Kingdom of Asturias

Kingdom of Asturias | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 718[1]–924 | |||||||||||

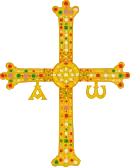

Cruz de la Victoria, the jewelled cross as a pre-heraldic symbol

| |||||||||||

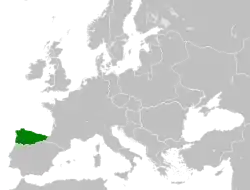

Location of the Kingdom of Asturias in 814 AD | |||||||||||

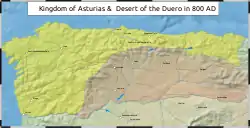

The Kingdom of Asturias c. 800 AD | |||||||||||

| Capital | Cangas de Onís, San Martín del Rey Aurelio, Pravia, Oviedo | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Latin, Vulgar Latin (Astur-Leonese, Castilian, Galician-Portuguese), East Germanic varieties (minority speakers of Visigothic and Vandalic) | ||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity (official)[2] | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute elective monarchy (until 842) Absolute hereditary monarchy (from 842) | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 718–737 | Pelagius of Asturias | ||||||||||

• 910–924 | Fruela II of Asturias | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early Middle Ages | ||||||||||

| 718[3] | |||||||||||

• Monarchy becomes hereditary | 842 | ||||||||||

| 910 | |||||||||||

• Incorporated into the Kingdom of León | 924 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Spain Portugal | ||||||||||

| History of Spain |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| History of Portugal |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Kingdom of Asturias (Latin: Asturum Regnum; Asturian: Reinu d'Asturies) was a kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula founded by the Visigothic nobleman Pelagius. It was the first Christian political entity established after the Umayyad conquest of Visigothic Hispania in 718.[4] That year, Pelagius defeated an Umayyad army at the Battle of Covadonga, in what is usually regarded as the beginning of the Reconquista.

The Asturian kings would occasionally make peace with the Muslims, particularly at times when they needed to pursue their other enemies, the Basques and rebels in Galicia. Thus Fruela I (757–768) fought Muslims but also defeated the Basques and Galicians,[5] and Silo (774–783) made peace with the Muslims but not with the Galicians. Under King Alfonso II (791–842), the kingdom was firmly established with Alfonso's recognition as king of Asturias by Charlemagne and the Pope. He conquered Galicia and the Basques. During his reign, the holy bones of St James the Great were declared to be found in Galicia, in Compostela (from Latin campus stellae, literally "the field of the star"). Pilgrims from all over Europe opened a way of communication between the isolated Asturias and the Carolingian lands and beyond. Alfonso's policy consisted in depopulating the borders of Bardulia (which would turn into Castile) in order to gain population support north of the mountains. With this growth came a corresponding increase in military forces. The kingdom was now strong enough to sack the Moorish cities of Lisbon, Zamora and Coimbra. However, for centuries to come the focus of these actions was not conquest but pillage and tribute. In the summers of 792, 793 and 794 several Muslim attacks plundered Alava, and the heart of the Asturian kingdom, reaching up to the capital, Oviedo. In one of the retreats, Alfonso inflicted a severe defeat on the Muslims in the swampy area of Lutos.[6]

When Alfonso II died, Ramiro I (842–50) staged a coup against the Count of the Palace Nepotian, who had taken the throne. After a battle on a bridge over the river Narcea, Nepotian was captured in flight, blinded and then forced into monastic life. Early in his reign, in 844, Ramiro was faced with a Viking attack at a place called Farum Brecantium, believed to be present-day Corunna. He gathered an army in Galicia and Asturias and defeated the Vikings, killing many of them and burning their ships.[7][8] In 859, a second Viking fleet set out for Spain. The Vikings were slaughtered off the coast of Galicia by Count Pedro.[9] The considerable territorial expansion of the Asturian kingdom under Alfonso III (866–910) was largely made possible by the collapse of Umayyad control over many parts of Al-Andalus at this time. Between in the year 773[10] the western frontier of the kingdom in Galicia was expanded into the northern part of modern-day Portugal pushing the border roughly to the Douro valley, and between 868 and 881 it expanded further south reaching all the way to the Mondego. The year 878 saw a Muslim assault on the towns of Astorga and León. The expedition consisted of two detachments, one of which was decisively defeated at Polvoraria on the river Órbigo, with an alleged loss of 13,000 men. In 881, Alfonso took the offensive, leading an army deep into the Lower March, crossing the Tagus River to approach Mérida. Then miles from the city the Asturian army crossed the Guadiana River and defeated the Umayyad army on "Monte Oxifer", allegedly leaving 15,000 Muslim soldiers killed. Returning home, Alfonso devoted himself to building the churches of Oviedo and constructing one or two more palaces for himself.

The Kingdom of Asturias transitioned into the Kingdom of León in 925, when Fruela II of Asturias became king with his royal court in León.[11]

Indigenous background

The kingdom originated in the western and central territory of the Cantabrian Mountains, particularly the Picos de Europa and the central area of Asturias. The main political and military events during the first decades of the kingdom's existence took place in the region. According to the descriptions of Strabo, Cassius Dio and other Graeco-Roman geographers, several peoples of Celtic origin inhabited the lands of Asturias at the beginning of the Christian era, most notably:

- in the Cantabri, the Vadinienses, who inhabited the Picos de Europa region and whose settlement gradually expanded southward during the first centuries of the modern era

- the Orgenomesci, who dwelled along the Asturian eastern coast

- in the Astures, the Saelini, whose settlement extended through the Sella Valley

- the Luggones, who had their capital in Lucus Asturum and whose territories stretched between the Sella and Nalón

- the Astures (in the strictest sense), who dwelled in inner Asturias, between the current councils of Piloña and Cangas del Narcea

- the Paesici, who had settled along the coast of Western Asturias, between the mouth of the Navia river and the modern city of Gijón

Classical geographers give conflicting views of the ethnic description of the above-mentioned peoples. Ptolemy says that the Astures extended along the central area of current Asturias, between the Navia and Sella rivers, fixing the latter river as the boundary with the Cantabrian territory. However, other geographers placed the frontier between the Astures and the Cantabri further to the east: Julius Honorius stated in his Cosmographia that the springs of the river Ebro were located in the land of the Astures (sub asturibus). In any case, ethnic borders in the Cantabrian Mountains were not so important after that time, as the clan divisions that permeated the pre-Roman societies of all the peoples of Northern Iberia faded under similar political administrative culture imposed on them by the Romans.

The situation started to change during the Late Roman Empire and the early Middle Ages, when an Asturian identity gradually started to develop: the centuries-old fight between Visigothic and Suebian nobles may have helped to forge a distinct identity among the peoples of the Cantabrian districts. Several archaeological digs in the castro of La Carisa (municipality of Lena) have found remnants of a defensive line whose main purpose was to protect the valleys of central Asturias from invaders who came from the Meseta through the Pajares pass: the construction of these fortifications reveals a high degree of organization and cooperation among the several Asturian communities, in order to defend themselves from the southern invaders. Carbon-14 tests have found that the wall dates from the period 675–725 AD, when two armed expeditions against the Asturians took place: one of them headed by Visigothic king Wamba (reigned 672–680); the other by Muslim governor Musa bin Nusayr during the Umayyad conquest, who settled garrisons over its territory.

The gradual formation of Asturian identity led to the creation of the Kingdom of Asturias after Pelagius' coronation and the victory over the Muslim garrisons in Covadonga in the early 8th century. The Chronica Albeldense, in narrating the happenings of Covadonga, stated that "Divine providence brings forth the King of Asturias".

Umayyad occupation and Asturian revolt

The kingdom was established by the nobleman Pelayo (Latin: Pelagius), possibly an Asturian noble. No substantial movement of refugees from central Iberia could have taken place before the Battle of Covadonga, and in 714 Asturias was overrun by Musa bin Nusayr with no effective or known opposition.[12] It has also been claimed that he may have retired to the Asturian mountains after the Battle of Guadalete, where in the Gothic tradition of Theias he was elected by the other nobles as leader of the Astures. Pelayo's kingdom was initially a rallying banner for existing guerilla forces.[13][14]

In the progress of the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, the main cities and administrative centers fell into the hands of Muslim troops. Control of the central and southern regions, such as the Guadalquivir and Ebro valleys, presented few problems for the newcomers, who used the existing Visigothic administrative structures, ultimately of Roman origin. However, in the northern mountains, urban centers (such as Gijón) were practically nonexistent and the submission of the country had to be achieved valley by valley. Muslim troops often resorted to the taking of hostages to ensure the pacification of the newly conquered territory.

After the first incursion of Tarik, who reached Toledo in 711, the Yemeni viceroy of Ifriqiya, Musa bin Nusayr, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar the following year and carried out a massive operation of conquest that would lead to the capture of Mérida, Toledo, Zaragoza and Lerida, among other cities. During the last phase of his military campaign, he reached the northwest of the Peninsula, where he gained control of the localities of Astorga and Gijón. In the latter city, he placed a small Berber detachment under a governor, Munuza, whose mission was to consolidate Muslim control over Asturias. As a guarantee of the submission of the region, some nobles – some argue that Pelayo was among them – had to surrender hostages from Asturias to Cordoba. The legend says that his sister was asked for, and a marriage alliance sought with the local Berber leader. Later on, Munuza would try to do the same at another mountain post in the Pyrenees, where he rebelled against his Cordoban Arab superiors. The Berbers had been converted to Islam barely a generation earlier, and were considered second rank to Arabs and Syrians.

The most commonly accepted hypothesis for the battle (epic as described by later Christian Asturian sources, but a mere skirmish in Muslim texts) is that the Moorish column was attacked from the cliffs and then fell back through the valleys towards present day Gijón, but it was attacked in retreat by the retinue and nearly destroyed. However, the only near-contemporary account of the events of the time, the Christian Chronicle of 754, makes no mention of the incident.

However, as is told in the Rotensian Chronicle [15] as well as in that of Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari,[16] Pelayo escaped from Cordoba during the governorship of al-Hurr (717–718) and his return to Asturias triggered a revolt against the Muslim authorities of Gijón. The identity of Pelayo, however, is still an open subject, and that is only one of the theories. The leader of the Astures, whose origin is debated by historians, lived at that time in Bres, in the district of Piloña, and Munuza sent his troops there under al-Qama. After receiving word of the arrival of the Muslims, Pelayo and his companions hurriedly crossed the Piloña and headed toward the narrow, easily defended valley of Mt. Auseva, taking refuge in one of its caves, Covadonga. After an attempted siege was abandoned due to the weather and the exposed position of the deep valley gorge, the troops are said to have exited through the high ports to the south, in order to continue their search-and-destroy mission against other rebels. There, the locals were able to ambush the Muslim detachment, which was nearly annihilated. The few survivors continued south to the plains of Leon, leaving the maritime districts of Asturias exposed.

The victory, relatively small, as only a few Berber soldiers were involved, resulted in great prestige for Pelayo and provoked a massive insurrection by other nobles in Galicia and Asturias who immediately rallied around him, electing him King or military Dux.

Under Pelayo's leadership, the attacks on the Berbers increased. Munuza, feeling isolated in a region increasingly hostile, decided to abandon Gijón and headed for the Plateau (Meseta) through the Mesa Trail. However, he was intercepted and killed by Astures at Olalíes (in the current district of Grado). Once he had expelled the Moors from the eastern valleys of Asturias, Pelayo attacked León, the main city in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, and secured the mountain passes, insulating the region from Moorish attack. Pelayo continued attacking those Berbers who remained north of the Asturian Mountains until they withdrew, but the latter mostly deserted their garrisons in response to the wider rebellion against Arab control from Cordoba. He then married his daughter, Ermesinda, to Alfonso, the son of Peter of Cantabria, the leading noble at the still-independent Visigothic duchy of Cantabria. His son Favila was married to Froiliuba.

Recent archaeological excavations have found fortifications in Mount Homon and La Carisa (near the Huerna and Pajares valleys) dated between the end of the seventh and beginning of the eighth centuries. The Berber fortifications included watchtowers and moats of almost two meters, in whose construction and defense many hundreds may have participated. That would have required a high degree of organization and firm leadership, probably by Pelayo himself.[17] Therefore, experts consider it probable that the construction of the defensive line was intended to prevent the reentry of Moors into Asturias through the mountain passes of Mesa and Pajares.[18]

.jpg.webp)

After Pelayo's victory over the Moorish detachment at the Battle of Covadonga, a small territorial independent entity was established in the Asturian mountains that was the origin of the kingdom of Asturias. Pelayo's leadership was not comparable to that of the Visigothic kings. The first kings of Asturias referred to themselves as "princeps" (prince) and later as "rex" (king), but the later title was not firmly established until the period of Alfonso II. The title of "princeps" had been used by the indigenous peoples of Northern Spain and its use appears in Galician and Cantabrian inscriptions, in which expressions like "Nícer, Príncipe de los Albiones"[19] (on an inscription found in the district of Coaña) and "princeps cantabrorum"[20] (over a gravestone of the municipality of Cistierna, in Leon). In fact, the Kingdom of Asturias originated as a focus of leadership over other peoples of the Cantabrian Coast that had resisted the Romans as well as the Visigoths and that were not willing to subject themselves to the dictates of the Umayyad Caliphate. Immigrants from the south, fleeing from Al-Andalus, brought a Gothic influence to the Asturian kingdom. However, at the beginning of the 9th century, Alfonso II's will cursed the Visigoths, blaming them for the loss of Hispania. The later chronicles on which knowledge of the period is based, all written during the reign of Alfonso III, when there was great Gothic ideological influence, are the Sebastianensian Chronicle (Crónica Sebastianense), the Albeldensian Chronicle (Crónica Albeldense) and the Rotensian Chronicle (Crónica Rotense).

During the first decades, the Asturian dominion over the different areas of the kingdom was still lax and so it had to be continually strengthened through matrimonial alliances with other powerful families from the north of the Iberian Peninsula. Thus, Ermesinda, Pelayo's daughter, was married to Alfonso, Dux Peter of Cantabria's son. Alfonso's son Fruela married Munia, a Basque princess from Alava, while his daughter Adosinda married Silo, a local chief from the area of Flavionavia, Pravia.

After Pelayo's death in 737, his son Favila (or "Fafila") was elected king. Fafila, according to the chronicles, was unexpectedly killed by a bear while hunting in one of the trials of courage normally required of the nobility of that era. However, there is no other such incident known from the long history of monarchs and others at the sport, and the case is suspiciously similar to the Roman legend of their first king, Romulus, taken by a sudden storm. The immediate consequence was that the rule of the Asturians passed to his brother-in-law, ruler of the neighboring independent domain, through a marriage alliance to Fafila's sister. The female ties and rights of inheritance were still respected, and in later cases would allow the regency or crown for their husbands too.

Pelayo founded a dynasty in Asturias that survived for decades and gradually expanded the kingdom's boundaries, until all of northwest Iberia was included by c. 775. The reign of Alfonso II from 791 to 842 saw further expansion of the kingdom to the south, almost as far as Lisbon.

Initial expansion

Favila was succeeded by Alfonso I, who inherited the throne of Asturias thanks to his marriage to Pelayo's daughter, Ermesinda. The Albeldensian Chronicle narrated how Alfonso arrived in the kingdom some time after the battle of Covadonga to marry Ermesinda. Favila's death made his access to the throne possible as well as the rise of one of the most powerful families in the Kingdom of Asturias, the House of Cantabria. Initially, only Alfonso moved to the court in Cangas de Onís, but, after the progressive depopulation of the plateau and the Middle Valley of the Ebro, where the main strongholds of the Duchy of Cantabria (e.g., Amaya, Tricio and the City of Cantabria) were located, the descendants of Duke Peter withdrew from Rioja towards the Cantabrian area and in time controlled the destiny of the Kingdom of Asturias.

Alfonso began the territorial expansion of the small Christian kingdom from its first seat in the Picos de Europa, advancing toward the west to Galicia and toward the south with continuous incursions in the Douro valley, taking cities and towns and moving their inhabitants to the safer northern zones. It eventually led to the strategic depopulation of the plateau, creating the Desert of the Duero as a protection against future Moorish attacks.[21]

The depopulation, defended by Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, is doubted today, at least concerning its magnitude.[21] Two main arguments are used to refute it: first, the minor toponymy was preserved in multiple districts; second, there are biological and cultural differences between the inhabitants of the Cantabrian zone and those of the central Plateau. What is true is that in the first half of the eighth century there was a process of rural growth that led to the abandonment of urban life and the organization of the population in small communities of shepherds. Several causes explain this process: the definitive collapse of the Roman Mediterranean economic system from the time of the late Roman Empire due to Arab conquests, the continuous propagation of epidemics in the area, and the abandonment of al-Andalus by the Berber regiments after the revolt of 740–741. All this made possible the emergence of a sparsely populated and ill-organized area that insulated the Asturian kingdom from the Moorish assaults and allowed its progressive strengthening.

The campaigns of kings Alfonso I and Fruela in the Duero valley were probably not very different from the raids that the Astures made in the same area in the pre-Roman era. The initial Asturian expansion was carried out mainly through Cantabrian territory (from Galicia to Vizcaya) and it was not until the reigns of Ordoño I and Alfonso III that the Kingdom of Asturias could take effective possession of the territories located south of the Cantabrian Mountains.

Fruela I, Alfonso I's son, consolidated and expanded his father's domains. He was assassinated by members of the nobility associated with the House of Cantabria.

Social and political transformations

Written sources are concise concerning the reigns of Aurelio, Silo, Mauregatus and Bermudo I. Generally this period, with a duration of twenty-three years (768–791), has been considered as a long stage of obscurity and retreat of the kingdom of Asturias. This version, defended by some historians, who even named this historical phase as that of the "lazy kings", derived from the fact that, during it, there were apparently no important military actions against al-Andalus. However, there were relevant and decisive internal transformations, which provided a foundation for the strengthening and the expansion of Asturias.

First, the first internal rebellion, led by Mauregato (783–788), occurred during those years. The rebellion removed Alfonso II from the throne (although he became king again later, from 791 to 842). This initiated a series of further rebellions whose principal leaders were members of ascending aristocratic palace groups and landowners who, based on the growing economic development of the area, tried to unseat the reigning family of Don Pelayo. The important rebellions of Nepociano, Aldroito and Piniolo, during the reign of Ramiro I (842–50), are part of this process of economic, social, political and cultural transformation of the Asturian kingdom that occurred during the eighth and ninth centuries.

Second, neighboring rebellions by Basques and Galicians failed, quashed by Asturian kings. These rebels took advantage of the unrest in the central and Eastern part of Asturias, and, on occasion, provided help to one or another contender for the throne: by providing refuge to Alfonso II in Alava after his flight; the support for Nepociano's rebellion in some Asturian areas; and the adherence of Galicians to the cause of Ramiro I.

Finally, other evidence suggests important internal transformations occurred during this time. Rebellions of freedmen (serbi, servilis orico and libertini, according to the Chronicles) occurred during the reign of Aurelio I. The property relationship between master and slave broke down progressively. This fact, together with the growing role of the individual and the restricted family, to the detriment of the extended family, is another indication that a new society was emerging in Asturias at the end of the eighth and beginning of the ninth centuries.

Fruela I (757–68) was succeeded by Aurelius (768–74), son of Fruela of Cantabria and Peter of Cantabria's grandson, who would establish the court in what is today the district of San Martín del Rey Aurelio, which previously belonged to Langreo. Silo (774–83) succeeded Aurelio after his death, and transferred the court to Pravia. Silo was married to Adosinda, one of the daughters of Alfonso I (and therefore, Pelayo's granddaughter).

Alfonso II was elected king after Silo's death, but Mauregato organized a strong opposition and forced the new king to withdraw to lands in Alava (his mother, Munia, was Basque), obtaining the Asturian throne. The king, despite the bad reputation attributed by history, had good relations with Beatus of Liébana, perhaps the most important cultural figure of the kingdom, and supported him in his fight against adoptionism. Legend says that Mauregato was Alfonso I's bastard son with a Moorish woman, and attributes to him the tribute of a hundred maidens. He was succeeded by Bermudo I, Aurelio's brother. He was called "the deacon", although he probably received only minor vows. Bermudo abdicated after a military defeat, ending his life in a monastery.

Recognition and later solidification

It was not until King Alfonso II (791–842) that the kingdom was firmly established, after Silo's subjugated Gallaecia and confirmed territorial gains in western Basque Country.[22] Ties with the Carolingian Franks also got closer and more frequent, with Alfonso II's envoys presenting Charlemagne with spoils of war (campaign of Lisbon, 797). Alfonso II introduced himself as "an Emperor Charlemagne's man",[23] suggesting some kind of suzerainty.[24] During Alfonso II's reign, a probable reaction against indigenous traditions took place in order to strengthen his state and grip on power, by establishing in the Asturian Court the order and ceremonies of the former Visigoth Kingdom.[23] Around this time, the holy bones of James, son of Zebedee were declared to have been found in Galicia at Iria Flavia. They were considered authentic by a contemporary pope of Rome. However, during the Asturian period, the final resting place of Eulalia of Mérida, located in Oviedo, became the primary religious site and focus of devotion.

Alfonso II also repopulated parts of Galicia, León and Castile and incorporated them into the Kingdom of Asturia while establishing influence over parts of the Basques. The first capital city was Cangas de Onís, near the site of the battle of Cavadonga. Then in Silo's time, it was moved to Pravia. Alfonso II chose his birthplace of Oviedo as the capital of the kingdom (circa 789).

Ramiro I began his reign by capturing several other claimants to the throne, blinding them, and then confining them to monasteries. As a warrior he managed to defeat a Viking invasion after the Vikings had landed at Corunna, and also fought several battles against the Moors.

When he succeeded his father Ramiro, Ordoño I (850–66) repressed a major revolt amongst the Basques in the east of the kingdom. In 859, Ordoño besieged the fortress of Albelda, built by Musa ibn Musa of the Banu Qasi, who had rebelled against Cordoba and became master of Zaragoza, Tudela, Huesca and Toledo. Musa attempted to lift the siege in alliance with his brother-in-law García Iñiguez, the king of Pamplona, whose small realm was threatened by the eastwards expansion of the Asturian monarchy. In the battle that followed, Musa was defeated and lost valuable treasures in the process, some of which were sent as a gift to Charles the Bald of Francia. Seven days after the victory, Albelda fell and, as the chronicler records, "its warriors were killed by the sword and the place itself was destroyed down to its foundations." Musa was wounded in the battle and died in 862/3; soon thereafter, Musa's son Lubb, governor of Toledo, submitted himself to the Asturian king for the rest of Ordoño's reign.

When Alfonso III's sons forced his abdication in 910, the Kingdom of Asturias split into three separate kingdoms: León, Galicia and Asturias. The three kingdoms were eventually reunited in 924 (León and Galicia in 914, Asturias later) under the crown of León. It continued under that name until incorporated into the Kingdom of Castile in 1230, after Ferdinand III became joint king of the two kingdoms.

Viking raids

The Vikings invaded Galicia in 844, but were decisively defeated by Ramiro I at Corunna.[7] Many of the Vikings' casualties were caused by the Galicians' ballistas – powerful torsion-powered projectile weapons that looked rather like giant crossbows.[7][25] Seventy of the Vikings' longships were captured on the beach and burned.[7][26][27] A few months later, another fleet took Seville. The Vikings found in Seville a population which was still largely Gothic and Romano-Spanish.[28] The Gothic elements were important in the Andalusian emirate.[29] Musa ibn Musa, who took a leading part in the defeat of the Vikings at Tablada, belonged to a powerful Muwallad family of Gothic descent.

Vikings returned to Galicia in 859, during the reign of Ordoño I. Ordoño was at the moment engaged against his constant enemies, the Moors, but a count of the province, Don Pedro, attacked the Vikings and defeated them,[30] inflicting severe losses upon them.[31] Ordoño's successor, Alfonso III, strove to protect the coast against attacks from Vikings or Moors. In 968, Gunrod of Norway attacked Galicia with 100 ships and 8,000 warriors.[32] They roamed freely for years and even occupied Santiago de Compostela. A Galician count of Visigothic descent, Gonzalo Sánchez, ended the Viking adventure in 971, when he launched an attack with a powerful army that defeated the Vikings in a bloody battle, and captured Gunrod, who was subsequently executed along with his followers.

Religion

Remnants of Megalithic and Celtic paganism

Although the earliest evidence of Christian worship in Asturias dates from the 5th century, evangelisation did not make any substantial progress until the middle of the sixth century, when hermits like Turibius of Liébana and monks of the Saint Fructuoso order gradually settled in the Cantabrian mountains and began preaching the Christian doctrine.

Christianisation progressed slowly in Asturias and did not necessarily supplant the ancient pagan divinities. As elsewhere in Europe, the new religion coexisted syncretically with features of the ancient beliefs. In the sixth century, bishop San Martín de Braga complained in his work De correctione rusticorum about the Galician peasants being attached to the pre-Christian cults: "Many demons, who were expelled from the heavens, settled in the sea, in the rivers, fountains and forests, and have come to be worshipped as gods by ignorant people. To them they do their sacrifices: in the sea they invoke Neptune, in the rivers the Lamias; in the fountains the Nymphs, and in the forests Diana."[33]

In the middle of the Sella valley, where Cangas de Onís is located, there was a dolmen area dating back to the megalithic era, and was likely built between 4000 and 2000 BC. Chieftains from the surrounding regions were ritually buried here, particularly in the Santa Cruz dolmen. Such practices survived the Roman and Visigothic conquests. Even in the eighth century, King Favila was buried there, along with the bodies of tribal leaders. Although the Asturian monarchy fostered the Christianisation of this site, by constructing a church, to this day there are still pagan traditions linked with the Santa Cruz dolmen. It is said that xanas (Asturian fairies) appear to visitors, and magical properties are ascribed to the soil of the place.

According to an inscription found in the Santa Cruz church, it was consecrated in 738 and was presided by a vates called Asterio. The word vates is uncommon in Catholic documents and epitaphs, where the word presbyterus (for Christian priests) is preferred. However, vates was used in Latin to denote a poet who was clairvoyant, and according to the Ancient Greek writers Strabo, Diodorus Siculus, and Posidonius, the vates (ουατεις) were also one of three classes of Celtic priesthood, the other two being the druids and the bards. Some historians think that Asterio held a religious office which combined elements of paganism and Christianity, while others think he may be linked to the Brythonic refugees that settled in Britonia (Galicia) in the 6th century. The Parrochiale Suevorum, an administrative document from the Kingdom of the Suebi, states that the lands of Asturias belonged to the Britonian See, and some features of Celtic Christianity spread to Northern Spain. This is evidenced by the Celtic tonsure, which the Visigothic bishops who participated in the Fourth Council of Toledo condemned.[34]

Still extant Galician legends relate to monks who travelled by sea to the Paradise Islands, like those of Saint Amaro, Trezenzonio or The Legend of Ero of Armenteira. These stories have many parallels with those of Brendan the navigator, Malo of Wales, and the stories of the Irish immrama.

Asturian kings promoted Christianity and did not base their power on indigenous religious traditions, unlike other medieval European kings such as Penda of Mercia or Widukind, but on Christian sacred scriptures (in particular, the books of Revelation, Ezekiel and Daniel) and the Church Fathers. These furnished the new monarchy with its foundational myths. They did not need to draft new laws since the Visigothic Code was the referential code, at least since the arrival of new influences including exiles, prisoners from the central area of al-Andalus in the 770s along with their mixed Berber-Arabic and Gothic legacy. This combined with governmental and religious ideas imported from Charlemagne's Frankish Kingdom (Alcuin-Beatus of Liébana).

Adoptionism

The foundations of Asturian culture and that of Christian Spain in the High Middle Ages were laid during the reigns of Silo and Mauregatus, when the Asturian kings submitted to the authority of the Umayyad emirs of the Caliphate of Córdoba. The most prominent Christian scholar in the Kingdom of Asturias of this period was Beatus of Liébana, whose works left an indelible mark on the Christian culture of the Reconquista.

Beatus was directly involved in the debate surrounding adoptionism, which argued that Jesus was born a man, and was adopted by God and acquired a divine dimension only after his passion and resurrection. Beatus refuted this theological position, championed by such figures as Elipando, bishop of Toledo.

The adoptionist theology had its roots in Gothic Arianism, which denied the divinity of Jesus, and in Hellenistic religion, with examples of heroes like Heracles who, after their death attained the apotheosis. Likewise, as Elipandus's bishopric of Toledo was at the time within the Muslim Caliphate of Cordoba, Islamic beliefs which acknowledged Jesus as a Prophet, but not as the Son of God, influenced the formation of adoptionism. However, the adoptionist theology was opposed strongly by Beatus from his abbey in Santo Toribio de Liébana. At the same time, Beatus strengthened the links among Asturias, the Holy See, and the Carolingian Empire, and was supported in his theological struggle by the Pope and by his friend Alcuin of York, an Anglo-Saxon scholar who had settled among the Carolingian court in Aachen.

Millennialism

The most transcendental works of Beatus were his Commentaries to Apocalypse, which were copied in later centuries in manuscripts called beati, about which the Italian writer Umberto Eco said: "Their splendid images gave birth to the most relevant iconographic happening in the History of Mankind".[35] Beatus develops in them a personal interpretation of the Book of Revelation, accompanied by quotes from the Old Testament, the Church Fathers and fascinating illustrations.

In these Commentaries a new interpretation of the apocalyptic accounts is given: Babylon no longer represents the city of Rome, but Córdoba, seat of the Umayyad emirs of al-Andalus; the Beast, once a symbol of the Roman Empire, now stands for the Islamic invaders who during this time threatened to destroy Western Christianity, and who raided territories of the Asturian Kingdom.

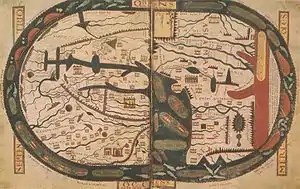

The prologue to the second book of the Commentaries contains the Beatus map, one of the best examples of a mappa mundi of the high medieval culture. The purpose of this map was not to represent the world cartographically, but to illustrate the Apostles' diaspora in the first decades of Christianity. Beatus took data from the works of Isidore of Seville, Ptolemy and the Bible. The world was represented as a land disc surrounded by the Ocean and divided in three parts: Asia (upper semicircle), Europe (lower left quadrant) and Africa (lower right quadrant). The Mediterranean Sea (Europe-Africa), the Nile River (Africa-Asia), the Aegean Sea, and the Bosphorus (Europe-Asia) were set as the boundaries between the different continents.

Beatus believed that the Apocalypse described in the book of Revelation was imminent, which would be followed by 1290 years of domination by the Antichrist. Beatus followed the views of Augustine of Hippo, whose work, The City of God, influenced the Commentaries which followed the premise that the history of the world was structured in six ages. The first five ones extended from the creation of Adam to the Passion of Jesus, while the sixth, subsequent to Christ, ends with the unleashing of the events prophesied in the book of Revelation.

Millennialist movements were very common in Europe at that time. Between 760 and 780, a series of cosmic phenomena stirred up panic among the population of Gaul; John, a visionary monk, predicted the coming of the Last Judgment during the reign of Charlemagne. In this time the Apocalypse of Daniel appeared, a Syriac text redacted during the rule of the empress Irene of Athens, wherein wars between the Arabs, the Byzantines and the Northern peoples were prophesied. These wars would end with the coming of the Antichrist.

Events taking place in Hispania (Islamic rule, the adoptionist heresy, the gradual assimilation of the Mozarabs) were, for Beatus, signals of the imminent apocalypse. aeon. As Elipandus describes in his Letter from the bishops of Spania to their brothers in Gaul, the abbot of Santo Toribio went so far as to announce to his countrymen the coming of the End of Time on Easter of the year 800. On the dawn of that day, hundreds of peasants met around the abbey of Santo Toribio, waiting, terrified, for the fulfillment of the prophecy. They remained in there, without eating for a day and half, until one of them, named Ordonius, exclaimed: "Let us eat and drink, so that if the End of the World comes we are full!".

The prophetic and millennialist visions of Beatus produced an enduring mark in the development of the Kingdom of Asturias: the Chronica Prophetica, which was written around 880 CE, predicted the final fall of the Emirate of Córdoba, and the conquest and redemption of the entire Iberian Peninsula by king Alfonso III. Millennialist imagery is also reflected throughout the kingdom in the Victory Cross icon, the major emblem of the Asturian kingdom, which has its origins in a passage of the Revelation book in which John of Patmos relates a vision of the Second Coming. He sees Jesus Christ seated in his majesty, surrounded by clouds and affirming: "I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the ending, saith the Lord, which is, and which was, and which is to come, the Almighty".[37] It is true that usage of the labarum was not restricted to Asturias, and dates back to the time of Constantine the Great, who used this symbol during the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. However, it was in Asturias where the Cruz de la Victoria attained a general use: in nearly every pre-Romanesque church this icon is engraved,[38][39] often accompanied with the expression "Hoc signo tuetur pius, in hoc signo vincitur inimicus",[40] that became the royal motto of the Asturian monarchs.

Camino de Santiago

Another of the major spiritual legacies of the Asturian kingdom is the creation of one of the most important ways of cultural transmission in European history: the Camino de Santiago. The first text which mentions St. James' preaching in Spain is the Breviarius de Hyerosolima, a 6th-century document which stated that the Apostle was buried in an enigmatic place called Aca Marmarica. Isidore of Seville supported this theory in his work De ortu et obitu patrium. One hundred and fifty years later, in the times of Mauregato, the hymn O Dei Verbum rendered St. James as "the golden head of Spain, our protector and national patron" and a mention is made of his preaching in the Iberian Peninsula during the first decades of Christianity. Some attribute this hymn to Beatus, although this is still discussed by historians.

The legend of St. James gained support during the reign of Alfonso II. The period was marked by Alfonso II's reaching out to Charlemagne for military assistance and importation of similar royal ceremonies and governmental structures. Galician Pelagius the Hermit claimed to observe a mysterious brightness during several nights over the Libredon forest, in Iria Flavia diocese. Angelic songs accompanied the lights. Impressed by this phenomenon, Pelayo appeared before the bishop of Iria Flavia, Theodemir, who – after having heard the hermit – visited the location with his retinue. Legend has it that in the depths of the forest was found a stone sepulchre with three corpses, which were identified as those of St. James, son of Zebedee, and his two disciples, Theodorus and Atanasius. According to the legend, King Alfonso was the first pilgrim who had come to see the Apostle. During his travels he was guided at night by the Milky Way, which from then on acquired the name of Camino de Santiago.

The founding of the alleged St. James tomb was a formidable political success for the Kingdom of Asturias: Now Asturias could claim the honour of having the body of one of the apostles of Jesus, a privilege shared only with Asia (Ephesus) where John the Apostle was buried, and Rome, where the bodies of Saint Peter and Saint Paul rested. As of the early 12th century, Santiago de Compostela grew to become one of the three sacred cities of Christianity, together with Rome and Jerusalem. In later centuries, many Central European cultural influences travelled to Iberia through the Way of St. James, from the Gothic and Romanesque styles, to the Occitan lyric poetry.

However, the story of the "discovery" of the remains of the Apostle shows some enigmatic features. The tomb was found in a place used as a necropolis since the Late Roman Empire, so it is possible that the body belonged to a prominent person of the area. British historian Henry Chadwick hypothesized the tomb of Compostela actually hold the remains of Priscillian. Historian Roger Collins holds that the identification of the relics (at any rate nothing close to a full body) with Saint James is related to the translation of the remains found under a 6th-century church altar in Mérida, where various saint names are listed, Saint James among them. Other scholars, like Constantino Cabal, highlighted the fact that several Galician places, such as Pico Sacro, Pedra da Barca (Muxía) or San Andrés de Teixido, were already draws for pagan pilgrimage in pre-Roman times. Pagan beliefs held these places as the End of the World and as entrances to the Celtic Otherworld. After the discovery of Saint James' tomb, the gradual Christianization of those pilgrimage routes began.

Mythology

Since the Chronicles of the Asturian kingdom were written a century and a half after the battle of Covadonga, there are many aspects of the first Asturian kings that remain shrouded in myth and legend.

Although the historicity of Pelayo is beyond doubt, the historical narrative describing him includes many folktales and legends. One of them asserts that, prior to the Muslim invasion, Pelayo went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, the sacred city of Christianity. However, there is no extant evidence of this.

Likewise, it is also said that the Cruz de la Victoria was at first carved in an oak's log by a lightning strike.[41] The core of this story contains two elements of major importance in the Asturian folklore. On one hand, lightning was the ancient symbol of the Astur god Taranis, and in Asturian mythology was thought to be forged by the Nuberu, lord of clouds, rain and wind. On the other hand, the oak tree is the symbol of the Asturian royalty and in reliefs of the Abamia Church (where Pelayo was buried) leaves of that tree are shown.

The Covadonga area is also rich with astonishing stories, such as the one which is said to have happened in a shepherd village where today Lakes Enol and Ercina are situated. Mary, mother of Jesus, disguised as a pilgrim, is said to have visited that village and asked for food and shelter from every house. She was rudely rejected by every person, except for a shepherd who gave her refuge and warmly shared everything he had. On the following day, as punishment for their lack of hospitality, a flood of divine origin devastated the village, which completely covered everything except the cottage of the good shepherd. In front of him, the mysterious guest started to cry, and her tears became flowers when they reached the floor. Then the shepherd realized that the pilgrim was actually Mary.

There are also myths about the Asturian monarchy that are rooted in Jewish and Christian traditions rather than pagan ones: the Chronica ad Sebastianum tells of an extraordinary event that happened when Alfonso I died. While the noblemen were holding a wake for him, there could be heard celestial canticles sung by angels. They recited the following text of the Book of Isaiah (which happens to be the same that was read by the Mozarabic priests during the Vigil of the Holy Saturday):

I said in the cutting off of my days, I shall go to the gates of the grave: I am deprived of the residue of my years.

I said, I shall not see the LORD, even the LORD, in the land of the living: I shall behold man no more with the inhabitants of the world.

Mine age is departed, and is removed from me as a shepherd's tent: I have cut off like a weaver my life: he will cut me off with pining sickness: from day even to night wilt thou make an end of me.

I reckoned till morning, that, as a lion, so will he break all my bones: from day even to night wilt thou make an end of me.

Like a crane or a swallow, so did I chatter: I did mourn as a dove: mine eyes fail with looking upward: O LORD, I am oppressed; undertake for me.— Is. 38:10–14

This canticle was recited by Hezekiah, king of Judah, after his recovery from a serious illness. In these verses, the king regretted with distress his departure to sheol, the Jewish underworld, a shady place where he would not see God nor men any more.

Asturias also has examples of the king in the mountain myth. According to the tradition, it is still today possible to see king Fruela walking around the Jardín de los Reyes Caudillos[42] (a part of the Oviedo Cathedral), and it is said that his grandson, the famous cavalier Bernardo del Carpio, sleeps in a cave in the Asturian mountains. The story tells that one day a peasant went into a certain cave to retrieve his lost cow and heard a strong voice who declared to be Bernardo del Carpio, victor over the Franks in Roncevaux.[43] After saying he had lived alone for centuries in that cave, he told the peasant: "Give me your hand, so that I can see how strong are men today". The shepherd, scared, gave him the horn of the cow, which, when seized by the giant man, was immediately broken. The poor villager ran away terrified, but not without hearing Bernardo say: "Current men are not like those who helped me to kill Frenchmen in Roncevaux".[44][45]

Ercina lake, Covadonga. According to the legend, under its waters a village—or perhaps a city—is hidden.

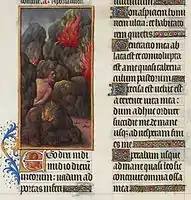

Ercina lake, Covadonga. According to the legend, under its waters a village—or perhaps a city—is hidden. Illustration of Hezekiah's Canticle belonging to the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The Asturian monarchs often took the kings of the Old Testament as their models.

Illustration of Hezekiah's Canticle belonging to the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The Asturian monarchs often took the kings of the Old Testament as their models.

Legacy

This kingdom is the birthplace of an influential European medieval architectural style: Asturian pre-Romanesque. This style of architecture was founded during the reign of Ramiro I.

This small kingdom was a milestone in the fight against the adoptionist heresy, with Beatus of Liébana as a major figure. In the time of Alfonso II, the shrine of Santiago de Compostela was "found". The pilgrimage to Santiago, Camiño de Santiago, was a major nexus within Europe, and many pilgrims (and their money) passed through Asturias on their way to Santiago de Compostela.

See also

Citations

- Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell. p. 49. ISBN 0-631-19405-3.

- Ackermann, Peter (2007). Pilgrimages and Spiritual Quests in Japan. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 9781134350469.

- Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell. p. 49. ISBN 0-631-19405-3.

- Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797. Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US: Blackwell. p. 49. ISBN 0-631-19405-3.

- Medieval Frontiers: Concepts and Practices. Routledge. 2017.

- Roger Collins, Caliphs and Kings: Spain, 796–1031, 65.

- Haywood, John (2015). Northmen: The Viking Saga, AD 793–1241. p. 166. ISBN 9781781855225.

- Flood, Timothy M. (2018). Rulers and Realms in Medieval Iberia, 711–1492. McFarland. p. 30.

- J. Gil, Crónicas Asturianas, 1985, p. 176

- Menéndez Pidal, Ramón (1906). Primera crónica general. Estoria de españa de alfonso x (2022 ed.). Biblioteca Digital de Castilla y León. p. 357. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- Collins, Roger (1983). Early Medieval Spain. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-312-22464-8.

- Collins, Roger (1983). Early Medieval Spain. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 229. ISBN 0-312-22464-8.

- Alexander, Leslie M.; Walter C Rucker JR (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History. ISBN 9781851097746. Retrieved 2014-01-21 – via Google Břker.

- Smedley, Edward; Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John (1845). Encyclopćdia metropolitana; or, Universal dictionary of knowledge ... Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Retrieved 2014-01-21 – via Google Břker.

- This is the chronicle of Alfonso III of Asturias in which Pelayo is considered the successor of the kings of Toledo, with the clear goal of establishing Alfonso's political legitimacy.

- A Maghrebi historian of the 16th century who died in Cairo, Egypt, and who could have used the Rotensian Chronicle and rewritten it eight centuries later, making it useless as a historical document.

- La Nueva Espaa. "La Nueva Espaa – Diario Independiente de Asturias". Archived from the original on 2007-03-11.

- La Nueva Espaa. "La Nueva Espaa – Diario Independiente de Asturias". Archived from the original on 2007-03-11.

- The Asturian writer Juan Noriega made him one of the main characters of La Noche Celta (The Celtic Night), set in the castle of Coaña.

- Doviderio, Príncipe de los Cántabros.

- Glick 2005, p. 35

- Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797. Oxford, UK / Cambridge, US: Blackwell. p. 165. ISBN 0-631-19405-3.

- Collins, Roger (1983). Early Medieval Spain. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-312-22464-8.

- Sholod, Barton (1966). Charlemagne in Spain: The Cultural Legacy of Roncesvalles. Librairie Droz. p. 42. ISBN 2600034781.

- Brink, Stefan; Price, Neil (eds.). The Viking World. Routledge.

- Kendrick, Sir Thomas D. (24 October 2018). A History of the Vikings. ISBN 9781136242397.

- Oman, Charles (1924). England Before the Norman Conquest. p. 422. ISBN 9785878048347.

- Cf. Levi-Provencal, L'Espagne Muselmane au Xe siecle, 36; Histoire, 1 78

- Levi-Provencal, Histoire, III 184ff

- Keary, Charles. The Viking Age. Jovian Press.

- Kendrick, Sir Thomas D. (24 October 2018). A History of the Vikings. ISBN 9781136242397.

- "10 Most Savage Viking Voyages Of All Time". 29 December 2017.

- In Latin: "Et in mare quidem Neptunum appellant, in fluminibus Lamias, in fontibus Nymphas, in silvis Dianas, quae omnia maligni daemones et spiritus nequam sunt, qui homines infideles, qui signaculo crucis nesciunt se munire, nocent et vexant".

- Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, "Historia de los heterodoxos españoles I", Madrid, 1978, chapter II, note 48

- Umberto Eco wrote an essay about them, Beato di Liebana (1976)

- "And the woman was arrayed in purple and scarlet colour, and decked with gold and precious stones and pearls, having a golden cup in her hand full of abominations and filthiness of her fornication: And upon her forehead was a name written, MYSTERY, BABYLON THE GREAT, THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS AND ABOMINATIONS OF THE EARTH."

- Revelation, 1.8.

- "The Cruz de la Victoria engraved in stone". Archived from the original on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- Archived February 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "With this sign thou shalt defend the pious, with this sign thou shalt defeat the enemy".

- Simbología mágico-tradicional, Alberto Álvarez Peña, page 147.

- Relatos legendarios sobre los orígenes políticos de Asturias y Vizcaya en la Edad Media, Arsenio F. Dacosta, Actas del VII Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Española de Semiótica (Volumen II).

- In medieval Spain, it was commonly thought that it was the Asturians or the Moors, and not the Basques, who beat the Franks in this battle.

- Bernardo del Carpiu y otros guerreros durmientes Alberto Álvarez Peña

- Los maestros asturianos (Juan Lobo, 1931)

General references

- Glick, Thomas (2005), Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-14771-3