Byzantine Greece

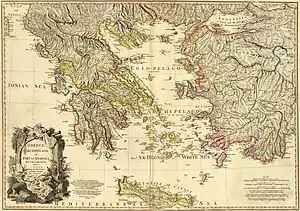

Byzantine Greece has a history that mainly coincides with that of the Byzantine Empire itself.

| History of Greece |

|---|

|

|

|

Background: Roman Greece

The Greek peninsula became a Roman protectorate in 146 BC, and the Aegean islands were added to this territory in 133 BC. Athens and other Greek cities revolted in 88 BC, and the peninsula was crushed by the Roman general Sulla. The Roman civil wars devastated the land even further, until Augustus organized the peninsula as the province of Achaea in 27 BC.

Greece was a typical eastern province of the Roman Empire. The Romans sent colonists there and contributed new buildings to its cities, especially in the Agora of Athens, where the Agrippeia of Marcus Agrippa, the Library of Titus Flavius Pantaenus, and the Tower of the Winds, among others, were built. Romans tended to be philhellenic and Greeks were generally loyal to Rome.

Life in Greece continued under the Roman Empire much the same as it had previously, and Greek continued to be the lingua franca in the Eastern and most important part of the Empire. Roman culture was heavily influenced by classical Greek culture (see Greco-Roman) as Horace said, Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit (Translation: "Captive Greece took captive her rude conqueror"). The epics of Homer inspired the Aeneid of Virgil, and authors such as Seneca the Younger wrote using Greek styles, while famous Romans such as Scipio Africanus, Julius Caesar and Marcus Aurelius compiled works in the Greek language.

During that period, Greek intellectuals such as Galen or Apollodorus of Damascus were continuously being brought to Rome. Within the city of Rome, Greek was spoken by Roman elites, particularly philosophers, and by lower, working classes such as sailors and merchants. The emperor Nero visited Greece in 66, and performed at the Olympic Games, despite the rules against non-Greek participation. He was, of course, honored with a victory in every contest, and in 67 he proclaimed the freedom of the Greeks at the Isthmian Games in Corinth, just as Flamininus had over 200 years previously.

Hadrian was also particularly fond of the Greeks; before he became emperor he served as eponymous archon of Athens. He also built his namesake arch there, and had a Greek lover, Antinous.

At the same time, Greece and much of the rest of the Roman east came under the influence of Christianity. The apostle Paul had preached in Corinth and Athens, and Greece soon became one of the most highly Christianized areas of the empire.

Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire (4th century)

During the second and third centuries, Greece was divided into provinces including Achaea, Macedonia, Epirus vetus and Thracia. During the reign of Diocletian in the late 3rd century, the western Balkans were organized as a Roman diocese, and was ruled by Galerius. Under Constantine I Greece was part of the dioceses of Macedonia and Thrace. The eastern and southern Aegean islands formed the province of Insulae in the Diocese of Asia.

Greece faced invasions from the Heruli, Goths, and Vandals during the reign of Theodosius I. Stilicho, who acted as regent for Arcadius, evacuated Thessaly when the Visigoths invaded in the late 4th century. Arcadius' Chamberlain Eutropius allowed Alaric to enter Greece, and he looted Corinth, and the Peloponnese. Stilicho eventually drove him out around 397 and Alaric was made magister militum in Illyricum. Eventually, Alaric and the Goths migrated to Italy, sacked Rome in 410, and built the Visigothic Empire in Iberia and southern France, which lasted until 711 with the advent of the Arabs.

Greece remained part of the relatively unified eastern half of the empire. Contrary to outdated visions of late antiquity, the Greek peninsula was most likely one of the most prosperous regions of the Roman and later the Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire. Older scenarios of poverty, depopulation, barbarian destruction and civil decay have been revised in light of recent archaeological discoveries.[1] In fact, the polis, as an institution, appears to have remained prosperous until at least the sixth century. Contemporary texts such as Hierocles' Synecdemus affirm that in late Antiquity, Greece was highly urbanised and contained approximately 80 cities.[1] This view of extreme prosperity is widely accepted today, and it is assumed between the 4th and 7th centuries AD, Greece may have been one of the most economically active regions in the eastern Mediterranean.[1]

Following the loss of Alexandria and Antioch to the Arabs, Thessaloniki became the Byzantine Empire's second largest city, called the "co-regent" (symbasileuousa), second only to Constantinople. The Greek peninsula remained one of the strongest centers of Christianity in the late Roman and early Byzantine periods. After the area's recovery from the Slavic invasions, its wealth was restored. Events such as the Seljuk invasion of Asia Minor and the Latin occupation of Constantinople gradually focused Byzantine imperial interest to the Greek peninsula during the late Byzantine period. The Peloponnese in particular continued to prosper economically and intellectually even during its Latin domination, the Byzantine recovery, and until its final fall to the Ottoman Empire.

Further invasions and reorganization (5th–8th centuries)

.jpg.webp)

Greece was raided in Macedonia in 479 and 482 by the Ostrogoths under their king, Theodoric the Great (493–526).[2] The Bulgars also raided Thrace and the rest of northern Greece in 540 and on repeated other occasions. These continuing Bulgar invasions required the Byzantine Empire to build a defensive wall, called the "Anastasian Wall," that extended for some thirty (30) miles, or more, from the city of Selymbria (now Silivri) to the Black Sea.[3] The Huns and Bulgars raided Greece in 559 until the Byzantine army returned from Italy, where Justinian I had been attempting to capture the heart of the Roman Empire.[4]

According to historical documents, the Slavs invaded and settled in parts of Greece beginning in 579 and Byzantium nearly lost control of the entire peninsula during the 580s.[5] However, there is no archaeological evidence indicating Slavic penetration of imperial Byzantine territories before the end of the 6th century. Overall, traces of Slavic culture in Greece are very rare.[6]

The city of Thessaloniki remained unconquered even after being attacked by the Slavs around 615. The Slavs were eventually defeated, gathered by the Byzantines and placed into segregated communities known as Sclaviniae.

In 610, Heraclius became Emperor. During his reign, Greek became the official language of the empire.

During the early 7th century, Constans II made the first mass-expulsions of Slavs from the Greek peninsula to the Balkans and central Asia Minor. Justinian II defeated and destroyed most of the Sclaviniae, and moved as many as 100–200,000 Slavs from the Greek peninsula to Bithynia, while he enlisted some 30,000 Slavs in his army.[7]

The Slavic populations that were placed in these segregated communities were used for military campaigns against the enemies of the Byzantines. In the Peloponnese, more Slavic invaders brought disorder to the western part of the peninsula, while the eastern part remained firmly under Byzantine domination. Empress Irene organised a military campaign which liberated those territories and restored Byzantine rule to the region, but it was not until emperor Nicephorus I's reign that the last trace of Slavic element was eliminated:[8] when the Slavs first occupied the Peloponnese in the 6th century, a number Greeks had fled Patras and found refuge near Reggio Calabria, in southern Italy; the descendants of these refugees were ordered to return by Nicephorus, who resettled them in the Peloponnese.[9]

In the mid-7th century, the empire was reorganized into "themes" by the Emperor Constans II, including the Theme of Thrace, the naval Karabisianoi corps in southern Greece and the Aegean islands. The Karabisanoi were later divided by Justinian II into the Theme of Hellas (centred on Corinth) and the Cibyrrhaeotic Theme. By this time, the Slavs were no longer a threat to the Byzantines since they had been either defeated numerous times or placed in the Sclaviniae. The Slavic communities in Bithynia were destroyed by the Byzantines after General Leontios lost to the Arabs in the Battle of Sebastopolis in 692, as a result of the Slavs having defected to the Arab side.[10]

These themes rebelled against the iconoclast emperor Leo III in 727 and attempted to set up their own emperor, although Leo defeated them. Leo then moved the headquarters of the Karabisianoi to Anatolia and created the Cibyrrhaeotic Theme of them. Up to this time, Greece and the Aegean were still technically under the ecclesiastic authority of the Pope, but Leo also quarreled with the Papacy and gave these territories to the Patriarch of Constantinople. As emperor, Leo III, introduced more administrative and legal reforms than had been promulgated since the time of Justinian.[11] Meanwhile, the Arabs began their first serious raids in the Aegean. Bithynia was eventually re-populated by Greek-speaking population from mainland Greece and Cyprus.

Bulgarian and Arab threats and Byzantine victory (8th–11th centuries)

Nicephorus I also began to reconquer Slavic and Bulgar-held areas in the early 9th century.[12] He resettled Greek-speaking families from Asia Minor to the Greek peninsula and the Balkans, and expanded the theme of Hellas to the north to include parts of Thessaly and Macedonia, and to the south to include the regained territory of the Peloponnese. Thessalonica, previously organized as an archontate surrounded by the Slavs, became a theme of its own as well. These themes contributed another 10,000 men to the army, and allowed Nicephorus to convert most of the Slavs to Christianity.

Crete was conquered by the Arabs in 824. In the late 9th century, Leo VI faced also invasions from the Bulgarians under Simeon I, who pillaged Thrace in 896, and again in 919 during Zoe's regency for Constantine VII. Simeon invaded northern Greece again in 922 and penetrated deep to the south seizing Thebes, just north of Athens.

Crete was reconquered in 961 from the Arabs, by Nikephoros II Phokas after the Siege of Chandax.

In the late 10th century, the greatest threat to Greece was from Samuel, who constantly fought over the area with Basil II. In 985, Samuel captured Thessaly and the important city of Larissa, and in 989, he pillaged Thessalonica. Basil slowly began to recapture these areas in 991, but Samuel captured the areas around Thessalonica and the Peloponnese again in 997 before being forced to withdraw to Bulgaria. In 999, Samuel captured Dyrrhachium and raided northern Greece once more. Basil recaptured these areas by 1002 and had fully subjugated completely the Bulgarians in the decade before his death (see Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria).

By Basil's death in 1025, Greece was divided into themes including Crete, the Peloponnese, Thrace, Hellas, Nicopolis, Larissa, Cephalonia, Thessalonica and Strymon, the Cyclades and the Aegean Sea. They were protected from raids and invasions by the new themes created out of Bulgar territory.

Greece became more prosperous in the 10th century and towns and cities began to grow again. Athens and Corinth probably grew to about 10,000 people, while Thessalonica may have had as many as 100,000 people. There was an important aristocratic class from these themes, especially the Macedonian emperors who ruled the empire from 867 to 1056.

Normans and Franks

Greece and the empire as a whole faced a new threat from the Normans of Sicily in the late 11th century. Robert Guiscard took Dyrrhachium and Corcyra in 1081 (see Battle of Dyrrhachium), but Alexius I defeated him, and later his son Bohemund, by 1083. The Pechenegs also raided Thrace during this period.

In 1147, while the knights of the Second Crusade made their way through Byzantine territory, Roger II of Sicily captured Corcyra and pillaged Thebes and Corinth.

In 1197, Henry VI of Germany continued his father Frederick Barbarossa's antagonism towards the empire by threatening to invade Greece to reclaim the territory the Normans had briefly held. Alexius III was forced to pay him off, although the taxes he imposed caused frequent revolts against him, including rebellions in Greece and the Peloponnese. Also during his reign, the Fourth Crusade attempted to place Alexius IV on the throne, until it eventually invaded and sacked the capital.

Greece was relatively peaceful and prosperous in the 11th and 12th centuries, compared to Anatolia which was being overrun by the Seljuks. Thessalonica had probably grown to about 150,000 people, despite being looted by the Normans in 1185. Thebes also became a major city with perhaps 30,000 people, and was the centre of a major silk industry. Athens and Corinth probably still had around 10,000 people. Mainland Greek cities continued to export grain to the capital in order to make up for the land lost to the Seljuks.

However, after Constantinople was conquered during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, Greece was divided among the Crusaders. The Latin Empire held Constantinople and Thrace, while Greece itself was divided into the Kingdom of Thessalonica, the Principality of Achaea, and the Duchy of Athens. The Venetians controlled the Duchy of the Archipelago in the Aegean, while the Despotate of Epirus was established as one of the three Byzantine Greek successor states.

Michael VIII restored the empire in 1261, having also regained the Kingdom of Thessalonica. By his death in 1282, Michael had taken back the Aegean islands, Thessaly, Epirus, and most of Achaea, including the Crusader fortress of Mystras, which became the seat of a Byzantine despotate. However, Athens and the northern Peloponnese remained in Crusader hands. Charles of Anjou and later his son claimed the throne of the defunct Latin Empire, and threatened Epirus and Greece, but were never able to make any progress there.

Ottoman threat and conquest

By the reign of Andronicus III Palaeologus, beginning in 1328, the empire controlled most of Greece, especially the metropolis of Thessalonica, but very little else. Epirus was nominally Byzantine but still occasionally rebelled, until it was fully recovered in 1339. Greece was mostly used as a battleground during the civil war between John V Palaeologus and John VI Cantacuzenus in the 1340s, and at the same time the Serbs and Ottomans began attacking Greece as well. By 1356, another independent despotate was set up in Epirus and Thessaly.

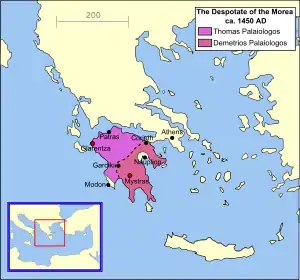

The Peloponnese, usually called Morea in this period, was now almost the centre of the empire, and was certainly the most fertile area. Mystras and Monemvasia were populous and prosperous, even after the Black Plague in the mid-14th century. Mystras rivaled Constantinople in importance. It was a stronghold of Greek Orthodoxy and bitterly opposed attempts by the emperors to unite with the Catholic Church, even though this would have allowed the empire to gain help from the west against the Ottomans.

The Ottomans had begun their conquest of the Balkans and Greece in the late 14th century and early 15th century capturing among others Thessaloniki, Ioannina and Thessaly. In 1445, Ottoman-occupied Thessaly was recaptured by the future emperor Constantine XI, at the time despot of Mystras, but there was little he could do against most of the other Ottoman territories. Emperor Constantine XI was defeated and killed in 1453 when the Ottomans finally captured Constantinople. After the fall of Constantinople, the Ottomans also captured Athens by 1458, but left a Byzantine despotate in the Peloponnese until 1460. The Venetians still controlled Crete, Aegean islands and some cities-ports, but otherwise the Ottomans controlled many regions of Greece except the mountains and heavily forested areas.

Gallery

Kapnikarea church, Athens

Kapnikarea church, Athens View of Hosios Loukas monastery, an example of Byzantine architecture during the Macedonian Renaissance

View of Hosios Loukas monastery, an example of Byzantine architecture during the Macedonian Renaissance Mosaics of Nea Moni of Chios

Mosaics of Nea Moni of Chios

Despotate of the Morea (1349–1460)

Despotate of the Morea (1349–1460) The Byzantine Castle of Angelokastro (Corfu) successfully repulsed the Ottomans

The Byzantine Castle of Angelokastro (Corfu) successfully repulsed the Ottomans

See also

References

- Rothaus, p. 10. "The question of the continuity of civic institutions and the nature of the polis in the late antique and early Byzantine world have become a vexed question, for a variety of reasons. Students of this subject continue to contend with scholars of earlier periods who adhere to a much-outdated vision of late antiquity as a decadent decline into impoverished fragmentation. The cities of late-antique Greece displayed a marked degree of continuity. Scenarios of barbarian destruction, civic decay, and manorialization simply do not fit. In fact, the city as an institution appears to have prospered in Greece during this period. It was not until the end of the 6th century (and maybe not even then) that the dissolution of the city became a problem in Greece. If the early sixth-century Synecdemus of Hierocles is taken at face value, late-antique Greece was highly urbanized and contained approximately eighty cities. This extreme prosperity is borne out by recent archaeological surveys in the Aegean. For late-antique Greece, a paradigm of prosperity and transformation is more accurate and useful than a paradigm of decline and fall."

- John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries (Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 1996)

- John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, p. 187.

- Robert S. Hoyt & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages (Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, Inc.: New York, 1976) p. 76.

- John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: the Early Centuries, p. 260.

- "Slavs." Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Volume 3, pp. 1916-1919.

- John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, p. 329.

- Curta, Florin. Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Publisher:Historical Publications St. D. Basilopoulos, Athens, 1987. ISBN 0-521-81539-8

- Niavis, Pavlos. The Reign of the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus I. (AD 802-811). Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Years, pp. 330-331

- Robert S. Hoyt & Stanley Chodorow, Europe in the Middle Ages

- John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The early Centuries, p. 342.

Bibliography

- Avramea, Anna (2012). Η Πελοπόννησος από τον 4ο ως τον 8ο αιώνα: Αλλαγές και συνέχεια [The Peloponnese from the 4th to the 8th century: Changes and continuity.] (in Greek). Athens: National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation. ISBN 978-960-250-501-4.

- Bon, Antoine (1951). Le Péloponnèse byzantin jusqu'en 1204 (in French). Presses Universitaires de France.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- Curta, Florin (2011). The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, c. 500 to 1050: The Early Middle Ages. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3809-3.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453 (Second ed.). London: Rupert Hart-Davis Ltd. ISBN 0-246-10559-3.

- Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (2010). The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13089-9.

- Rothaus, Richard M. Corinth: The First City of Greece. Brill, 2000. ISBN 90-04-10372-4

- Dimov, G. The Notion of the Byzantine City in the Balkans and in Southern Italy - 11th and 12th Centuries - В: Realia Byzantino-Balcanica. Сборник в чест на 60 годишнината на професор Христо Матанов. София, 2014.