Kaziranga National Park

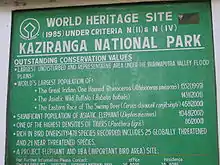

Kaziranga National Park is a national park in the Golaghat and Nagaon districts of the state of Assam, India. The park, which hosts two-thirds of the world's Indian rhinoceroses, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[2] According to the census held in March 2018 which was jointly conducted by the Forest Department of the Government of Assam and some recognized wildlife NGOs, the rhino population in Kaziranga National Park is 2,613. It comprises 1,641 adult rhinos (642 males, 793 females, 206 unsexed); 387 sub-adults (116 males, 149 females, 122 unsexed); and 385 calves.[3]

| Kaziranga National Park | |

|---|---|

Adult Indian rhinoceros, with a calf at Kaziranga National Park in Bagori range of Nagaon district of Assam, India | |

| |

| Location | Golaghat and Nagaon districts[1] |

| Nearest city | Golaghat |

| Coordinates | 26°40′N 93°21′E |

| Area | 1,090 km2 (420 sq mi) |

| Established | 1905 1974 (as national park) |

| Governing body | Government of Assam Government of India , |

| World Heritage site | World Heritage Place by UNESCO since 1985 , https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/337/ |

| forest | |

In 2015, the rhino population stood at 2401. Kaziranga National Park was declared a Tiger Reserve in 2006. The park is home to large breeding populations of elephants, wild water buffalo, and swamp deer.[4] Kaziranga is recognized as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International for conservation of avifaunal species. When compared with other protected areas in India, Kaziranga has achieved notable success in wildlife conservation. Located on the edge of the Eastern Himalaya biodiversity hotspot, the park combines high species diversity and visibility.

Kaziranga is a vast expanse of tall elephant grass, marshland, and dense tropical moist broadleaf forests, criss-crossed by four major rivers, including the Brahmaputra, and the park includes numerous small bodies of water. Kaziranga has been the theme of several books, songs, and documentaries. The park celebrated its centennial in 2005 after its establishment in 1905 as a reserve forest.

In 2017, Kaziranga came under severe criticism after a BBC News documentary revealed a hardliner strategy to conservation, reporting the killing of 20 people a year in the name of rhino conservation.[5] As a consequence of this reporting, BBC News was banned from filming in protected areas in India for 5 years.[6] While several news reports claimed that BBC had apologized for the documentary, the BBC stood by its report, with its Director General, Tony Hall, writing in a letter to Survival International that the letter "in no way constitutes an apology for our journalism."[7] As a response to the report, researchers in India have provided more nuanced understanding of the matter, calling out BBC for the carelessness of its journalism, but also pointing to the problems of conservation in Kaziranga[8] and questioning whether shoot-at-sight has been a useful conservation strategy at all.[9]

History of Kaziranga National Park

The history of Kaziranga as a protected area can be traced back to 1904, when Mary Curzon, Baroness Curzon of Kedleston, the wife of the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon of Kedleston, visited the area.[10] After failing to see a single-horned rhinoceros, for which the area was renowned, she persuaded her husband to take urgent measures to protect the dwindling species which he did by initiating planning for their protection.[11] On 1 June 1905, the Kaziranga Proposed Reserve Forest was created with an area of 232 km2 (90 sq mi).[12]

Over the next three years, the park area was extended by 152 km2 (59 sq mi), to the banks of the Brahmaputra River.[13] In 1908, Kaziranga was designated a "Reserve Forest".

In 1916, it was redesignated the "Kaziranga Game Sanctuary" and remained so till 1938, when hunting was prohibited and visitors were permitted to enter the park.. In 1934 Kaziranga was changed to Kaziranha. A few people call it by its original name till today.

The Kaziranga Game Sanctuary was renamed the "Kaziranga Wildlife Sanctuary" in 1950 by P. D. Stracey, the forest conservationist, in order to rid the name of hunting connotations.[14]

In 1954, the government of Assam passed the Assam (Rhinoceros) Bill, which imposed heavy penalties for rhinoceros poaching. Fourteen years later, in 1968, the state government passed the Assam National Park Act of 1968, declaring Kaziranga a designated national park. The 430 km2 (166 sq mi) park was given official status by the central government on 11 February 1974. In 1985, Kaziranga was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO for its unique natural environment.

Kaziranga has been the target of several natural and man-made calamities in recent decades. Floods caused by the overflow of the river Brahmaputra, leading to significant losses of animal life.[15] Encroachment by people along the periphery has also led to a diminished forest cover and a loss of habitat. An ongoing separatist movement in Assam led by the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) has crippled the economy of the region,[16] but Kaziranga has remained unaffected by the movement; indeed, instances of rebels from the United Liberation Front of Assam protecting the animals and, in extreme cases, killing poachers, have been reported since the 1980s.[11]

Etymology

Although the etymology of the name Kaziranga is not certain, there exist a number of possible explanations derived from local legends and records. According to one legend, a girl named Rawnga, from a nearby village, and a youth named Kazi, from Karbi Anglong, fell in love. This match was not acceptable to their families, and the couple disappeared into the forest, never to be seen again, and the forest was named after them. According to another legend, Srimanta Sankardeva, the sixteenth-century Vaisnava saint-scholar, once blessed a childless couple, Kazi and Rangai, and asked them to dig a big pond in the region so that their name would live on.[17]

Testimony to the long history of the name can be found in some records, which state that once, while the Ahom king Pratap Singha was passing by the region during the seventeenth century, he was particularly impressed by the taste of fish, and on asking was told it came from Kaziranga.[18] Kaziranga also could mean the "Land of red goats (Deer)", as the word Kazi in the Karbi language means "goat", and Rangai means "red".[18]

Some historians believe, however, that the name Kaziranga was derived from the Karbi word Kajir-a-rong, which means "the village of Kajir" (kajiror gaon). Among the Karbis, Kajir is a common name for a girl child, and it was believed that a woman named Kajir once ruled over the area. Fragments of monoliths associated with Karbi rule found scattered in the area seem to bear testimony to this assertion.

Grassland of Kaziranga National Park

Grassland of Kaziranga National Park Rhinos grazing in the grassland of Kaziranga

Rhinos grazing in the grassland of Kaziranga

Geography

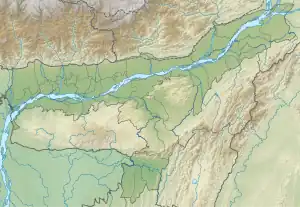

Kaziranga is located between latitudes 26°30' N and 26°45' N, and longitudes 93°08' E to 93°36' E within three districts in the Indian state of Assam—the Kaliabor subdivision of Nagaon district, Bokajan subdivision of Karbi Anglong and the Bokakhat subdivision of Golaghat district.[19]

The park is approximately 40 km (25 mi) in length from east to west, and 13 km (8 mi) in breadth from north to south.[20] Kaziranga covers an area of 378 km2 (146 sq mi), with approximately 51.14 km2 (20 sq mi) lost to erosion in recent years.[20] A total addition of 429 km2 (166 sq mi) along the present boundary of the park has been made and designated with separate national park status to provide extended habitat for increasing the population of wildlife or, as a corridor for safe movement of animals to Karbi Anglong Hills.[21] : p.06 Elevation ranges from 40 m (131 ft) to 80 m (262 ft). The park area is circumscribed by the Brahmaputra River, which forms the northern and eastern boundaries, and the Mora Diphlu, which forms the southern boundary. Other notable rivers within the park are the Diphlu and Mora Dhansiri.[22] : p.05

Kaziranga has flat expanses of fertile, alluvial soil, formed by erosion and silt deposition by the River Brahmaputra. The landscape consists of exposed sandbars, riverine flood-formed lakes known as, beels, (which make up 5% of the surface area), and elevated regions known as, chapories, which provide retreats and shelter for animals during floods. Many artificial chapories have been built with the help of the Indian Army to ensure the safety of the animals.[23][24] Kaziranga is one of the largest tracts of protected land in the sub-Himalayan belt, and due to the presence of highly diverse and visible species, has been described as a "biodiversity hotspot".[25] The park is located in the Indomalayan realm, and the dominant ecoregions of the region are Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests of the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome, and the frequently-flooded Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands of the tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome. Kaziranga is also surrounded by lush green tea plantations, most of them contributing heavily to Assam's economy.

Climate

The park experiences three seasons: summer, monsoon, and winter. The winter season, between November and February, is mild and dry, with a mean high of 25 °C (77 °F) and low of 5 °C (41 °F). During this season, beels and nullahs (water channels) dry up.[22]: p.06 The summer season between March and May is hot, with temperatures reaching a high of 37 °C (99 °F). During this season, animals usually are found near water bodies.[22]: p.06 The rainy monsoon season lasts from June to September, and is responsible for most of Kaziranga's annual rainfall of 2,220 mm (87 in).[26] During the peak months of July and August, three-fourths of the western region of the park is submerged, due to the rising water level of the Brahmaputra. It was found that 70% of the National Park was flooded as on 3 August 2016. The flooding causes most animals to migrate to elevated and forested regions outside the southern border of the park, such as the Mikir hills. 540 animals, including 13 rhinos and mostly hog deer perished in unprecedented floods of 2012.[19][27] However, occasional dry spells create problems as well, such as food shortages and occasional forest fires.[28]

Climate of Kaziranga National Park And Tiger Reserve

Kaziranga National Park has a tropical monsoon climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. The park experiences heavy rainfall during the monsoon season, which lasts from June to September, and dry conditions from November to March. The average annual rainfall in Kaziranga is around 2,200 mm (87 inches), For more

Fauna

Kaziranga contains significant breeding populations of 35 mammalian species,[29] of which 15 are threatened as per the IUCN Red List. The park has the distinction of being home to the world's largest population of the Indian rhinoceros (2,401),[30][31] wild water buffalo (1,666)[32] and eastern swamp deer (468).[33] Significant populations of large herbivores include Indian elephants (1,940),[34] gaur (1300) and sambar (58). Small herbivores include the chital, Indian muntjac, Indian boar and Indian hog deer.[19][35] Kaziranga has the largest population of the Wild water buffalo anywhere accounting for about 57% of the world population.[36] The Indian rhinoceros, royal Bengal tiger, Asian elephant, wild water buffalo and swamp deer are collectively known as 'Big Five' of Kaziranga.

Kaziranga is one of the few wild breeding areas outside Africa for multiple species of large cats, such as Bengal tigers and Indian leopard.[29] Kaziranga was declared a Tiger Reserve in 2006 and has the highest density of tigers in the world (1 per 5 km2), with a population of 118, according to the latest census.[30] Other felids include the jungle cat, fishing cat and leopard cat.[29] It is also the only place in India and the world, where a Golden tiger was spotted in the wild.[37]

Small mammals include the rare hispid hare, Indian gray mongoose, small Indian mongooses, large Indian civet, small Indian civets, Bengal fox, golden jackal, sloth bear, Chinese pangolin, Indian pangolins, hog badger, Chinese ferret-badger, and particoloured flying squirrel.[19][29] Nine of the 14 primate species found in India occur in the park.[11] Prominent among them are the Assamese macaque, capped and golden langur, as well as the only ape found in India, the hoolock gibbon.[19][29] Kaziranga's rivers are also home to the endangered Ganges dolphin.

Kaziranga has been identified by Birdlife International as an Important Bird Area.[38] It is home to a variety of migratory birds, water birds, predators, scavengers, and game birds. Birds such as the lesser white-fronted goose, ferruginous duck, Baer's pochard duck and lesser adjutant, greater adjutant, black-necked stork, and Asian openbill stork migrate from Central Asia to the park during winter.[39] Riverine birds include the Blyth's kingfisher, white-bellied heron, Dalmatian pelican, spot-billed pelican, Nordmann's greenshank, and black-bellied tern.[39]: p.10 Birds of prey include the rare eastern imperial, greater spotted, white-tailed, Pallas's fish eagle, grey-headed fish eagle, and the lesser kestrel.[40]

Kaziranga was once home to seven species of vultures, but the vulture population reached near extinction, supposedly by feeding on animal carcasses containing the drug Diclofenac.[41] Only the Indian vulture, slender-billed vulture, and white-rumped vulture have survived.[41] Game birds include the swamp francolin, Bengal florican, and pale-capped pigeon.[39]: p.03

Other families of birds inhabiting Kaziranga include the great pied hornbill and wreathed hornbill, Old World babblers such as Jerdon's and marsh babblers, weaver birds such as the common baya weaver, threatened Finn's weavers, thrushes such as Hodgson's bushchat and Old World warblers such as the bristled grassbird. Other threatened species include the black-breasted parrotbill and the rufous-vented grass babbler.[39]: p.07–13

Two of the largest snakes in the world, the reticulated python and Indian rock python, as well as the longest venomous snake in the world, the king cobra, inhabit the park. Other snakes found here include the Indian cobra, monocled cobra, Russell's viper, and the common krait.[29] Monitor lizard species found in the park include the Bengal monitor and the Asian water monitor.[29] Other reptiles include fifteen species of turtle, such as the endemic Assam roofed turtle and one species of tortoise, the brown tortoise.[29] 42 species of fish are found in the area, including the Tetraodon.[29]

Flora

Four main types of vegetation exist in this park.[42] These are alluvial inundated grasslands, alluvial savanna woodlands, tropical moist mixed deciduous forests, and tropical semi-evergreen forests. Based on Landsat data for 1986, percent coverage by vegetation is: tall grasses 41%, short grasses 11%, open jungle 29%, swamps 4%, rivers and water bodies 8%, and sand 6%.[43]

There is a difference in altitude between the eastern and western areas of the park, with the western side being at a lower altitude. The western reaches of the park are dominated by grasslands. Tall elephant grass is found on higher ground, while short grasses cover the lower grounds surrounding the beels or flood-created ponds. Annual flooding, grazing by herbivores, and controlled burning maintain and fertilize the grasslands and reeds. Common tall grasses are sugarcanes, spear grass, elephant grass, and the common reed. Numerous forbs are present along with the grasses. Amidst the grasses, providing cover and shade are scattered trees—dominant species including kumbhi, Indian gooseberry, the cotton tree (in savanna woodlands), and elephant apple (in inundated grasslands).

Thick evergreen forests, near the Kanchanjhuri, Panbari, and Tamulipathar blocks, contain trees such as Aphanamixis polystachya, Talauma hodgsonii, Dillenia indica, Garcinia tinctoria, Ficus rumphii, Cinnamomum bejolghota, and species of Syzygium. Tropical semi-evergreen forests are present near Baguri, Bimali, and Haldibari. Common trees and shrubs are Albizia procera, Duabanga grandiflora, Lagerstroemia speciosa, Crateva unilocularis, Sterculia urens, Grewia serrulata, Mallotus philippensis, Bridelia retusa, Aphania rubra, Leea indica, and Leea umbraculifera.[44]

There are many different aquatic floras in the lakes and ponds, and along the river shores. The invasive water hyacinth is very common, often choking the water bodies, but it is cleared during destructive floods.[45] Another invasive species, Mimosa invisa, which is toxic to herbivores, was cleared by Kaziranga staff with help from the Wildlife Trust of India in 2005.[46]

Administration

The Wildlife wing of the forest department of the Government of Assam, headquartered at Bokakhat, is responsible for the administration and management of Kaziranga.[22]: p.05 The administrative head of the park is the Director, who is a Chief Conservator of Forests-level officer. A divisional Forest Officer is the administrative chief executive of the park. He is assisted by two officers with the rank of Assistant Conservator of Forests. The park area is divided into five ranges, overseen by Range Forest Officers.[22]: p.11 The five ranges are the Burapahar (HQ: Ghorakati), Western (HQ: Baguri), Central (HQ: Kohora), Eastern (HQ: Agaratoli) and Northern (HQ: Biswanath). Each range is further sub-divided into beats, headed by a forester, and sub-beats, headed by a forest guard.[22]: p.11 The official website of the Park is http://kaziranga.assam.gov.in

The park receives financial aid from the State Government as well as the Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change of Government of India under various Plan and Non-Plan Budgets. Additional funding is received under the Project Elephant from the Central Government. In 1997–1998, a grant of US$ 100,000 was received under the Technical Co-operation for Security Reinforcement scheme from the World Heritage Fund.[24]: p.02 Additional funding is also received from national and international Non-governmental organizations.

Conservation management

Kaziranga National Park has been granted maximum protection under the Indian law for wildlife conservation. Various laws, which range in dates from the Assam Forest Regulation of 1891 and the Biodiversity Conservation Act of 2002 have been enacted for protection of wildlife in the park.[24]: p.01 Poaching activities, particularly of the rhinoceroses for its horn, has been a major concern for the authorities. Between 1980 and 2005, 567 rhinoceroses were hunted by poachers.[22]: p.10 Following a decreasing trend for the past few years, 18 Indian rhinoceroses were killed by poachers in 2007.[47] Reports have suggested that there are links between these poaching activities and funding of terrorist organizations.[48][49] But these could not be substantiated in later years. Preventive measures such as construction of anti-poaching camps and maintenance of existing ones, patrolling, intelligence gathering, and control over the use of firearms around the park have reduced the number of casualties.[50][51] Since 2013, the park used cameras on drones which are monitored by security guards to protect the rhino from armed poachers.[52]

Perennial flooding and heavy rains have resulted in the death of wild animals and damage to the conservation infrastructures.[21] To escape the water-logged areas, many animals migrate to elevated regions outside the park boundaries where they are susceptible to hunting, hit by speeding vehicles, or subject to reprisals by villagers for damaging their crops. To mitigate the losses, the authorities have increased patrols, purchased additional speedboats for patrol, and created artificial highlands for shelter. Several corridors have been set up for the safe passage of animals across National Highway–37 which skirts around the southern boundary of the park.[53] To prevent the spread of diseases and to maintain the genetic distinctness of the wild species, systematic steps such as immunization of livestock in surrounding villages and fencing of sensitive areas of the park, which are susceptible to encroachment by local cattle, are undertaken periodically.

Water pollution due to run-off from pesticides from tea gardens, and run-off from a petroleum refinery at Numaligarh, pose a hazard to the ecology of the region.[22]: p.24 Invasive species such as Mimosa and wild rose have posed a threat to the native plants in the region. To control the growth and irradiation of invasive species, research on biological methods for controlling weeds, manual uprooting and weeding before seed settling are carried out at regular intervals. Grassland management techniques, such as controlled burning, are effected annually to avoid forest fires.[19]

Visitor activities

Observing the wildlife, including birding, is the main visitor activity in and around the park. Guided tours by elephant or Jeep are available. Hiking is prohibited in the park to avoid potential human-animal conflicts. Observation towers are situated at Sohola, Mihimukh, Kathpara, Foliamari, and Harmoti for wildlife viewing. The Lower Himalayan peaks frame the park's landscape of trees and grass interspersed with numerous ponds. An interpretation centre is being set up at the Bagori range of Kaziranga, to help visitors learn more about the park.[54] The park remains closed for visitors from 1 May to end-October due to monsoon rains. Four tourist lodges at Kohora and three tourist lodges outside the park are maintained by the Department of Environment and Forests, Government of Assam. Private resorts are available outside the park borders.[21]: p.19 Increase in tourist inflow has led to the economic empowerment of the people living at the fringes of the park, by means of tourism related activities, encouraging a recognition of the value of its protection.[18]: pp.16–17 A survey of tourists notes that 80 percent found rhino sightings most enjoyable and that foreign tourists were more likely to support park protection and employment opportunities financially, while local tourists favored support for veterinary services.[55] Recently set up Kaziranga National Orchid and Biodiversity Park established at Durgapur village is a latest attraction to the tourists. It houses more than 500 species of orchids, 132 varieties of sour fruits and leafy vegetables, 12 species of cane, 46 species of bamboo and a large varieties of local fishes.[56]

Transport

Authorised guides of the forest department accompany all travelers inside the park. Mahout-guided elephant rides and Jeep or other 4WD vehicles rides are booked in advance. Starting from the Park Administrative Centre at Kohora, these rides can follow the three motorable trails under the jurisdiction of three ranges—Kohora, Bagori, and Agaratoli. These trails are open for light vehicles from November to end Apr. Visitors are allowed to take their own vehicles when accompanied by guides.

Buses owned by Assam State Transport Corporation and private agencies between Guwahati, Tezpur, and Upper Assam stop at the main gate of Kaziranga on NH 37 at Kohora.[57] The nearest town is Bokakhat, Golaghat situated at 23 km and 65 km away. Major cities near the park are Guwahati, Dimapur and Jorhat . Furkating 75 kilometres (47 mi), which is under the supervision of Northeast Frontier Railway, is the nearest railway station. Jorhat Airport at Rowriah (97 kilometres (60 mi) away), Tezpur Airport at Salonibari (approx 100 kilometres (62 mi) away), Dimapur Airport 172 kilometres (107 mi) and Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport in Guwahati (approximately 217 kilometres (135 mi) away) are the nearby airports.. Transportation is also available from Guwahati to Kaziranga National Park and other places in Assam and Nagaland.

In popular culture

Kaziranga has been the theme of, or has been mentioned in, several books, songs, and documentaries. The park first gained international prominence after Robin Banerjee, a physician-turned-photographer and filmmaker, produced a documentary titled Kaziranga, which was aired on television in Berlin in 1961 and became a runaway success.[58][59][60] American science fiction and fantasy author, L. Sprague de Camp wrote about the park in his poem, "Kaziranga, Assam". It was first published in 1970 in Demons and Dinosaurs, a poetry collection, and was reprinted as Kaziranga in Years in the Making: the Time-Travel Stories of L. Sprague de Camp in 2005.

Kaziranga Trail (Children's Book Trust, 1979), a children's storybook by Arup Dutta about rhinoceros poaching in the national park, won the Shankar's Award.[61] The Assamese singer Bhupen Hazarika refers to Kaziranga in one of his songs.[33] The BBC conservationist and travel writer, Mark Shand, authored a book and the corresponding BBC documentary Queen of the Elephants, based on the life of the first female mahout in recent times—Parbati Barua of Kaziranga. The book went on to win the 1996 Thomas Cook Travel Book Award and the Prix Litteraire d'Amis, providing publicity simultaneously to the profession of mahouts as well as to Kaziranga.[62]

Controversy

In 2017, Kaziranga came under severe criticism after a BBC News documentary revealed a hardliner strategy to conservation, reporting the killing of 20 people a year in the name of rhino conservation.[5] As a consequence of this reporting, BBC News was banned from filming in protected areas in India for 5 years.[6] While several news reports claimed that BBC had apologized for the documentary, the BBC stood by its report, with its Director General, Tony Hall, writing in a letter to Survival International that "the letter “in no way constitutes an apology for our journalism.”"[7] As a response to the report, researchers in India have provided more nuanced understanding of the matter, calling out BBC for the carelessness of its journalism, but also pointing to the problems of conservation in Kaziranga[8] and questioning whether shoot-at-sight has been a useful conservation strategy at all.[9]

Economic valuation

Kaziranga Tiger Reserve estimated its annual flow benefits to be 9.8 billion rupees (0.95 lakh / hectare). Important ecosystem services included habitat and refugia for wildlife (5.73 billion), gene-pool protection (3.49 billion), recreation value (21 million), biological control (150 million) and sequestration of carbon (17 million).[63]

See also

References

Notes

- National Park, Kaziranga. "Kaziranga National Park and Tiger Reserve". Kaziranga National Park. our My India and Peak Adventure Tour. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Bhaumik, Subir (17 April 2007). "Assam rhino poaching 'spirals'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Dutt, Anonna (30 March 2018). "Kaziranga National Park's rhino population rises by 12 in 3 years". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018.

- "Welcome to Kaziranga". Archived from the original on 30 April 2012.

- "Kaziranga: The park that shoots people to protect rhinos". BBC News. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- Pinjarkar, Vijay. "Kaziranga report gets BBC banned for 5 years". The Economic Times. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- International, Survival. "BBC boss stands by Kaziranga killings exposé". www.survivalinternational.org. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Grasslands of Grey: The Kaziranga Model Isn't Perfect – But Not in the Ways You Think". The Wire. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Shoot-at-sight is not unjustified. But that alone can't stop poaching at Kaziranga". The Indian Express. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Kaziranga's centenary celebrations". 18 February 2005. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Bhaumik, Subir (18 February 2005). "Kaziranga's centenary celebrations". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Talukdar, Sushanta (5 January 2005). "Waiting for Curzon's kin to celebrate Kaziranga". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 5 November 2009. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Kaziranga National Park–History and Conservation". Kaziranga National Park Authorities.

- Oberai, C. P., & Bonal, B. S. (2002). Kaziranga, the rhino land. Delhi: B.R. Pub. Corp. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Kaziranga Factsheet (Revised) Archived 18 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO, Retrieved on 2007-02-27

- Deka, Arup Kumar. "ULFA & THE PEACE PROCESS IN ASSAM" (PDF). ipcs.org. p. 1-2. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- Official Support Committee, Kaziranga National Park (2009). "History-Legends". Assam: AMTRON. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Mathur, V.B.; Sinha, P.R.; Mishra, Manoj. "UNESCO EoH Project_South Asia Technical Report No. 7–Kaziranga National Park" (PDF). UNESCO. pp. 15–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "UN Kaziranga Factsheet". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Lahan, P; Sonowal, R. (March 1972). "Kaziranga WildLife Sanctuary, Assam. A brief description and report on the census of large animals". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 70 (2): 245–277.

- : p.21 Section II: Periodic Report on the State of Conservation of Kaziranga National Park, India (PDF) (Report). UNESCO. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- : pp. 20–21 Mathur, V.B.; Sinha, P.R.; Mishra, Manoj. "UNESCO EoH Project_South Asia Technical Report–Kaziranga National Park" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Kaziranga National Park". Archived from the original on 1 May 2006.. WildPhotoToursIndia(Through Archive.org). Retrieved on 2007-02-27

- : p.03 "State of Conservation of the World Heritage Properties in the Asia-Pacific Region –Kaziranga National Park" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Phatarphekar, Pramila N. (14 February 2005). "Horn of Plenty". Outlook India. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

- "Kaziranga climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Kaziranga weather averages - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- "Assam flood: Over 500 animals dead in Kaziranga". 7 July 2012. Archived from the original on 27 September 2012.

- AFP English Multimedia Wire (29 August 2006). "Rare rhinos in India face food shortage". Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- "wildlife in Kaziranga National Park". Kaziranga National Park Authorities. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Hussain, Syed Zakir (10 August 2006). "Kaziranga adds another feather – declared tiger reserve". Indo-Asian News Service. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 'Wild buffalo census in Kaziranga', The Rhino Foundation for Nature in NE India, Newsletter No. 3, June 2001

- Rashid, Parbina (28 August 2005). "Here conservation is a way of life". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Elephant Survey in India" (PDF). Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. 2005. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Kaziranga National Park–Animal Survey". Kaziranga National Park Authorities. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Choudhury, A.U. (2010) The vanishing herds: the wild water buffalo. Gibbon Books, Rhino Foundation, CEPF & COA, Taiwan, Guwahati, India

- "Golden tiger spotted in Assam's Kaziranga National Park | WATCH".

- "Wildlife in Kaziranga National Park". Kaziranga National Park Authorities. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- : pp.07–10 Barua, M.; Sharma, P. (1999). "Birds of Kaziranga National Park, India" (PDF). Forktail. Oriental Bird Club. 15: 47–60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Choudhury, A.U. (2003) Birds of Kaziranga: a check list. Gibbon Books & Rhino Foundation, Guwahati, India

- R Cuthbert; RE Green; S Ranade; S Saravanan; DJ Pain; V Prakash; AA Cunningham (2006). "Rapid population declines of Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus) and red-headed vulture (Sarcogyps calvus) in India". Animal Conservation. 9 (3): 349–354. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2006.00041.x. S2CID 52065487.

- Talukdar, B. (1995). Status of Swamp Deer in Kaziranga National Park. Department of Zoology, Guwahati University, Assam.

- Kushwaha, S.& Unni, M. (1986). Applications of remote sensing techniques in forest-cover-monitoring and habitat evaluation—a case study at Kaziranga National Park, Assam, in, Kamat, D.& Panwar, H.(eds), Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Using Remote Sensing Techniques. Indian Institute of Remote Sensing / Wildlife Institute of India, Dehra Dun. pp. 238–247

- Jain, S.K. and Sastry, A.R.K. (1983). Botany of some tiger habitats in India. Botanical Survey of India, Howrah. p71.

- Davis, Wit. "Indian Flooding Update – Hyacinth, Hyacinth Everywhere and no Water to Drink". International Fund for Animal Welfare. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Silent Stranglers, Eradication of Mimosas in Kaziranga National Park, Assam Archived 4 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine; Vattakkavan et al.; Occasional Report No. 12, Wildlife Trust of India, pp. 12–13. Retrieved on 2007-02-26

- "Another rhino killed in Kaziranga". The Times of India. 6 February 2008. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Poachers kill Indian Rhino". The New York Times. 17 April 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- Roy, Amit (6 May 2006). "Poaching for bin Laden, in Kaziranga". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Kaziranga National Park–Heroes of Kaziranga". Kaziranga National Park Authorities. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Two poachers killed in Kaziranga – Tight security measures, better network yield results at park". The Telegraph. 25 April 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "India use drones to protect rhinos from poachers". 9 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013.

- Bonal, BS & Chowdhury, S (2004), Evaluation of barrier effect of National Highway37 on the wildlife of Kaziranga National Park and suggested strategies and planning for providing passage: A feasibility report to the Ministry of Environment & Forests, Government of India.

- "Information Safari". The Telegraph. 31 March 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Shrivastava, Rahul; Heinen, Joel (2003). "A pilot survey of nature-based tourism at Kaziranga National Park and World Heritage Site, India". American Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 30 December 2005.

- "Kaziranga National Orchid Park". Archived from the original on 27 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "Kaziranga National Park Travel Guide". About.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Personalities of Golaghat district. Retrieved on 2007-03-22 Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Robin Banerjee. Retrieved on 2007-03-22 Archived 21 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Lover of the wild, Uncle Robin no more. The Sentinel (Gauhati) 6 August 2003

- Khorana, Meena. (1991). The Indian Subcontinent in Literature for Children and Young Adults. Greenwood Press

- Bordoloi, Anupam (15 March 2005). "Wild at heart". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ghosh, S., Nandy, S., & Kumar, A. S. Rapid assessment of recent flood episode in Kaziranga National Park, Assam using remotely sensed satellite data. Current Science, 111(9), 1450–1451.

Further information

- Barthakur, Ranjit; Sahgal, Bittu (2005). The Kaziranga Inheritance. Mumbai: Sanctuary Asia.

- Sandesh, Kadur; Thengummoottil, George (2014). Kaziranga National Park. ASSAM: UNESCO.

- Choudhury, Anwaruddin (2000). The Birds of Assam. Guwahati: Gibbon Books and World Wide Fund for Nature.

- Choudhury, Anwaruddin (2003). Birds of Kaziranga National Park: A checklist. Guwahati: Gibbon Books and The Rhino Foundation for Nature in NE India.

- Choudhury, Anwaruddin (2004). Kaziranga Wildlife in Assam. India: Rupa & Co.

- Choudhury, Anwaruddin (2010). The vanishing herds : the wild water buffalo. Guwahati, India: Gibbon Books, Rhino Foundation, CEPF & COA, Taiwan.

- Dutta, Arup Kumar (1991). Unicornis: The Great Indian One Horned Rhinoceros. New Delhi: Konark Publication.

- Gee, E.P. (1964). The Wild Life of India. London: Collins.

- Jaws of Death—a 2005 documentary by Gautam Saikia about Kaziranga animals being hit by vehicular traffic while crossing National Highway 37, winner of the Vatavaran Award.

- Oberai, C.P.; B.S. Bonal (2002). Kaziranga: The Rhino Land. New Delhi: B.R. Publishing.

- Shrivastava, Rahul; Heinen, Joel (2007). "A microsite analysis of resource use around Kaziranga National Park, India: Implications for conservation and development planning". The Journal of Environment & Development. 16 (2): 207–226. doi:10.1177/1070496507301064. S2CID 54535379.

- Shrivastava, Rahul; Heinen, Joel (2005). "Migration and Home Gardens in the Brahmaputra Valley, Assam, India". Journal of Ecological Anthropology. 9: 20–34. doi:10.5038/2162-4593.9.1.2.

External links

- Official website of Kaziranga

- "Kaziranga Centenary 1905–2005". Archived from the original on 14 February 2008.

- "World Conservation Monitoring Centre". Archived from the original on 22 March 2007.

- Department of Environment and Forests (Government of Assam)–Kaziranga

- Chaity- A legend of Human-Animal bondage by Abhishek Chakraborty

- Best things to do in Kaziranga National Park

- Rhino census in India's Kaziranga park counts 12 more

.jpg.webp)