History of the Macedonian language

The history of the Macedonian language refers to the developmental periods of current-day Macedonian, an Eastern South Slavic language spoken on the territory of North Macedonia. The Macedonian language developed during the middle ages from the Old Church Slavonic, the common language spoken by Slavic people.

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

In 1903 Krste Petkov Misirkov was the first to argue for the codification of a standard literary Macedonian language in his book Za makedonckite raboti (On Macedonian Matters). Standard Macedonian was formally proclaimed an official language on 2 August 1944 by the Anti-Fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM). Its codification followed in the year after.

According to Macedonian scholars, the history of the Macedonian language can be divided into nine developmental stages.[1][2] Blaže Koneski distinguishes two different periods in the development of the Macedonian language, namely, old from the 12th to the 15th century and modern after the 15th century.[3] According to the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts (MANU), the development of the Macedonian language involved two different scripts, namely the Glagolitic and Cyrillic scripts.[4]

Overview of periods

Medieval

For many centuries, Slavic people who settled on the Balkans spoke their own dialects and used other dialects or languages to communicate with other people.[5] The "canonical" Old Church Slavonic period of the development of Macedonian started in the 9th century and lasted until the first half of the 11th century. During this period common to all Slavic languages, Greek religious texts were translated to Old Church Slavonic (based on a dialect spoken in Thessaloniki).[1][6][7] The Macedonian recension of Old Church Slavonic also appeared around that period in the First Bulgarian Empire and was referred to as such due to works of the Ohrid Literary School, with its seat in Ohrid, current-day North Macedonia.[8]

The 11th century saw the fall of the Proto-Slavic linguistic unity and the rise of Macedonian dialects, which were still within the borders of the Bulgarian-Macedonian dialect continuum.[9] The Macedonian recension of Church Slavonic developed between the 11th and 13th century and during this period, in addition to translation of canonical texts, religious passages were created including praising texts and sermons (слова/беседи) of saints such as Saint Clement of Ohrid. These texts use linguistic features different from Church Slavonic and since the language was characteristic of the region of current-day North Macedonia, this variant can also be referred to as Old Macedonian Church Slavonic.[10]

This period, whose span also included the Ottoman conquest, witnessed grammatical and linguistic changes that came to characterize Macedonian as a member of the Balkan sprachbund.[10][1] This marked a dialectal differentiation of the Macedonian language in the 13th century that largely reflected Slavic and Balkan characteristics and saw the formation of dialects that are preserved in modern-day Macedonian.[5][9] During the five centuries of Ottoman rule in Macedonia, loanwords from Turkish entered the Macedonian language, which by extension had an Arabo-Persian origin.[11] While the written language remained static as a result of Turkish domination, the spoken dialects moved further apart. Only very slight traces of texts written in the Macedonian language survive from the 16th and 17th centuries.[12] The first printed work that included written specimens of the Macedonian language was a multilingual "conversational manual", that was printed during the Ottoman era.[13] It was published in 1793 and contained texts written by a priest in the dialect of the Ohrid region. In the Ottoman Empire, religion was the primary means of social differentiation, with Muslims forming the ruling class and non-Muslims the subordinate classes.[14] In the period between the 14th and 18th century, the Serbian recension of Church Slavonic prevailed on the territory and elements of the vernacular language started entering the language of church literature from the 16th century.[9]

The earliest lexicographic evidence of the Macedonian dialects, described as Bulgarian,[15][16] can be found in a lexicon from the 16th century written in the Greek alphabet.[17] The concept of the various Macedonian dialects as a part of the Bulgarian language can be seen also from early vernacular texts from Macedonia such as the four-language dictionary of Daniel Moscopolites, the works of Kiril Peichinovich and Yoakim Karchovski, and some vernacular gospels written in the Greek alphabet. These written works influenced by or completely written in the local Slavic vernacular appeared in Macedonia in the 18th and beginning of the 19th century and their authors referred to their language as Bulgarian.[18]

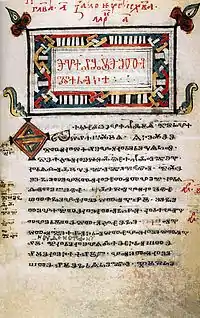

The earliest texts showing specifically Macedonian phonetic features are Old Church Slavonic classical texts written in Glagolitic which date from the 10th to 11th centuries (Codex Zographensis, Codex Assemanianus, Psalterium Sinaiticum). By the 12th century the Church Slavonic Cyrillic become the main alphabet. Texts reflecting vernacular Macedonian language features appear in the second half of the 16th century (translations of the sermons of the Greek writer Damascene Studite).[19]

Modern era

The latter half of the 18th century saw the rise of modern literary Macedonian. Macedonian dialects started being used during this period for ecclesiastical and didactic works although the vernacular used was referred to as "Bulgarian" by writers.[10] Writers of that period, namely Joakim Krchovski and Kiril Pejchinovik opted for writing in their dialects since they wanted to make the language of the first printed books understandable to the people. The southern half of the Macedonian dialectal territory in Aegean Macedonia used the Greek alphabet.[9] The first half of the 19th century saw the rise of nationalism among South Slavs under the Ottoman Empire.[20] Bulgarian and Macedonian Slavs wanted to create their own Church and schools, which would use a common modern Macedono-Bulgarian literary standard.[21][22] The national elites active at that time used mainly ethnolinguistic principles to differentiate between Slavic-Bulgarian and Greek groups.[23] Initially, every ethnographic subgroup in the Macedonian-Bulgarian linguistic area wrote in its own local dialect and choosing a "base dialect" for the new standard was not an issue.[24]

During the period between 1840 and 1870, there was a struggle to define a dialectal base of the vernacular used, with two different literary centers arising - one in current-day northeastern Bulgaria and one in current-day southwestern North Macedonia. The two centers had opposing views concerning the dialectal basis that should be used as the new common standard language for the Macedonian and Bulgarian Slavic people due to the vast differences between western Macedonian and eastern Bulgarian dialects.[21] During this period, Macedonian intellectuals who proposed the creation of a Bulgarian literary language based on Macedonian dialects emerged.[10]

By the early 1870s, an independent Bulgarian autocepholous church and a separate Bulgarian ethnic community was recognized by the Ottoman authorities. Linguistic proposals for a common language were rejected by the Bulgarian Movement, proclaiming Macedonian a "degenerate dialect" and stating that Macedonian Slavs should learn standard Bulgarian.[21] The same period also saw the rise of the "Macedonists" who argued that the Macedonian language should be used for the Macedonian Slavs, who they saw as a distinct people on the Balkans.[25] Poetry written in the Struga dialect with elements from Russian also appeared.[9] At that time, textbooks were also published and they used either spoken dialectal forms of the language or a mixed Bulgarian-Macedonian language.[25]

Revival era

In 1875, Gjorgji Pulevski, in Belgrade published a book called Dictionary of Three Languages (Rečnik od tri jezika, Речник од три језика) which was a phrasebook composed in a "question-and-answer" style in Macedonian, Albanian and Turkish, all three spelled in Cyrillic. Pulevski wrote in his native eastern Tarnovo dialect and his language was an attempt at creating a supra-dialectal Macedonian norm, based on his own native local Galičnik dialect. This marked the first pro-Macedonian views expressed in print.[26]

Between 1892 and 1894 the maganize Loza, which was run by IMRO revolutionaries, used a distinct style of writing for their monthly magazine: they dropped the usage of the letter ya (Я) and big yus (Ѫ) and instead used the letter i for je (J), while also taking some inspiration from Serbian grammar.[27]

Krste Petkov Misirkov's book Za makedonckite raboti (On Macedonian Matters) published in 1903, is the first attempt to create a separate literary language.[21] With the book, the author proposed a Macedonian grammar and expressed the goal of codifying the language and using it in schools. The author postulated the principle that the Prilep-Bitola dialect be used as a dialectal basis for the formation of the Macedonian standard language; his idea however was not adopted until the 1940s.[10][9] The book was met with opposition and initial prints at the printing press in Sofia were destroyed.[21][26][28]

Prior to the codification of the standard languages (incl. Standard Macedonian), the boundaries between the South Slavic languages had yet to be "conceptualized in modern terms" and the linguistic norms were still in the process of development (including the Bulgarian standard language).[29][25] Thus, the creation of boundaries within the South Slavic linguistic continuum is "relatively recent", with the distinction between Bulgarian and Serbian still being contested in 1822 among European Slavists.[26]

The period after the First Balkan War and between the two World Wars saw linguists outside the Balkans publishing studies to emphasize that Macedonian is a language distinct from Serbo-Croatian and Bulgarian.[10] In the interwar period, the territory of today's North Macedonia became part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the local vernacular fell under the influence of Serbo-Croatian.[30] In 1934, the Comintern issued a resolution which supported the codification of a separate Macedonian language.[31] During the World wars Bulgaria's short annexations over Macedonia saw two attempts to bring the Macedonian dialects back towards Bulgarian linguistic influence.[32]

Codification

On 2 August 1944 at the first Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) meeting, the Macedonian language was declared an official language.[10][28] With this, Macedonian became the last of the major Slavic languages to achieve a standard literary form.[6] As such, it served as one of the three official languages of Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1991.[4] The first official Macedonian grammar was developed by Krume Kepeski in 1946. One of the most important contributors in the standardisation of the Macedonian literary language was Blaže Koneski. Most of the codification of Standard Macedonian took place between 1945 and 1950 (Friedman, 1998). Some contemporary linguists argued that during its codification, the Macedonian language was Serbianized, specifically in terms of its orthography.[33][34][35][36][37] The standardization of Macedonian established a second standard language within a dialect continuum comprising Macedonian, Bulgarian and the Torlakian dialects,[38] itself a legacy of the linguistic developments during the height of the Preslav and Ohrid literary schools.[39] There are some researchers who hold that the standardization of Macedonian was done with the need to differentiate from Serbian and Bulgarian in mind but the dialects chosen for the base of the standard language had never yet been covered by an existing standard, so the codification of Macedonian was not exactly a separation from an existing pluricentric language.[40] Some argue that the codification was done intentionally on the variant most unlike Standard Bulgarian (i.e. the Prilep-Bitola dialect),[41] while others argue that this view does not take into account the fact that a Macedonian koiné language was already in existence.[42] The policy is argued to stem from the works of Misirkov, who suggested that Standard Macedonian should abstract on those dialects "most distinct from the standards of the other Slavonic languages".[43]

After the Tito–Stalin split in 1948, under the auspices of some Aegean Macedonian intellectuals in Bucharest, anti-Yugoslav alphabet, grammar, and primer closer to Bulgarian, and purified of the Serbo-Croatian loanwords of the language of Skopje, were created.[44][45] The Communist Party of Greece led by Nikos Zahariadis took the side of the Cominform. After the defeat of communists in the Greek Civil War in 1949, a hunt for Titoist spies began in the midst of Greek political immigrants - civil war refugees, living in socialist countries in Eastern Europe. As a result the Greek communist publisher "Nea Ellada" issued a Macedonian grammar (1952) and developed a different alphabet. Between 1952 and 1956, the Macedonian Department of "Nea Ellada" published a number of issues in this literary standard, officially called "Macedonian language of the Slavomacedonians from Greek or Aegean Macedonia". This failed attempt of codification included the Ъ, Ь, Ю, Я, Й and was merely a linguistic norm of the Bulgarian language.[46] The grammar was prepared by a team headed by Atanas Peykov.[47] This "Aegean Macedonian language" facilitated the later spread of the standard Yugoslav Macedonian norm among the Aegean emigrants. Greek refugees educated in this norm were nearly unable to adopt the Yugoslav version later. The Soviet-Yugoslav rapprochement from the mid-1950s helped to put this codification to an end.[45] The end of Moscow's support for the contestation of standard Macedonian's legitimacy from abroad coincided with the period of excerption for the Macedonian dictionary of Blaže Koneski, which according to Christian Voss, marked the turning poing of the Serbianisation of Macedonian.[35] Thus, the Aegean codification did not gain widespread acceptance.[48] However, the printed editions of the refugees from Aegean Macedonia in Eastern Europe published until 1977 continued to be written in this linguistic norm.

History of the Macedonian alphabet

In the 19th and first half of the 20th century, Macedonian writers started writing texts in their own Macedonian dialects using Bulgarian and Serbian Cyrillic scripts. In South Macedonia, the Greek alphabet was also widespread and used by Macedonian writers who finished their education at Greek schools.[55] The period between the two World Wars saw the usage of the alphabets of the surrounding countries including the Albanian one depending on where the writers came from. During that period, the typewriter available to writers was also a determining factor for which alphabet would be used.[56] The official Macedonian alphabet was codified on 5 May 1945 by the Presidium of the Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia (abbreviated as ASNOM in Macedonian) headed by Blaže Koneski.[57]

Political views on the language through history

Recognition

Politicians and scholars from North Macedonia, Bulgaria and Greece have opposing views about the existence and distinctiveness of the Macedonian language. Through history and especially before its codification, Macedonian has been referred to as a variant of Bulgarian,[58] Serbian[42] or a distinct language of its own.[59][60] During the late 19th/early 20th century, Greeks claimed that Macedonian dialects were "a corrupted version of ancient Macedonian".[61] Historically, after its codification, the use of the language has been a subject of different views in Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece. In the interwar period, Macedonian was treated as a South Serbian dialect in Yugoslavia in accordance with claims made in the 19th century but the government permitted its use in dialectal literature.[10] The 1940s saw opposing views on the Macedonian language in Bulgaria; while its existence was recognized in 1946-47 and allowed as the language of instruction in schools in Pirin Macedonia, the period after 1948 saw its rejection and restricted domestic use.[21]

Until 1999, Macedonian had never been recognized as a minority language in Greece and attempts to have Macedonian-language books introduced in education have failed.[21] For instance, a Macedonian primer Abecedar was published in 1925 in Athens but was never used and eventually, most copies were destroyed.[10] Professor Christina Kramer argues that Greek policies have largely been based on denying connection between the Macedonian codified standard and that of the Slavophone minority in the country and sees it as "clearly directed towards the elimination of Macedonian".[21] The number of speakers of Macedonian in Greece has been difficult to establish since part of the Slavophone Greek population is also considered speakers of Bulgarian by Bulgarian linguists.[58][62][63] In recent years, there have been attempts to have the language recognized as a minority language in Greece.[64] In Albania, Macedonian was recognized after 1946 and mother-tongue instructions were offered in some village schools until grade four.[21]

Autonomous language dispute

Bulgarian scholars have and continue to widely consider Macedonian part of the Bulgarian dialect area. In many Bulgarian and international sources before the World War II, the South Slavic dialect continuum covering the area of today's North Macedonia and Northern Greece was referred to as a group of Bulgarian dialects. Some scholars argue that the idea of linguistic separatism emerged in the late 19th century with the advent of Macedonian nationalism and the need for a separate Macedonian standard language subsequently appeared in the early 20th century.[65][66] Local variants used to name the language were also balgàrtzki, bùgarski or bugàrski; i.e. Bulgarian.[67]

Although Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the independence of the Republic of Macedonia, most of its academics, as well as the general public, regarded the language spoken there as a form of Bulgarian. Dialect experts of the Bulgarian language refer to the Macedonian language as македонска езикова форма i.e. Macedonian linguistic norm of the Bulgarian language.[68] In 1999 the government in Sofia signed a Joint Declaration in the official languages of the two countries, marking the first time it agreed to sign a bilateral agreement written in Macedonian.[21] As of 2019, disputes regarding the language and its origins are ongoing in academic and political circles in the countries. Macedonian is still widely regarded as a dialect by Bulgarian scholars, historians and politicians alike including the Government of Bulgaria and the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, which denies the existence of a separate Macedonian language and declares it a written regional form of the Bulgarian language.[69][70] Similar sentiments are also expressed by the majority of the Bulgarian population.[25] The current international consensus outside of Bulgaria is that Macedonian is an autonomous language within the Eastern South Slavic dialect continuum.[68][71] As such, the language is recognized by 138 countries of the United Nations.[4]

Naming dispute

The Greek scientific and local community was opposed to using the denomination Macedonian to refer to the language in light of the Greek-Macedonian naming dispute. The term is often avoided in the Greek context, and vehemently rejected by most Greeks, for whom Macedonian has very different connotations. Instead, the language is often called simply "Slavic" or "Slavomacedonian" (translated to "Macedonian Slavic" in English). Speakers themselves variously refer to their language as makedonski, makedoniski ("Macedonian"),[72] slaviká (Greek: σλαβικά, "Slavic"), dópia or entópia (Greek: εντόπια, "local/indigenous [language]"),[73] balgàrtzki (Bulgarian) or "Macedonian" in some parts of the region of Kastoria,[74] bògartski ("Bulgarian") in some parts of Dolna Prespa[67] along with naši ("our own") and stariski ("old").[75] With the Prespa agreement signed in 2018 between the Government of North Macedonia and the Government of Greece, the latter country accepted the use of the adjective Macedonian to refer to the language using a footnote to describe it as Slavic.[76]

Gallery

The 11th century Codex Zographensis, a text written in Old Church Slavonic using the Glagolitic writing system.

The 11th century Codex Zographensis, a text written in Old Church Slavonic using the Glagolitic writing system. Cyrillic manuscript in Church Slavonic from the 13th century found in Vranestica.

Cyrillic manuscript in Church Slavonic from the 13th century found in Vranestica..jpg.webp) Page from a Bulgarian-Greek dictionary from the 16th century written in Greek letters in Kostur dialect.

Page from a Bulgarian-Greek dictionary from the 16th century written in Greek letters in Kostur dialect.

Marko Teodorrovic's primer. Teodorovic, who was Bulgarian from Bansko, printed it in 1792 in mixture of Church Slavonic and vernacular in Belgrade.

Marko Teodorrovic's primer. Teodorovic, who was Bulgarian from Bansko, printed it in 1792 in mixture of Church Slavonic and vernacular in Belgrade. Yoakim Karchovski's vernacular book, 1814. Per its author it was written in "the plainest Bulgarian language".

Yoakim Karchovski's vernacular book, 1814. Per its author it was written in "the plainest Bulgarian language". Konikovo Gospel, 1852 typed with Greek letters in vernacular. On the title page is inscription "Written in Bulgarian language".

Konikovo Gospel, 1852 typed with Greek letters in vernacular. On the title page is inscription "Written in Bulgarian language". Kulakia Gospel, 1863. It represents translation from Greek evangeliarium to Solun-Voden dialect and was written by hand with Greek letters from Evstati Kipriadi in "Bulgarian language".

Kulakia Gospel, 1863. It represents translation from Greek evangeliarium to Solun-Voden dialect and was written by hand with Greek letters from Evstati Kipriadi in "Bulgarian language". "A Dictionary of Three languages" published by Gjorgjija Pulevski in 1875 in Belgrade. It presented Macedonian, Albanian and Turkish.

"A Dictionary of Three languages" published by Gjorgjija Pulevski in 1875 in Belgrade. It presented Macedonian, Albanian and Turkish. The Young Macedonian Literary Society magazine Loza issued in 1891. Its appeal was to present the Macedonian dialects much more in the standard Bulgarian language. The magazine was banned as separatist by the authorities.

The Young Macedonian Literary Society magazine Loza issued in 1891. Its appeal was to present the Macedonian dialects much more in the standard Bulgarian language. The magazine was banned as separatist by the authorities. Front cover of Za Makedonckite Raboti. In 1903 Krste Misirkov argued for the codification of a standard literary Macedonian language in it.

Front cover of Za Makedonckite Raboti. In 1903 Krste Misirkov argued for the codification of a standard literary Macedonian language in it. "Abecedar" was a primer prepared by the Greek government in 1925, intended for the Slavic speaking minority in Greek Macedonia.

"Abecedar" was a primer prepared by the Greek government in 1925, intended for the Slavic speaking minority in Greek Macedonia. Issue of the IMRO newspaper "Svoboda ili smart" from April 1933. All official documents of the Macedonian revolutionary organization from its foundation in 1893 until its ban in 1934 were in standard Bulgarian.

Issue of the IMRO newspaper "Svoboda ili smart" from April 1933. All official documents of the Macedonian revolutionary organization from its foundation in 1893 until its ban in 1934 were in standard Bulgarian.

References

- Spasov, Ljudmil (2007). "Периодизација на историјата на македонскиот писмен јазик и неговата стандардизација во дваесеттиот век" [Periodization of the history of the Macedonian literary language and its standardization in the twentieth century]. Filološki Studii (in Macedonian). Skopje: St. Cyril and Methodius University. 5 (1): 229–235. ISSN 1857-6060.

- Koneski, Blazhe (1967). Историја на македонскиот јазик [History of the Macedonian Language] (in Macedonian). Skopje: Kultura.

- Friedman 2001, p. 435

- "Повелба за македонскиот јазик" [Charter for the Macedonian language] (PDF) (in Macedonian). Skopje: Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Usikova 2005, p. 103

- Browne, Wayles; Vsevolodovich Ivanov, Vyacheslav. "Slavic languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Old Church Slavonic language". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Horace Gray Lunt, Old Church Slavonic Grammar, Walter de Gruyter, 2001. ISBN 3110162849, p. 4.

- Usikova 2005, p. 106

- Friedman 2001, p. 436

- Friedman 2001, p. 438

- Lunt, H. (1953) "A Survey of Macedonian Literature" in Harvard Slavic Studies, Vol. 1, pp. 363-396

- Lunt, H. (1952) Grammar of the Macedonian Literary Language (Skopje)

- Lunt, H. (1986) "On Macedonian Nationality" in Slavic Review, Vol. 45, pp. 729-734

- "Bulgarians" were they called by the Greeks of Macedonia and "Bulgarian" was their dialect termed, as is shown by the 16th century "Macedonian Dictionary", a glossary of 301 Slavic words and phrases that were current in the region of Kastoria. For more see: Nikolaos P. Andriōtēs, The Federative Republic of Skopje and its language, Volume 77 of Macedonian Bibliotheca, Edition 2, Society for Macedonian Studies, 1991, p. 19.

- The dictionary presented in the monument includes words and expressions apparently collected for the purpose of direct communication. It is a manual drawn up by a Greek who has visited settlements where he had to communicate with the local population... The dictionary homepage states: ἀρхὴἐ ν βοσλγαρίοις ριμά τον εἰςκῑ νῆ γλόταἐ pointed out by Al.Nichev, kῑλῆ ὴγιῶηηα' (Nichev 1085, p. 8), i.e.,'koine language', common language in the sense of "national language". This heading of the dictionary Al. Nitchev translates as 'The beginning of words by the Bulgarians, which (words) refer to the vernacular'... The designation of the dictionary as "Bulgarian words" is written not in the original dialect but is in Greek language and should not have been transmitted as a title in Bulgarian. However, the designation "Bulgarian words" translates well the original Greek designation "Βουλγάρος ρήματα", because of which I accept and use this title, with the proviso that it is translated from Greek. For more see: Лилия Илиева, Българският език в предисторията на компаративната лингвистика и в езиковия свят на ранния европейски модернизъм, Университетско издателство „Неофит Рилски“, Благоевград; ISBN 978-954-680-768-7, 2011, стр. 53-55. Lilia Ilieva, Bulgarian in the Prehistory of Comparative Linguistics and in the Linguistic World of Early European Modernism, University Publishing House "Neofit Rilski", Blagoevgrad; ISBN 978-954-680-768-7, 2011, pp. 53-55.(in Bulgarian).

- 'Un Lexique Macedonien Du XVIe Siecle', Giannelli, Ciro. Avec la collaboration de Andre Vaillant, 1958

- F. A. K. Yasamee "NATIONALITY IN THE BALKANS: THE CASE OF THE MACEDONIANS" in Balkans: A Mirror of the New World Order, Istanbul: EREN, 1995; pp. 121–132.

- Price, G. (2000) Encyclopedia of the Languages of Europe. (Oxford : Blackwell) ISBN 0-631-22039-9

- Detrez, Raymond; Segaert, Barbara; Lang, Peter (2008). Europe and the Historical Legacies in the Balkans. Peter Lang. pp. 36–38. ISBN 978-90-5201-374-9. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Kramer 1999, p. ?

- Bechev, Dimitar (13 April 2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia Historical Dictionaries of Europe. Scarecrow Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8108-6295-1. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Theodora Dragostinova, From Rum Millet to Greek and Bulgarian Nations: Religious and National Debates in the Borderlands of the Ottoman Empire, 1870–1913. Ohio State University, 2011, Columbus, OH.

- "Венедиктов Г. К. Болгарский литературный язык эпохи Возрождения. Проблемы нормализации и выбора диалектной основы. Отв. ред. Л. Н. Смирнов. М.: "Наука"" (PDF). 1990. pp. 163–170. (Rus.). Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Nihtinen 1999, p. ?

- Victor A. Friedman (1975). "Macedonian language and nationalism during the 19th and early 20th centuries" (PDF). Balcanistica. 2: 83–98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Loza Magazines between 1892 and 1894

- Pejoska-Bouchereau 2008, p. 146

- Joseph, Brian D. et al. When Languages Collide: Perspectives on Language Conflict, Competition and Coexistence; Ohio State University Press (2002), p.261

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (15 March 1995). Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 143. ISBN 0-312-12116-4. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Duncan Perry, "The Republic of Macedonia: finding its way" in Karen Dawisha and Bruce Parrot (eds.), Politics, power and the struggle for Democracy in South-Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 228-229.

- Thammy Evans, Philip Briggs, North Macedonia; Bradt Travel Guides, 2019; ISBN 1784770841, p. 47.

- Friedman 1998, p. ?

- Marinov, Tchavdar (25 May 2010). "Historiographical Revisionism and Re-Articulation of Memory in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (PDF). Sociétés politiques comparées. 25: 7. S2CID 174770777. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2020.

- Voss C., The Macedonian Standard Language: Tito—Yugoslav Experiment or Symbol of "Great Macedonian" Ethnic Inclusion? in C. Mar-Molinero, P. Stevenson as ed. Language Ideologies, Policies and Practices: Language and the Future of Europe, Springer, 2016, ISBN 0230523889, p. 126.

- De Gruyter as contributor. The Slavic Languages. Volume 32 of Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science (HSK), Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, 2014, p. 1472. ISBN 3110215470.

- Lerner W. Goetingen, Formation of the standard language - Macedonian in the Slavic languages, Volume 32, Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, 2014, ISBN 3110393689, chapter 109.

- The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide. 27 July 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Florin Curta. Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages; 500–1250. ; Cambridge. Pg 216

- Sussex, Roland; Cubberley, Paul (2006). The Slavic Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 70. ISBN 1139457284.

- Trudgill, Peter (2002). Sociolinguistic variation and change. Edinburgh University Press. p. 120. ISBN 0-7486-1515-6. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Comrie & Corbett 2002, p. 251

- Dedaić, Mirjana N. et al. South Slavic Discourse Particles; John Benjamins Publishing (2010) p. 13

- Keith Brown, Macedonia's Child-grandfathers: The Transnational Politics of Memory, Exile, and Return, 1948-1998; Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies, University of Washington, 2003, p. 32.

- Roumen Daskalov, Tchavdar Marinov, Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies; BRILL, 2013; ISBN 900425076X, p. 480.

- Euangelos Kōphos, Speros Basil Vryonis, Nationalism and communism in Macedonia: civil conflict, politics of mutation, national identity; Center for the Study of Hellenism, A. D. Caratzas, 1993, ISBN 0892415401, p. 203.

- The Macedonian Times, issues 51–62; MI-AN, 1999, p. 141.

- Sebastian Kempgen, Peter Kosta, Tilman Berger, Karl Gutschmidt as ed., The Slavic Languages. Volume 32 of Handbooks of Linguistics and Communication Science (HSK) Walter de Gruyter, 2014; ISBN 3110215470, p. 1476.

- Проф. д-р Антони Стоилов и колектив, Крайно време е за сътрудничество. За езиковия спор, македонската литературна норма, Мисирков и възможностите за сътрудничество между езиковедите от Република Македония и Република България във В-к Култура - Брой 28 (2908), 21 юли 2017 г.

- Стефан Дечев: Българските и македонски политици задминаха националните историци; списание Marginalia, 24.06.2019 г.

- Кочев, Иван, Александров Иван, Документи за съчиняването на „македонския книжовен език", сп. Македонски преглед, Македонски научен институт, стр. 5-22; кн. 4. 1991 г.

- When Blaze Koneski, the founder of the Macedonian standard language, as a young boy, returned to his Macedonian native village from the Serbian town where he went to school, he was ridiculed for his Serbianized language. Cornelis H. van Schooneveld, Linguarum: Series maior, Issue 20, Mouton., 1966, p. 295.

- ...However this was not at all the case, as Koneski himself testifies. The use of the schwa is one of the most important points of dispute not only between Bulgarians and Macedonians, but also between Macedonians themselves – there are circles in Macedonia who in the beginning of the 1990s denounced its exclusion from the standard language as a hostile act of violent serbianization. For more see: Alexandra Ioannidou (Athens, Jena) Koneski, his successors and the peculiar narrative of a "late standardization" in the Balkans. in Romanica et Balcanica: Wolfgang Dahmen zum 65. Geburtstag, Volume 7 of Jenaer Beiträge zur Romanistik with Thede Kahl, Johannes Kramer and Elton Prifti as ed., Akademische Verlagsgemeinschaft München AVM, 2015, ISBN 3954770369, pp. 367-375.

- Kronsteiner, Otto, Zerfall Jugoslawiens und die Zukunft der makedonischen Literatursprache: Der späte Fall von Glottotomie? in: Die slawischen Sprachen (1992) 29, 142-171.

- Usikova 2005, p. 105.

- E. Kramer, Christina (January 2015). "Macedonian orthographic controversies". Written Language & Literacy. 18 (2): 287–308. doi:10.1075/wll.18.2.07kra.

- "Со решение на АСНОМ: 72 години од усвојувањето на македонската азбука". Javno (in Macedonian). 5 May 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- Institute of Bulgarian Language (1978). Единството на българския език в миналото и днес [The unity of the Bulgarian language in the past and today] (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 4. OCLC 6430481.

- Max K. Adler. Marxist Linguistic Theory and Communist Practice: A Sociolinguistic Study; Buske Verlag (1980), p.215

- Seriot 1997, pp. 270–271

- Alexis Heraclides (2021). The Macedonian Question And The Macedonians. Taylor & Francis. p. 152.

- Shklifov, Blagoy (1995). Проблеми на българската диалектна и историческа фонетика с оглед на македонските говори (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Kacharmazov. p. 14.

- Shklifov, Blagoy (1977). Речник на костурския говор, Българска диалектология (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Book VIII. pp. 201–205.

- "Report of the independent expert on minority issues, Gay McDougall Mission to Greece 8–16 September 2008" (PDF). Greek Helsinki Monitor. United Nations Human Rights Council. 18 February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2011.

- Fishman, Joshua A.; de Gruyter, Walter (1993). The Earliest Stage of Language Planning: The "First Congress" Phenomenon. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 161–162. ISBN 3-11-013530-2. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Danforth, Loring M. (1995). The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world. Princeton University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-691-04356-6. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Shklifov, Blagoy; Shklifova, Ekaterina (2003). Български деалектни текстове от Егейска Македония [Bulgarian dialect texts from Aegean Macedonia] (in Bulgarian). Sofia. pp. 28–36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Reimann, Daniel (2014). Kontrastive Linguistik und Fremdsprachendidaktik Iberoromanisch (in German). Gunter Narr Verlag. ISBN 978-3823368250.

- "Bulgarian Academy of Sciences is firm that "Macedonian language" is Bulgarian dialect". Bulgarian National Radio. 12 November 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Jakov Marusic, Sinisa (10 October 2019). "Bulgaria Sets Tough Terms for North Macedonia's EU Progress". Balkan Insights. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Trudgill 1992, p. ?

- Lois Whitman (1994): Denying ethnic identity: The Macedonians of Greece Helsinki Human Rights Watch. p.39 at Google Books

- "Greek Helsinki Monitor – Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities". Archived from the original on 23 May 2003. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- Danforth, Loring M. The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. p. 62. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Whitman, Lois (1994). Denying ethnic identity: The Macedonians of Greece. Helsinki Human Rights Watch. p. 37. ISBN 1564321320.

- "Republic of North Macedonia with Macedonian language and identity, says Greek media". Meta.mk. Meta. 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- Friedman, V. (1998) "The implementation of standard Macedonian: problems and results" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language, Vol. 131, pp. 31-57

- Topolinjska, Z. (1998) "In place of a foreword: facts about the Republic of Macedonia and the Macedonian language" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language, Vol. 131, pp. 1-11

- Friedman, V. (1985) "The sociolinguistics of literary Macedonian" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language, Vol. 52, pp. 31-57

- Tomić, O. (1991) "Macedonian as an Ausbau language" in Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations, pp. 437-454

- Mahon, M. (1998) "The Macedonian question in Bulgaria" in Nations and Nationalism, Vol. 4, pp. 389-407

Bibliography

- Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville (2002), "The Macedonian language", The Slavonic Languages, New York: Routledge Publications

- Friedman, Victor (1998), "The implementation of standard Macedonian: problems and results", International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 131: 31–57, doi:10.1515/ijsl.1998.131.31, S2CID 143891784

- Friedman, Victor (2001), Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.), Macedonian: Facts about the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the Worlds Major Languages, Past and Present (PDF), New York: Holt, pp. 435–439

- Nihtinen, Atina (1999), "Language, Cultural Identity and Politics in the Cases of Macedonian and Scots", Slavonica, 5 (1): 46–58, doi:10.1179/sla.1999.5.1.46

- Pejoska-Bouchereau, Frosa (2008), "Histoire de la langue macédonienne" [History of the Macedonian language], Revue des Études Slaves (in French), pp. 145–161

- Seriot, Patrick (1997), "Faut-il que les langues aient un nom? Le cas du macédonien" [Do languages have to have a name? The case of Macedonian], in Tabouret-Keller, Andrée (ed.), Le nom des langues. L'enjeu de la nomination des langues (in French), vol. 1, Louvain: Peeters, pp. 167–190, archived from the original on 5 September 2001

- Trudgill, Peter (1992), "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe", International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2 (2): 167–177, doi:10.1111/j.1473-4192.1992.tb00031.x

- Usikova, Rina Pavlovna (2005), Языки мира. Славянские языки: Македонский язык [Languages of the world. Slavic languages: Macedonian language] (in Russian), Moscow: Academia, pp. 102–139, ISBN 5-87444-216-2

- Kramer, Christina (1999), "Official Language, Minority Language, No Language at All: The History of Macedonian in Primary Education in the Balkans", Language Problems and Language Planning, 23 (3): 233–250, doi:10.1075/lplp.23.3.03kra

External links

- The first phonological conference for Macedonian with short history, Victor Friedman.

- Dictionary of Three Languages by Georgi Pulevski (1875)