History of North Macedonia

The history of North Macedonia encompasses the history of the territory of the modern state of North Macedonia.

Prehistory

Ancient period

.svg.png.webp)

Paeonians and other tribes

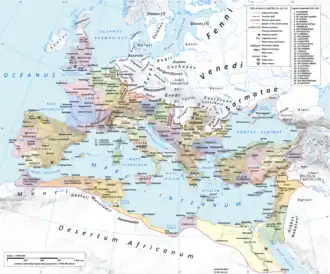

In antiquity, most of the territory that is now North Macedonia was included in the kingdom of Paeonia, which was populated by the Paeonians, a people of Thracian origins,[1] but also parts of ancient Illyria,[2][3] Ancient Macedonians populated the area in the south, living among many other tribes and Dardania,[4] inhabited by various Illyrian peoples,[5][6] and Lyncestis and Pelagonia populated by the ancient Greek Molossian[7] tribes. None of these had fixed boundaries; they were sometimes subject to the Kings of Macedon, and sometimes broke away.

Persian rule

In the late 6th century BC, the Achaemenid Persians under Darius the Great conquered the Paeonians, incorporating what is today North Macedonia within their vast territories.[8][9][10] Following the loss in the Second Persian invasion of Greece in 479 BC, the Persians eventually withdrew from their European territories, including from what is today North Macedonia.

Macedon and Rome

In 336 BC Philip II of Macedon fully annexed Upper Macedonia, including its northern part and southern Paeonia, which both now lie within North Macedonia.[11] Philip's son Alexander the Great conquered most of the remainder of the region, incorporating it in his empire, with exclusion of Dardania. The Romans included most of the Republic in their province of Macedonia, but the northernmost parts (Dardania) lay in Moesia; by the time of Diocletian, they had been subdivided, and the Republic was split between Macedonia Salutaris and Moesia prima.[12] Little is known about the Slavs before the 5th century CE.

Medieval period

Migration Period

At this period the area divided from the Jireček Line was populated from people of Thraco-Roman or Illyro-Roman origins, as well from Hellenized citizens of the Byzantine Empire and Byzantine Greeks. The ancient languages of the local Thraco-Illyrian people had already gone extinct before the arrival of the Slavs, and their cultural influence was highly reduced due to the repeated barbaric invasions on the Balkans during the early Middle Ages, accompanied by persistent hellenization, romanisation and later slavicisation. South Slavic tribes settled in the territory of present-day North Macedonia in the 6th century. The Slavic settlements were referred to by Byzantine Greek historians as "Sclavenes". The Sclavenes participated in several assaults against the Byzantine Empire – alone or aided by Bulgars or Avars. Around 680 AD the Bulgar group, led by khan Kuber (who belonged to the same Dulo clan as the Danubian Bulgarian Khan Asparukh), settled in the Pelagonian plain, and launched campaigns to the region of Thessaloniki.

In the late 7th century Justinian II organized massive expeditions against the Sklaviniai of the Greek peninsula, in which he reportedly captured over 110,000 Slavs and transferred them to Cappadocia. By the time of Constans II (who also organized campaigns against the Slavs), the significant number of the Slavs of Macedonia were captured and transferred to central Asia Minor where they were forced to recognize the authority of the Byzantine emperor and serve in its ranks.

Contested between various realms

.jpg.webp)

Use of the name "Sklavines" as a nation on its own was discontinued in Byzantine records after circa 836 as those Slavs in the Macedonia region became a population in the First Bulgarian Empire. Originally two distinct peoples, Sclavenes and Bulgars, the Bulgars assimilated the Slavic language/identity whilst maintaining the Bulgarian demonym and name of the empire. Slavic influence in the region strengthened along with the rise of this state, which incorporated the entire region to its domain in AD 837. Saints Cyril and Methodius, Byzantine Greeks born in Thessaloniki, were the creators of the first Slavic Glagolitic alphabet and Old Church Slavonic language. They were also apostles-Christianizators of the Slavic world. Their cultural heritage was acquired and developed in medieval Bulgaria, where after 885 the region of Ohrid became a significant ecclesiastical center. In conjunction with another disciple of Saints Cyril and Methodius, Saint Naum, he created a flourishing Bulgarian cultural center around Ohrid, where over 3,000 pupils were taught in the Glagolitic and Cyrillic script in what is now called Ohrid Literary School.

At the end of the 10th century, much of what is now North Macedonia became the political and cultural center of the First Bulgarian Empire under Tsar Samuel; while the Byzantine emperor Basil II came to rule the eastern part of the empire (what is now Bulgaria), including the then capital Preslav, in 972. A new capital was established at Ohrid, which also became the seat of the Bulgarian Patriarchate. From then on, the Bulgarian model became an integral part of wider Slavic culture as a whole. After several decades of almost incessant fighting, Bulgaria came under Byzantine rule in 1018. The whole of North Macedonia was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire as Theme of Bulgaria[13] and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was reduced in rank to an archbishopric, the Archbishopric of Ohrid.[14]

Dobromir Chrysos rebelled against the emperor and after an unsuccessful imperial campaign in autumn 1197, the emperor sued for peace and recognized Dobromir-Chrysus' rights to lands between the Strymon and Vardar, including Strumica and the fortress of Prosek.[15]

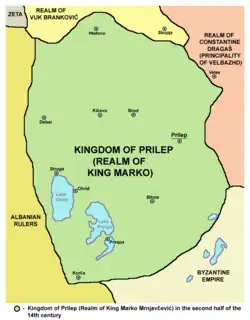

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Byzantine control was punctuated by periods of Bulgarian and Serbian rule. For example, Konstantin Asen – a former nobleman from Skopje – ruled as tsar of Bulgaria from 1257 to 1277. Later, Skopje became a capital of the Serbian Empire under Stefan Dušan. After the dissolution of the empire, the area became a domain of independent local Serbian rulers from the Mrnjavčević and Dragaš houses. The domain of the Mrnjavčević house included western parts of present-day North Macedonia and domains of the Dragaš house included eastern parts. The capital of the state of Mrnjavčević house was Prilep. There are only two known rulers from the Mrnjavčević house – king Vukašin Mrnjavčević and his son, king Marko. King Marko became a vassal of the Ottoman Empire and later died in the Battle of Rovine.

During the period in the 12th, 13th and early 14th century, parts of modern western North Macedonia were under the rule of the Albanian Noble Gropa family, which ruled territories between Ohrid and Debar. The city of Debar and some other territories after the ending rule of Gropa Noble family, were ruled by the Albanian Royal House of Kastrioti which ruled the Principality of Kastrioti during the end of the 14th century and the first half of the 15th century. After the death of the Albanian Prince Gjon Kastrioti in 1437, many parts of his domains were conquered by the Ottoman Empire and shortly after this, during the 15th century were again restored into the Albanian rule of League of Lezhë led by Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. During this period, western territories of modern North Macedonia became battleground between the Albanian and Ottoman armies. Some of the battles that took place in the territory of Macedonia were the Battle of Polog, Battle of Mokra, Battle of Ohrid, Battle of Otonetë, Battle of Oranik and many others. Skanderbeg's Campaign into Macedonia also took place. With the death of Skanderbeg on 17 January 1468 the Albanian Resistance began to fall. After the death of Skanderbeg the Albanian League was led by Lekë Dukagjini, but it did not have the same success as before and the last Albanian strongholds were conquered in 1479 in the Siege of Shkodër.

Ottoman period

Conquered by the Ottoman army at the end of the 14th century,[16] the region remained a part of the Ottoman Empire for over 500 years, as part of the province or Eyalet of Rumelia.[17] During this in the second half of the 15th century the Albanian Leader of the League of Lezhë, Skanderbeg was able to occupy places in modern western North Macedonia that were under Ottoman rule like the then well known city of Ohrid (Albanian Ohër) in the Battle of Ohrid.[18][19] Tetovo (Battle of Polog) and many other places. The Albanian forces under Skanderbeg penetrated deep into modern North Macedonia in the Battle of Mokra. But this did not last long and the places were again occupied by the Ottomans. Rumelia (Turkish: Rumeli) means "Land of the Romans" in Turkish, referring to the lands conquered by the Ottoman Turks from the Byzantine Empire.[20]). Over the centuries Rumelia Eyalet was reduced in size through administrative reforms, until by the nineteenth century it consisted of a region of central Albania and north-western part of the current state of North Macedonia with its capital at Manastir or present day Bitola.[21] Rumelia Eyalet was abolished in 1867 and the territory of North Macedonia subsequently became part of the provinces of Manastir Vilayet, Kosovo Vilayet and Salonica Vilayet until the end of Ottoman rule in 1912.

During the period of Ottoman rule the region gained a substantial Turkish minority, especially in the religious sense of Muslim; some of those Muslims became so through conversions. During the Ottoman rule, Skopje and Monastir (Bitola) were capitals of separate Ottoman provinces (eyalets). The valley of the river Vardar, which was later to become the central area of North Macedonia, was ruled by the Ottoman Empire prior to the First Balkan War of 1912, with the exception of the brief period in 1878 when it was liberated from Ottoman rule after the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), becoming part of Bulgaria. In 1903, a short-lived Kruševo Republic was proclaimed in the south-western part of present-day North Macedonia by the rebels of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising. Most of the ethnographers and travellers during Ottoman rule classified Slavic speaking people in Macedonia as Bulgarians. Examples include the 17th century traveller Evliya Çelebi in his Seyahatname: Book of Travels to the Ottoman census of Hilmi Pasha in 1904 and later. However, they also remarked that the language spoken in Macedonia had somewhat of a distinctive character — often described as a "Western Bulgarian dialect" as other Bulgarian dialects in modern western Bulgaria. Evidence also exists that certain Macedonian Slavs, particularly those in the northern regions, considered themselves as Serbs, on the other hand the intention to join Greece predominated in southern Macedonia where it was supported by substantial part of the Slavic-speaking population too. Although references are made referring to Slavs in Macedonia being identified as Bulgarians, some scholars suggest that ethnicity in medieval times was more fluid than what we see it to be today, an understanding derived from nineteenth century nationalistic ideals of a homogeneous nation-state.[22][23]

During the period of Bulgarian National Revival (1762–1878), many Bulgarians from Vardar Macedonia supported the struggle for creation of Bulgarian cultural educational and religious institutions, including the Bulgarian Exarchate. The subsequent Macedonian Struggle (1893–1908) remained inconclusive.

Karađorđević period (1912–1944)

Balkan Wars and World War I

The region was captured by the Kingdom of Serbia during First Balkan War of 1912 and was subsequently annexed to Serbia under the Karađorđević dynasty in the post-war peace treaties except Strumica region was part of Bulgaria between 1912 and 1919. It had no administrative autonomy and was called South Serbia (Južna Srbija) or "Old Serbia" (Stara Srbija). It was occupied by the Kingdom of Bulgaria between 1915 and 1918. After the First World War, the Kingdom of Serbia joined the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

Skopje after being captured by Albanian revolutionaries who defeated the Ottoman forces holding the city in August 1912.

Skopje after being captured by Albanian revolutionaries who defeated the Ottoman forces holding the city in August 1912..svg.png.webp) The Kingdom of Serbia in 1914, on the eve of World War I

The Kingdom of Serbia in 1914, on the eve of World War I Map showing Yugoslavia in 1919 in the aftermath of World War I before the treaties of Neuilly, Trianon and Rapallo[24]

Map showing Yugoslavia in 1919 in the aftermath of World War I before the treaties of Neuilly, Trianon and Rapallo[24] Provinces of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1920–1922

Provinces of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1920–1922

Royal Yugoslav period

After World War I (1914–1918) the Slavs in Serbian Macedonia ("Vardar Macedonia") were regarded as southern Serbs and the language they spoke a southern Serbian dialect. The Bulgarian, Greek and Romanian schools were closed, the Bulgarian priests and all non-Serbian teachers were expelled. The policy of Serbianization in the 1920s and 1930s clashed with pro-Bulgarian sentiment stirred by Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) detachments infiltrating from Bulgaria, whereas local communists favoured the path of self-determination.

In 1925, D. J. Footman, the British vice consul at Skopje, addressed a lengthy report for the Foreign Office. He wrote that "the majority of the inhabitants of Southern Serbia are Orthodox Christian Macedonians, ethnologically more akin to the Bulgarians than to the Serbs. He also pointed to the existence of the tendency to seek an independent Macedonia with Salonica as its capital."[25]

On 6 January 1929, king Alexander I Karađorđević committed a coup d'état and installed the so-called 6 January Dictatorship, abolishing the Vidovdan Constitution and renaming the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. It was divided into provinces called banovinas. The territory of Vardar Banovina had Skopje as its capital and it included what eventually became modern North Macedonia (plus some lands north of it that are now part of Serbia and Kosovo). Alexander's dictatorship effectively ruined parliamentary democracy, and after growing popular resentment against the king's autocratic rule, he was assassinated in 1934 in France by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).

World War II

During World War II, the Vardar Banovina was occupied between 1941 and 1944 by Italian-ruled Albania, which annexed the Albanian-populated western regions, and pro-German Bulgaria, which occupied the remainder. The occupying powers persecuted those inhabitants of the province who opposed the regime; this prompted some of them to join the Communist resistance movement of Josip Broz Tito. However, the Bulgarian army was well received by most of the population when it entered Macedonia[26] and it was able to recruit from the local population, which formed as much as 40% to 60% of the soldiers in certain battalions.

Socialist Yugoslav period

1944–1949

Following World War II, Yugoslavia was reconstituted as a federal state under the leadership of Tito's Yugoslav Communist Party. When the former Vardar province was established in 1944, most of its territory was transferred into a separate republic while the northernmost parts of the province remained with Serbia. In 1946, the new republic was granted federal status as an autonomous "People's Republic of Macedonia" within the new Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In the 1963 Constitution of Yugoslavia it was slightly renamed, to bring it in line with the other Yugoslav republics, as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia.

Greece was concerned by the initiatives of the Yugoslav government, as they were seen as a pretext for future territorial claims against the Greek region of Macedonia, which formed the bulk of historical Macedonia. The Yugoslav authorities also promoted the development of the Macedonians' ethnic identity and language. The Macedonian language was codified in 1944 (Keith 2003), from the Slavic dialect spoken around Veles. This further angered both Greece and Bulgaria, because of the possible territorial claims of the new states to the Greek and Bulgarian parts of the historic region of Macedonia received after the Balkan Wars.

During the Greek Civil War (1944–1949), many Macedonians (regardless of ethnicity) participated in the ELAS resistance movement organized by the Communist Party of Greece. ELAS and Yugoslavia were on good terms until 1949, when they split due to Tito's lack of allegiance to Joseph Stalin (cf. Cominform). After the end of the war, the ELAS fighters who took refuge in southern Yugoslavia and Bulgaria were not all permitted by Greece to return: only those who considered themselves Greeks were allowed, whereas those who considered themselves Bulgarian or Macedonian Slavs were barred. These events also contributed to the bad state of Yugoslav-Greek relations in the Macedonia region.

Independence

1990s

In 1990, the form of government peacefully changed from socialist state to parliamentary democracy. The first multi-party elections were held on 11 and 25 November and 9 December 1990.[27] After the collective presidency led by Vladimir Mitkov[28] was dissolved, Kiro Gligorov became the first democratically elected president of the Republic of Macedonia on 31 January 1991.[29] On 16 April 1991, the parliament adopted a constitutional amendment removing "Socialist" from the official name of the country, and on 7 June of the same year, the new name, "Republic of Macedonia", was officially established.

On 8 September 1991, the country held an independence referendum where 95.26% voted for independence from Yugoslavia, under the name of the Republic of Macedonia. The question of the referendum was formulated as "Would you support independent Macedonia with the right to enter future union of sovereign states of Yugoslavia?" (Macedonian: Дали сте за самостојна Македонија со право да стапи во иден сојуз на суверени држави на Југославија?). On 25 September 1991 the Declaration of Independence was formally adopted by the Macedonian Parliament making the Republic of Macedonia an independent country – although in Macedonia independence day is still celebrated as the day of the referendum 8 September. A new Constitution of the Republic of Macedonia was adopted on 17 November 1991.

Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, the position of ethnic Albanians was uncertain in the early years of the new Macedonian republic. Various Albanian political parties emerged, of which the Party for Democratic Prosperity (PDP) was the largest and most prominent. The PDP called for the improvement of the status of Albanians in North Macedonia, such as extended education rights and Albanian language usage, constitutional changes, release of political prisoners, proportional voting system and an end to discrimination. Discontent with the lack of constitutional recognition of collective rights for Albanians resulted in PDP leader Nevzat Halili declaring his party would regard the constitution as invalid and move toward seeking autonomy, declaring a Republic of Ilirida in 1992 and again in 2014. The proposal has been declared unconstitutional by the Macedonian government.

Bulgaria was the first country to recognize the new Macedonian state under its constitutional name. However, international recognition of the new country was delayed by Greece's objection to the use of what it considered a Hellenic name and national symbols, as well as controversial clauses in the Republic's constitution, a controversy known as the Macedonia naming dispute. To compromise, the country was admitted to the United Nations under the provisional name of "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" on 8 April 1993.[30]

Greece was still dissatisfied and it imposed a trade blockade in February 1994. The sanctions were lifted in September 1995 after Macedonia changed its flag and aspects of its constitution that were perceived as granting it the right to intervene in the affairs of other countries. The two neighbours immediately went ahead with normalizing their relations, but the state's name remains a source of local and international controversy. The usage of each name remains controversial to supporters of the other.

After the state was admitted to the United Nations under the temporary reference "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", other international organisations adopted the same convention. More than half of the UN's member states have recognized the country as the Republic of Macedonia, including the United States of America while the rest use the temporary reference "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" or have not established any diplomatic relations with the country.

In 1999, the Kosovo War led to 340,000 Albanian refugees from Kosovo fleeing into the Republic of Macedonia, greatly disrupting normal life in the region and threatening to upset the balance between Macedonians and Albanians. Refugee camps were set up in the country. Athens did not interfere with the Republic's affairs when NATO forces moved to and from the region ahead a possible invasion of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Thessaloniki was the main depot for humanitarian aid to the region. The Republic of Macedonia did not become involved in the conflict.

In end the war, Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević reached an agreement with NATO which allowed refugees to return under UN protection. However, the war increased tensions, and relations between Macedonians and the Albanian minority became strained. On the positive side, Athens and Ankara presented a united front of 'non-involvement'. In Greece, there was a strong reaction against NATO and the United States.

2000s

In the spring of 2001, ethnic Albanian insurgents calling themselves the National Liberation Army (some of whom were former members of the Kosovo Liberation Army) took up arms in the north and northwest of the Republic of Macedonia. They demanded that the constitution be rewritten to enshrine certain Albanian minority interests such as language rights. The guerillas received support from Albanians in NATO-controlled Kosovo and Albanian guerrillas in the demilitarized zone between Kosovo and the rest of Serbia. The fighting was concentrated in and around Tetovo, the fifth largest city in the country, and in the wider regions of Skopje, the capital, and Kumanovo, the third largest city.

After a joint NATO-Serb crackdown on Albanian guerrillas in Kosovo, European Union (EU) officials were able to negotiate a cease-fire in June. The government would give to the citizens of Albanian descent greater civil rights, and the guerrilla groups would voluntarily relinquish their weapons to NATO monitors. This agreement was a success, and in August 2001 3,500 NATO soldiers conducted "Operations Essential Harvest" to retrieve the arms. Directly after the operation finished in September the NLA officially dissolved itself. Ethnic relations have since improved significantly, although hardliners on both sides have been a continued cause for concern and some low level violence continues particularly directed against police.

On 26 February 2004, President Boris Trajkovski died in a plane crash near Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The results of the official investigation revealed that the cause of the plane accident was procedural mistakes by the crew, committed during the approach to land at Mostar Airport.

In March 2004, the country submitted an application for membership of the European Union, and on 17 December 2005 was listed by the EU Presidency conclusions as an accession candidate (as "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia"). However, accession proceedings were delayed due to opposition by Greece until the 2018 resolution of the Macedonia naming dispute, and later by Bulgaria due to unresolved differences between the two countries on the history of the region and what is perceived as "anti-Bulgarian ideology".[31][32]

2010s–2020s

_(42853677381).jpg.webp)

In June 2017, Zoran Zaev of Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) became new Prime Minister six months after early elections. The new center-left government ended 11 years of conservative VMRO-DPMNE rule led by former Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski.[33]

In June 2018, the Prespa agreement was reached between the governments of Greece and the then-Republic of Macedonia to rename the latter the Republic of North Macedonia, or North Macedonia for short. This agreement, after it had been accepted by the respective legislatures of both countries, came into effect on 12 February 2019, thus ending the disputes.[34]

Stevo Pendarovski (SDSM) was sworn in as North Macedonia's new president in May 2019.[35] The early parliamentary elections took place on 15 July 2020.[36] Zoran Zaev has served as the Prime Minister of the Republic of North Macedonia again since August 2020.[37] Prime Minister Zoran Zaev announced his resignation after his party, the Social Democratic Union, suffered losses in local elections in October 2021.[38] After internal party leadership elections, Dimitar Kovačevski succeeded him as leader of the SDSM on 12 December 2021,[39] and was sworn in as Prime Minister of North Macedonia on 16 January 2022, securing a 62–46 confidence vote in Parliament for his new SDSM-led coalition cabinet.[40]

See also

- Breakup of Yugoslavia

- History of Albania

- History of the Balkans

- History of Bulgaria

- History of Europe

- History of Greece

- History of Kosovo

- History of Serbia

- History of Turkey

- History of Yugoslavia

- Macedonia (region)

- Macedonian nationalism

- United Macedonia

- Military history of North Macedonia

- Independent State of Macedonia

- League of Communists of Yugoslavia

- President of the Republic of North Macedonia

- List of prime ministers of North Macedonia

- List of presidents of Yugoslavia

- List of prime ministers of Yugoslavia

- Politics of North Macedonia

References

- Georgieva, Valentina (1998). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3336-0.

- Brown, Keith (2003). The Past in Question : Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- Dalibor Jovanovski, "Greek Historiography and the Balkan Wars", On Macedonian Matters. From the partition and annexation of Macedonia in 1913 to the present (Verlag Otto Sagner: Munich, Berlin, 2015). http://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/38056455/dalibor_statija.pdf [archive]

Notes

- Bauer, Susan Wise: The History of the Ancient World: From the Earliest Accounts to the Fall of Rome (2007), ISBN 0-393-05974-X, page 518: "... Italy); to the north, Thracian tribes known collectively as the Paeonians."

- Wilkes, John: The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, p. 49.

- Sealey, Raphael, A history of the Greek city states, ca. 700-338 B.C., p. 442. University of California Press, 1976. ISBN 0-520-03177-6.

- Evans, Thammy, Macedonia, Bradt Travel Guides, 2007, ISBN 1-84162-186-2, p. 13

- Borza, Eugene N., In the shadow of Olympus: the emergence of Macedon, Princeton University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-691-00880-9, pp. 74-75.

- Lewis, D.M. et al. (ed.), The Cambridge ancient history: The fourth century B.C., Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-23348-8, pp. 723-724.

- The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 3, Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries BC by John Boardman and N. G. L. Hammond, 1982, ISBN 0-521-23447-6, page 284

- Timothy Howe, Jeanne Reames. "Macedonian Legacies: Studies in Ancient Macedonian History and Culture in Honor of Eugene N. Borza" Regina Books, 2008, Originally from the Indiana University. Digitalised 3 November 2010 ISBN 9781930053564. p. 239

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (7 July 2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. ISBN 9781444351637. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Persian influence on Greece (2)". Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Poulton, Hugh, Who are the Macedonians? C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1-85065-534-0, p. 14.

- Encyclopædia Britannica — Scopje

- "Archived copy". img53.exs.cx. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - http://assets.cambridge.org/97805217/70170/excerpt/9780521770170_excerpt.pdf

- Paul Stephenson, Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900-1204, Cambridge University Press, 29 iun. 2000, p.307

- Michael Palairet, Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2, From the Fifteenth Century to the Present), Vol. 2; Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016, ISBN 1443888494, p. 2.

- "North Macedonia | History, Geography, & Points of Interest". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Skënderbeu dhe lufta shqiptaro-turke në shek. XV. Frashëri, Kristo., Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë. Tiranë: Botimet Toena. 2005. ISBN 99943-1-042-9. OCLC 70911640.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Frashëri, Kristo; Frashëri, Gjergj; Dhamo, Dhorka; Kuqali, Andon; Dashi, Sulejman (2003), "Albania", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t001473

- Encyclopædia Britannica – Rumelia at Encyclopædia Britannica.com

- The Encyclopædia Britannica, or, Dictionary of arts, sciences ..., Volume 19. 1859. p. 464.

- Walter Pohl. (p. 13-24 in: Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings, Ed. Lester K. Little and Barbara H. Rosenwein, Blackwell Publishers, 1998)Ethnic boundaries are not static, and even less so in a period of migrations. It is possible to change one's ethnicity... Even more frequently, in the Early Middle Ages, people lived under circumstances of ethnic ambiguity.

- John V A Fine. When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11414-X. Pg 3 most South Slavs mentioned with specific national-type names mentioned in our sources were such by political affiliation, namely that the individuals named so served the given state's ruler, and cannot be considered ethnic Serbs, Croats or whatever

- Note that this map does not reflect any internationally established borders or armistice lines – it only reflect opinion of the researchers from London Geographical Institute about issue how final borders should look after the Paris Peace Conference.

- The British Foreign Office and Macedonian National Identity, 1918-1941, Andrew Rossos' Slavic Review, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer, 1994), pp. 369-394

- Marshall Lee Miller, Bulgaria During the Second World War, Stanford University Press, 1975, p.123

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Faculty of Law, University of Skopje Archived 30 June 2012 at archive.today (in Macedonian)

- Kiro Gligorov was elected president on 31 January 1991, when SR Macedonia was still an official name of the nation. After the change of the state's name, he continued his function as a President of the Republic of Macedonia – The Official Site of The President of the Republic of Macedonia Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "A/RES/47/225. Admission of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to membership in the United Nations". Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- Marusic, Sinisa Jakov (10 October 2019). "Bulgaria Sets Tough Terms for North Macedonia's EU Progress Skopje". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019.

- "Bulgaria sends memorandum to the Council on North Macedonia". Radio Bulgaria. 17 September 2020.

- "Macedonia gets new government six months after elections | DW | 01.06.2017". Deutsche Welle.

- "North Macedonia name change enters force | DW | 12.02.2019". Deutsche Welle.

- "North Macedonia's new president Stevo Pendarovski takes office". 12 May 2019.

- "EM North Macedonia: Review of the 2020 parliamentary elections in North Macedonia".

- "President of the Government of the Republic of North Macedonia – Zoran Zaev". 11 May 2018.

- "North Macedonia Prime Minister Zoran Zaev resigns | DW | 31.10.2021". Deutsche Welle.

- "North Macedonia Ruling Party Elects Dimitar Kovacevski as Leader". Balkan Insight. 13 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- "North Macedonia's Lawmakers Elect Dimitar Kovacevski As New PM". Radio Free Europe. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

Further reading

- Mattioli, Fabio (2020). Dark Finance: Illiquidity and Authoritarianism at the Margins of Europe. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-1294-5.

External links

- The Mariovo in Macedonia, 1564: Mariovo People and Macedonia.

- New Power – Federated Yugoslavia

- History of Macedonia: Primary Documents

- Discover Macedonia – Discover North Macedonia on Facebook