Jaan Tõnisson

Jaan Tõnisson[lower-alpha 1] (22 December [O.S. 10 December] 1868, – 1941?) was an Estonian statesman, serving as the Prime Minister of Estonia twice during 1919 to 1920, as State Elder (head of state and government) from 1927 to 1928 and in 1933, and as Foreign Minister of Estonia from 1931 to 1932.

Jaan Tõnisson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd and 4th Prime Minister of Estonia | |

| In office 18 November 1919 – 28 July 1920 | |

| Preceded by | Otto August Strandman |

| Succeeded by | Ado Birk |

| In office 30 July 1920 – 26 October 1920 | |

| Preceded by | Ado Birk |

| Succeeded by | Ants Piip |

| 8th and 15th State Elder of Estonia | |

| In office 9 December 1927 – 4 December 1928 | |

| Preceded by | Jaan Teemant |

| Succeeded by | August Rei |

| In office 18 May 1933 – 21 October 1933 | |

| Preceded by | Konstantin Päts |

| Succeeded by | Konstantin Päts |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 December 1868 Viiratsi Parish, Governorate of Livonia, Russian Empire |

| Died | presumably 1941 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | Estonian |

| Political party | Progressive People's Party (1905–1917) Democratic Party (1917–1919) Estonian People's Party (1919–1932) National Centre Party (1932–1935) later none |

| Alma mater | University of Tartu |

| Profession | lawyer, newspaper editor, politician |

After the Soviet invasion and occupation Estonia in June 1940, Tõnisson was arrested by the Stalinist terror regime and, like most senior Estonian politicians at the time, was either executed or died in Soviet captivity soon afterwards. Tõnisson was still alive in June 1941, when he is known to have been imprisoned, and interrogated, in Tallinn. The exact date and location of his death and place of burial remain unknown. According to circumstantial evidence, Tõnisson was most probably executed by the Soviet NKVD in the beginning of July 1941.

Early life

Tõnisson was born on 22 December [O.S. 10 December] 1868 near Tänassilma, Viiratsi Parish, Viljandi County, then part of the Governorate of Livonia of the Russian Empire. He grew up during the Estonian national awakening, being inspired by nationalist ideas already in his childhood.[1]

Tõnisson studied in the parish school and later also in high school of Viljandi. He went on to study at the Faculty of Law of the University of Tartu, graduating in 1892 with a degree in law (candidatus juris). While at university, he joined the young fraternal Estonian Students' Society, a group which played an important role in the national movement in the late 19th and early 20th century. Tõnisson became the chairman of the society, acquainting him with Villem Reimann, leader of the national movement of that time.[1]

Career

National movement

Russification policy had closed several Estonian organizations and prominent students, including Jaan Tõnisson, started speaking up, finding support among ethnic Estonians.[1]

In 1893, Tõnisson became the editor of the largest by circulation Estonian daily Postimees. With the help of Tõnisson, the "Tartu Renaissance", a period when Estonians sought to weaken the Russification policy. In 1896, Tõnisson, along with several of his closest associates, bought the newspaper Postimees turning it into the tribune of the national movement for the decades to follow.[2] Tõnisson supported nationalism, that would stand on strong moral grounds and wouldn't seek to conquer other nations. In his mind, a nation would have to grow strong in spirit.[1]

Tõnisson also fought for the development of the Estonian economy, paying special attention to the joint activities, such as the establishing of the first agricultural co-operatives in Estonia, also the Estonian Loan and Savings Society was founded after his initiative.[3]

In 1901, Konstantin Päts founded the second Estonian daily newspaper, starting a political rivalry not only between Postimees and the new Teataja, but also between Jaan Tõnisson and Konstantin Päts themselves. Tõnisson was to lead the "moralist" and Päts the "economic" fraction of the national movement. Both tried to become leading national figures, Tõnisson was ideological and nationalist, Päts emphasized the importance of economic activity.[4]

Early political career

While Tõnisson did not approve of Estonians participating in the Revolution of 1905, it did not prevent him from passionately protesting against the punishment actions in Estonia, organized by the imperial powers. Lacking support for Estonians participating in the revolution, Tõnisson got into conflicts with more radical Estonian politicians. This however saved him from having to go to exile, as did Konstantin Päts and Otto Strandman.[1]

Following the revolution, Emperor Nicholas II was forced to give citizens certain political freedoms. Tõnisson used the October Manifesto to widen the rights of Estonians, establishing the first Estonian political party – Estonian National Progress Party (Eesti Rahvuslik Eduerakond – ERE; or Eesti Rahvameelne Eduerakond – Estonian Progressive People's Party) together with Villem Reiman.[2] The party supported improving the nationalist and liberal ideas and constitutional rights. The platform was similar to the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) of Russia, with minor differences in agricultural and nationality issues. It was seen as having moderate policies for not supporting the revolution, but still wanted ethnic Estonians to have equal rights with Russians and Baltic Germans and wanted Russia to be a constitutional monarchy.[5] Unlike more radical political groups, the National Progress Party remained legal also after the Revolution had been forced down.[6]

In December 1905, Tõnisson organised the gathering of Estonian representatives in Tartu. Soon after its first meeting, many representatives supported Jaan Teemant, who was a keen supporter of the revolution, to be the chairman of the meeting instead of the more moderate Tõnisson. Teemant won the election overwhelmingly, but Tõnisson refused to leave. Eventually, Tõnisson and his moderate supporters left the gathering, while the remaining representatives turned the meeting into a discussion about how to take revolutionary power, much to the dismay of even Jaan Teemant.[5]

In 1906, the National Progress Party saw great support and Tõnisson was among the four Estonian politicians to be elected to the First State Duma in 1906, where he joined the Autonomist-Federalist group. Tõnisson was elected to the board of this group and he organized a separate Baltic fraction for the group.[7] He also joined the protest movement against the actions of the Russian government, trying to protect the new rights that the Emperor was trying to take back.[1]

On 23 June 1906, Tõnisson and 177 other members of the State Duma signed Vyborg Appeal, calling for disobedience, in protest against the dissolution of the State Duma. Tõnisson was removed from the Postimees board (he resumed shortly afterwards) and in December 1907, he was put on trial. Tõnisson was sentenced to three months in Tartu prison.[8] Prison did not inhibit Tõnisson's political activity. In the years following the revolution he concentrated on developing the Estonian school system, founding school societies all over the country and opening several Estonian-language high schools. The co-operation and agriculture policies, that Tõnisson had established, developed quickly, creating an Estonian civil society and influencing the general growth of wealth in Estonia.[1] In 1915, Jaan Tõnisson and Jaan Raamot initiated the creation of Northern Baltic Committee for the protection of war refugees. Tõnisson serves as chairman of the committee until 1917, hoping to get closer to administrative power.[7]

Autonomy

Following the February Revolution, Estonians quickly reacted and gained the rights to autonomy and to form a national army from the Russian Provisional Government. In March 1917, Tõnisson met with Prime Minister of Russia Georgy Lvov, who however couldn't promise autonomy and said that the Russian Provincial Assembly.[9] In the debates about the autonomy, Tõnisson supported the current division of Estonia with two governorates, only with autonomy for each. Konstantin Päts's idea of a single Autonomous Governorate of Estonia went through and Tõnisson, among some other Estonian politicians, was chosen to compose the draft of self-government reform.[10] Tõnisson was often among the few politicians, who contacted directly with the Russian Provisional Government in these questions.[11] Eventually, the Autonomous Governorate of Estonia was created and Tõnisson was elected to the Estonian Provincial Assembly (Maapäev) in 1917. His party, renamed to Estonian Democratic Party (Eesti Demokraatlik Erakond – EDE), achieved 7 of the 55 seats.

At first, Tõnisson proposed the idea of a Scandinavian superstate, that eventually involved into supporting total secession from Russia.[9] However, in late autumn 1917, Tõnisson was among the first Estonian politicians, who started demanding full independence for Estonia.[1] After the October Revolution, local communists disbanded the Provincial Assembly. On 28 November 1917, most of its members met in Toompea Castle and declared the assembly to be the highest legitimate power in Estonia. In a speech in the parliament, Tõnisson emphasized the situation of anarchy in Russia and supported the declaration, that eventually turned into a successful coup d'etat.[12]

Subsequently, Tõnisson was arrested by Bolshevik forces on 4 December 1917 for organizing a pro-Provincial Assembly meeting in Tartu. He was forced out of the country on 8 December. The Council of Elders of the assembly came together underground and decided to make him an Estonian delegate to Stockholm to find support for Estonian independence, or at least for its autonomy.[12] Tõnisson and other members of the Russian Provincial Assembly were named Estonian delegates abroad and Tõnisson became the leader of Estonian Foreign Delegations, a position that would still be his when Estonia declared its independence on 24 February 1918.[1] The delegations were eventually turned into embassies and in Stockholm, Tõnisson met with German and French ambassadors to find support for Estonian independence, but was later sent to Copenhagen, though several Estonian delegates eventually gathered in Stockholm.[13] On 16 March 1918, Swedish Minister of Foreign Affairs agreed to meet the delegates, but didn't grant any support.[14] After the German Occupation of Estonia had ended, Tõnisson returned to Estonia on 16 November 1918.[15]

Independence

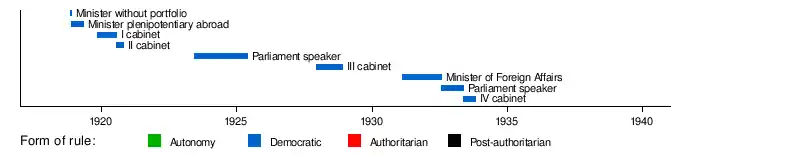

From 12 November 1918, Tõnisson served as Minister without portfolio[16] and from 27 November 1918 to 9 May 1919 as Minister plenipotentiary abroad of the Estonian Provisional Government, led by Konstantin Päts.[17] Tõnisson's offices sent him abroad again, this time to Finland to seek weaponry and loans in the coming War of Independence. He was also part of the Estonian delegation at the Paris Peace Conference.

For the elections to the Estonian Constituent Assembly, Tõnisson had yet again transformed his party, this time to the Estonian People's Party.[6] In the elections of the Constituent Assembly in spring 1919, the centre-right (conservative-liberal) People's Party took 25 of the 120 seats, fewer than the Estonian Social Democratic Workers' Party (ESDTP) and the Labour Party. The shape of the new republic was to be determined by parties of the left and parties of the centre, including Tõnisson's People's Party.

On 18 November 1919, Tõnisson became the Prime Minister of Estonia. Already on the next day, the government decided, that Estonia would start peace negotiations with Russia and on 2 February 1920, the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed, ending the War of Independence. With the treaty, Estonia and Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic became the first countries to recognize each other's independence. Several countries at Russia's border and also in the West reacted negatively on Estonia's decision to sign peace with Soviet Russia.[18] In December 1920, relations with Latvia deteriorated, when Estonia forced Latvian administration out of the border town of Valga (Valka). Through British mediation, the conflict was resolved and Valga was divided between the two countries.[19]

The coalition consisted of the three major parties in the parliament: Tõnisson's People's Party with the social democratic ESDTP and the centre-left Labour Party. On 1 July 1920, ESDTP left the coalition because of ideological differences and the entire cabinet fell on 28 July 1920, after Tõnisson failed to find a new coalition partner.[20]

A new head of government was hard to find. Members of the Labour Party failed in the attempt to find support and another member of the People's Party, Ado Birk was chosen to head the new cabinet. He however, also didn't get the support of the Constituent Assembly and his cabinet was in office only nominally for three days. From 30 July 1920 to 26 October 1920, Jaan Tõnisson headed his second cabinet as Prime Minister in the one-party coalition.[21]

The Estonian People's Party quickly lost its popularity and became one of the smallest parties in the parliament, getting only 10 in the 1920 elections, 8 in the 1923 elections and the 1926 elections and 9 of the 101 seats in the 1929 elections. Tõnisson himself however remained popular and despite the few seats in the Riigikogu, the Estonian People's Party was a coalition member in nine of the twelve cabinets between 1920 and 1932. A prominent member of the People's Party, Jüri Jaakson, was even State Elder of the grand coalition cabinet after the Communist coup attempt from 1924 to 1925.[22] From 7 June 1923 to 27 May 1925, Tõnisson served as the President (speaker) of the Riigikogu.[23]

Jaan Tõnisson formed his third cabinet on 9 December 1927, for the first time as State Elder. It was another wide coalition with the Labour Party, Settlers' party and Farmers' Assemblies. The government fell on 4 December 1928.[24]

Tõnisson returned to big politics on 12 February 1931, when he became the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Konstantin Päts's cabinet.[25] During the early 1930s, the political climate in Estonia changed. In October 1931, the Christian People's Party merged into the Estonian People's Party[6] which joined with the Labour Party to form the National Centre Party in early 1932. Three major parties had emerged in the Riigikogu, the left-wing Estonian Socialist Workers' Party, the center-right National Centre Party and the right-wing Union of Settlers and Smallholders. Päts's cabinet resigned, but Tõnisson remained in the same office also in Jaan Teemant's cabinet until it also resigned on 19 July 1932.[26]

The 1932 elections brought the National Centre Party 23 of the 101 seats in the Riigikogu, making it the second biggest party in the parliament. Tõnisson then served again as the President (speaker) of the Riigikogu from 19 July 1932 to 18 May 1933.[23]

Due to economical differences, the National Centre Party had left the governing coalition and Jaan Tõnisson formed his fourth cabinet on 18 May 1933. The refounded Settlers' Party, that had again seceded from the Union of Settlers and Smallholders, was the only coalition partner for the People's Party.[27]

Decisions of Tõnisson's government during the financial crisis in 1932 led to a total decline in his personal popularity, though the policies would help the state out of the crisis. In a referendum in 1933, the voters adopted a new constitution which reduced the powers of the Parliament, and increased those of the President. As a result, the head of state Konstantin Päts was able to consolidate his control of the state after a self coup in 1934. Päts also suspended the activities of both the political parties and the parliament (until the elections in 1938).[1]

With the changing situation in Estonia, Tõnisson became the leader of the democratic opposition. Although his newspaper Postimees had been expropriated in 1933, it did not keep Tõnisson from promoting democratic ideals.[1]

The semi-democratic elections of 1938, Tõnisson was re-elected to the State Assembly (Riigivolikogu), the lower chamber of the Riigikogu, where he continued fighting for the total restoration of democracy in Estonia.[1]

After the Stalinist Soviet Union invaded Estonia in 16 June 1940, Tõnisson reportedly tried to convince President Konstantin Päts about the necessity of armed resistance to the Soviet invaders, at least symbolically, however Päts had by that time already decided to surrender without resistance.[1]

Tõnisson made an attempt to organise the nomination of rival candidates to the communist ones in the July 1940 sham elections of the new "Soviet" puppet parliament in Estonia. The Soviet occupation regime removed all opposition candidates from the ballot.[1]

Membership in the parliament:

- 1917–1919 Estonian Provincial Assembly (Maapäev)

- 1919–1920 Estonian Constituent Assembly

- 1920–1923 I Riigikogu

- 1923–1926 II Riigikogu

- 1926–1929 III Riigikogu

- 1929–1932 IV Riigikogu

- 1932–1934/1937 V Riigikogu

- 1938–1940 VI Riigikogu – Riigivolikogu

Disappearance

Soviet authorities arrested Tõnisson in autumn 1940 and put him on trial. During his trial, Tõnisson neither regretted anything nor gave up any information about other politicians who opposed the Soviets. The exact whereabouts of Tõnisson after the trial and the circumstances of his death remain a mystery. The most credible speculation about his death centres on Tõnisson being shot dead in Tallinn during the first days of July in 1941. His place of burial is unknown.[28]

Tõnisson's moral views and honorable death inspired Estonians for decades to symbolically resist the Soviet regime and to eventually regain independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. A memorial to Tõnisson was erected in Tartu in 1999.[1]

Awards

- 1920 – Cross of Liberty II/III

- 1920 – Cross of Liberty III/I

- 1925 – Cross of Liberty I/III

- 1928 – Order of the Estonian Red Cross I/I

- 1930 – Order of the Cross of the Eagle I

- 1938 – Order of the White Star I

- 1932 – Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion (Czechoslovakia)

- 1939 – Royal Order of the Polar Star (Sweden) Grand Cross

See also

Notes

- Estonian pronunciation: [ˈjɑːn ˈtɤnisːon]

References

- Poliitik ja aatemees Jaan Tõnisson Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: an introduction to the people, lands, and culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 32

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 27

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 55

- Histrodamus – Eesti olulisemad erakonnad

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 60

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 69

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 149

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 150

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 151

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 162

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 166

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 172

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 180

- Vabariigi Valitsus – Ajutine Valitsus 12.11.1918 – 27 November 1918 Archived 15 March 2012 at archive.today

- Vabariigi Valitsus – Ajutine valitsus 27 November 1918 – 09.05.1919 Archived 13 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 210

- XX sajandi kroonika, I osa; Eesti Entsüklopeediakirjastus, Tallinn, 2002; p. 208

- Vabariigi Valitsus – Vabariigi Valitsus 18 November 1919 – 28 July 1920 Archived 27 September 2011 at archive.today

- Vabariigi Valitsus – Vabariigi Valitsus 30 July 1920 – 26 October 1920 Archived 27 September 2011 at archive.today

- Vabariigi Valitsus Vabariigi Valitsus 16 December 1924 – 15 December 1925 Archived 27 September 2011 at archive.today

- "Riigikogu juhatus". Riigikogu.

- Vabariigi Valitsus – Vabariigi Valitsus 09.12.1927 – 04.12.1928 Archived 27 September 2011 at archive.today

- Vabariigi Valitsus Vabariigi Valitsus 12.02.1931 – 19 February 1932 Archived 27 September 2011 at archive.today

- Vabariigi Valitsus – Vabariigi Valitsus 19 February 1932 – 19 July 1932 Archived 27 September 2011 at archive.today

- Vabariigi Valitsus – Vabariigi Valitsus 18 May 1933 – 21 October 1933 Archived 23 March 2012 at archive.today

- Miljan, Toivo (21 May 2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780810875135.

External links

- Jaan Tõnisson Institute

- Jaan Tõnisson at the President of the Republic of Estonia website (in Estonian)