Historic City of Ahmadabad

The Historic City of Ahmadabad or Old Ahmedabad, the walled city of Ahmedabad in India, was founded by Ahmad Shah I of the Gujarat Sultanate in 1411. It remained the capital of the state of Gujarat for six centuries and later became the important political and commercial centre of Gujarat. Today, despite having become crowded and dilapidated, it still serves as the symbolic heart of metropolitan Ahmedabad. It was inscribed as the World Heritage City by UNESCO in July 2017.[1]

Historic City of Ahmadabad

અમદાવાદ કોટવિસ્તાર | |

|---|---|

Urban settlement | |

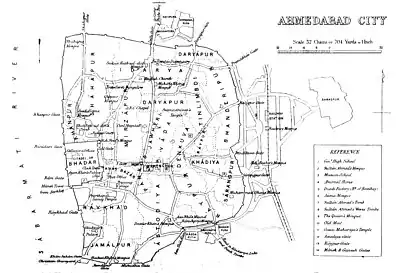

Map of old Ahmedabad in 1855 | |

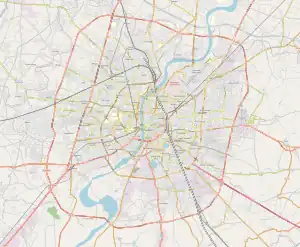

Historic City of Ahmadabad Location in Gujarat, India  Historic City of Ahmadabad Historic City of Ahmadabad (Gujarat)  Historic City of Ahmadabad Historic City of Ahmadabad (India) | |

| Coordinates: 23°1′32″N 72°35′15″E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Gujarat |

| District | Ahmedabad district |

| City | Ahmedabad |

| Established | 1411 |

| Founded by | Ahmad Shah I |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (v) |

| Reference | 1551 |

| Inscription | 2017 (41st Session) |

| Area | 535.7 ha (2.068 sq mi) |

| Buffer zone | 395 ha (1.53 sq mi) |

History

The earliest settlements were situated south of the current old city and on the bank of Sabarmati river. It was known as Ashaval or Ashapalli. In the 11th century, Karna of the Chaulukya dynasty made the town his capital and named it Karnavati (Karna's town), Shrinagar (prosperous city), and Rajnagar (king's town).[2]

Ahmed Shah I laid the foundation of Bhadra Fort starting from Manek Burj, the first bastion of the city in 1411 which was completed in 1413. He also established the first square of the city, Manek Chowk, both associated with the legend of Hindu saint Maneknath. His Gujarat Sultanate (1411-1573) ruled from the city until 1484. His grandson Mahmud Begada transferred capital from Ahmedabad to Muhammadabad from 1484 to 1535 but carried out second fortification of the city. Later Ahmedabad again became capital of sultanate until it fell to Mughals in 1573. During Mughal rule (1572-1707), Bhadra Fort served as the seat of Governor of Gujarat. The city flourished with addition of several settlements in and around the city. Of the population of the city no estimate has been traced. There is some estimate of the size of city in works of the time: Ferishta, the Ain-i-Akbari, and the Mirat-i-Ahmadi. According to the Ain-i-Akbari (1580), there were 360 puras, of which only eighty-four were then flourishing; according to Ferishta there were, in 1600, 360 mahalla, each surrounded by a wall ; the Mirat-i-Ahmadi in one passage says, such was once its populous state that it contained 380 puras, each pura a considerable quarter almost a city; in another passage he mentions twelve city wards and others outside, and in his detailed account of the city he mentions by name 110 suburbs of which 19 were settled under Mughal rule. German traveller Mandelslo (1638) mentioned the suburbs and dependent villages are nearly seven leagues round.[3] During Mughal and Maratha struggle (1707–1753) to control the city, the city was harmed and several suburbs were depopulated. The city walls damaged in battles and the trade was affected. The city revenue was divided between Mughal and Maratha rulers. Later during Maratha rule (1758–1817), the city revenue was divided between Peshwa and Gaekwad. These affected the economy of the city due to more extraction of taxes. In 1817, Ahmedabad fell under British Company rule which stabilized the city politically and improved the trade. The population rose from 80,000 in 1817 to about 88,000 in 1824. During the eight following years a special cess was levied on ghee and other products and at a cost of £25,000 (Rs. 2,50,000) the city walls were repaired. About the same time a cantonment was established on a site to the north of the city. The population rose (1816) to about 95,000. The remaining public funds after the walls were finished were used for municipal purposes.[4] The old city continued to be the centre of political activities during the Indian independence movement under Mahatma Gandhi.

Forts and Gates

Forts

Square in form, enclosing an area of about forty-three acres, the Bhadra fort had eight gates, three large, two in the east and one in the south-west corner; three middle-sized, two in the north and one in the south; and two small, in the west. The construction of Jama Masjid, Ahmedabad completed in 1423. As the city expanded, the city wall was expanded. So the second fortification was carried out by Mahmud Begada in 1486, the grandson of Ahmed Shah, with an outer wall 10 km (6.2 mi) in circumference and consisting of 12 gates, 189 bastions and over 6,000 battlements as described in Mirat-i-Ahmadi.[5] The city walls of second fortification, running on the west for about a mile and three quarters along the bank of the Sabarmati, and stretching east in semi-circular form, include an area of two square miles in past.[6]

Gates

Most people believe that Ahmedabad had 12 gates but some historian suggested to have 16. Later some Indologist found that Ahmedabad had 21 gates. Bhadra fort had eight gates, three large, two in the east and one in the south-west corner; three middle-sized, two in the north and one in the south; and two small, in the west.[7] In the city walls of second fort, there were eighteen gates, fifteen large and three small. Of the fifteen, one was closed, and two were added later. These gates were, beginning from the north-west corner, three in the north-wall, the Shahpur in the north-west, the Delhi in the north, and the Dariyapur in the north-east; four in the east wall, the Premabhai, a gate built by British, in the north-east, the Kalupur in the east, the Panchkuva, a gate built by British, in the east, and the Sarangpur in the south-east; four in the south wall, the Raipur and Astodiya in the south-east, and the Mahuda, the closed gate, and the Jamalpur in the south; seven in the west wall, the Khan Jahan, Raikhad and Manek in the south-west; the three citadel gates, Ganesh, Ram, and Baradari in the centre; and the Khanpur gate in the north-west.[8][9] Two new gates, Prem Darwaja and Panchkuva Gate added by British after opening of railways in 1864.[10]

Neighbourhood

Pols were the typical housing cluster of the old city with there being as many as 356 in 1872. This form of housing was established during a time of divided rule from 1738-1753 due to religious tension between Hindu and Muslims. When the city walls deteriorated and no longer provided protection from robbers, the pol gate became more important for protection.[11]

Architecture

The old city features rich wooden architecture, havelis, khadkis, and pols. The wooden architecture is exemplary of the unique heritage and culture in Ahmedabad. It signifies contributions to arts and crafts, traditions, and structure design, and is reflective of the city's occupants. The city's architecture was designed to promote a sense of community, family, and multiculturalism. This is evident in the city being home to institutions belonging to several religions including Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism.[12]

References

- "Ahmedabad takes giant leap, becomes India's first World Heritage City". The Times of India. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- Google Books 2015, p. 249.

- Google Books 2015, p. 252-253.

- Google Books 2015, pp. 260–261.

- G. Kuppuram (1988). India through the ages: history, art, culture, and religion. Vol. 2. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 739. ISBN 9788185067094.

- Google Books 2015, p. 248.

- Rajput, Vipul; Patel, Dilip (8 February 2010). "City's Lost Gates". Ahmedabad Mirror. AM. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- Pandya, Yatin (23 January 2011). "Ahmedabad gates: Residue of past or the pride of the present?". DNA. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Ahmedabad. Government Central Press. 1879. pp. 273–277.

- Google Books 2015, p. 262.

- Google Books 2015, p. 294-295.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Historic City of Ahmadabad". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

Bibliography

- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency: Ahmedabad. 7 January 2015. pp. 248–262. Retrieved 1 February 2015 – via Google Books 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.