotal Advocate (Launceston), 17 July 1843, page 3.

- The Bushrangers, The Courier (Hobart), 7 July 1843, page 3.

- Reward of One Hundred Acres of Land, or One Hundred Sovereigns!, The Courier (Hobart), 14 July 1843, page 4.

- Trial of George Jones The Notorious Bushranger, Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston), 24 April 1844, page 2; republished from the Hobart Town Advertiser.

- the Bushrangers, The Courier (Hobart), 14 July 1843, page 3.

- The Bushrangers, Launceston Examiner, 8 July 1843, page 6.

- Cash, pages 105-106.

- The Bushrangers, Colonial Times (Hobart), 18 July 1843, page 3.

- Centenary Of A Tasmanian Bushranger's Exploits, The Mercury (Hobart), 19 October 1943, page 7.

- Trial of Martin Cash, The Courier (Hobart), 8 September 1843, page 3.

- Trial of Lawrence Kavenagh, The Courier (Hobart), 15 September 1843, page 2.

- Cash, pages 103-104.

- Trial of Lawrence Kavenagh, The Courier (Hobart), 8 September 1843, page 3.

- Supreme Court. – Criminal Side, Colonial Times (Hobart), 19 September 1843, page 2.

- Supreme Court, Austral-Asiatic Review, Tasmanian and Australian Advertiser, (Hobart), 22 September 1843, page 3.

- Kavenagh, The Courier (Hobart), 22 September 1843, page 2.

- The Bushrangers, Launceston Examiner, 30 September 1843, page 3.

- "R. v. Cash; R. v. Kavenagh". Decisions of the Nineteenth Century Tasmanian Superior Courts (archived). Division of Law, Macquarie University & School of History and Classics, University of Tasmania. Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2021.; refer specifically to the ‘Notes’ at the foot of the webpage.

- Hazzard, page 183.

- Prisoners for Norfolk Island, Launceston Advertiser, 25 April 1844, page 2.

- Hobart Town, Shipping Gazette and Sydney General Trade List, 11 May 1844, page 59.

- Norfolk Island, Colonial Times (Hobart), 30 April 1844, page 3.

- Chapter of Old Times: Murderous Outbreak of Convicts on Norfolk Island, written by 'Flying Fish', Launceston Examiner, 12 June 1888, page 3.

- Hazzard, pages 193-194.

- Cash, the Bushranger, Colonial Times (Hobart), 3 December 1844, page 3.

- Norfolk Island, Tasmanian and Austral-Asiatic Review (Hobart), 27 February 1845, page 6.

- Cash, pages 121-123.

- Cash, pages 126-127.

- Hazzard, page 199; evidence by William Foster in the Report of the Commission held on Norfolk Island, 1 July 1846.

- Hazzard, pages 197-198; evidence by Patrick Hiney in the Report of the Commission held on Norfolk Island, 1 July 1846.

- Cash, page 128.

- Hazzard, page 198.

- Rev. Beagley Naylor, a clergyman on Norfolk Island, described Barrow as "a bumptious brutal fellow whose arbitrary assertions of authority... caused great resentment among the free officials"; quoted in Hazzard, page 194.

- Murder at Norfolk Island, Colonial Times (Hobart), 25 August 1846, page 3.

- Hazzard, pages 199-203.

- Hazzard, page 204.

- Norfolk Island, The Courier (Hobart), 4 July 1846, page 2.

- Norfolk Island, The Courier (Hobart), 2 September 1846, page 2.

- Norfolk Island, Geelong Advertiser and Squatters’ Advocate, 23 September 1846, page 1; reprinted from the Hobart Town Advertiser.

- Cash, pages 129-130.

- Chapter of Old Times No. 3, written by ‘Flying Fish’, Launceston Examiner, 7 July 1888, page 3.

- Hazzard, page 205.

- Norfolk Island, The Australian (Sydney), 14 November 1846, page 3.

- Norfolk Island – The Executions, The Australian (Sydney), 28 November 1846, page 3.

- "A Mystery Ship". The World of Norfolk’s Museum. Norfolk Island Museum. 14 September 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- "Murderers Mound, Kingston, Norfolk Island". Australian Cemeteries. Peter Applebee. 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

Sources

- Martin Cash (edited by James Lester Burke), The Adventures of Martin Cash, Comprising a Faithful Account of His Exploits, While a Bushranger under Arms in Tasmania, in Company with Kavanagh and Jones in the Year 1843; Hobart Town: "Mercury" Steam Press Office, 1870.

- Margaret Hazzard, Punishment Short of Death: a history of the penal settlement at Norfolk Island, Melbourne, Hyland, 1984. (ISBN 0-908090-64-1)

- J. E. Hiener; W. Hiener (1967). "Martin Cash: The Legend and the Man". Tasmanian Historical Research Association. 14 (2): 65–85.

A paper read to the Association on 11 May 1965.