History of Hobart

The modern history of the Australian city of Hobart (formerly 'Hobart Town', or 'Hobarton') in Tasmania dates to its foundation as a British colony in 1804. Prior to British settlement, the area had been occupied for at least 8,000 years, but possibly for as long as 35,000 years,[1] by the semi-nomadic Mouheneener tribe, a sub-group of the Nuenonne, or South-East tribe.[2] The descendants of the indigenous Tasmanians now refer to themselves as 'Palawa'.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

Little is known about the region from prehistoric times. As with many other Australia cities, urbanisation has destroyed much of the archaeological evidence of indigenous occupation, although Aboriginal middens are often still present in coastal areas.[3]

The first European settlement in the Hobart area began in 1803 as a penal colony and defensive outpost[4] at Risdon Cove on the eastern shores of the Derwent River, amid British concerns over the presence of French explorers in the South Pacific. In 1804 it was moved to a better location at the present site of Hobart at Sullivans Cove, making it the second oldest city in Australia.

The convict past haunted the city for decades, and Hobart's prominent Georgian architecture of the era served as a constant reminder of the 'social stain' some of its citizens feared they could never erase. Gradually this unpromising beginning was transformed into a quiet, conservative, strongly class-conscious society.[5] However, many of the former convicts proved to be hard-working and enterprising, establishing businesses and families that still play a prominent role in Tasmanian society.

Since that time, the city has grown from what was approximately one square mile around the mouth of Sullivans Cove to stretch in a generally north–south direction along both banks of the Derwent River, from 22 km inland from the estuary at Storm Bay to the point where the river reverts to fresh water at Bridgewater. The city sits on low-lying hills at the eastern foot of Mount Wellington.[6]

From the foundation of the settlement, Hobart has remained the administrative centre of Tasmania, and from the time that Tasmania was granted responsible self-government in 1856 it has been the capital city of Tasmania.[6]

Hobart's growth has been slow due to its geographic isolation, and the city has experienced extreme economic boom and bust periods throughout its history. The city grew from being a defensive outpost and penal colony to become a world centre of whaling and shipbuilding, only to suffer a major economic and population decline in the late 19th century.

The early 20th century saw another period of growth on the back of mining, agriculture and other primary industries, but the world wars had a very negative effect on Hobart, with a severe loss of working age men. Like most of Australia, the post-war years saw an influx of new migrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, such as Italy, Greece, Yugoslavia and Poland.[7]

In the later years of the 20th century, migrants increasingly arrived to settle in Hobart from Asia. Despite the rise in migration from parts of the world other than the United Kingdom and Ireland, the population of Hobart remains predominantly ethnically Anglo-Celtic, and has the highest percentage per capita of Australian born residents of all the Australian capital cities.[8]

Hobart is a major deep-water port for Southern Ocean shipping, and the last port of call for Australian Antarctic Division and French expeditions to Antarctica. Hobart is also a common port of call for naval vessels from many countries due to the deep harbour of the Derwent River. US Navy vessels often stop for shore leave when returning to the United States from the Middle East.

Hobart is a city defined by its geographical position, history and heritage. Classical examples of Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian architecture abound throughout the city, and along with more recently built forms, these buildings define Hobart's character as a city.

Hobart has experienced a boom in tourism, and the low cost of living and relaxed way of life have attracted mainland Australians and new migrants to move to the city. Although Hobart has experienced a much slower rate of growth than mainland Australian cities, particularly during the 20th century, Hobart has a stable population, a reasonably strong economy, a clean environment, a healthy sports, arts and culture scene.

Etymology

The etymology of the name of Hobart comes from the first Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land, David Collins, who named the new settlement in honour of the then Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Robert Hobart, 4th Earl of Buckinghamshire, the Lord Hobart.[9] It was originally referred to as 'Hobart Town', which was often shortened to 'Hobarton', but by 1842 it had grown large enough to officially be recognised as a city, and from 1 January 1881 the 'Town' was formally dropped from its name, leaving the modern name of simply 'Hobart'.[10]

Geography

The city of Hobart is located in the south eastern part of the island of Tasmania, at 42°S, 147°E. It is approximately 22 kilometres from the mouth of the Derwent River at Storm Bay. Hobart is built around Sullivans Cove, a small bay formed where the Hobart Rivulet and the Derwent River join. The location was chosen as a location for a settlement due to the deep-water harbour that allows easy access for shipping, the sheltered anchorage that Sullivans Cove provides, and the freshwater supply from Hobart Rivulet.

The main part of the city runs along the western shore of the Derwent River in a north–south direction, but the eastern shore residential suburbs are also extensive. The eastern shore has many low hills and a small mountain ridge known as the Meehan Range. The western shore is partially flat at sea level but rises steeply away from the shore to the foothills.

Deep gullies are situated between the hill ridges, most of which reach to around 500–800 m in height. Mount Wellington is the most prominent feature of the Wellington Range. The Derwent Valley stretches northwards and is flat farmland and rolling green hills that follows the winding course of the river.[11]

Prehistory

The prehistory of the Hobart region is poorly understood. At the time of settlement by the British, it is estimated that approximately 1000 to 5000 people lived in Tasmania, divided into eight tribal groups. It was the semi-nomadic Mouheneener tribe, a sub-group of the Nuenonne, or 'South-East' tribe, who were first affected by European settlement, as Hobart Town was founded in their traditional hunting grounds.

The Nuenonne had no permanent settlements at Sullivans Cove, or anywhere else in Tasmania, living as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Early Europeans described the Nuenonne as living in crude bark huts established around a fire at movable camping grounds as they travelled about their region.

The French described them as a friendly peaceful people who lived a happy, simple life. The best description of them came from Captain James Cook RN, on his visit to the Derwent River in 1777. Cook described the Nuenonne as:

...Being of middling stature, slender and naked. On different parts of their bodies were ridges, both straight and curved, raised in the skin: the hair of the head and beard was smeared with red ointment.

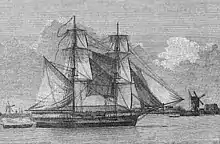

During the first visits to Tasmania by European explorers, the Nuenonne, normally in parties of about eight men, were often very welcoming, greeting explorers from the shore with friendly shouts and exchanging food and water for trinkets. At first they thought the Europeans were spirits who arrived on the backs of great birds, believing the European ship's sails looked like seagull wings. However, tension grew quickly amongst the Nuenonne as they realised the Europeans were intending to establish a permanent settlement.[12]

By the 1820s, the expansion of European settlements throughout the island, and massive growth in pastoralism came at the expense of the Aborigines, who began to resist the intruders. Clashes became more frequent, and tit-for-tat killings became common. Although exact numbers for the death toll were not recorded, estimates vary between 5–9,000. Towards the end of the 1820s the conflict had become so bad that martial law was declared, and the conflict soon grew into the Black War.[12]

By 1831, there were only 200 natives left. Governor George Arthur's attempts to capture and resettle them failed with his disastrous "Black Line" policy. George Augustus Robinson's efforts to resettle them at Flinders Island resulted in the extermination of all the full-blooded native peoples by introduced European diseases such as smallpox, influenza and pneumonia. By 1847 there were only 44 native Tasmanians left, and the last full-blooded Aborigine, Trugannini, died in 1876. Today their race primarily survives in mixed-blood descendants of the women enslaved by Bass Strait whalers and sealers.[12]

The expansion and urbanisation of Hobart has destroyed much of the archaeological evidence of prior indigenous occupation, although Aboriginal middens are often still present in coastal areas.[3] As a result, it is difficult for archaeologists and anthropologists to gain a full understanding of the way of life of the Tasmanian Aborigines prior to European settlement.

European exploration

The Dutch crew of Abel Janszoon Tasman aboard Heemskirk and Zeehaen was the first group of Europeans to sight Tasmania. Leaving the Dutch colony of Batavia in Java (now Jakarta, Indonesia) in August 1642, they charted the Tasmanian coastline in November 1642 (though they did not determine that it was an island), and named it Van Diemen's Land, in honour of the Dutch governor of the Dutch East Indies, Anthony van Diemen.[13] Although the ship did not contact the indigenous Tasmanians at this time, the sighting of the Dutch ships may have led to the creation of myths about spirits riding on great seabirds amongst the Tasmanians.

The next visit to the River Derwent was by the Frenchman Marion du Fresne who arrived in 1773 with the ships Mascarin and Castries. As French and British rivalries grew towards the end of the 18th century, both nations sent regular scientific missions to the region.

The English explorers Tobias Furneaux, aboard HMS Adventure in 1773, and James Cook, aboard HMS Resolution in 1777, both described the shores of the Derwent as a suitable location for resupplying and watering their ships.[14]

One of Cook's Resolution crew in 1777, William Bligh, returned to the Derwent River for a second time in command of the Bounty on his fateful journey to Tahiti in 1788 that ended in mutiny by his crew. John Cox, aboard Mercury in 1789, closely followed Bligh. In the 1790s, the French and English continued to explore the area and chart parts of Tasmania's coast. William Bligh returned to the Derwent River in 1792, this time with the ships Providence and Assistant, again en route to Tahiti. He had been ordered to complete his previous mission of obtaining breadfruit from Tahiti for the West Indian plantations, and remembered the Derwent's favourable position to stop en route.

The following year, French explorers Bruni d'Entrecasteaux and Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec, who were in command of Recherche and the Espérance sailed into the river and charted it more extensively in the course of their search for Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse. He named the river 'Riviere du Nord'. During the stopover, his expedition also established a vegetable garden at Recherche Bay for use by future expeditions.[15][16]

A few months later, the English captain, Sir John Hayes also sought shelter for his ships Duke of Clarence and Duchess of Bengal there. It was during this visit that Hayes named the river as the 'Derwent River', in honour of the River Derwent in Cumbria.[15][17]

The next visit to the Derwent River came from George Bass and Matthew Flinders in 1798 and 1799, when they circumnavigated Tasmania aboard the Norfolk, being the first Europeans to prove that Tasmania was an island. British interest in the island then waned for the next four years.

1803 British settlement

Although several European explorers had navigated along the coast of Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) between the 1770s and 1790s, a strong English interest in the Derwent River only began with the return of English Royal Navy Captain William Bligh in 1792 aboard HMS Providence. He stopped briefly in Adventure Bay to take on fresh water before continuing his voyage.[15]

From 1792 until 1802, France and Great Britain had been embroiled against each other in the French Revolutionary Wars, and growing French interest in the South Pacific alarmed the colonists in Sydney. An expedition in 1802 to survey Van Diemen's Land by French explorers Nicolas Baudin and Louis de Freycinet aboard Géographe, Casuarina, and Naturaliste, stopped in the Derwent River to make observations of the indigenous Tasmanians, and the native flora and fauna.[18]

With Bass and Flinders' confirmation in 1798 that Van Diemen's Land was an island, the British claim to the east coast of Australia was not legally valid for Van Diemen's Land. Baudin's presence there caused alarm at the prospect of the French establishing a rival colony, and the Governor of New South Wales, Philip Gidley King dispatched a request to the Colonial Office in London for permission to establish a new settlement there.

Whilst King awaited news from London regarding Van Diemen's Land, separate news arrived that the short lived peace with France had been broken by the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars. King decided he could not afford to await word from London and risk France establishing a naval base on Van Diemen's Land.

Acting on his own initiative, he dispatched an expedition under the command of a young 23-year-old Lieutenant John Bowen to establish a colony there. Bowen was in command of the whaler Albion. Accompanying him were 21 male and three female convicts, guarded by a company of soldiers of the New South Wales Corps, as well as a small number of free settlers. The supply ship, the Lady Nelson arrived on 8 September 1803, and 'Albion arrived on 13 September 1803, thereby creating a presence in Van Diemen's Land for the British.[6]

At the same time David Collins had been dispatched from London in response to King's initial request, and departed from England in April 1803, in command of HMS Calcutta with orders to establish a colony at Port Phillip. Collins had been a member of the First Fleet which had founded Sydney 15 years earlier, and the Colonial Office felt this experience would be invaluable in the creation of a second settlement.[19]

Collins arrived in Port Phillip Bay in October 1803. After establishing a short lived settlement at Sullivan Bay, near the current site of Sorrento, he wrote to Governor King, expressing his dissatisfaction with the location, and seeking permission to relocate the settlement to the Derwent River. Realising the fledgling settlement at Risdon Cove would be well reinforced by Collins' arrival, King agreed to the proposal.[20]

Collins arrived at the Derwent River on 16 February 1804, aboard Ocean, immediately taking command from the young Lieutenant by virtue of rank (Collins was a colonel). The settlement that Bowen had established at Risdon Cove was vulnerable to changing tides and poor water supply and did not impress Collins. After three trips across the Derwent River to view possible alternatives, he decided to relocate the settlement 5 miles (8.0 km) down river, on the opposite shore. They landed at Sullivans Cove on 21 February 1804, and created the settlement that was to become Hobart, making it the second-oldest-established colony in Australia.[20]

In October 1804, Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson was dispatched from Port Jackson by Governor King to establish a second colony on the northern shore of the island. He arrived at the mouth of the Tamar River, and established a camp near the current location of George Town. However, feeling exposed to the off-shore weather, a few weeks later Paterson moved his camp 50.7 km (30.5 mi) inland to found Launceston.[21]

In January 1807, Lieutenant Thomas Laycock carried dispatches on horseback from Launceston to Hobart Town overland, taking eight days to traverse the island, and he became the first European to make that journey through the interior. His southward journey followed a more westerly route, and he found the mountainous terrain hard going; however his return journey ran through the flatter midlands, and the modern main Midland Highway still follows a similar route to that first Hobart to Launceston ride.[21]

Penal colony

Although Hobart Town had initially been established to prevent the French from establishing a colony there, its isolation soon proved to be a useful attribute for a secondary penal colony.

The convicts who arrived with Bowen's expedition had been dispatched to assist with necessary labour in the establishment of the colony. However, it was soon decided that the growing population of convicts in Sydney could be better managed by breaking them up into smaller groups. Some were sent to Norfolk Island, and others to Hobart Town. Early in 1804 whilst the settlers were still camped at Risdon Cove, a strike occurred amongst the soldiers who were guarding the convicts, as they were too few to be effective in controlling the increased convict population. An agreement was made that the ratio of soldiers to convicts would be increased, and they returned to duties. Whilst some convicts were kept in gaol within Hobart Town, secondary sites such as Sarah Island and Port Arthur were later created to spread the convict labour to more isolated regions, and for the purpose of stricter confinement for repeat offenders.[22]

By 1817, an increasing number of female convicts were arriving in Hobart town, and there was not enough room to keep them in the first Hobart Town gaol. Permission was granted in 1821 by NSW Governor Lachlan Macquarie for the construction of a separate gaol for female convicts. Despite this, construction took nearly eight years, and it wasn't until December 1828 that the first female convicts began to be transferred to the Cascades Female Factory, in the foothills of Mount Wellington.[23]

The “female factories” in Tasmania constituted a system of female convict prisons located in four locations across Van Diemen’s Land, in Hobart, George Town, Launceston and Ross. The latter factories were constructed in the early 1830s to alleviate overcrowding issues within the Cascades Female Factory.[24] Eleanor Casella argues that the design of the female factories were predicated on the thought that convict women could be morally reformed through the prescription of manual labour, thus these institutions were essentially turned into economically productive, government supervised “manufactories”.[25] According to Adrien Howe, the experiences of the convict women in Tasmania’s colony during the nineteenth-century were much more interlinked with the prison institutions then the male convicts, who were largely employed in the construction of infrastructure within the colony.[26] Textile manufacturing was chosen as the primary program to implement within the female factories as, besides being a traditionally gendered industry, it was the most practical to fit within the factory-like atmosphere of the prison.[27] The factory played a multiplicity of roles within Hobart’s society; it functioned as source of labour, a marriage bureau, gaol and hospital.[28] After women had served their sentences, or after periods of nominal good behaviour, they were promoted to a “hiring class” which meant that they were ready to be employed within domestic service, often on farmland, within the hospital or a role within the prison itself.[29] The factory administration was responsible for integrating the female convicts back into society.[30] Today, the Cascades Female Factory remains as a historic site for tourists to explore the heritage of Hobart’s female convict landscape. By 1851, there was a sum of approximately 12,000 convict women that had been transported to the Van Diemen’s Land colony.[31] Casella maintains that contrary to traditional portrayals of these women as “a monolithic bunch of damned whores,” most of them were convicted of petty crime, serving sentences of seven to fourteen years.[32]

The opening of penal settlements at Maria Island (1825) and Port Arthur (1832) on the Tasman Peninsula, 111 km Southeast of Hobart Town, brought more importance to the island's East Coast, which resulted in the closing of Sarah Island penitentiary in 1833. The first land grants at Richmond were made in 1823, however the township began to grow much more rapidly after Port Arthur was founded, as it soon became an important stop on the highway to Port Arthur. Richmond Gaol was soon opened in 1825, and the oldest surviving bridge in Australia, the Richmond Bridge, was built there across the Coal River in 1823. The penitentiary at Port Arthur, although now remembered as a cruel and unpleasant place, was at the time one of the most advanced prisons. Improvements were made with the opening in 1853 of the 'separate prison', also known as the "model prison", the design of which was based on the modernised prison of Pentonville in London. Conditions were fair, a legitimate attempt was made to reform men, and boys were taught a trade and given religious lessons in a very pious society. Port Arthur was guarded by day and night by a line of soldiers and dogs, across the isthmus of the peninsula.[33]

In 1831 the need for better facilities to contain the convicts within Hobart Town was answered by the opening of the Campbell Street Gaol with its magnificent Penitentiary Chapel, and open execution yard. Law Courts were soon added, and remained in use until 1983. The gaol features underground passages and solitary confinement cells.[34] Port Arthur the site of the secondary punishment penitentiary opened in 1830. By 1835 it had grown to house 800 convicts, many of whom regularly served in chain gangs. It operated until 1877.

Only 6% of convicts in Hobart were kept confined in gaols. The majority were used on government building projects, such as the Sorell Causeway, or worked as indentured servants for free settlers. Despite this relative freedom, some continued to offend and transgressors were often confined by heavy leg irons, and flogged for minor indiscretions.[35]

Convict transportation to Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) was to last exactly 50 years. In the 1840s, a strong local opposition group grew in Hobart Town known as the Anti-Transportation League, and they began lobbying the government to call for an end to convict transportation. By 1853 transportation to Van Diemen's Land was abolished, but many of the convicts already there still had lengthy sentences to complete. The success of the Anti-Transportation League led to locals calling for responsible self-government for the colony of Van Diemen's Land, which was granted in 1856, with Hobart Town remaining as the colonial capital.

Early 19th century

The first decade of the settlement on the Derwent River was a difficult one. Its geographic isolation, even from the other Australian settlement at Sydney, soon became apparent, and led to an air of despondency. The settlers initially struggled to come to terms with the environment of the new location, finding the summers hot and unbearable, and the winters nearly as cold as England.

The settlement was plagued with problems such as a shoddy workforce (mostly unskilled convict labour, and unwilling Marines pressed into work duties), insufficient supplies and neglect by imperial authorities, disease and constant threat of Aboriginal attack, difficult terrain, and quarrels amongst settlers. There were also insufficient tools, and timber-cutting was slow going in the thick forests, making it difficult to supply timber for permanent buildings. At times disaster hovered, but never became absolute.[36]

Lieutenant Bowen's settlement at Risdon Cove had been poorly sited. He had chosen it based on the advice of an earlier expedition, that had found the creek at Risdon swollen with fresh water. Bowen's contingent had arrived on 11 September 1803 at the end of what was probably a wet winter. The grassy woodlands around Risdon Cove were verdant and lush, and the creek was at full flow. However, after a long hot summer between December 1803 and February 1804, during which the Risdon Cove encampment received not a single day of rain whatsoever, the creek was dried up completely and the grass and woodlands parched.[37]

Tidal fluctuations at the mouth of the narrow inlet upon which the camp was located made launching vessels difficult for much of the day, and the camp had a poor water supply. In addition, the site was hilly and the soil was sandy and unsuitable for European agricultural practices. To make matters worse, as the creek dried into the summer months, swarms of mosquitoes and flies plagued the camp. As the summer lengthened, wildfire became more frequent, and on one occasion, the officers' huts were nearly consumed.[21]

The soldiers were virtually mutinous by the time Captain David Collins arrived on 16 February 1804. Fed up with poor rations, forced labour, and surly convicts to guard, the men had all but lost any respect for Lieutenant Bowen. Bowen immediately felt threatened by the arrival of Collins, and for a time refused to accept his command. Eventually Bowen departed aboard Ocean to seek confirmation from Governor King.[36]

.jpg.webp)

Soon after his arrival, Collins decided to move the settlement to the far shore of the river. Surveyor George Harris was dispatched in a longboat, and within a day had reported back to Collins that he had located an excellent sheltered cove at the mouth of a fast flowing stream that seemed fed by the melted snow off Table Mountain (now Mount Wellington). He suggested the location would provide ample drinking water, whilst the cove would protect the ships from the current and weather. Most of the tents were struck two days later, and re-erected at Sullivans Cove on Monday, 20 February 1804. The following Sunday, 26 February 1804 the colony's chaplain, the Right Reverend Robert Knopwood, conducted the first divine service in Hobart Town.[21]

Before the settlement at Risdon Cove had been completely abandoned, one of the most violent conflicts of the Australian frontier wars occurred. The facts of this event are still disputed by historians and the descendants of the Tasmanian Aborigines, however, on the morning of 3 May 1804, a food hunting party of approximately three hundred crested the heavily wooded hills above the Risdon Cove settlement, looking for kangaroo, in what is now considered to be part of the Oyster Bay tribe's traditional hunting grounds. Both the Marine sentries, and the hunting party surprised each other. It is not clear how the engagement began, with differing accounts being given. It does seem that, feeling threatened by such an overwhelmingly large group, the Marines fired upon the Aborigines. A convict by the name of Edward White claimed to have seen this. Armed with only spears and clubs, the Aboriginals were outdone by the firepower of the Marines who were armed with the Brown Bess smooth bore, muzzle loading muskets, many of whom were experienced troops from conflicts in India and the Americas. It is claimed that between three and fifty of the Aboriginals were killed.[38]

This was just the first incident in what would become a complete breakdown in relations between European settlers and the indigenous population in Van Diemen's Land. A series of bloody encounters between the two groups continued for much of the next twenty years, culminating in the Black War. Between the warfare and the effects of diseases brought by the settlers, the Aboriginal population was soon forced away from the area and rapidly replaced by free settlers and the convict population.[39]

Within the first two days of having landed at Sullivans Cove, shelter was provided for all of the Europeans through the erection of tents. With the winter approaching, the establishment of permanent shelters was of top priority, but took much longer than desired. The difficulty in obtaining timber from the thick forests, and establishing clearings on which to build, proved worse than first believed. A lack of saws, axes and other cutting tools made this process even harder. A shortage of building materials beset the colony, and local manufacture of timber products was slower than had been hoped.[39]

A wharf out of Hunter Island was built by the fourth day to facilitate the unloading of supplies from the ships. A crude storehouse was also established on the island, which could be accessed via a low sandbar at high tide. The long spit could only be traversed at low tide, making it easier for sentries to guard the storehouse from would-be thieves.[39]

By July, the settlement at Risdon Cove had been abandoned, and many of Bowen's initial party, with the exception of the few free settlers, returned to Sydney. By the time of Bowen's eventual departure, few permanent houses had been built, and the winter of 1804 was a particularly wet one, making conditions in the new settlement very unpleasant. Most suffered from the cold and wet, and disease soon broke out.[40]

The colony of Hobart Town initially struggled to survive. Expected supply ships did not arrive in the first year, and the lack of cultivation of wheat that was essential for survival, combined with bad droughts and soaring temperatures in the summers of 1805 and 1806 nearly ended the colony. All of the settlers, soldiers and convicts were put onto short rations when the supply ships failed to arrive.[41]

By early 1806, bay whaling had begun in the mouth of the Derwent River but by October 1806, the signs for the coming summer were bad. Chaplain to Lieutenant-Governor Collins, Reverend Robert Knopwood wrote in his diary late in October:

The distress of the colony is beyond conception.

In November:

The weather is very dry. Nothing grows for want of rain…the grubs destroy all our vegetables.

By Christmas Day, the temperature was so high he wrote of the heat:

that it bent the glass of the thermometer and broke it.

Supplies from Sydney were interrupted in 1806 after flooding on the Hawkesbury River destroyed farms and crops. At the same time, the wheat crop on the Derwent failed due to drought. To overcome food shortages, the settlers turned to fishing, and even gathering seaweed to eat. They managed to survive through the prudent use of the farm animals that had been sent by early supply ships, which included cattle, sheep, goats, horses, pigs and poultry. In fact, the settlers were better supplied with animals than equipment.[36]

As the area surrounding the river was explored, areas such as the Coal River Valley were discovered to be suitable for agriculture, and were soon producing substantial harvests. Unlike Sydney, where harsh summer conditions made the first attempts at agriculture difficult, Hobart Town's crops in 1806 and 1807 were so successful there was a large surplus of wheat and produce.[39]

Although both exploration and settlement were hampered by the island's mountainous topography, the colony soon established itself, and local food production replaced a dependency on external supply, and settlers began to better exploit the area's natural resources. The climate, similar to England's, was found to be suitable for fruit orchards, particularly apples and pears, and the raising of livestock soon also began. The best resource of southern Van Diemen's Land though, was the sea. The River Derwent possesses one of the finest deep-water natural harbours in the world, and abundant marine life provided plentiful food supplies. Whaling and sealing soon cropped up as important industries, and provided the economic backbone of Hobart Town in its first decade.[13]

The first overland journey through the island's interior was made in February 1807. Lieutenant Thomas Laycock led a party of five soldiers from the New South Wales Corps overland from the island's second settlement at Port Dalrymple (later Launceston) in the north to Hobart Town in the south seeking supplies for the struggling northern colony, as they were running low on food. His party took nine days on foot, via a central route of approximately 180 km (110 mi) high into the lakes district of the Central Highlands. Their unexpected arrival in Hobart Town out of the bush to the north of the colony elicited a rousing reception in the town. Hobart Town brought cartloads of supplies despite the southern colony also suffering shortages, and their return journey found a less arduous route north following the flatter midlands route further to the east of the southward journey, which formed the route that the Midland Highway follows today, and was completed without having to cut down a single tree to allow the carts to pass. Surveyor Charles Grimes was sent out the following month to formally survey the route, and a road between the two settlements was established by 1808.[42]

Despite this initial expedition, exploration and road building into the interior was slow. Eventually the route would be later developed as the principal north–south road in the island, but it took several years to do so. As a result, the colony of Hobart Town used sea routes, even to the north of the island, as the primary means of transportation. By 1808, docks that survive to this day were constructed using convict labour, and vital buildings such as the government store were erected. The Commissariat's Store, which was completed in 1810, survives to the present, and is Hobart's oldest surviving building. The Bond Store, completed over a decade later in 1824, also still survives.[43]

Although the first arrivals were almost entirely made up of convicts and soldiers, it was not long before rumours of Van Diemen's Land began to attract free settlers, allowing Hobart Town to grow. But Hobart Town's isolation also led to a large number of 'undesirables' seeking to escape from former crimes, escaping the law, or just looking for a life of solitude finding their way to the fledgling town. The area around the docks was rife with crime and prostitution, and heavy drinking and fighting were common.[44]

The 1810s saw Hobart Town grow from a pioneer encampment into a town. Governor Lachlan Macquarie toured the Hobart Town settlement in 1811, not long after his appointment in New South Wales, and his suppression of the Rum Rebellion, whilst he was still brimming with energy and confidence. He was interested in the island, Hobart Town especially, but was disappointed at the poor state of defence, and general disorganisation that the colony had been left in at the time of Collin's death. Although some important infrastructure had been built, the town itself was still essentially a disorganised collection of crude wattle and daub huts that Macquarie described as "untidy". By this stage, the first Government House, only six years old, was already falling to pieces.[45]

Macquarie laid out plans for the widening of existing streets, and planned for further roads, laying them out in a typically ordered fashion. He divided Hobart Town into a principal square, and seven streets to be named Macquarie, Elizabeth, Argyle, Liverpool, Murray, Harrington, and Collins, and framed a regular plan of the town. Buildings were to be properly built, or repaired, and there was to be a new church and courthouse. He located major civic institutions, such as a hospital, barracks, new market, and a system of signal stations, which have left his imprint upon modern Hobart, and much of his planned works can still be seem today. In 1811, he planned for the settlement in Northern Van Diemen's Land to be administered from Hobart Town, instead of a separate sub-colony responsibility to Sydney. This was effective by June 1812, and upon his arrive in 1813, Thomas Davey became the first Lieutenant-Governor of both North and South Van Diemen's Land.[46]

Along with planning for a new grid of streets to be laid out, and new administrative and other buildings to be built, he ordered the construction of the Bond Store, which was completed in 1815, and commissioned the building of Anglesea Barracks, which opened in 1814, and is now the oldest continually occupied barracks in Australia. The Anglesea Barracks continued to be expanded with addition of a Hospital in 1818, a Drill Hall in 1824, a new Guard House in 1838, and new Military Gaol in 1846, all of which survive to the present. By 1818, the Mulgrave Battery had been built on Castray Esplanade, on the southern side of Battery Point upon the orders of Lieutenant-Governor William Sorell. Now Hobart Town had two basic fortifications.[47]

By 1814, several farms were already located outside the settlement proper. They were mostly centred upon land grants that the imperial government used to reward hard-working free settlers, or convicts who had served their sentences. In the first four years of the Hobart Town settlement (up to 1808), a total of only 2,453 acres (9.93 km2) had been granted, mostly north, west and south of the Settlement. These grants were made in the areas that make up the modern Hobart Suburbs of Battery Point (Mulgrave Point), Sandy Bay (Queenborough), Dynnyrne, South Hobart, West Hobart, North Hobart, and New Town.[48]

No official grants were made in 1811, and 1812, due to the Rum Rebellion in Sydney. Despite this hiatus, by 1814 the area of land grants had reached 43,077.5 acres (174.328 km2), with a whopping 33,544.5 made in 356 grants in 1813 alone, Thomas Davey's first year as Lieutenant-Governor. The grants Davey issued were mostly in the districts of Clarence Plains east of the Derwent River), and in the Derwent Valley to the north of the settlement, but also included areas around Launceston. This new group of citizens with personal land-holdings formed the basis of the newly established local society of landed gentry, despite many of them having had no previous upper-class background.[48]

By 1820, Hobart Town had grown to accommodate over 10,000 people, and had become an important Pacific base for the Royal Navy. The plentiful natural resources of the island also proved useful for the Royal Navy, who had soon turned Hobart into a thriving port. The docks were busy as the Navy shipped materials such as timber, flax and rum from Hobart Town. By this time it had become a vital re-supply stop for international shipping and trade, and therefore a major freight hub for the British Empire. Wealth poured into the port on the back of this trade, and in 1823 the Van Diemen's Land Bank, the first in the colony, began operations.[47]

In the twenty years immediately after settlement, Hobart Town became a base for the South Seas whaling and sealing industries. Hobart Town's shipyards built many of the whalers, and were kept busy with maintenance and repairs. Whale oil soon became a major export, and was used to light the street lamps of London, and the wool industry had also established itself as a major export from Hobart Town's docks. In 1816, there were 20,000 sheep, and by 1818, 12,000 horned cattle. Merino and other flocks were established in the now expanding Midlands district, and at Clarendon, Perth, Longford, Esk Vale, Jericho, Simmonds and elsewhere. Soon merino stud rams were being sold for high prices, and Van Diemen's Land became noted throughout the empire for its fine wool. Wheat crops were produced in such abundance that it was being exported to Sydney to subsidise their less successful crops. The Van Diemen's Land Company was formed in 1825 to raise sheep in the colony to provide wool for British cloth manufacturers who were then buying wool from Spain and Germany, as sheep bred in Britain were largely meat breeds.[49]

The Van Diemen's Land Company was very unpopular in Hobart Town. The settlers felt that it would use all the convict labour, and be favoured by government. The company started out trying to grow wheat and barley but found the crops often ruined by heavy rain. Arthur also gave the company no favours, and it fell into financial trouble in the 1850s. The company was, however, successful in growing potatoes, finding the island's climate and soil well suited to that and oats, peas, wheat, and grass for hay to feed livestock.[47]

Education and religion were becoming increasingly important at this time, as a way to break class barriers through education and religious devotion. In 1828, there were eight government primary schools. By 1835 that number had increased to 29, with the number continuing to increase steadily over the next few years. Secondary education would remain in private hands well into the late 19th century. Libraries came early to Hobart Town, with a reading and Newspaper room established in 1822, and the Hobart Town Book Society opened in 1826, although the Tasmanian Public Library (now the State Library of Tasmania) did not open until 1870.[50]

Mid-19th century

1830 saw the consolidation of land settlement throughout the island. The most fertile parts of the island were now occupied by land holdings. Until 1831, the governor had extensive power for granting land, along with the disposition of convict labour. After 1831, free grants were abolished and all land was then sold by auction. This attracted the new class of "gentry farmers", who were more successful than earlier farmers, as the gentry farmers knew more about farming, and had more money to pay for tools and labour. Many of them became successful sheep farmers, and capitalised on the Australian wool booms on the 1820s and 30's.[50]

Although the first decade focussed on gaining a foothold on the island, and the second concerned with the establishment of essential primary industries, very soon industrial development began to branch out. It had been discovered that the Tasmanian climate was exceptionally suited to the growing of fruit. The Hobart Town Almanack in 1833 described the growth of apples and plums as "astonishing", and apple orchards were planted in the Huon Valley in the 1840s. Many of the original orchards continue operating to this day. Hops for beer were first grown in the northern settlement in 1804, and at Hobart Town in 1806. Robert Clarke was granted land at Clarence Plains in 1806 for growing hops, and became the first brewer of beer in the colony.[51]

Many small-scale breweries had soon sprung up. No large scale operations began until in 1824, when Charles Degreaves established the Cascade Brewery near the Cascade Falls in the foothills of Mount Wellington. By 1832, the brewery outgrew its original building. Degreaves relocated the brewery to the site of an old sawmill, slightly further upstream along the Hobart Rivulet, and a further three storeys were added to the main building in 1927, creating the iconic structure that survives to this day. The Brewery is still in operation and remains Australia's longest continually operating brewery.[52]

This was a particularly important time for whaling and its associated industries of shipbuilding and cooperage in Hobart Town as well. The waterfront of Hobart was upgraded in the 1830s to account for ever-increasing numbers of visiting foreign ships. Although the dock areas remained quite rough and ready, other areas of Hobart Town were developing into quite pleasant locales. In the early 1820s the shoreline of the river immediately to the north of the town had been set aside as the Kings Domain (later Queen's Domain) for use as a public space.

Van Diemen's Land had been proclaimed a separate colony from New South Wales in 1824; it had been decided by 1825 that Hobart Town would be the new colony's capital city. An executive council (effectively a cabinet of chief public servants) and a legislative council (consisting of free citizens chosen by the government and lesser public servants) as well as a local judiciary in the form of the Supreme Court of Tasmania were established in Hobart Town, with the Supreme Court Building being erected in 1824. Governor Arthur continued control as before, however.[53]

Governor Arthur drew up plans for a Botanical Gardens on the domain, which were opened in 1828, and for the creation of a grand new Government House nearby that was opened in 1858. Later that year, a convict built brick wall was added which featured internal fireplaces that heated the wall in order to allow exotic tropical plants to grow along its length. A second such wall, 280 metres in length was later added, and is now the longest surviving convict built wall in Australia.[6]

By 1830, the population of Hobart Town was around 6,000.[54] However, Hobart Town had grown to become a quaint, picturesque and thriving southern ocean port town. The whaling, sealing, wool and wattle oil industries were booming, as were agricultural crops such as wheat and apple growing. The economy was thriving, and life was quite comfortable for the merchants and free residents of the colony's capital.[6]

Some of the early settlers to Hobart Town, who had arrived with very little, had become very wealthy members of Hobart Town's new gentry class, often with vast tracts of land, especially in the Midlands. One such example is Henry Hopkins. Hopkins arrived in Hobart Town in 1822 with a shipment of boots when they were in short supply. He made a huge profit and invested the earnings in local wool for export to England. He had begun life in Hobart Town sharing a two-room house with an earth floor with his wife. However, after ten years of exporting wool, he was wealthy enough to build "Westella House", then the biggest in Hobart Town, and still standing today. It had 48 rooms and the dining room could seat 60 guests.[55]

Hopkins was influential in the early history of Van Diemen's Land. He became a community leader and magistrate soon after arriving. He campaigned heavily to abolish transportation, which had already been abolished in New South Wales. This placed a heavier burden on Van Diemen's Land, which by 1830 was Britain's only external gaol. He was one of the founders of congregationalism in Hobart Town and built a chapel at his own expense in Collins Street. He also contributed to building funds for the still existent St. David's Anglican Cathedral, as well as other Presbyterian and Wesleyan churches, and started scholarships for theological students.[55]

Although Hobart Town was becoming more commercially successful, the number of felons transported from England to the colony had dramatically increased by the late 1820s and 1830s. Demobilisation following the Napoleonic Wars had left thousands of veterans unemployed, and many turned to crime, resulting in an increasing number of transported felons. The Campbell Street Gaol had opened in 1831, and its magnificent penitentiary chapel, designed by John Lee Archer was added later in the same year. The chapel remains one of the finest examples of colonial Georgian architecture in Australia. Two further wings were added to the gaol in 1860 and were soon converted to Criminal Courts that remained in use until 1985.[56]

Charles Darwin visited Hobart Town arriving there on 5 February 1836 as part of the HMS Beagle expedition. He writes of Hobart Town and the Derwent estuary in his Voyage of the Beagle:

...The lower parts of the hills which skirt the bay are cleared; and the bright yellow fields of corn, and dark green ones of potatoes, appear very luxuriant... I was chiefly struck with the comparative fewness of the large houses, either built or building. Hobart Town, from the census of 1835, contained 13,826 inhabitants, and the whole of Tasmania 36,505. If I was obliged to emigrate I certainly should prefer this place: the climate & aspect of the country almost alone would determine me.

Hobart Town had become a town dependent on external trade. Although many of the primary industries were highly successful, they were never conducted on a scale sufficient to bring long lasting wealth. By the 1830s, the sealing industry had petered out, and although whaling persisted, it was on a scale diminished from the first twenty years. Despite the decline in these industries, the export of Tasmanian wool continued to thrive. New industries were required to replace the declining trades, and shipbuilding was one of the new successes for Hobart Town in the 1830s. The quality of the island's hardwood timber resources, combined with excellent port facilities and access to major shipping routes meant that by 1850, Hobart Town was producing more wooden ships than all other Australian ports combined. Hobart built ships plied all of the world's oceans, and could be found as far a-field as the United States and Europe.[57]

As often proved to be the case in Hobart's history, the world advanced faster than the city. Just as Hobart Town was growing to dominate the international shipbuilding trade, shortages of labour struck the industry, as men migrated en masse to the Victorian goldfields, and the shift towards steam and steel in shipbuilding undermined Hobart's production of quality wooden built ships.[57]

Hobart Town had developed a reputation as a rowdy town very soon after its foundation. The area immediately to the north of the docks had become a bustling waterfront district called 'Wapping', and was a mixture of crowded terrace housing, pubs, hotels, brothels, and gambling houses as well as various other forms of seedy entertainment for visiting sailors. Cockfighting and dog fighting were popular in the area. The Theatre Royal, built in 1834, is located in the area, and Wapping was very much seen as the entertainment part of the town. The theatre was fitted out with a plush Georgian interior which was restored after the fire which affected it in 1984.[57]

The wild nature of Hobart Town's seedier side almost had a disastrous effect. The town was in danger of losing trade from Royal Navy vessels due to the large number of sailors contracting venereal diseases whilst on shore leave in the port. The local authorities clamped down on the behaviour in the area, and the visits were allowed to continue.

Outside of Wapping the town was growing well. Numerous grand sandstone buildings and colonial residences were being built. Whilst Wapping remained an inner city residential slum, the wealthier residents were moving south of the town to Battery Point and Sandy Bay. In the 1810s and 20s, Battery Point had been one of the first areas cultivated for farmland and crops, but by the mid-1830s, it had become a collection of cottages and fine homes, from which the port that it overlooked was operated. The area was dominated by the battery of guns from which it took its name. In 1839, 'Kelly's Steps' were built by shipwright and adventurer Captain James Kelly to provide a short-cut from the pleasant colonial houses of Kelly Street and Arthur Circus in Battery Point, directly down to the warehouse and dockyards district of Salamanca Place.[58]

In 1835 John Lee Archer designed and oversaw the construction of the sandstone Customs House facing Sullivans Cove, with construction completed in 1840. The building would later be used as Tasmania's parliament house, but its use as the Customs House is commemorated by a pub bearing the same name (built 1844) which is now a favourite of yachtsmen after they have completed the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race.

Many fine churches were also constructed. The Scot's Church was built in Bathurst Street from 1834–36, and a small brick building within the churchyard had been used from 1834 as the first Presbyterian Church in Hobart Town. The Salamanca Place warehouses and the Theatre Royal were also constructed in this period. The Greek revival St George's Anglican Church in Battery Point was completed in 1838, and later had a grand Gothic tower, designed by James Blackburn, added in 1847. St Joseph's was built in 1840. Although many such fine churches were being built throughout the town, it took another twenty years for Hobart to get a cathedral.

Sir John Franklin arrived in Hobart Town on 5 January 1837 with his wife Lady Jane Franklin to become the 5th Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen's Land. The colony they took command of was orientated towards commerce and industry, but lacking in culture and opportunities for education. Lady Jane was passionate about improving the town and colony, as was her husband. However, their liberal views were not well received by many members of Hobart Town's civil service, and civilians who benefited from exploiting convict labour did not appreciate their humane views.

Despite this, the Franklins did much to reform Hobart Town society and the colony of Van Diemen's Land in general. Lady Jane Franklin ordered built a replica Greek temple, modelled on the Parthenon and designed by James Blackburn in the bush in Lenah Valley, which opened in 1841. Inside the temple, she housed the Lady Jane Franklin Museum, resplendent with replicas of the Elgin Marbles. The Franklins inaugurated the Royal Hobart Regatta in 1838. This event has been held annually since, and features sailing, rowing, swimming, and other water-sports events, culminating in a fireworks display. They also founded Christ College, now part of the University of Tasmania, the first tertiary education institution in the city. Lady Jane attempted to establish evening gatherings to discuss art, literature and science, but these proved unpopular with well-to-do 'Hobartians', who preferred that she host parties and dances instead.

Not to be outdone by his wife, Lieutenant-Governor Franklin opened the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery a year later in October 1843. In 1844 he also founded the Royal Society of Tasmania, the first such Royal Society outside of the United Kingdom. The enlightened governorship of the Franklins brought much social and cultural improvement to Hobart Town, and culminated in the town's incorporation as a city in 1842. The town had grown from a defensive outpost into a penal settlement, and from there, into a prosperous trading port. Free settlers were outstripping the arrival of convicts, and soon the colonists were clamouring for an end to transportation, and greater self-representation. The Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science was first published in 1840; however economic depression hit all of the Australian colonies that year, and Hobart Town suffered badly in what was to be the beginning of the first of many economic downturns.[59]

By the mid-nineteenth century, elegant sandstone public buildings had replaced the crude early mud and timber edifices of the pioneering days, and many fine stately colonial mansions were being built in the town by the colony's more successful citizens, such as Stowell and Secheron House (1831) in Battery Point; Runnymede (1836) in New Town (originally called 'Cairn Lodge', it was built for prominent Scottish born lawyer Robert Pitcairn); Narryna House (1840) in Battery Point; Bellkirk House (1863) in Hobart; Lenna House (1880) in Battery Point; and Westella House (1890) in Hobart. Although not as grand as some of the stately homes, many fine cottages from the same period still survive, such as Barton Cottage (1837), Moina Cottage (1850), Colville Cottage (1877), and Cromwell Cottage (1880). There is also whole row of magnificent sandstone houses along Macquarie Street dating from the 1850s that survive much as they originally were.[6]

The middle of the century saw Hobart Town as a major southern trading port with excellent rates of growth, well known and regularly visited, attracting commerce and emigrants. The colonial outpost prospered and had developed into an elegant city with stone buildings having replaced most of the early pioneering structures. By the mid-1840s, Hobart Town's shops were said to be as good as in many English towns, although at night the only lights in the streets were the lamps outside hotels and public houses. Some of these shop fronts can still be seen around Hobart's streets, such as the old Conner's family store in Murray Street. Hobart Town's main streets were lit by oil lamps from the 1840s, and eventually by gas lamps in 1857.[60]

Late 19th century

.JPG.webp)

Hobart Town had grown into a bustling port town by the mid 19th century. Local industries and commerce were thriving, and many local businesses began to succeed. Hobart Town's docks were struggling to cope with the demand now placed on them. The town's population was nearing 60,000 and ships were entering and departing the Derwent River on a nearly daily basis. The demand for berths and storage saw the construction of new docks and sandstone warehouses in an area which had been known as the 'Cottage Green', the former row of original cottages being demolished to make way for sandstone warehouses. By the mid-1840s, the bustling dock area had become known as the New Wharf, with access via Salamanca Place, named in honour of the Duke of Wellington's 1812 victory in the Battle of Salamanca.[58] Many of the original warehouses still survive, used as galleries, studios, cafes, bars and restaurants.[61]

Hobart's first major problems came with the combination of a general economic downturn in the 1840s, followed by the Victorian gold rush of the early 1850s. Large-scale migration to the Victorian goldfields occurred, creating a shortfall in local labour resources. As a response, the once booming economy of Hobart began to decline. Despite the economic and population declines of the early 1850s, the decade proved to be one of social and cultural advancement for the young city. Transportation of convicts to Van Diemen's Land was abolished in 1853, the last convict ship from England, the St. Vincent, arrived on 26 May 1853.[62]

Calls for responsible self-government were successful, with a new constitution drafted, and Van Diemen's Land became an independent British colony in 1856. The new colony immediately changed its name to Tasmania, to disassociate itself with its past as a penal colony.[63]

Hobart Town was proclaimed as the capital, and the Customs House at Sullivans Cove was renovated to accommodate a two house Parliament House with the previous Tasmanian Legislative Council re-constituted as the upper house, and the newly formed Tasmanian House of Assembly as the lower house. Two years later in 1858, the elegant Tudor-Gothic style Government House was completed, and by 1866 a magnificent Italian Renaissance style Town Hall had been completed adjacent to Franklin Square and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. As the colony grew, so too did the need for more administrative buildings. The Treasury Offices were built between 1859 and 1864, and a Registry of Deeds Office was built in 1884.

It was not just the administrative needs of the colony that were increasingly being catered for, but also the spiritual needs. Construction on a Catholic Cathedral designed by architect William Wardell, widely regarded as Australia's finest architect of the 19th century, was commenced in 1860, and was to be built on the site of the first Roman Catholic Church in Tasmania. In 1866, St Mary's Catholic Cathedral was opened, but without the originally designed tower. The magnificent St David's Anglican Cathedral, seat of the Bishop of Tasmania, and administrative centre of the Anglican Diocese of Tasmania, was completed in 1868 in high Gothic style, designed by George Frederick Bodley.

By the late 19th century, the central waterfront area of Wapping, which included the original wharf area built on Hunter Island, had declined dramatically as a result of government attempts to control prostitution, gambling and excessive drinking. As the areas of Wapping and to a lesser extent, Glebe declined, Battery Point and Sandy Bay located to the south of the town, were becoming home to the town's more prosperous residents. Soon, Battery Point was centred on the pleasant Arthur's Circus, where many of the cottages and fine homes of the period can still be seen. Whereas Glebe enjoyed a resurgence, the shanties and brothels of Wapping were condemned, and many were destroyed to make way for new developments, such as the wool store, that survives to this day as the Old Woolstore Hotel. Part of the area had already been reclaimed in the early 1850s for the construction of the Hobart Gas Works, which was opened amidst much fanfare on 9 March 1857, bringing gas lighting to the streets of Hobart Town for the first time.[64]

In 1870, the 48-metre (157-foot)-high shot tower was constructed by Joseph Moir at Taroona, south of Hobart, for the purpose of manufacturing shot for the Tasmanian Colonial Forces. It used gravity to drop molten lead down the inside of the tower, which formed spherical pellets and solidify when it landed in cold water at the base of the tower.

The Hobart Electric Tramway Company commenced operation in 1893, providing Hobart with the first complete electric tramway in the Southern Hemisphere. The tramway proved very popular and the route from the city to Sandy Bay Beach was always crowded in summers during the early 20th century. The tramways expanded rapidly, and suburban growth was encouraged by the lines. By the early 20th century, tramlines ran from the city depot to North Hobart, Lenah Valley, Springfield, Glenorchy, Cascade Brewery, Proctor's Road, and Sandy Bay. Single deck trams were introduced in 1906, and the Hobart City Council took over control of the company in 1912, renaming it the Hobart Metropolitan Tramways. Electric trolley buses were introduced in 1935.

An economic depression struck Hobart in the early 1890s, but some companies succeeded in spite of it. In 1891 Henry Jones established a jam factory in which he began to manufacture preserved jams and spreads using locally sourced high quality fruit produce. The factory soon came to be known simply as 'The Jam Factory' to locals, and was soon exporting jam throughout the British Empire. His company soon grew into a substantial business under the name of Henry Jones IXL, and established a second factory in Victoria.

In 1895 American writer Mark Twain visited Hobart as part of his worldwide tour of the British Empire, and wrote about his visit in his 1897 book Following the Equator. In it he writes:

How beautiful is the whole region, for form, and grouping, and opulence, and freshness of foliage, and variety of colour, and grace and shapeliness of the hills, the capes, the promontories; and then, the splendour of the sunlight, the dim, rich distances, the charm of the water-glimpses! And it was in this paradise that the yellow-liveried convicts were landed, and the Corps-bandits quartered, and the wanton slaughter of the kangaroo-chasing black innocents consummated on that autumn day in May, in the brutish old time. It was all out of keeping with the place, a sort of bringing of heaven and hell together.

Early 20th century

Hobart had been badly affected by the depression of the 1890s. The population had declined, and the economy was in recession. The early 20th century saw a shift in economic emphasis away from the traditional agricultural primary industries towards industrialisation. Henry Jones' waterfront factory had outgrown its requirements by 1911 as demand continued to grow, and Henry Jones IXL built a grand new factory on the eastern side of Constitution Dock, which was the first reinforced concrete building in Australia. In what was a pre-war period of development, several new buildings were added to the Hobart skyline in the early 20th century. In 1911, the grand new Hobart City Hall was opened, which had been designed by competition winner R. N. Butler.

A new Customs House, built in classical revival style, was opened in 1902 adjoining the original 1815 Bond Store. The iconic grand sandstone Hobart General Post office with classical clock-tower, designed by architect Alan Walker in High Victorian style, and built through funds donated by the people of Hobart in celebration of Australian Federation, opened on 2 September 1905. A telephone exchange was added in 1907. On 7 March 1912, Roald Amundsen telegraphed from the Hobart GPO that he had successfully reached the South Pole the previous December.

Although many bushfires had burned around the Hobart region since settlement, Hobart's relatively small size had meant few had caused serious damage. That changed in the summer of 1913–14, when several small bushfires burned on the slopes of Mount Wellington, and destroyed orchards, several buildings and livestock.

With the economy lagging, the Premier Walter Lee toured pre-war Germany, whose economy was booming. He was inspired by the hydroelectricity schemes of the Ruhr Valley, and realised the same method of cheap electricity production could benefit Tasmania with its mountainous interior. In 1914, the state government established the Hydro-Electric Department (later Hydro-Electric Commission) to provide cheap electricity in the hope of attracting industry to the island.

Upriver from the city key industries were established including the Pasminco Electrolytic Zinc Company, Cadbury's Chocolate Factory (1920) and the Boyer Newsprint Mills, and since the early 20th century the cheap ready supply of hydro-electric power has meant Hobart has been able to maintain a small industrial base. It has never attracted the heavy industry so desired by the state's politicians, which meant that Hobart has remained the least industrialised of all of the Australian capital cities.[6]

The Cadbury Chocolate Factory project mirrored the company's Quaker principles of taking responsibility for bettering the lives of the workers, pioneered in their Bournville operation in the United Kingdom. Architects James Earle and Bernard Walker sought to provide an all-round community, and created the Cadbury Estate alongside the factory, where the workers were provided with comfortable housing, shops, entertainment and sporting facilities, designed to engender a sense of community and personal well-being amongst Cadbury's workers.

The local economy of Hobart has continued to survive on primary industries such as agriculture and fishing, and smaller scale industries such as canneries, fruit processing works, furniture manufacture, silk and textile printing, soft drink and confectionery production. Cottage industries such as pottery, woodwork, crafts and textiles also persist.

.jpg.webp)

The first radio broadcast in Tasmania was on 17 December 1924 in Hobart. The development had come as part of a Commonwealth Government initiative earlier in 1924 to develop top quality radio broadcasting facilities in each state capital. The projects were funded by licensing fees, limiting those permitted to receive the broadcasts, but by mid-1925, 526 people in Hobart had bought licences to listen to broadcasts. The first Hobart station, 7ZL, was established by the Associated Radio Company, which was later bought by Tasmanian Broadcaster Pty Ltd in 1928. Finally, in 1932, ownership transferred to the Commonwealth Government owned Australian Broadcasting Commission as a result of an act of the Commonwealth Parliament nationalising radio companies.[65]

The transfer of ownership which brought free broadcasting to Hobart for the first time, was in time for Hobart listeners to receive news that the first Tasmanian born Prime Minister, Joseph Lyons had been appointed. 7ZL was broadcast on the 580 AM frequency with a one-kilowatt transmitter. By 1937 the Hobart audience had grown sufficiently to warrant a second station, and in that year the Post-Master General announced that 7ZR would begin transmitting on the 1160 AM frequency. The following year, Hobart listeners tuned into 7ZR to hear Don Bradman score 144 in a tour match against the Tasmanians at the TCA Ground. Since its inception, 7ZR has since remained with the ABC and now forms part of the ABC Local Radio network as ABC Radio Hobart.[65]

During the 1930s, the Modern movement of architecture became quite popular in Hobart, and although few examples survive, one such example is the Sunray Flats (1938) in Davey Street. Designed by Colin Philp of Hartley Wilson and Philp, they are an example of early International modern style architecture. The 1930s saw another building boom like that of the early 20th century, which was itself cut short by the outbreak of the Second World War

On 9 February 1934, Hobart was again visited by bad bushfires. The day was called 'Black Friday' and several homes were destroyed. Although many livestock were killed, there were no human fatalities.

On 23 January 1937, the first road to the summit of Mount Wellington was completed having taken 30 months to build, and named the 'Pinnacle Road'. It had cost £26,000 and allowed easy access from the Springs, which soon became a tourism and day-trip destination, to the Summit, which although subject to volatile weather changes, has views over Hobart and the Derwent River estuary.

Late 20th century

Although post-war Hobart was a thriving small city with a growing population and good combination of industry and primary agriculture, the city was largely confined to the western banks of the Derwent River.

The first plans for a bridge across the Derwent River had been made in 1832, but the width and depth of the river, combined with the powerful currents, proved to be too much of a deterrent for then current construction materials and techniques. A solution was hit upon to create a pontoon bridge, and in 1943, the Hobart Bridge was opened, spanning the Derwent River for the first time. To deal with the perceived problem of upriver shipping access, a lifting span was added near the western landing that allowed quite large vessels to pass through.

The Hobart Bridge had created the desired expansion of residential development on the eastern shore of the river, but by the mid-1950s, the population of the eastern shore, as it soon became commonly known, was so great that massive traffic congestion problems plagued the bridge. Stormy weather also created severe hazards on the water level roadway, with large waves sometimes sweeping over the roofs of vehicles.

By the late 1950s, it was realised a larger capacity bridge was needed. Construction on the much larger concrete arch Tasman Bridge began in May 1960, and was completed on 18 August 1964 at a total cost of £7 million. The bridge was originally four lanes, and expanded access to the eastern shore dramatically.

The 1950s brought an increased sense of mobility amongst Australians, both socially and geographically. Tourism was on the increase in Tasmania, and the state government invested £2,000,000 in the early 1950s for the construction of the 4700-ton Princess of Tasmania. Built in 1958, she was the first of a line of drive on ferries to cross the Bass Strait between Melbourne and Devonport that allowed tourists to travel by car from mainland Australia to Tasmania. Despite the popularity of the ferry service, it was already clear that aviation was the future of travel. In 1956 Lanherne Airport (now known as Hobart International Airport) was opened 20 km to the east of Hobart, and immediately created an increase in the number of tourists visiting the city.

The Hobart Metropolitan Tramways reached a peak in popularity in the 1930s and 40s, but by 1960 increased pressure from private car ownership and petrol-powered buses led to economic trouble for both passenger rail and the Hobart Tramways.

The final straw for the Tramways came on 29 April 1960 when a number 131 tram was struck by a lorry near the intersection of Elizabeth and Warwick Streets. The brakes failed as a result of the collision and the tram began to roll backwards down the steep gradient of Elizabeth Street during evening peak hour traffic. Despite being dazed by the collision, and rather than secure his own safety by jumping clear, tram conductor Raymond Donoghue guided the remaining passengers to the front of the vehicle as it was rolling backwards, and warned motorists by continuing to ring the tram's bells and desperately trying to operate the emergency hand brakes to no avail. It is estimated that the tram built up a speed of 40 to 50 miles per hour (64 to 80 km/h). The tram collided with the front of the following number 137 tram, killing Donoghue instantly. He remained vigilantly at his post throughout the disaster and in his heroism, he saved the lives of all of the passengers aboard, although 40 people were injured. Raymond Donoghue was awarded the George Cross posthumously for his actions.[66]

As a result of the accident and the economic questions, Hobart's trams were abandoned that year in favour of the Metropolitan Transport Trust's fleet of petrol driven buses. Most of the fleet of trams were sold off for scrap metal, although some were placed into storage, and the early 21st century saw calls for the restoration of a tram service, possibly as a reduced tourism service along the Hobart waterfront.

1967 proved to be a disastrous year for the city of Hobart. On 7 February 1967, a combination of high winds, a heat wave, ill-conceived back-burning and deliberate arson led to the worst outbreak of urban bushfire in Hobart's recorded history. The fires, which came to be known as 'Black Tuesday', swept down both shores of the Derwent River, driven by high winds, and destroyed countless homes and other property. 52 people were killed in the Hobart area alone, and 10 in other parts of the state. Until the disastrous Black Saturday bushfires of 2009 in Victoria, the 1967 Tasmanian bushfires represented Australia's greatest loss of life on a single day outside of wartime.

The tourism boom continued throughout the 1960s, and prompted local hotelier Greg Farrell, head of Federal Hotels group and owner of the Riviera Hotel in Lower Sandy Bay to lobby the State government to allow the construction of Australia's first legal casino.

The issue divided locals and politicians alike, and a referendum was called in 1968. With a 58% majority, the referendum was passed, and construction began on what was to become an icon of the Hobart waterfront, the 17 story dodecagonal (12-sided) tower of the Wrest Point Hotel Casino. It opened in 1973 amid much fanfare and was soon leading another tourism boom with gamblers and celebrities visiting from throughout the world.

Despite the double boom in tourism in the 1950s and 1960s, Tasmania's geographic isolation deterred the craved foreign investment in industry that was needed to stimulate the economy, and the government was constantly dealing with economic fluctuations. Hobart went through short periods of building booms, followed by longer stagnations, a cycle that continued into the 1990s.

On Sunday 5 January 1975, a disaster occurred in Hobart when the handyweight bulk ore carrier MV Lake Illawarra collided with the Tasman Bridge in what would later be referred to as the Tasman Bridge disaster. The ship crashed into pylon 19, and then bounced across to strike pylon 18, knocking both pylons down, and also causing a 127-metre section of steel and concrete roadway to collapse onto the deck of the ship. The Illawarra sank, killing seven crew, and five motorists were killed when they drove off the gap, plunging into the river below.

Whilst many ferry services were launched to try and aid commuters stranded by the disaster, others had to endure a 20 km round trip to the temporary bridge that was constructed near Risdon Cove. Although it isolated many city workers, the disaster had a positive effect in that it encouraged a boom in the establishment of local commercial services on the eastern shore in places such as Rosny Park.

The disaster prompted the development of a second major crossing of the Derwent River near the location of the temporary Bailey bridge at Risdon Cove, 10 km to the north of the Tasman Bridge. With Federal Government funding, the $49 million Bowen Bridge was opened on 23 February 1984 by newly elected Prime Minister Bob Hawke. The bridge was named after Lieutenant John Bowen who had established the first British settlement at Risdon Cove in 1803, approximately 500 metres from the eastern landing of the new bridge.

The Tasman Bridge was eventually repaired, which took over two years and cost an additional $44 million. Many additional safety features, such as navigation aids, were added, and the opportunity was taken to expand the capacity to five lanes. The fifth lane is a central reversible lane that follows am and pm peak hour crossing times.

One of the largest building projects in Hobart for many years was completed in 1987 when the unpopular waterfront Hobart Sheraton Hotel (now the Grand Chancellor) was opened. Taking over two years in its construction and built on a site in the docks area, its rooms have exceptional views of Sullivans Cove and the Derwent River, but the hotel's construction was extremely unpopular with residences and commercial businesses immediately to the north who had previously enjoyed similar views, now obscured by the hotel's construction. The hotel's builders were also criticised for not sourcing enough of the sandstone coloured bricks that were meant to complement Hobart's colonial waterfront heritage. When the bricks ran out early in construction, they had to complete the project with a pinker shade of bricks that many people disliked. The construction of the Hobart Sheraton broke Wrest Point Hotel Casino's monopoly on the 4–5 star demographic.

The 1990s was a decade of substantial change for Hobart. Although a nationwide recession brought high levels of unemployment and a lowering rate of home ownership, a profound shift in the political landscape followed on from the 1989 state government election. The conservative Liberal government of Robin Gray had sought a third term in office, but had dramatically underestimated the widespread opposition to the construction of another paper pulp mill within the state, and the growing groundswell of support for the Tasmanian Greens party. In what was the worst outbreak of bushfires in the 1990s, 6 houses and over 3,000 hectares of land in the Hobart area were destroyed by fire on 17 January 1998.