Hill sphere

The Hill sphere of an astronomical body is the region in which it dominates the attraction of satellites. It is sometimes termed the Roche sphere. It was defined by the American astronomer George William Hill, based on the work of the French astronomer Édouard Roche.

| Part of a series on |

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

|

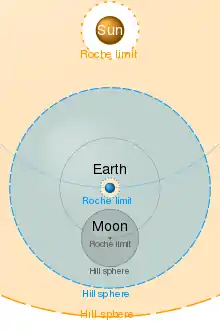

To be retained by a more gravitationally attracting astrophysical object—a planet by a more massive sun, a moon by a more massive planet—the less massive body must have an orbit that lies within the gravitational potential represented by the more massive body's Hill sphere. That moon would, in turn, have a Hill sphere of its own, and any object within that distance would tend to become a satellite of the moon, rather than of the planet itself.

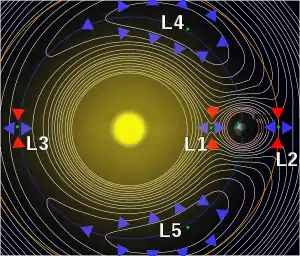

One simple view of the extent of our Solar System is that it is bounded by the Hill sphere of the Sun (engendered by the Sun's interaction with the galactic nucleus or other more massive stars).[1] A more complex example is the one at right, the Earth's Hill sphere, which extends between the Lagrange points L1 and L2, which lie along the line of centers of the Earth and the more massive Sun. The gravitational influence of the less massive body is least in that direction, and so it acts as the limiting factor for the size of the Hill sphere; beyond that distance, a third object in orbit around the Earth would spend at least part of its orbit outside the Hill sphere, and would be progressively perturbed by the tidal forces of the more massive body, the Sun, eventually ending up orbiting the latter.

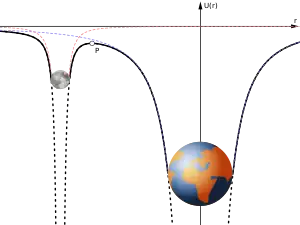

For two massive bodies with gravitational potentials and any given energy of a third object of negligible mass interacting with them, one can define a zero-velocity surface in space which cannot be passed, the contour of the Jacobi integral. When the object's energy is low, the zero-velocity surface completely surrounds the less massive body (of this restricted three-body system), which means the third object cannot escape; at higher energy, there will be one or more gaps or bottlenecks by which the third object may escape the less massive body and go into orbit around the more massive one. If the energy is at the border between these two cases, then the third object cannot escape, but the zero-velocity surface confining it touches a larger zero-velocity surface around the less massive body at one of the nearby Lagrange points, forming a cone-like point there. At the opposite side of the less massive body, the zero-velocity surface gets close to the other Lagrange point. This limiting zero-velocity surface around the less massive body is its Hill "sphere".

Definition

The Hill radius or sphere (the latter defined by the former radius) has been described as "the region around a planetary body where its own gravity (compared to that of the Sun or other nearby bodies) is the dominant force in attracting satellites," both natural and artificial.[2]

As described by de Pater and Lissauer, all bodies within a system such as the Earth's solar system "feel the gravitational force of one another", and while the motions of just two gravitationally interacting bodies—constituting a "two-body problem"—are "completely integrable ([meaning]...there exists one independent integral or constraint per degree of freedom)" and thus an exact, analytic solution, the interactions of three (or more) such bodies "cannot be deduced analytically", requiring instead solutions by numerical integration, when possible.[3]: p.26 This is the case, unless the negligible mass of one of the three bodies allows approximation of the system as a two-body problem, known formally as a "restricted three-body problem".[3]: p.26

For such two- or restricted three-body problems as its simplest examples—e.g., one more massive primary astrophysical body, mass of m1, and a less massive secondary body, mass of m2—the concept of a Hill radius or sphere is of the approximate limit to the secondary mass's "gravitational dominance",[3] a limit defined by "the extent" of its Hill sphere, which is represented mathematically as follows:[3]: p.29 [4]

- ,

where, in this representation, major axis "a" can be understood as the "instantaneous heliocentric distance" between the two masses (elsewhere abbreviated rp).[3]: p.29 [4]

More generally, if the less massive body, , orbits a more massive body (m1, e.g., as a planet orbiting around the Sun) and has a semi-major axis , and an eccentricity of , then the Hill radius or sphere, of the less massive body, calculated at the pericenter, is approximately:[5]

When eccentricity is negligible (the most favourable case for orbital stability), this expression reduces to the one presented above.

Example and derivation

In the Earth-Sun example, the Earth (5.97×1024 kg) orbits the Sun (1.99×1030 kg) at a distance of 149.6 million km, or one astronomical unit (AU). The Hill sphere for Earth thus extends out to about 1.5 million km (0.01 AU). The Moon's orbit, at a distance of 0.384 million km from Earth, is comfortably within the gravitational sphere of influence of Earth and it is therefore not at risk of being pulled into an independent orbit around the Sun. All stable satellites of the Earth (those within the Earth's Hill sphere) must have an orbital period shorter than seven months.

The earlier eccentricity-ignoring formula can be re-stated as follows:

- , or ,

where M is the sum of the interacting masses.

This expresses the relation in terms of the volume of the Hill sphere compared with the volume of the sphere defined by the less massive body's circular orbit around the more massive body, specifically, that the ratio of the volumes of these two spheres is one-third the ratio of the secondary mass to the total mass of the system.

Derivation

The expression for the Hill radius can be found by equating gravitational and centrifugal forces acting on a test particle (of mass much smaller than ) orbiting the secondary body. Assume that the distance between masses and is , and that the test particle is orbiting at a distance from the secondary. When the test particle is on the line connecting the primary and the secondary body, the force balance requires that

where is the gravitational constant and is the (Keplerian) angular velocity of the secondary about the primary (assuming that ). The above equation can also be written as

which, through a binomial expansion to leading order in , can be written as

Hence, the relation stated above

If the orbit of the secondary about the primary is elliptical, the Hill radius is maximum at the apocenter, where is largest, and minimum at the pericenter of the orbit. Therefore, for purposes of stability of test particles (for example, of small satellites), the Hill radius at the pericenter distance needs to be considered.

To leading order in , the Hill radius above also represents the distance of the Lagrangian point L1 from the secondary.

Regions of stability

The Hill sphere is only an approximation, and other forces (such as radiation pressure or the Yarkovsky effect) can eventually perturb an object out of the sphere. As stated, the satellite (third mass) should be small enough that its gravity contributes negligibly.[3]: p.26ff

Detailed numerical calculations show that orbits at or just within the Hill sphere are not stable in the long term; it appears that stable satellite orbits exist only inside 1/2 to 1/3 of the Hill radius.

The region of stability for retrograde orbits at a large distance from the primary is larger than the region for prograde orbits at a large distance from the primary. This was thought to explain the preponderance of retrograde moons around Jupiter; however, Saturn has a more even mix of retrograde/prograde moons so the reasons are more complicated.[7]

Further examples

It is possible for a Hill sphere to be so small that it is impossible to maintain an orbit around a body. For example, an astronaut could not have orbited the 104 ton Space Shuttle at an orbit 300 km above the Earth, because a 104-ton object at that altitude has a Hill sphere of only 120 cm in radius, much smaller than a Space Shuttle. A sphere of this size and mass would be denser than lead, and indeed, in low Earth orbit, a spherical body must be more dense than lead in order to fit inside its own Hill sphere, or else it will be incapable of supporting an orbit. Satellites further out in geostationary orbit, however, would only need to be more than 6% of the density of water to fit inside their own Hill sphere.

Within the Solar System, the planet with the largest Hill radius is Neptune, with 116 million km, or 0.775 au; its great distance from the Sun amply compensates for its small mass relative to Jupiter (whose own Hill radius measures 53 million km). An asteroid from the asteroid belt will have a Hill sphere that can reach 220,000 km (for 1 Ceres), diminishing rapidly with decreasing mass. The Hill sphere of 66391 Moshup, a Mercury-crossing asteroid that has a moon (named Squannit), measures 22 km in radius.[8]

A typical extrasolar "hot Jupiter", HD 209458 b,[9] has a Hill sphere radius of 593,000 km, about eight times its physical radius of approx 71,000 km. Even the smallest close-in extrasolar planet, CoRoT-7b,[10] still has a Hill sphere radius (61,000 km), six times its physical radius (approx 10,000 km). Therefore, these planets could have small moons close in, although not within their respective Roche limits.

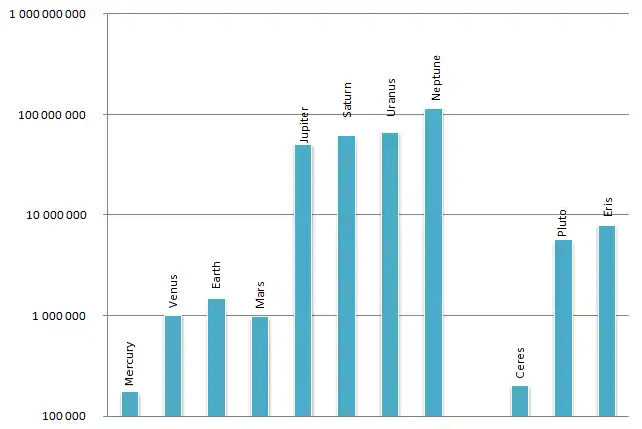

Hill spheres for the solar system

The following table and logarithmic plot show the radius of the Hill spheres of some bodies of the Solar System calculated with the first formula stated above (including orbital eccentricity), using values obtained from the JPL DE405 ephemeris and from the NASA Solar System Exploration website.[11]

| Body | Million km | au | Body radii | Arcminutes[note 2] | Furthest moon (au) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.1753 | 0.0012 | 71.9 | 10.7 | — |

| Venus | 1.0042 | 0.0067 | 165.9 | 31.8 | — |

| Earth | 1.4714 | 0.0098 | 230.7 | 33.7 | 0.00257 |

| Mars | 0.9827 | 0.0066 | 289.3 | 14.9 | 0.00016 |

| Jupiter | 50.5736 | 0.3381 | 707.4 | 223.2 | 0.1662 |

| Saturn | 61.6340 | 0.4120 | 1022.7 | 147.8 | 0.1785 |

| Uranus | 66.7831 | 0.4464 | 2613.1 | 80.0 | 0.1366 |

| Neptune | 115.0307 | 0.7689 | 4644.6 | 87.9 | 0.3360 |

| Ceres | 0.2048 | 0.0014 | 433.0 | 1.7 | — |

| Pluto | 5.9921 | 0.0401 | 5048.1 | 3.5 | 0.00043 |

| Eris | 8.1176 | 0.0543 | 6979.9 | 2.7 | 0.00025 |

See also

Explanatory notes

- Note, this is a presumption. No methodologic information about these calculations appears associated with this image creator's work or with the provenance of this image. Note as well, the exception to this assumption must be the unstated answer to the question of what was the more massive partner used in the calculations for the Sun (which cannot be answered absent a source for the image and its underlying calculations).

- At average distance, as seen from the Sun. The angular size as seen from Earth varies depending on Earth's proximity to the object.

References

- Chebotarev, G. A. (March 1965). "On the Dynamical Limits of the Solar System". Soviet Astronomy. 8: 787. Bibcode:1965SvA.....8..787C.

- Lauretta, Dante and the Staff of the Osiris-Rex Asteroid Sample Return Mission (2023). "Word of the Week: Hill Sphere". Osiris-Rex Asteroid Sample Return Mission (AsteroidMission.org). Tempe, AZ: University of Arizona. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- de Pater, Imke & Lissauer, Jack (2015). "Dynamics (The Three-Body Problem, Perturbations and Resonances)". Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26, 28–30, 34. ISBN 9781316195697. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Higuchi1, A. & Ida, S. (April 2017). "Temporary Capture of Asteroids by an Eccentric Planet". The Astronomical Journal. Washington, DC: The American Astronomical Society. 153 (4): 155. arXiv:1702.07352. Bibcode:2017AJ....153..155H. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa5daa. S2CID 119036212.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hamilton, D.P. & Burns, J.A. (March 1992). "Orbital Stability Zones About Asteroids: II. The Destabilizing Effects of Eccentric Orbits and of Solar Radiation". Icarus. New York, NY: Academic Press. 96 (1): 43–64. Bibcode:1992Icar...96...43H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90005-R.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) See also Hamilton, D.P. & Burns, J.A. (March 1991). "Orbital Stability Zones About Asteroids" (PDF). Icarus. New York, NY: Academic Press. 92 (1): 118–131. Bibcode:1991Icar...92..118H. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(91)90039-V. Retrieved 22 July 2023.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) cited therein. - Follows, Mike (4 October 2017). "Ever Decreasing Circles". NewScientist.com. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

The moon's Hill sphere has a radius of 60,000 kilometres, about one-sixth of the distance between it and Earth.

For mean distance and mass data for the bodies (for verification of the foregoing citation), see Williams, David R. (20 December 2021). "Moon Fact Sheet". NASA.gov. Greenbelt, MD: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 23 July 2023. - Astakhov, Sergey A.; Burbanks, Andrew D.; Wiggins, Stephen & Farrelly, David (2003). "Chaos-assisted capture of irregular moons". Nature. 423 (6937): 264–267. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..264A. doi:10.1038/nature01622. PMID 12748635. S2CID 16382419.

- Johnston, Robert (20 October 2019). "(66391) Moshup and Squannit". Johnston's Archive. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- "HD 209458 b". Archived from the original on 2010-01-16. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- "Planet CoRoT-7 b". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia.

- "NASA Solar System Exploration". NASA. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

Further reading

- de Pater, Imke & Lissauer, Jack (2015). "Dynamics (The Three-Body Problem, Perturbations and Resonances)". Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 28–30, 34. ISBN 9781316195697. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - de Pater, Imke & Lissauer, Jack (2015). "Planet Formation (Formation of the Giant Planets, Satellites of Planets and Minor Planets)". Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 539, 544. ISBN 9781316195697. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gurzadyan, Grigor A. (2020). "The Sphere of Attraction, the Sphere of Action and Hill's Sphere". Theory of Interplanetary Flights. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 258–263. ISBN 9781000116717. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- Gurzadyan, Grigor A. (2020). "The Roche Limit". Theory of Interplanetary Flights. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 263f. ISBN 9781000116717. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- Ida, S.; Kokubo, E. & Takeda, T. (2012). "N-Body Simulations of Moon Accretion". In Marov, Mikhail Ya. & Rickman, Hans (ed.). Collisional Processes in the Solar System. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 261. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 206, 209f. ISBN 9789401007122. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ip, W.-H. & Fernandez, J.A. (2012). "Accretional Origin of the Giant Planers and its Consequences". In Marov, Mikhail Ya. & Rickman, Hans (ed.). Collisional Processes in the Solar System. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 261. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 173f. ISBN 9789401007122. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Asher, D.J.; Bailey, M.E. & Steel (2012). "The Role of Non-Gravitational Forces in Decoupling Orbits from Jupiter". In Marov, Mikhail Ya. & Rickman, Hans (ed.). Collisional Processes in the Solar System. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 261. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 122. ISBN 9789401007122. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)