Khajuraho Group of Monuments

The Khajuraho Group of Monuments are a group of Hindu and Jain temples in Chhatarpur district, Madhya Pradesh, India. They are about 175 kilometres (109 mi) southeast of Jhansi, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Khajwa, 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) from Rajnagar, and 49 kilometres (30 mi) from district headquarter Chhatarpur. The temples are famous for their Nagara-style architectural symbolism and a few erotic sculptures.[1]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Chhatarpur, Madhya Pradesh, India |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii |

| Reference | 240 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

| Coordinates | 24°51′16″N 79°55′17″E |

Location in Madhya Pradesh state of India  Khajuraho Group of Monuments (Madhya Pradesh) | |

Most Khajuraho temples were built between 885 CE and 1000 CE by the Chandela dynasty.[2][3] Historical records note that the Khajuraho temple site had 85 temples by the 12th century, spread over 20 square kilometres (7.7 sq mi). Of these, only about 25 temples have survived, spread over six square kilometres (2.3 sq mi).[3] Of the surviving temples, the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple is decorated with a profusion of sculptures with intricate details, symbolism, and expressiveness of ancient Indian art.[4] The temple complex was forgotten and overgrown by the jungle until 1838 when Captain T.S. Burt, a British engineer, visited the complex and reported his findings in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal.[5]

When these monuments were built, the boys in the place lived in hermitages, by being brahmacharyas (bachelors) until they attained manhood and these sculptures helped them to learn about the worldly role of 'householder'.[6] The Khajuraho group of temples were built together but were dedicated to two religions, Hinduism and Jainism, suggesting a tradition of acceptance and respect for diverse religious views among Hindus and Jains in the region.[7] Because of their outstanding architecture, diversity of temple forms, and testimony to the Chandela civilization, the monuments at Khajuraho were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1986.[8][3]

Location

The Khajuraho monuments are located in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, in Chatarpur district, about 620 kilometres (385 mi) southeast of New Delhi. The temples are located near a small town also known as Khajuraho,[9] with a population of about 24,481 people (2011 Census).

Khajuraho is served by Civil Aerodrome Khajuraho (IATA Code: HJR), with services to Delhi, Agra, Varanasi and Mumbai.[10] The site is also linked by the Indian Railways service, with the railway station located approximately six kilometres from the entrance to the monuments.

The monuments are about ten kilometres off the east-west National Highway 75, and about 50 kilometres from the city of Chhatarpur, which is connected to the state capital Bhopal by the SW-NE running National Highway 86.

The 10th-century Bhand Deva Temple in Rajasthan was built in the style of the Khajuraho monuments and is often referred to as 'Little Khajuraho'.

History

The Khajuraho group of monuments was built during the rule of the Chandela dynasty. The building activity started almost immediately after the rise of their power, throughout their kingdom to be later known as Bundelkhand.[11] Most temples were built during the reigns of the Hindu kings Yashovarman and Dhanga. Yashovarman's legacy is best exhibited by the Lakshmana Temple. Vishvanatha temple best highlights King Dhanga's reign.[12]: 22 The largest and currently most famous surviving temple is Kandariya Mahadeva built in the reign of King Vidyadhara.[13] The temple inscriptions suggest many of the currently surviving temples were complete between 970 and 1030 AD, with further temples completed during the following decades.[7]

The Khajuraho temples were built about 35 miles from the medieval city of Mahoba,[14] the capital of the Chandela dynasty, in the Kalinjar region. In ancient and medieval literature, their kingdom has been referred to as Jijhoti, Jejahoti, Chih-chi-to and Jejakabhukti.[15]

The first documented mention of Khajuraho was made in 641 by Xuanzang, a Chinese pilgrim who described encountering several dozen inactive Buddhist monasteries and a dozen Hindu temples with a thousand worshipping brahmins.[16] In 1022 CE, Khajuraho was mentioned by Abu Rihan-al-Biruni, the Persian historian who accompanied Mahmud of Ghazni in his raid of Kalinjar; he mentions Khajuraho as the capital of Jajahuti.[17] The raid was unsuccessful, and a peace accord was reached when the Hindu king agreed to pay a ransom to Mahmud of Ghazni to end the attack and leave.[15]

Khajuraho temples were in active use through the end of the 12th century. This changed in the 13th century; after the army of Delhi Sultanate, under the command of the Muslim Sultan Qutb-ud-din Aibak, attacked and seized the Chandela kingdom. About a century later, Ibn Battuta, the Moroccan traveller in his memoirs about his stay in India from 1335 to 1342 AD, mentioned visiting Khajuraho temples, calling them "Kajarra"[18][19] as follows:

...near (Khajuraho) temples, which contain idols that have been mutilated by the Moslems, live a number of yogis whose matted locks have grown as long as their bodies. And on account of extreme asceticism they are all yellow in colour. Many Moslems attend these men in order to take lessons (yoga) from them.

The central Indian region, where Khajuraho temples are, was controlled by various Muslim dynasties from the 13th century through the 18th century. In this period, some temples were desecrated, followed by a long period when they were left in neglect.[7][11] In 1495 CE, for example, Sikandar Lodi's campaign of temple destruction included Khajuraho.[21] The remoteness and isolation of Khajuraho protected the Hindu and Jain temples from continued destruction by Muslims.[22][23] Over the centuries, vegetation and forests overgrew the temples.

In the 1830s, local Hindus guided a British surveyor, T.S. Burt, to the temples and they were thus rediscovered by the global audience.[24] Alexander Cunningham later reported, few years after the rediscovery, that the temples were secretly in use by yogis and thousands of Hindus would arrive for pilgrimage during Shivaratri celebrated annually in February or March based on a lunar calendar. In 1852, F.C. Maisey prepared earliest drawings of the Khajuraho temples.[25]

Nomenclature

The name Khajuraho, or Kharjuravāhaka, is derived from ancient Sanskrit (kharjura, खर्जूर means date palm,[26] and vāhaka, वाहक means "one who carries" or bearer[27]). Local legends state that the temples had two golden date-palm trees as their gate (missing when they were rediscovered). Desai states that Kharjuravāhaka also means scorpion bearer, which is another symbolic name for deity Shiva (who wears snakes and scorpion garlands in his fierce form).[28]

Cunningham's nomenclature and systematic documentation work in 1850s and 1860s have been widely adopted and continue to be in use.[25] He grouped the temples into the Western group around Lakshmana, Eastern group around Javeri, and Southern group around Duladeva.[29]

Description

The temple site is within Vindhya mountain range in central India. An ancient local legend held that Hindu deity Shiva and other gods enjoyed visiting the dramatic hill formation in Kalinjar area.[29] The center of this region is Khajuraho, set midst local hills and rivers. The temple complex reflects the ancient Hindu tradition of building temples where gods love to pray.[29][30]

The temples are clustered near water, another typical feature of Hindu temples. The current water bodies include Sib Sagar, Khajur Sagar (also called Ninora Tal) and Khudar Nadi (river).[31] Local legends state that the temple complex had 64 water bodies, of which 56 have been physically identified by archeologists so far.[29][32]

All temples, except[29] one (Chaturbhuja) face the sunrise – another symbolic feature that is predominant in Hindu temples. The relative layout of temples integrate masculine and feminine deities and symbols highlight the interdependence.[33] The artworks symbolically highlight the four goals of life considered necessary and proper in Hinduism – dharma, kama, artha and moksha.

Of the surviving temples, six are dedicated to Shiva, eight to Vishnu and his affinities, one to Ganesha, one to Sun god, three to Jain Tirthankars.[29] For some ruins, there is insufficient evidence to assign the temple to specific deities with confidence.

An overall examination of site suggests that the Hindu symbolic mandala design principle of square and circles is present each temple plan and design.[34] Further, the territory is laid out in three triangles that converge to form a pentagon. Scholars suggest that this reflects the Hindu symbolism for three realms or trilokinatha, and five cosmic substances or panchbhuteshvara.[29] The temple site highlights Shiva, the one who destroys and recycles life, thereby controlling the cosmic dance of time, evolution and dissolution.[33]

The temples have a rich display of intricately carved statues. While they are famous for their erotic sculpture, sexual themes cover less than 10% of the temple sculpture.[35] Further, most erotic scene panels are neither prominent nor emphasized at the expense of the rest, rather they are in proportional balance with the non-sexual images.[36] The viewer has to look closely to find them, or be directed by a guide.[37] The arts cover numerous aspects of human life and values considered important in the Hindu pantheon. Further, the images are arranged in a configuration to express central ideas of Hinduism. All three ideas from Āgamas are richly expressed in Khajuraho temples – Avyakta, Vyaktavyakta and Vyakta.[38]

The Beejamandal temple is under excavation. It has been identified with the Vaidyanath temple mentioned in the Grahpati Kokalla inscription.[39]

Of all temples, the Matangeshvara temple remains an active site of worship.[33] It is another square grid temple, with a large 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) high and 1.1 metres (3.6 ft) diameter lingam, placed on a 7.6 metres (25 ft) diameter platform.[29]

The most visited temple, Kandariya Mahadev, has an area of about 6,500 square feet and a shikhara (spire) that rises 116 feet.[11][29]

Jain temples

The Jain temples are located on east-southeast region of Khajuraho monuments.[40] Chausath yogini temple features 64 yogini, while Ghantai temple features bells sculptured on its pillars.

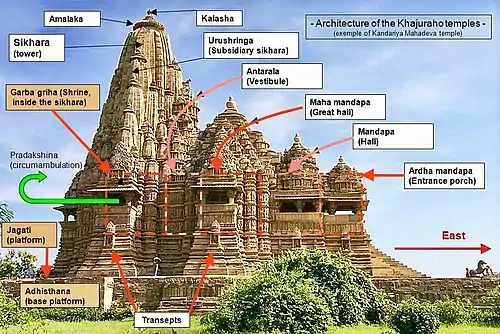

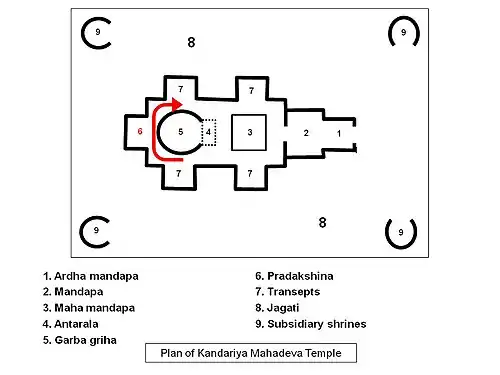

Architecture of the temples

Khajuraho temples, almost all Hindu temple designs, follow a grid geometrical design called vastu-purusha-mandala.[42] This design plan has three important components – Mandala means circle, Purusha is universal essence at the core of Hindu tradition, while Vastu means the dwelling structure.[43]

The design lays out a Hindu temple in a symmetrical, concentrically layered, self-repeating structure around the core of the temple called garbhagriya, where the abstract principle Purusha and the primary deity of the temple dwell. The shikhara, or spire, of the temple rises above the garbhagriya. This symmetry and structure in design is derived from central beliefs, myths, cardinality and mathematical principles.[44]

The circle of mandala circumscribe the square. The square is considered divine for its perfection and as a symbolic product of knowledge and human thought, while circle is considered earthly, human and observed in everyday life (moon, sun, horizon, water drop, rainbow). Each supports the other.[30] The square is divided into perfect 64 sub-squares called padas.[42]

Most Khajuraho temples deploy the 8x8 (64) padas grid Manduka Vastupurushamandala, with pitha mandala the square grid incorporated in the design of the spires.[41] The primary deity or lingas are located in the grid's Brahma padas.

The architecture is symbolic and reflects the central Hindu beliefs through its form, structure, and arrangement of its parts.[46] The mandapas, as well as the arts, are arranged in the Khajuraho temples in a symmetric repeating patterns, even though each image or sculpture is distinctive in its own way. The relative placement of the images are not random but together they express ideas, just like connected words form sentences and paragraphs to compose ideas.[47] This fractal pattern that is common in Hindu temples.[48] Various statues and panels have inscriptions. Many of the inscriptions on the temple walls are poems with double meanings, something that the complex structure of Sanskrit allows in creative compositions.[28]

All Khajuraho temples, except one, face sunrise, and the entrance for the devotee is this east side.

.jpg.webp)

Above the vastu-purusha-mandala of each temple is a superstructure with a dome called Shikhara (or Vimana, Spire).[43] Variations in spire design come from variation in degrees turned for the squares. The temple Shikhara, in some literature, is linked to mount Kailash or Meru, the mythical abode of the gods.[30]

In each temple, the central space typically is surrounded by an ambulatory for the pilgrim to walk around and ritually circumambulate the Purusa and the main deity.[30] The pillars, walls, and ceilings around the space, as well as outside have highly ornate carvings or images of the four just and necessary pursuits of life – kama, artha, dharma, and moksa. This clockwise walk around is called pradakshina.[43]

Larger Khajuraho temples also have pillared halls called mandapa. One near the entrance, on the east side, serves as the waiting room for pilgrims and devotees. The mandapas are also arranged by principles of symmetry, grids, and mathematical precision. This use of same underlying architectural principle is common in Hindu temples found all over India.[49] Each Khajuraho temple is distinctly carved yet also repeating the central common principles in almost all Hindu temples, one which Susan Lewandowski refers to as "an organism of repeating cells".[50]

Construction

The temples are grouped into three geographical divisions: western, eastern and southern.

The Khajuraho temples are made of sandstone, with a granite foundation that is almost concealed from view.[51] The builders didn't use mortar: the stones were put together with mortise and tenon joints and they were held in place by gravity. This form of construction requires very precise joints. The columns and architraves were built with megaliths that weighed up to 20 tons.[52] Some repair work in the 19th Century was done with brick and mortar; however, these have aged faster than original materials and darkened with time, thereby seeming out of place.

The Khajuraho and Kalinjar region is home to superior quality of sandstone, which can be carved precisely. The surviving sculpture reflect fine details such as strands of hair, manicured nails, and intricate jewelry.

While recording the television show Lost Worlds (History Channel) at Khajuraho, Alex Evans recreated a stone sculpture under four feet that took about 60 days to carve in an attempt to develop a rough idea of how much work must have been involved.[53] Roger Hopkins and Mark Lehner also conducted experiments to quarry limestone which took 12 quarrymen 22 days to quarry about 400 tons of stone.[54] They concluded that these temples would have required hundreds of highly trained sculptors.

Chronology

The Khajuraho group of temples belong to Vaishnavism school of Hinduism, Saivism school of Hinduism and Jainism – nearly a third each. Archaeological studies suggest all three types of temples were under construction at about the same time in the late 10th century, and in use simultaneously. Will Durant states that this aspect of Khajuraho temples illustrates the tolerance and respect for different religious viewpoints in the Hindu and Jain traditions.[55] In each group of Khajuraho temples, there were major temples surrounded by smaller temples – a grid style that is observed to varying degrees in Hindu temples in Angkor Wat, Parambaran and South India.

The largest surviving Shiva temple is Khandarya Mahadeva, while the largest surviving Vaishnava group includes Chaturbhuja and Ramachandra.

Kandariya Mahadeva Temple plan is 109 ft in length by 60 ft, and rises 116 ft above ground and 88 ft above its own floor. The central padas are surrounded by three rows of sculptured figures, with over 870 statues, most being half life size (2.5 to 3 feet). The spire is a self-repeating fractal structure.

| Sequence | Modern temple name | Religion | Deity | Completed by (CE)[29][56] | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chausath Yogini | Hinduism | Devi, 64 Yoginis | 885 |

|

| 2 | Lalguan Mahadev | Hinduism | Shiva | 900 |

|

| 3 | Brahma Temple | Hinduism | Shiva | 925 |

|

| 4 | Lakshmana | Hinduism | Vaikuntha Vishnu | 939 | .jpg.webp)

|

| 5 | Varaha | Hinduism | Varaha | 950 | .jpg.webp)

|

| 6 | Parshvanatha | Jainism | Parshvanatha | 954 | _(8638423582).jpg.webp)

|

| 7 | Ghantai | Jainism | Adinatha | 960 |

|

| 8 | Mahishasuramardini | Hinduism | Parvati | 995 | |

| 9 | Vishvanatha | Hinduism | Shiva | 999 | .jpg.webp)

|

| 10 | Matangeshwar | Hinduism | Shiva | 1000 | .jpg.webp)

|

| 11 | Vishnu-Garuda | Hinduism | Vishnu | 1000 | |

| 12 | Beejamandal Temple ruins | Hinduism | Shiva | 1000 | |

| 13 | Ganesha | Hinduism | Shiva | 1000 | |

| 14 | Jagadambi | Hinduism | Devi Jagadambi | 1023 |

|

| 15 | Chitragupta | Hinduism | Chitragupta | 1023 | .jpg.webp)

|

| 16 | Adinath Temple | Jainism | Adinatha | 1027 |  |

| 17 | Shantinatha temple | Jainism | Shantinatha | 1027 | .jpg.webp)

|

| 18 | Kandariya Mahadeva (the largest temple) | Hinduism | Shiva | 1029 |

|

| 19 | Vamana | Hinduism | Vamana | 1062 |

|

| 20 | Javeri | Hinduism | Shiva | 1090 |

|

| 21 | Chaturbhuja | Hinduism | Vishnu | 1110 |

|

| 22 | Duladeo (Duladeva) | Hinduism | Shiva | 1125 |

|

Arts and sculpture

The Khajuraho temples feature a variety of artwork, of which 10% is sexual or erotic art outside and inside the temples. Some of the temples that have two layers of walls have small erotic carvings on the outside of the inner wall. Some scholars suggest these to be tantric sexual practices.[57] Other scholars state that the erotic arts are part of the Hindu tradition of treating kama as an essential and proper part of human life, and its symbolic or explicit display is common in Hindu temples.[4][58] James McConnachie, in his history of the Kamasutra, describes the sexual-themed Khajuraho sculptures as "the apogee of erotic art":

Twisting, broad-hipped and high breasted nymphs display their generously contoured and bejewelled bodies on exquisitely worked exterior wall panels. These fleshy apsaras run riot across the surface of the stone, putting on make-up, washing their hair, playing games, dancing, and endlessly knotting and unknotting their girdles. ... Beside the heavenly nymphs are serried ranks of griffins, guardian deities and, most notoriously, extravagantly interlocked maithunas, or lovemaking couples.

.jpg.webp)

The temples have several thousand statues and artworks, with Kandarya Mahadeva Temple alone decorated with over 870. Some 10% of these iconographic carvings contain sexual themes and various sexual poses. A common misconception is that, since the old structures with carvings in Khajuraho are temples, the carvings depict sex between deities;[59] however, the kama arts represent diverse sexual expressions of different human beings.[60] The vast majority of arts depict various aspects the everyday life, mythical stories as well as symbolic display of various secular and spiritual values important in Hindu tradition.[3][4] For example, depictions show women putting on makeup, musicians making music, potters, farmers, and other folks in their daily life during the medieval era.[61] These scenes are in the outer padas as is typical in Hindu temples.

There is iconographic symbolism embedded in the arts displayed in Khajuraho temples.[4] Core Hindu values are expressed in multitude of ways. Even the Kama scenes, when seen in combination of sculptures that precede and follow, depict the spiritual themes such as moksha. In the words of Stella Kramrisch,

This state which is "like a man and woman in close embrace" is a symbol of moksa, final release or reunion of two principles, the essence (Purusha) and nature (Prakriti).

— Stella Kramrisch, 1976[30]

The Khajuraho temples represent one expression of many forms of arts that flourished in Rajput kingdoms of India from 8th through 10th century CE. For example, contemporary with Khajuraho were the publications of poems and drama such as Prabodhacandrodaya, Karpuramanjari, Viddhasalabhanjika and Kavyamimansa.[62] Some of the themes expressed in these literary works are carved as sculpture in Khajuraho temples.[28][63] Some sculptures at the Khajuraho monuments dedicated to Vishnu include the Vyalas, which are hybrid imaginary animals with lions' bodies, and are found in other Indian temples.[64] Some of these hybrid mythical artwork include Vrik Vyala (hybrid of wolf and lion) and Gaja Vyala (hybrid of elephant and lion). These Vyalas may represent syncretic, creative combination of powers innate in the two.[65]

Tourism and cultural events

The temples in Khajuraho are broadly divided into three parts: the Eastern group, the Southern Group and the Western group of temples of which the Western group alone has the facility of an audio-guided tour wherein the tourists are guided through the seven-eight temples. There is also an audio guided tour developed by the Archaeological Survey of India which includes a narration of the temple history and architecture.[66]

The Khajuraho Dance Festival is held every year in February.[67] It features various classical Indian dances set against the backdrop of the Chitragupta or Vishwanath Temples.

The Khajuraho temple complex offers a son et lumière (sound and light) show every evening. The first show is in English language and the second, in Hindi. It is held in the open lawns in the temple complex, and has received mixed reviews.

See also

- List of megalithic sites

- Jain temples of Khajuraho

- Ajanta Caves

- Bhand Deva Temple, called the Little Khajuraho due to similar architecture

- Badami Chalukya architecture

- Western Chalukya architecture

- Hindu temple

- Madan Kamdev

- Hemvati

- Kama Sutra

- Kamashastra

Khajuraho travel guide from Wikivoyage

Khajuraho travel guide from Wikivoyage

References

- Philip Wilkinson (2008), India: People, Place, Culture and History, ISBN 978-1405329040, pp 352-353

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 179.

- "Khajuraho Group of Monuments". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 25 June 2023.

- Devangana Desai (2005), Khajuraho, Oxford University Press, Sixth Print, ISBN 978-0-19-565643-5

- Slaczka, Anna. “Temples, Inscriptions and Misconceptions: Charles-Louis Fábri and the Khajuraho ‘Apsaras.’” The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 60, no. 3 (2012): 212–33. See p. 217.

- Frontline, Volume 24, Issues 6-12. S. Rangarajan for Kasturi & Sons. 2007. p. 93.

- James Fergusson, Northern or Indo-Aryan Style - Khajuraho History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, Updated by James Burgess and R. Phene Spiers (1910), Volume II, John Murray, London

- "World Heritage Day: Five must-visit sites in India". 18 April 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015.

- "Census of India 2001: Data from the 2001 Census, including cities, villages and towns (Provisional)". Census Commission of India. Archived from the original on 16 June 2004. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Khajuraho airport Archived 8 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine AAI, Govt of India

- G.S. Ghurye, Rajput Architecture, ISBN 978-8171544462, Reprint Year: 2005, pp 19-24

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. ISBN 9789380607344.

- Devangana Desai 2005, p. 10.

- also called Erakana

- Mitra (1977), The early rulers of Khajuraho, ISBN 978-8120819979

- Hioco, Christophe; Poggi, Luca (2017). Khajuraho: Indian Temples and Sensuous Sculptures. 5 Continents Editions. p. 9. ISBN 978-88-7439-778-5.

- J. Banerjea (1960), Khajuraho, Journal of the Asiatic Society, Vol. 2-3, pp 43-47

- phonetically translated from Arabic sometimes as "Kajwara"

- Director General of Archaeology in India (1959), Archaeological Survey of India, Ancient India, Issues 15-19, pp 45-46 (Archived: University of Michigan)

- Arthur Cotterell (2011), Asia: A Concise History, Wiley, ISBN 978-0470825044, pp 184-185

- Michael D. Willis, An Introduction to the Historical Geography of Gopakṣetra, Daśārṇa, and Jejākadeśa, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 51, No. 2 (1988), pp. 271-278; See also K.R. Qanungo (1965), Sher Shah and his times, Orient Longmans, OCLC 175212, pp 423-427

- Trudy King et al., Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places, ISBN 978-1884964046, Routledge, pp 468-470

- Alain Daniélou (2011), A Brief History of India, ISBN 978-1594770296, pp 221-227

- Louise Nicholson (2007), India, National Geographic Society, ISBN 978-1426201448, see Chapter on Khajuraho

- Krishna Deva (1990), Temples of Khajuraho, 2 Volumes, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi

- kharjUra Sanskrit English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- vAhaka Sanskrit English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

- Devangana Desai (1996), Chapter 7 - Puns and Enigmatic Language in Sculpture Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine in The Religious Imagery of Khajuraho, Project for Indian Cultural Studies, Columbia University Archives

- Rana Singh (2007), Landscape of sacred territory of Khajuraho, in City Society and Planning (Editors: Thakur, Pomeroy, et al), Volume 2, ISBN 978-8180694585, Chapter 18

- Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple, Vol 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0222-3

- Ibn Battuta in his 1335 CE memoirs on Delhi Sultanate mentioned the temples to be near a mile-long lake, modern water bodies are much smaller and separate lagoons; Director General of Archaeology in India (1959), Archaeological Survey of India, Ancient India, Issues 15-19, pp 45-46 (Archived: University of Michigan)

- The number 64 is considered sacred in Hindu temple design and very common design basis; it is symbolic as it is both a square of 8 and a cube of 4.

- Shobita Punja (1992), Divine Ecstasy - The Story of Khajuraho, Viking, New Delhi, ISBN 978-0670840274

- Brahma temple is 19 feet square; Kandariya Mahadev has a four fused square grid; Matangeshvara temple is a 64 grid square; etc. See G.S. Ghurye, Rajput Architecture, ISBN 978-8171544462, Reprint Year: 2005, pp 19-25; and V.A. Smith (1879), "Observations on some Chandel Antiquities", Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. 48, Part 1, pp 291-297

- D Desai (1996), The religious imagery of Khajuraho, Project for Indian Cultural Studies, ISBN 978-8190018418

- Desai states that Khajuraho and Orissa Hindu temples are distinctive in giving erotic kama images the same weight as others and by assigning important architectural position; in contrast, surviving sculpture from temples of Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Mysore show that their kama and sexual images were assigned to insignificant parts of the temple; Meister suggests that this aspect of eroticism in temple design and equal weight reflects evolution of design ideas among Hindu artisans, with temples built in later medieval centuries placing equal weight and balance to kama; see Meister, Michael (1979). "Juncture and Conjunction: Punning and Temple Architecture". Artibus Asiae. 41 (2–3): 226–234. doi:10.2307/3249517. JSTOR 3249517.

- Edmund Leach, The Harvey Lecture Series. The Gatekeepers of Heaven: Anthropological Aspects of Grandiose Architecture, Journal of Anthropological Research, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn, 1983), pp 243-264

- Bettina Bäumer, A review, Artibus Asiae, Vol. 59, No. 1/2 (1999), pp. 138-140

- Cunningham, Alexander (1880). Report of Tours in Bundelkhand and Malwa in 1874-75 and 1876-77. 8 Hastings Street, Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing. p. 22. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - James Fergusson, Jaina Architecture - Khajuraho History of Indian and Eastern Architecture, Updated by James Burgess and R. Phene Spiers (1910), Volume II, John Murray, London

- Meister, Michael W. (April–June 1979). "Maṇḍala and Practice in Nāgara Architecture in North India". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 99 (2): 204–219. doi:10.2307/602657. JSTOR 602657.

- Meister, Michael (1983). "Geometry and Measure in Indian Temple Plans: Rectangular Temples". Artibus Asiae. 44 (4): 266–296. doi:10.2307/3249613. JSTOR 3249613.

- Susan Lewandowski, The Hindu Temple in South India, in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (Editor), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, pp 68-69

- Stella Kramrisch (1976), The Hindu Temple Volume 1, ISBN 81-208-0223-3

- Meister, Michael W. (March 2006). "Mountain Temples and Temple-Mountains: Masrur". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 65 (1): 26–49. doi:10.2307/25068237. JSTOR 25068237.

- Meister, Michael W. (Autumn 1986). "On the Development of a Morphology for a Symbolic Architecture: India". RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. 12 (12): 33–50. doi:10.1086/RESv12n1ms20166752. JSTOR 20166752. S2CID 132490349.

- Devangana Desai, Khajuraho, Oxford University Press Paperback (Sixth impression 2005) ISBN 978-0-19-565643-5

- Rian et al (2007), Fractal geometry as the synthesis of Hindu cosmology in Kandariya Mahadev Temple, Khajuraho, Building and Environment, Vol 42, Issue 12, pp 4093-4107, doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2007.01.028

- Trivedi, K. (1989). Hindu temples: models of a fractal universe. The Visual Computer, 5(4), 243-258

- Susan Lewandowski, The Hindu Temple in South India, in Buildings and Society: Essays on the Social Development of the Built Environment, Anthony D. King (Editor), ISBN 978-0710202345, Routledge, Chapter 4

- V.A. Smith, "Observations on some Chandel Antiquities", Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume 48, pp 290-291

- "Lost Worlds of the Kama Sutra" History channel

- "Lost Worlds of the Kama Sutra," History Channel

- Lehner, Mark (1997) The Complete Pyramids, London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05084-8. pp. 202–225

- Will Durant (1976), Our Oriental Heritage: The Story of Civilization, ISBN 978-0671548001, Simon & Schuster

- From inscription or estimated from other evidence

- Rabe (2000), Secret Yantras and Erotic Display for Hindu Temples, Tantra in Practice (Editor: David White), ISBN 978-8120817784, Chapter 25, pp 434-446

- See:

- "Khajuraho". Liveindia.com. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Alain Danielou (2001), The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism, ISBN 978-0892818549

- George Michell, The Hindu Temple: An Introduction to Its Meaning and Forms, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226532301, pp 117-123 and pp 56–58

- L. H. Gray, Journal of American Society, Vol. 27

- H. W. Woodward (1989), "The Lakṣmaṇa Temple, Khajuraho, and Its Meanings", Ars Orientalis, Vol. 19, pp. 27–48

- Smith, David (1 January 2013). "Monstrous Animals on Hindu Temples, with Special Reference to Khajuraho". Religions of South Asia. 7 (1–3): 27–43. doi:10.1558/rosa.v7i1-3.27.

- Hiram W. Woodward, Jr., "The Lakṣmaṇa Temple, Khajuraho, and Its Meanings", Ars Orientalis, Vol. 19, (1989), pp. 27–48

- Tourists to Khajuraho will now have an audio compass The Times of India (25 August 2011)

- "Khajuraho Festival of Dances". Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

Further reading

- Project Love Temple (Machines, Myths, and Miracles): a sci-fi book based on Temples of Khajuraho

- M.R. Anand and Stella Kramrisch, Homage to Khajuraho, OCLC 562891704

- Alain Daniélou, The Hindu Temple: Deification of Eroticism, ISBN 978-0892818549

- Prasenjit Dasgupta, Khajuraho, Patralekha, Kolkata, 2014

- Devangana Desai, The Religious Imagery of Khajuraho, Franco-Indian Research P. Ltd. (1996) ISBN 81-900184-1-8

- Devangana Desai (2005). Khajuraho (Sixth impression ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-565391-5.

- Phani Kant Mishra, Khajuraho: With Latest Discoveries, Sundeep Prakashan (2001) ISBN 81-7574-101-5

- L. A. Narain, Khajuraho: Temples of Ecstasy. New Delhi: Lustre Press (1986)

External links

![]() Khajuraho travel guide from Wikivoyage

Khajuraho travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Khajuraho Group of Monuments UNESCO

- Archaeological Survey of India, Bhopal Division

- R. Nath Mughal Architecture Image Collection, Images of Khajuraho - University of Washington Digital Collection

- Chatr ko putr Chitragupta temple at Khujraho in 1882

- Project Love Temple : a sci-fi book based on Temples of Khajuraho