HM Prison Pentonville

HM Prison Pentonville (informally "The Ville") is an English Category B men's prison, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not in Pentonville, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury area of the London Borough of Islington, north London. In 2015 the justice secretary, Michael Gove, described Pentonville as "the most dramatic example of failure" within the prisons estate.[1][2]

.jpg.webp) Pentonville Prison entrance in 2006 | |

| Location | Barnsbury, London, N7 |

|---|---|

| Security class | Adult Male and YOI/Category B&C |

| Capacity | 1,115 |

| Population | 1,111 (as of July 2022) |

| Opened | 1842 |

| Managed by | HM Prison Services |

| Governor | Ian Blakeman |

| Website | gov |

The prison today

Pentonville is a local prison, holding Category B/C adult males remanded by local magistrates' courts and the Crown Court, and those serving short sentences or beginning longer sentences. The prison is divided into these main wings:

- A wing: Early days Centre

- J wing: Enhanced wing (Drug free)

- C wing: Remands and convicted prisoners

- D wing: Remands and convicted

- E wing: Remands and convicted (Care & Separation Unit)

- F wing: Detoxification Unit (F4 F5 Vulnerable Prisoners)

- G wing: remands and convicted (G5 enhanced only)

G wing has an education department, a library and workshops.

There are problems with drugs and weapons being thrown into the prison. Following the 2016 prison escape, Camilla Poulton of Pentonville Prison Independent Monitoring Board (IMB), said:

As we reported in the summer to the Secretary of State for Justice, HMP Pentonville will remain a soft target for contraband and other security breaches as long as its dilapidated windows are in place, notwithstanding the efforts of management and staff.[3]

From 2018/2019 new windows were placed and, outside window cages, netting was put up, after the escape from G wing, around the whole prison to stop drones and parcels being received.

Mike Rolfe, chair of the Prison Officers’ Association, said:

We've been warning for a long time that there's a severe shortage of staff, staff are under pressure. Pentonville's one of those jails that's suffered really terribly from staff shortages and, you know, people not wanting to join the job there."[3]

In 2017, it was reported that the IMB described Pentonville as squalid and inhumane. Blocked toilets and leaking sewage were found, broken facilities meant prisoners going without clean clothes, showers and hot food. Prisoners were regularly confined two to a cell 12 foot by 8 foot. The report stated, "The prison struggles to ensure the basics of decency largely due to the outsourced provider responsible for maintenance: Carillion. The contract is working neither for Pentonville nor the taxpayer". The report noted improvements, including uniformed staff using body-worn cameras and anti-drone technology. There was concern about the frequency of assaults on staff, which at that time averaged about 10 a month.[4]

History

The first modern prison in London, Millbank, opened in 1816. It had separate cells for 860 prisoners and proved satisfactory to the authorities who started building prisons to deal with the rapid increase in numbers occasioned by the ending of capital punishment for many crimes and a steady reduction in transportation.

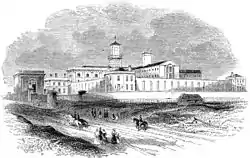

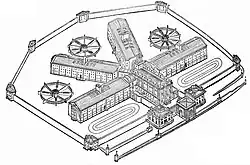

Two Acts of Parliament allowed for the building of Pentonville prison, designed by Captain Joshua Jebb, Royal Engineers, for the detention of convicts sentenced to imprisonment or awaiting transportation. Construction started on 10 April 1840 and was completed in 1842. The cost was £84,186 12s 2d.

It had a central hall with four radiating wings, all visible to staff at the centre. This design, intended to keep prisoners isolated – the "separate system" first used at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia – was not, as is often thought, a panopticon. Officers had no view into individual cells from their central position. Pentonville was designed to hold 520 prisoners under the separate system, each having his own cell, 13 feet (4 m) long, 7 feet (2 m) wide and 9 feet (3 m) high with little windows on the outside walls and opening on to narrow landings in the galleries.[6]

They were "admirably ventilated", a visitor wrote, and had a water closet, though these were replaced by communal, foul-smelling recesses because they were constantly blocked and the pipes were used for communication.[6] The cost of keeping a prisoner at Pentonville was about 15 shillings a week in the 1840s.

Prisoners were forbidden to speak to each other and when out on exercise would tramp in silent rows, wearing brown cloth masks. In chapel, which they had to attend every day, they sat in cubicles, or "coffins" as the prisoners referred to them, their heads visible to the warder but hidden from each other.[7] The chaplains were very influential, making individual cell visitations, urging the convicts to reform, and supervising the work of the schoolmasters.[8]

Mental disturbances were common. An official report admitted that "for every sixty thousand persons imprisoned in Pentonville there were 220 cases of insanity, 210 cases of delusion, and forty suicides".[7] However, conditions were better and healthier than at Newgate and similar older prisons, and each prisoner was made to do work such as picking oakum (tarred rope) and weaving. The work lasted from six in the morning until seven at night.[7] The food ration was a breakfast of 10 ounces of bread and three-quarters of a pint of cocoa; dinner was half a pint of soup (or four ounces of meat), five ounces of bread, and one pound of potatoes; supper a pint of gruel and five ounces of bread.[7]

Pentonville became the model for British prisons; a further 54 were built to similar designs over six years and hundreds throughout the British Empire. For instance, Pentonville was used as a model for the eventual construction of Corradino prison in Rahal Gdid, Malta by W. Lamb Arrowsmith in 1842.[9]

Execution site

Prisoners under sentence of death were not housed at Pentonville Prison until the closure of Newgate in 1902 when Pentonville took over executions in north London. Condemned cells were added and an execution room built to house Newgate's gallows. At the same time, Pentonville took over from Newgate the function of being the training location for future executioners.

Irish revolutionary Roger Casement was hanged there on 3 August 1916 and his remains interred at the site until 1965. Udham Singh, the Indian revolutionary, who shot and killed Sir Michael O'Dwyer (Governor of the Punjab during the Amritsar Massacre), was also held in custody and hanged at Pentonville (1940); Karl Hultén involved in the Cleft chin murder was executed 8 March 1945.

Between 1902 and 1961 a total of 120 men were executed at Pentonville [10] including Dr. Crippen and John Christie. All the executed were buried in unmarked graves, in the prison cemetery located at 51°32′44.05″N 0°06′54.62″W. The final execution took place on 6 July 1961 when Edwin Bush, aged 21, was hanged.[11]

21st century

In May 2003, an inspection report from the Chief Inspector of Prisons blamed overcrowding for poor standards at HMP Pentonville. The inspection found that basic requirements for inmates such as telephones, showers and clean clothes were not being provided regularly enough. The report also noted a lack of access to education for inmates and inadequate specialised procedures for vulnerable prisoners. The inspection report also praised a number of areas of the prison including the healthcare department, the prison drugs strategy and programmes for reducing offending behaviour.[12]

A new hospital wing, built at a cost of £15 million, was opened at Pentonville Prison in early 2005. Months later inspectors reported that despite the new facilities, primary care for prisoners such as clinical supervision of nurses and drug dispensing practices were inadequate.[13] A year later, 14 prison officers at Pentonville were suspended after allegations of trafficking and "inappropriate relations" with inmates.[14]

In August 2007, a report from the Pentonville's Independent Monitoring Board stated that the prison was infested with rats and cockroaches and had insufficient levels of staff. The report also criticised the detention conditions for mentally ill inmates, the reception facilities for new prisoners and the library provision at the jail.[15]

In October 2009, gross misconduct charges were brought against managers of Pentonville Prison after an investigation found that inmates had been temporarily transferred to HMP Wandsworth before inspections. The transfers, which included vulnerable prisoners, were in order to manipulate prison population figures.[16]

In February 2014, a report by HM Chief Inspector of Prisons Nick Hardwick said there are "huge challenges" at Pentonville and that it will not have a "viable future" without a major refurbishment and extra staff.[17]

A further report released in June 2015[18] indicated that Pentonville had "deteriorated even further" since the previous inspection. The report highlighted that many inmates were left without basic provisions, including pillows and utensils, that there were "mounds of rubbish" on the floors and cockroach infestations. Frances Cook, chief executive for the Howard League for Penal Reform, commented "when a prison is asked to hold 350 more prisoners than it is designed for, we should not be surprised when it fails".[19]

A prisoner, Jamal Mahmoud was stabbed to death on 18 October 2016 and there were six other stabbings in the following weeks up to 8 November.[20]

In 2018 monitors found Pentonville was dilapidated, overcrowded and porous to drugs, mobile phones and weapons. Windows noted as insecure in 2016 are still insecure, vermin is rife and many prisoners go for weeks without exercise in fresh air. Gang-related incidents during prayer meetings have increased. Staff are energetic and committed but there were too few staff most of the time. Wings were shut down for three or four half days a week, activities and association time were limited. At the end of July 2018 the prison held 1,215 men.[21] The IMB singled out for praise a social enterprise set up to reduce recidivism by training prisoners in cooking and entrepreneurship, Liberty Kitchen.[22]

Prisoner escapes

- 2006: Prisoner escaped during transit between Pentonville Prison and a hospital facility[23]

- 2009: Convicted arsonist Julien Chautard escaped by clinging on to the underside of the prison van which had delivered him to the jail from Snaresbrook Crown Court. He returned to the prison four days later after giving himself up to police.[24][25]

- 2012: Convicted murderer John Massey escaped from within the prison confines at Pentonville on Wednesday 27 June 2012, 18:30 BST, and was recaptured in Kent two days later following what police described as "an intelligence-led operation".[26][27]

- 2016: Two prisoners, Matthew Baker, 28, and James Whitlock, 31, escaped after they allegedly used diamond-tipped cutting equipment to break through cell bars before they scaled the perimeter wall; the escape was discovered when prison staff found pillows imitating bodies in the prisoners' beds. The public was warned not to approach the escaped prisoners.[28][29] Baker was recaptured a few days later hiding in his sister's house in Ilford, with Whitlock found by police six days after the breakout.[1][30]

The Prison Officers Association said that the escape of Baker and Whitlock followed years of underinvestment and staff cuts. Steve Gillan of the POA said, "The reality of the situation is the focus should be on Government and their budget cuts that have created this situation. The basics of security aren't getting done simply because there is not enough staff to deal with the daily tasks."[20][31] The prison's independent inspection watchdog described Pentonville as a "soft target" through the "dilapidated" state of the Victorian building. Emily Thornberry MP called the escape the "final straw" and urged that the prison should be closed. "People don't seem to be safe inside Pentonville and now it transpires inmates can escape. (...) If they don't have control of the place, what is the point of it being there? This was built in 1842 and is totally inappropriate for modern needs."[1][32]

Notable former inmates

- 1866: John Boyle O'Reilly (1844–1890), Irish activist and poet, spent 3 days in Pentonville before being transferred to Millbank.

- 1879: Charles Peace (1832–1879), notorious burglar and murderer.[33]

- 1895: Oscar Wilde spent time in Pentonville[34] before being transferred to Wandsworth.

- 1909: Madan Lal Dhingra (1883–1909), revolutionary activist with the Indian independence movement[35] who, while studying in England, assassinated British colonial officer Curzon Wyllie;[36] he was hanged at Pentonville on the 17th August,[37] denied Hindu rites and buried by the British authorities.[38] Winston Churchill privately acknowledged Dhingra's statement "[t]he Finest ever made in the name of Patriotism".[39]

- 1910: Hawley Harvey Crippen (Dr Crippen) was hanged in the prison on the 23rd November after being found guilty of murdering his wife.

- 1912: Frederick Seddon the poisoner was hanged in the prison on the 18th April.

- 1916: Roger Casement, Irish republican, was executed in the prison on the 3rd August, on charges of treason.

- 1917: Éamon de Valera, Irish republican leader and third President of Ireland.[40]

- 1940: Udham Singh, Indian independence activist responsible for the assassination of Michael O'Dwyer for which he was hanged at Pentonville Prison on the 31st July.

- 1940: Arthur Koestler was detained for six weeks after arriving in England without papers in 1940. His novel Darkness at Noon was published in England while he was still in Pentonville.

- 1946: Neville Heath was hanged in the prison on the 16th October after having been convicted of murdering one of two women (the second murder charge was not proceeded with at trial).

- 1950: Timothy Evans, wrongfully accused co-tenant of John Christie, was hanged on the 9th March.[41]

- 1953: John Christie was hanged in the prison on the 15th July after having been convicted of murdering his wife.

- 1974: Simon Dee, a radio/television personality, served 28 days for non-payment of rates on his former Chelsea home that he had not shared with his first wife since 1971/2.

- 1976: Fred Hill, political activist who protested against the compulsory wearing of crash helmets on motorcycles. Served a total of 31 prison sentences for refusing to pay fines for helmet-less riding, and died from a heart attack in Pentonville Prison in 1984.

- 1977: Robin Friday, football player with Cardiff City F.C., was arrested for impersonating a police officer at Piccadilly Circus. He spent several days in prison before being released on bail.

- 1980: Hugh Cornwell of The Stranglers served a sentence for drug possession.[42]

- 1984: Taki Theodoracopulos, gossip columnist for The Spectator, was imprisoned in Pentonville for three months in 1984 on a cocaine possession charge. He wrote a book about the experience titled Nothing to Declare.

- 1984: George Best, football player. Spent seven days imprisoned in Pentonville for driving under the influence of alcohol and assault.[43]

- 1984: Keith Allen (actor), sentenced to three months in Pentonville for destroying a bar.[44]

- 1994: David Irving, Holocaust denier and writer. Spent ten days of a three-month sentence "for contempt of court over a debt allegedly owed his German publisher".[45]

- 1999: John Alford (actor) spent six weeks in Pentonville in 1999 after selling illegal drugs to a reporter.

- 2005: Pete Doherty of The Libertines and Babyshambles spent four nights in Pentonville in February 2005 while unable to make bail on charges which were later dropped. He subsequently wrote a song about the prison, named "Pentonville", which is on the Babyshambles album Down in Albion. He spent a further six weeks in Pentonville between May and June 2011 for cocaine possession.

- 2009: Boy George, for the assault and false imprisonment of a male escort.[46]

- 2010: George Michael, for drug driving offences.[47]

- 2017: Nile Ranger (b. 1991), English footballer, for money laundering and fraud.[48]

See also

References

- McKee, Ruth (13 November 2016). "Police catch second Pentonville prison escaper". The Guardian.

- O’Connor, Mary (23 July 2015). "Islington's Pentonville prison could close under new plans". Islington Gazette. Islington Gazette. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- "Two Pentonville prisoners hid escape with 'pillow bodies'". BBC News. BBC. 7 November 2016.

- "Pentonville prison report attacks 'squalid, inhumane' conditions". the Guardian. 28 July 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- Report of the Surveyor-General of Prisons, London, 1844 reproduced in Mayhew, Henry, The Criminal Prisons of London, London, 1862.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1987). The English: A Social History, 1066-1945. Grafton Books. p. 667. ISBN 0-246-12181-5.

- Hibbert (1987), p. 668.

- Forsythe, James (1987). The Reform of Prisoners 1830-1900. Croom Helm.

- Attard, Edward (2007). Il-habs: l-istorja tal-habsijiet f'Malta (1800-2000) (in Maltese). San Ġwann, Malta: Publishers Enterprises Group (P.E.G.). p. 38.

- Pentonville prison, at Capital Punishment.org

- "Pentonville prison". Capitalpunishmentuk.org. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- "Overcrowding blamed for prison's problems". BBC News. BBC. 20 May 2003. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- "Healthcare at prison is condemned". BBC News. BBC. 4 July 2005. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- "Prison staff in 'corruption' quiz". BBC News. BBC. 14 August 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- "'Endemic squalor' at Pentonville". BBC News. BBC. 9 August 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- "Inmates 'moved before jail check'". BBC News. BBC. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- "'Drugs, filth, not enough guards': Ministers told to consider closing Pentonville prison". London Evening Standard. 18 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- "Pentonville Prison: Squalor, Violence and Cockroaches – The Implications of a Poorly Managed Prison". PrisonPhone. Prison Phone Ltd. 6 July 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "Pentonville: Overcrowded, understaffed and failing", The Howard League for penal reform, The Howard League, 23 June 2015

- "Six stabbings in Pentonville prison since death of Jamal Mahmoud". BBC. 8 November 2016.

- Pentonville prison overcrowded and drug use rife, says watchdog The Guardian

- "Stop just locking prisoners up – rehabilitate them, says IMB at HMP Pentonville". Independent Monitoring Boards. 22 August 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- Background Note on Pentonville (PDF), Howard League for Penal Reform, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016

- Henley, Jon (31 March 2009). "Great prison escapes". The Guardian. London.

- "Escaped arsonist hands himself in". BBC News. 31 March 2009.

- "Escaped murderer John Massey climbed Pentonville prison wall". BBC News. 28 June 2012.

- "Escaped murderer John Massey captured in Kent". BBC News. 29 June 2012.

- "Two escaped Pentonville prisoners left mannequins in bed". BBC News. 7 November 2016.

- "Police name Pentonville fugitives as James Whitlock and Matthew Baker". BBC News. 7 November 2016.

- "Second escaped prisoner arrested". BBC. 13 November 2016.

- Marsh, Bethan (8 November 2016). "Prison union accuses Government after two men escaped from London's HMP Pentonville". Hillingdon & Uxbridge Times.

- Rawlinson, Kevin (9 November 2016). "Pentonville prison escape: Matthew Baker caught in east London, say police". The Guardian.

- Rowland, David (1 December 2014). "Pentonville Prison". Old Police Cells Museum. The Old Police Cells Museum for Sussex Police. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Maddox, Brenda (September 2008), "Books Maketh the Man: Oscar's Books By Thomas Wright (Chatto & Windus 384pp Ł16.99)", Literary Review, archived from the original on 25 September 2008

- Chandra, Bipan (1989). India's Struggle for Independence. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-14-010781-4.

- Nehru, Jawaharlal; Nand Lal Gupta (2006). Jawaharlal Nehru on Communalism. Hope India Publications. p. 161. ISBN 978-81-7871-117-1.

- "Madan Lal Dhingra". The Open University. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Godbole, Dr Shreerang. "Madan Lal Dhingra: A lion hearted National hero". Hindu Janajagruti Samiti. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- Bandhu, Vishav (19 January 2021). The Life And Times Of Madan Lal Dhingra. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9788184302295.

- "This Week in the History of the Irish: June 15 - June 21", The Wild Geese, Luain, 14 June 2014, archived from the original on 2 April 2015

- Milmo, Cahal (6 April 2006). "Capital punishment in Britain: The hangman's story". The Independent. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Welcome to the official website of Hugh Cornwell". hughcornwell.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- O'Hagan, Sean (21 July 2002). "George Best: Been there, drunk that". The Observer – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Keith Allen: mad, bad and dangerous to know?". 4 April 2008 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "RIGHT-WING HISTORIAN FREED FROM PRISON". The Buffalo News. 23 February 1994.

David Irving... has been freed after 10 days... Irving, sentenced to three months...

- McGrath, Nick (12 October 2010). "Boy George: 'Jail's like school but you can't leave'". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- "George Michael moved to Category C Highpoint Prison". BBC News. BBC. 18 September 2010. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- "Club Statement regarding Nile Ranger". www.southendunited.co.uk.