Indochine (film)

Indochine (French pronunciation: [ɛ̃dɔʃin]) is a 1992 French period drama film set in colonial French Indochina during the 1930s to 1950s. It is the story of Éliane Devries, a French plantation owner, and of her adopted Vietnamese daughter, Camille, set against the backdrop of the rising Vietnamese nationalist movement. The screenplay was written by novelist Érik Orsenna, screenwriters Louis Gardel and Catherine Cohen, and director Régis Wargnier. The film stars Catherine Deneuve, Vincent Pérez, Linh Dan Pham, Jean Yanne and Dominique Blanc. The film won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film at the 65th Academy Awards, and Deneuve was nominated for Best Actress.[2]

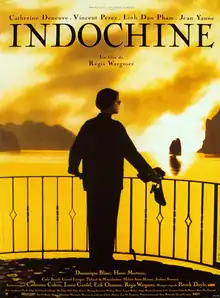

| Indochine | |

|---|---|

French theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Régis Wargnier |

| Written by | Érik Orsenna Louis Gardel Catherine Cohen Régis Wargnier |

| Produced by | Eric Heumann Jean Labadie |

| Starring | Catherine Deneuve Vincent Pérez Linh Dan Pham Jean Yanne |

| Cinematography | François Catonné |

| Edited by | Agnès Schwab Geneviève Winding |

| Music by | Patrick Doyle |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | BAC Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 159 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Languages | French Vietnamese |

| Box office | $29.6 million[1] |

Plot

The story is narrated by Éliane Devries, a woman born to French parents in colonial Indochina, and is told through flashbacks. In 1930, Éliane runs her and her widowed father's large rubber plantation with many indentured laborers, whom she casually refers to as her coolies, and divides her days between her homes at the plantation and outside Saigon. She is also the adoptive mother of Camille, whose birth parents were friends of Éliane's and members of the Nguyễn dynasty. Guy Asselin, the head of the French security services in Indochina, courts Éliane, but she rejects him and raises Camille alone giving her the education of a privileged European through her teens.

Éliane meets a young French Navy lieutenant, Jean-Baptiste Le Guen, when they bid on the same painting at an auction. She is flustered when he challenges her publicly and surprised when he turns up at her plantation days later, searching for a boy whose sampan he set ablaze on suspicion of opium smuggling. Éliane and Jean-Baptiste begin a torrid affair.

Camille meets Jean-Baptiste by chance one day when he rescues her from a terrorist attack. Believing him to have saved her life, Camille falls in love with Jean-Baptiste at first sight, while Jean-Baptiste has no inkling of Camille's relation to Éliane. When Éliane learns of Camille's love for Jean-Baptiste, she uses her connections with high-ranking Navy officials to get Jean-Baptiste transferred to Haiphong. Jean-Baptiste angrily confronts Éliane about his transfer during a Christmas party at her home, resulting in a heated argument where he slaps her in front of his fellow officers. For his transgression, Jean-Baptiste is sent to the notorious Dragon Islet (Hòn Rồng), a remote French military base in northern Indochina.

Éliane allows Camille to become engaged to Thanh, a pro-Communist Vietnamese boy expelled as a student from France because of his support for the 1930 Yên Bái mutiny. A sympathetic Thanh allows Camille to search for Jean-Baptiste up north. Camille travels on foot and eventually makes it to Dragon Islet, where she and a Vietnamese family she travels with are imprisoned alongside other laborers. When Camille comes across the sight of her traveling companions brutally tortured and murdered by French officers, she attacks a French officer and shoots him in the struggle. Jean-Baptiste defies his superiors to protect Camille in the ensuing firefight, and the two set sail and escape Dragon Islet as outlaws.

After spending several days adrift in the Gulf of Tonkin, Camille and Jean-Baptiste reach land and are taken in by a Communist theater troupe, who offers the couple refuge in a secluded valley. After several months, Camille has become pregnant with Jean-Baptiste's child, but they are told they must vacate the valley out of safety. Thanh, now a high-ranking Communist operative, arranges for the theater troupe to smuggle the lovers into China.

Guy attempts to use operatives to quell the growing insurrections by laborers and to locate Camille and Jean-Baptiste, without success. Camille and Jean-Baptiste's story becomes a celebrated legend in tuồng performances by Vietnamese actors, earning Camille the popular nickname "the Red Princess". When the couple nears the Chinese border, Jean-Baptiste takes his and Camille's newborn son to baptize him in a river while she's asleep. After christening the baby Étienne, he is ambushed and apprehended by several French soldiers. A distraught Camille evades capture and escapes with the theater troupe, while French authorities remand Jean-Baptiste to a Saigon jail and hand Étienne over to Éliane.

After some days in prison, Jean-Baptiste agrees to talk if he can first see his son. The Navy, which has authority over the case and refuses to subject Jean-Baptiste to interrogation by the police, plans to court-martial Jean-Baptiste in Brest, France to avoid the public outcry that would likely arise from a trial in Indochina. Jean-Baptiste is allowed a 24-hour visitation with Étienne before being taken to France. He goes to see Éliane, who lets him stay with Étienne at her Saigon residence for the night.

The next day, Éliane finds Jean-Baptiste dead in his bed with a gunshot to his temple, a gun in hand, and an unharmed Étienne. Outraged, Éliane tells Guy she suspects the police murdered him, but Guy's girlfriend tells Éliane that the Communists may have killed Jean-Baptiste to silence him. With no evidence sought for either suspicion, Jean-Baptiste's death is ruled a suicide. Camille is captured and sent to Poulo-Condor – a high security prison where visitors are not permitted and not even Éliane or Guy can help free her. After five years, the Popular Front comes to power and releases all political prisoners including Camille. Éliane reunites with Camille, but she declines to return to her mother and son, choosing instead to join the Communists and fight for Vietnam's independence. Camille reasons she does not wish for her son to know the horrors she has witnessed, and tells her mother that French colonialism is drawing to an end. Taking Étienne with her, Éliane sells her plantation and leaves Indochina.

In 1954, Éliane finishes telling her story to a grown Étienne. They have both come to Switzerland, where Camille is a Vietnamese Communist Party delegate to the Geneva Conference. Étienne goes to the negotiators' hotel intending to find his birth mother, but it is so crowded with people that he is not sure how Camille can find or recognize him. He tells Éliane he sees her as his mother.

As the film concludes, an epilogue notes the next day, French Indochina becomes independent from France and Vietnam is partitioned into North and South Vietnam.

Cast

- Catherine Deneuve as Éliane Devries

- Vincent Pérez as Jean-Baptiste

- Linh Dan Pham as Camille

- Jean Yanne as Guy

- Dominique Blanc as Yvette

- Henri Marteau as Émile

- Kieu Chinh as Mme. Minh Tam

- Eric Nguyen as Thanh

- Jean-Baptiste Huynh as Étienne

- Carlo Brandt as Castellani

- Hubert Saint-Macary as Raymond

- Andrzej Seweryn as Hébrard

- Thibault de Montalembert as Charles-Henri

- Như Quỳnh as Sao

Production

The film was shot mainly in Imperial City, Hue, Ha Long (Ha Long Bay) and Ninh Binh (Phát Diệm Cathedral) in Vietnam.[3] Butterworth in Malaysia was used as a substitute for Saigon and Éliane Devries' "Lang-Sai" plantation house was actually Crag Hotel in Penang, Malaysia.[4][5] Some parts were filmed in Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion, in George Town, Penang, Malaysia.[6] Principal photography began on April 8, 1991, and concluded on August 22, 1991.

Release

Box office

The film received a total of 3,198,663 cinema-goers in France, making it the 6th most attended film of the year.[7] The film also grossed $5,603,158 in North America.[8]

Critical reception

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Indochine holds an approval rating of 75%, based on 20 reviews, and an average rating of 6.4/10.[9]

Critics' reviews praised the film's photography and scenery, while citing issues with the plot and character development. Roger Ebert wrote the film "intends to be the French 'Gone with the Wind,' a story of romance and separation, told against the backdrop of a ruinous war". He continued "'Indochine' is an ambitious, gorgeous missed opportunity – too slow, too long, too composed. It is not a successful film, and yet there is so much good in it that perhaps it's worth seeing anyway…The beauty, the photography, the impact of the scenes shot on location in Vietnam, are all striking.“[10]

Rita Kempley of The Washington Post found the transformation of Camille from a naive, pampered innocent to Communist revolutionary to be a compelling plot line, but noted, "The trouble is we never see the fragile teenager undergo this surprising metamorphosis. Director Regis Wargnier seems far more interested in what the white folks are doing back on the plantation". She commented further, "Wargnier, who learned his craft at the elbow of Claude Chabrol, does expose the geographic splendors of Southeast Asia as well as the common sense of its people, whose sly observations lend 'Indochine' both energy and levity".[11]

Of the film's metaphorical mother-daughter relationship between Éliane and her adopted Vietnamese daughter Camille, Nick Davis said “Indochine's allegorical intentions actually play much better than the specific dramas enacted among its characters", adding "While Eliane-as-Establishment, Jean-Baptiste-as-Rebellious-Lower-Class-Youth, and Camille-as-Uneasy Cultural Mixture seem to follow the historical pattern of France's relationship with Indochina, their interactions only make sense to the extent they are interpreted as solely symbolic figures".[12]

Accolades

- The film was selected for screening as part of the Cannes Classics section at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival.[18]

See also

References

- "Indochine (1992) – JPBox-Office".

- "The 65th Academy Awards (1993) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- Ng, Josee (1 October 2021). "Indochine (1992): A Historical Movie About Vietnam That Won An Oscar". TheSmartLocal Vietnam. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "Saigon on the Silver Screen". saigoneer.com.

- "Borneo Expat Writer". 19 November 2009.

- "Cheong Fatt Tze Mansion". Architectural Digest. 31 July 2003.

- "Indochine (1992) – JPBox-Office".

- "Indochine". Box Office Mojo.

- "Indochine". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- Ebert, Roger (5 February 1993). "Indochine movie review". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Kempley, Rita (5 February 1993). "Indochine". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Davis, Nick. "Indochine". Nick’s Flick Picks. Archived from the original on 28 February 2001. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1994". BAFTA. 1994. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "The 1993 Caesars Ceremony". César Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Indochine – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "1992 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "1992 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Cannes Classics 2016". Cannes Film Festival. 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2016.