History of the University of Arkansas

The History of the University of Arkansas began with its establishment in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in 1871 under the Morrill Act, as the Arkansas Industrial College. Over the period of its nearly 140-year history, the school has grown from two small buildings on a hilltop to a university with diverse colleges and prominent graduate programs. Its presidents have included Civil War general Daniel Harvey Hill, John C. Futrall, and J. William Fulbright.

Establishment of the University

Prior to the establishment of the University of Arkansas, higher education existed sporadically throughout the state of Arkansas in the form of small academies and institutions, such as Cane Hill College not far from Fayetteville, and St. John's College in Little Rock.[1] In addition, Fayetteville was also home to Arkansas College, which enjoyed a high reputation statewide and regionally until the destruction of the school's buildings in 1862 by fire.[2] However, by the outbreak of the Civil War, there were no state supported institutions, despite Antebellum attempts by various Arkansas governors to use the proceeds from federal lands bequeathed to Arkansas upon achieving statehood to establish an endowment for their creation. Instead, these funds were siphoned off by the legislature for support of other state programs.[3] Incidentally, the same year that saw the burning down of Arkansas College also saw the introduction of legislation in the United States Congress that eventually resulted in the establishment of the University of Arkansas.

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act, which offered to states federal land to sell with the proceedings going towards the establishment of state educational institutions. It was not until Reconstruction that the Arkansas legislature was able to take advantage of the act. The legislature had already shown its desire to establish an institution with Article 9, Section 3, of the Arkansas Constitution of 1868, which stated:

The General Assembly shall establish and maintain a State University, with departments for instruction in teaching, in agriculture and the natural sciences, as soon as the public school fund will permit.[4]

Finally, in 1871, after one aborted attempt to pass a statute to mandate the establishment of an institution, the legislature passed, "An Act for the Location, Organization, and Maintenance of the Arkansas Industrial University, with a Normal Department Therein." This act called upon the legislature to accept the Morrill Act, establish a board of trustees, and established a process by which "any county, city, or incorporated town," could compete to be the location of the university by means of bonds, taxes, and donated sums.[5] However, by the rules of the Morrill Act, the state had until February 12, 1872, to have the university founded and operating to qualify, leaving less than a year to accomplish the deed.[6]

There were three principal competitors to be the host of the new state university, Pulaski County (Little Rock), Independence County (Batesville), and Washington County (Fayetteville and Prairie Grove). Of the three, however, only the Fayetteville-Prairie Grove and Batesville supporters won requisite local elections to legitimize their bids to the legislature created board of trustees. The board of trustees was composed of eleven members, the state superintendent of public instruction, ex-officio president, and ten elective members approved by vote of a joint meeting of the Arkansas legislature with each selected from one of the ten judicial districts.[7] Two men, Lafayette Gregg and David Walker, were among the primary pushers in Washington County to secure the successful passage of the bid via election and later played instrumental roles in the university's history. At this point, the board of trustees then traveled to both towns to judge the locations personally before selecting the winning bid.[8]

The board of trustees visited Batesville on September 24, 1871, and arrived in Fayetteville after a journey that involved the usage of trains, stagecoaches and steam boats by October. By the 11th of same month, the board of trustees put to a vote the two choices of Fayetteville and Batesville for the location of the new university. In a mixed vote, Fayetteville was selected, with the majority of the board in favor of Washington County as the location of the University of Arkansas.[9]

Construction

Upon the selection of Fayetteville as the location for the state university, the board established two committees; one to supervise the procurement of land and construction of facilities, the other to organize the actual selection of instructors, establish departments, and to equip the university for operation. The date of their establishment was approximately four months prior to the deadline of February 12, 1872, after which the state would lose the benefits of the land grant act if the two committees could not have the university up and running by that time.[10]

The homestead of William McIlroy, a local farmer and merchant, had been selected as a location for the university and purchased at cost of $12,000 by the Fayetteville lobbying committee prior to the final decision of the board.[11] At the time, the grounds consisted of a total of 160 acres (0.65 km2), just over a third of it cultivated, a six-room residence, several outbuildings, and an orchard spread over four acres. By January 1, 1872, the committee had arranged for the completion of a two-story frame building, no more than twenty-four by forty feet and with enough room to hold around 120 students. The total expense of the building was only $975, a fraction of the planned cost a permanent main building limited to $120,000. Six months later, a second similar building was erected for twice as much as the first to satisfy expected demands of the first matriculating class.[12]

The construction of the iconic Old Main building did not begin until 1874. Earlier, the board of trustees had placed newspaper advertisements inviting architectural plans in line with a building costing between $85,000 and $120,000. From this search, the board had initially adopted plans drawn up by the Helena firm of McKay and Hemle. This decision did not remain in plan for long, due to the lobbying by individuals who had visited the University of Illinois previously by the selection of the board to investigate similar land grant universities. The lobbyists had returned with flattering drawings and descriptions of school's university hall and had quickly won over the board. The design by McKay and Hemle was dropped, and the board purchased a copy of the Illinois building plans, designed by Chicago architect John M. Van Osdel for $1,000.[13]

On July 4, 1873, the board of trustees opened up bidding for the construction of the hall, which was eventually won by the local Fayetteville firm of Mayes and Oliver at a bid of $123,855. Incidentally, John McKay of McKay and Hemle, was given the job of supervising architect by friends on the board, a job he held for one year until dismissed by a new board. Alexander Hendry was selected as his replacement by Lafayette Gregg, who had played an instrumental role in bringing the university to Fayetteville, and later, closely oversaw the construction of Old Main. Much of the materials of the building were of local origin, with sandstone quarried near to the university, while the bricks (over 2.5 million of them) were fired not far from the present student union.[14] Construction was declared complete and the hall opened on June 17, 1885. Despite the declaration, the upper two floors and the basement were left unfinished due to the belief they would be finished later when the student population had grown larger. The final cost of the building was more than $134,000.[15]

The early years

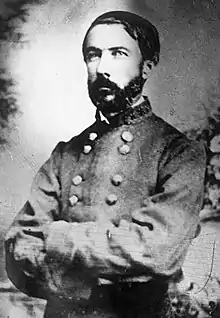

The first graduation ceremony held was in the spring of 1876, and consisted of a class consisting of students entirely from Fayetteville and numbering eight.[16] Over the next fifteen years, approximately 5,000 students matriculated through the university.[17] From the opening of the university until 1877, the school was watched over first by an acting president, Noah P. Gates, then the first permanent president, General Albert Webb Bishop, and again by Gates, upon Bishop's resignation[18] as the Reconstruction period ended in Arkansas. Bishop, a Union general, was replaced by Daniel H. Hill, a Confederate general, in June 1877 after General Joseph E. Johnston turned down the offer of the presidency.[19] Hill brought an emphasis on classical and mathematical education, and downplayed the agricultural and technological elements for which the university had originally been established. Furthermore, Hill placed great importance on discipline, willingly expelling students for non-academic violations.[20]

By June 1884, Hill, tired of in fighting with the faculty, resigned after seven years and was replaced by another Confederate veteran, Colonel George. M. Edgar.[21] Problems concerning the direction of the school led Edgar to resign only three years later, to be replaced by Colonel Edward H. Murfee. Under Murfee, and his predecessor ten years later, Albert E. Menke, the school was pushed by Little Rock to adopt and promote its agricultural mission.[22] For all that the legislator in Little Rock pushed for the school to adhere to its founding principle, a lack of interest by both students and faculty resulted in general failure.[23] President John Lee Buchanan, former professor of Latin at Vanderbilt University, saw the university into the 20th century, as well the change of the school's official name of Arkansas Industrial University to University of Arkansas in 1899.[24]

During this time period, the student publications appeared, such as The Cardinal (later replaced by The Razorback), as well as the Arkansas Traveler, the school's newspaper. Hill Hall, later demolished to make way for David W. Mullins Library, was constructed in 1901 as a boys' dormitory.[25] Shortly thereafter, Buchanan retired to be replaced by Henry S. Hartzog, who was then followed by John N. Tillman. It was during Hartzog's tenure that Carnall Hall, a girls' dormitory, was built, and remains standing to this day.[26] Tillman had been the selection of Governor Jeff Davis, and a blatantly political one at that. Such was the outrage of his predecessor, Hartzog, that the former president used his pulpit at the 1905 graduation, to rail against the decision as his last speech in an official capacity.[27] Under Tillman, the tradition of Senior Walk was begun in 1905, the school officially changed its mascot from the cardinal to the razorback, as well was held the competition that selected the school's alma mater (won by Brodie Payne for a reward of $50). Tillman's presidency came to a screeching stop in 1912 due to student protests over a scandal concerning school finances, which resulted in the expulsion of 36 students, that in turn led to general strike by the entire student body that lasted four days. The student dislike of their president, joined with the support of the citizens of Fayetteville, was enough to lead the board of trustees to request Tillman's resignation. Tillman's popularity suffered little, as two years later, he was elected to the first of five terms as a United States Congressman.[28]

Presidency of John C. Futrall

After two tenuous years of temporary presidents and a nationwide search for a permanent replacement to Tillman, the board of directors finally selected John Clinton Futrall as the university president. Futrall was not a candidate from afar, but had been a professor of Latin and Greek since 1895, and was the first head coach of the school's football team. Inherited from Tillman's administration was a dire financial crisis, severe enough that the school had to borrow money to pay for student labor. Futrall quickly sought to correct the situation by lowering salaries, decreasing services, and firings. His goal of fiscal solidity for the university was joined by Governor Charles H. Brough, who pushed through legislation guaranteeing the school a percentage of the state property tax.[29]

Futrall's administration remains to the present the longest of any University of Arkansas president, spanning twenty-five years and ending only with his death in 1939. In this time period, Futrall successfully defended against the relocation of the university to Little Rock, the official accreditation of the college in the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools, survived two revolts, one by students and another by bankers, and oversaw the construction of most of the collegiate gothic buildings on campus.[30] The funding for the new buildings was made possible by a bonds from the state and resulted in the construction of the engineering and agricultural buildings in 1926 and 1927, respectively. The issue of money also lead Futrall to actively deciding to limit the post-graduate studies at the school. While the Graduate School was established in 1927, Futrall's decision to limit its cost, lead to no doctoral programs until after his death.[31]

The Bankers Agricultural revolt had its origin in 1919 when the Profitable Farming Bureau (PFB), an agency established by bankers in Little Rock, to promote further investment in agriculture, began to pressure Futrall and the Board of Directors on the issue of the university's College of Agriculture and extension services.[32] In effect, the PFB sought to place an individual educated in modern agricultural practices of the day, as well loyal to its purposes and aims, in charge of the department and its extension services; something that Futrall absolutely refused to consider. Under the growing stress placed on the university by the PFB, the financially tight Futrall and board, undertook the purchase of 423 acres (1.71 km2) of farm land at $123 an acre.[33] Futrall ultimately fended off the attempt by PFB to gain de facto control of the university's agricultural program by choosing a new dean who meet all the requirements that the PFB wanted, but one who was loyal to Futrall and not the agency.[34]

Not long after the conclusion of this battle, a new one ensued, this time concerning the removal of the university from Northwest Arkansas. It began with the introduction of a bill in the state House of Representatives, by a representative from Pope County, to break away the Colleges of Agriculture and Engineering and place them in Russellville. As part of the attempt, the proponents from Pope County had gained the support of individuals from Pulaski County, in exchange for assisting later with any attempts to move the school or parts of it to Little Rock. Both the university and Fayetteville fought the move, and the bill was successfully beaten back in a vote of 52 to 37. Despite the setback, new bills were submitted to time a statewide referendum on the matter with the holding of the 1924 Democrat primary. Proponents of the move went so far as to establish the Arkansas University Removal Association to lobby for a more successful result. Among the chief defenders of the university was Vol Walker and former governor Brough, and after hours and days of speeches for and against the move, the issue was silenced when the state Senate voted to indefinitely postpone any vote upon the bill urging the school's removal.[35]

By 1938, the growing university needed a student union building, and Futrall began charging a $2 per year "student union" fee. The result was Memorial Hall, one of three buildings funded by the Public Works Administration. The Home Economics Building and Classroom Building (part of what is now Ozark Hall) were also added.[36] The Jackson, Tennessee native would never see the final fruits of his labor, however, as Futrall died on September 12, 1939,[37] in an automobile accident on his way back from Little Rock. In addition to the aforementioned events of his time as president, he oversaw the creation of a student government, the expansion of student extracurricular activities, and the founding of the School of Law, amid other significant moments in the history of the school. The Board of Trustees passed a resolution to posthumously name the new student union building "Futrall Memorial Hall" in the president's honor.

The Second World War and after

During World War II, Arkansas was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[38]

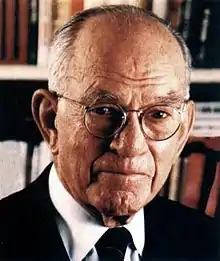

J. William Fulbright was selected after a short period by Governor Carl E. Bailey to assume the presidency of the university, a term that ended only two years later with his firing by Bailey's successor, Homer Adkins.[39] In the brief time that Fulbright was president, he essentially continued the policies left behind by the deceased Futrall, though for the first time, the school's stadium became known as Razorback Stadium.[40] Fulbright's termination came as a result of Adkins' election, who had promised to "[t]ake the University out of [p]olitics." As a result, Adkins with the assistance of the legislator, changed the process by which the board of trustees was elected, and followed that with the firing of a number of high-ranking individuals at the university. Fulbright later gained revenge on Adkins, by defeating the governor for the Senate seat in 1944.[41]

Arthur M. Harding was selected as the new president immediately following the firing of Fulbright, and kept the position until 1947. His term as president was markedly different than most of his predecessors, as the university underwent change to support the war effort. Such changes included the establishment of four quarter terms, instead of two semesters, barracks were built surrounding the university for military personnel, and the largest student group on campus was an army air corps unit.[42]

Harding was succeeded by Lewis Webster Jones, with the law school dean, Robert A. Leflar, serving in an interim capacity for a brief period of time. Under Harding, the Fine Arts Center was established on campus, as well the creation of a medical center, attached to the School of Medicine, situated in Little Rock. Doctoral programs, long avoided for cost during the Futrall years, were implemented in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[43] It was also during Jones' tenure that the university became the first white Southern university to allow the admission of an African-American since Reconstruction and the first ever to a post-graduate school, with the entry of Silas H. Hunt to the School of Law.[44] Jones departed the university in 1951 to assume the presidency of Rutgers University.[45] Hunt's enrollment at the University of Arkansas was also regarded as the first successful school integration in the United States below the Mason-Dixon Line.[46] The same year, the University of Arkansas Medical School would join the University's Law School in integrating as well.[47] Edith Irby Jones, who was also among the African Americans who enrolled at the University of Arkansas in 1948, would become not only the first African American to enroll at the University of Arkansas, but the first African American to enroll below at a standard school in the Southern states.[48][49] Despite Hunt's untimely death in 1949,[50] fellow Unverisity of Arkansas Law School student Jackie would become the first African American to graduate from the University of Arkansas in 1951.[51]

Assuming the job of university president in 1952 was John T. Caldwell. Caldwell began his term by completing a number of projects begun by his predecessor, such as the establishment of the School of Nursing. Despite a cool relationship with Governor Orval Faubus, the two never interfered with the other's realm, with the governor offering no opposition to the university's work at integrating its Fayetteville and Little Rock campuses.[52] Caldwell's replacement was David Wiley Mullins, of whom the present library is named for. Mullins formally became president in 1961 during the centennial of the Morrill Act, and oversaw the great burst of growth and expansion of the university during the twelve years of his administration.[53]

Under Mullins' watchful eye, most of the multiple story dormitories, now visibly present on the Fayetteville skyline were constructed, as well as the Graduate Education building, science and engineering buildings, and the now demolished Carlson terraces. A new student union was built with the old track and field space becoming an outdoor mall area, now situated between the library and the union, and the Fine Arts Center and the law school. Growth went beyond student enrollment and buildings with record private contributions flowing in to the tune of nearly three million dollars from 1962 to 1965.[54]

Modern era

Mullin's administration was followed by the presidency of Charles Edwin Bishop, who continued the building projects begun under his predecessor. The greatest impact of Bishop's tenure was the establishment of the University of Arkansas System, which re-organized a number of community colleges and state universities into a unified entity.[55] The next president, James E. Martin, went further with the creation of the chancellor position at the university, which in effect carried the roles and duties formerly possessed by the office of university president. In addition, the University of Arkansas Press was established during his tenure.[56]

Thus, in 1982, Bill Allen Nugent became the first chancellor of the university after 110 years, which then allowed university president Martin to focus on the university system.[57] Nugent was followed by Willard Badgett Gatewood Jr., best remembered for beginning the restoration of Old Main.[58] The position of university president was further separated from the school by Martin's successor, Ray Thornton, who moved the physical office to Little Rock to better oversee the unified university system. Thornton later resigned his position to run successfully for Congress, and was later elected a justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court.[59]

The university's third chancellor, Daniel Edward Ferritor, continued and completed the restoration of Old Main, during his eleven-year term. Chief among Ferritor's accomplishments was the addition of another two million square feet in classroom and laboratory space at a cost of $120 million, as well as boosting annual giving to the university from three million to twenty million dollars.[60] Following Ferritor was John A. White, perhaps best known for overseeing the Campaign for the 21st Century, which raised over one billion dollars for the university endowments over an eight-year period.[61] White resigned in 2008 following the tempestuous release of Houston Nutt from his position as the head coach of the school's football program. In a unanimous vote, the board of trustees elected G. David Gearhart to be the fifth chancellor in school history.[62]

References

- John Hugh Reynolds and David Yancey Thomas, History of the University of Arkansas (Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Press, 1910), p. 19.

- Reynolds, History of the University of Arkansas, p. 20

- Reynolds, History of the University of Arkansas, p. 27.

- Robert A. Leflar, The First 100 Years: Centennial History of the University of Arkansas,(Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas Foundation, Inc., 1972), p.5

- Leflar, The First 100 Years, p. 5.

- Leflar, The First 100 Years, p.6

- Reynolds, History of the University of Arkansas, p.57

- Leflar, The First 100 Years, p. 6-8

- Leflar, The First 100 Years, p. 8-9

- Reynolds, History of the University of Arkansas, p.70.

- Reynolds, History of the University of Arkansas, p.64.

- Reynolds, History of the University of Arkansas, p.70-71.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 14.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 16.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p.15-16.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 19-20.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 20.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 37-39.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 41-42.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 43-44.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 48.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 49-50.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 65.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 67.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 67-68.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 71 - 75.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 75.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 78 - 79.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 87-88.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 91.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 93-94.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 103.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 112.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 119-120.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 168-171.

- "Memorial Hall." University of Arkansas. Memorial Hall Profile. Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 101.

- "U.S. Naval Administration in World War II". HyperWar Foundation. 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 174.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 177.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 179-181.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 184-185.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 188-189.

- "Silas Herbert Hunt (1922–1949) - Encyclopedia of Arkansas". www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 189.

- "Before Little Rock: Successful Arkansas School Integration". University of Arkansas. September 10, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- "Before Little Rock: Successful Arkansas School Integration".

- Moon, Henry Lee, ed. (November 1970). "University of Arkansas Is First". The Crisis. New York, NY: The Crisis Publishing Company, Inc. 77 (9): 331–332. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- "Edith Irby Jones, M.D." Bethesda, Maryland: National Library of Medicine. 2005. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- "First Negro Admitted to Arkansas U. Dies". No. 53:220. Joplin Globe Publishing Co. Joplin Globe. April 23, 1949.

- Kilpatrick, Judith (Summer 2009). "Desegregating the University of Arkansas School of Law: L. Clifford Davis and the Six Pioneers" (PDF). The Arkansas Historical Quarterly,VOL. LXVIII, NO. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 195, 198 - 199.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 203-204.

- Leflar, The First One Hundred Years, p. 204-206.

- "University of Arkansas - Office of the Chancellor - Bishop Entry". uark.edu.

- "University of Arkansas - Office of the Chancellor - Martin entry". uark.edu. Archived from the original on 2009-08-22. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- "University of Arkansas - Office of the Chancellor - Nugent entry". uark.edu.

- "University of Arkansas - Office of the Chancellor - Gatewood entry". uark.edu.

- "University of Arkansas - Office of the Chancellor - Thornton Entry". uark.edu.

- "University of Arkansas - Office of the Chancellor - Ferritor Entry". uark.edu.

- "- University of Arkansas - Office of the Chancellor - White Entry". uark.edu.

- "University of Arkansas - Daily Headlines Trustees Unanimously Approve G. David Gearhart as Fifth Chancellor of University of Arkansas 2/25/08". Archived from the original on 2008-08-08. Retrieved 2009-06-21.