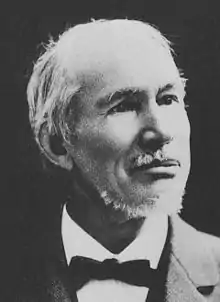

George William Hill

George William Hill (March 3, 1838 – April 16, 1914) was an American astronomer and mathematician. Working independently and largely in isolation from the wider scientific community, he made major contributions to celestial mechanics and to the theory of ordinary differential equations. The importance of his work was explicitly acknowledged by Henri Poincaré in 1905. In 1909 Hill was awarded the Royal Society's Copley Medal, "on the ground of his researches in mathematical astronomy". Today, he is chiefly remembered for the Hill differential equation.

George William Hill | |

|---|---|

George William Hill | |

| Born | March 3, 1838 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | April 16, 1914 (aged 76) West Nyack, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Rutgers University |

| Known for | |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy, mathematics |

| Institutions | Columbia University, United States Naval Observatory |

| Academic advisors | Theodore Strong |

| Signature | |

Early life and education

Hill was born in New York City to painter and engraver John William Hill and his wife, Catherine Smith. He moved to West Nyack with his family when he was eight years old. After high school, Hill attended Rutgers College, where he became interested in mathematics.

At Rutgers, Hill came under the influence of professor Theodore Strong, who was a friend of pioneering US mathematician and astronomer Nathaniel Bowditch. Strong encouraged Hill to read the great works on analysis by Sylvestre Lacroix and Adrien-Marie Legendre, as well as the treatises on mechanics and mathematical astronomy by Joseph-Louis Lagrange, Pierre-Simon Laplace, Siméon Denis Poisson, and Gustave de Pontécoulant.

Hill graduated from Rutgers College in 1859, with a Bachelor of Arts degree. In that same year he published his first scientific paper, on the geometrical curve of a drawbridge. Two years later he earned a prize from the Runkle Mathematical Monthly for his work on the mathematical theory of the figure of the Earth.

In the early 1860s, Hill began studying the works on lunar theory by Charles-Eugène Delaunay and Peter Andreas Hansen, which would inspire and motivate most of Hill's subsequent research. In 1861, Hill was hired by John Daniel Runkle to work in the United States Naval Observatory's Nautical Almanac Office, based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[1]

In 1862 Rutgers awarded Hill a Master of Arts degree. Hill lived for a while in Cambridge and later in Washington, D.C., but he preferred to carry out his mathematical work in his family farm in West Nyack, to which he retired for good after 1892.

Work on mathematical astronomy

Hill's mature work focused on the mathematics of the three-body problem,[2] and later the four-body problem, to calculate the orbits of the Moon around the Earth, as well as that of planets around the Sun. Hill was able to quantify the gravitational sphere of influence of an astronomical body in the presence of other heavy bodies, by introducing the concept of the zero-velocity surface. The space within this surface is now known as the Hill sphere and it corresponds to the region around a body within which it may capture satellites.

In 1878, Hill provided the first complete mathematical solution to the problem of the apsidal precession of the Moon's orbit around the Earth, a difficult problem in lunar theory first raised in Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica of 1687.[3] This same work also introduced what is now known in physics and mathematics as the "Hill differential equation", which describes the behavior of a parametric oscillator and which made an important contribution to the mathematical Floquet theory.

Influence and recognition

Hill's work attracted the attention of the international scientific community, and in 1894 he was chosen as president of the American Mathematical Society, serving for two years. Hill lectured at Columbia University from 1898 to 1901, but he attracted few students and he ultimately chose to return his salary and to continue working alone in his home in West Nyack, rather than within academia.[4]

Hill's Collected Works were published in 1905-07 by the Carnegie Institution for Science, with a 12-page introduction by the eminent French mathematician and theoretical physicist Henri Poincaré. In that introduction, Poincaré said that, in Hill's 1878 article titled "Researches in the lunar theory", "one is allowed to perceive the germ of most of the progress that [celestial mechanics] has made ever since".[3] Of Hill's isolation from the academic community, Poincaré declared that

This reserve, I was going to say this savagery, has been a happy circumstance for science, because it has allowed him to complete his ingenious and patient researches.[3]

George William Hill was elected as a foreign member of the Royal Society of London in 1902. He also became a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1908, and of the scientific academies of Belgium (1909), Norway (1910), Sweden (1913), and the Netherlands (1914).[5] His later years were marked by poor health, and he died in West Nyack in 1914. He never married and had no children.

Honors

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1887)

- Damoiseau Prize from the Institut de France (1898)

- Copley Medal of the Royal Society of London (1909)

- Bruce Medal of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (1909)

- Hill crater on the Moon

- Asteroid 1642 Hill

- Hill Center for the Mathematical Sciences at Rutgers University's Busch Campus

References

- Hockey, Thomas (2009). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- "Coplanar Motion of Two Planets, One Having a Zero Mass" Annals of Mathematics, Vol. III, pp. 65-73, 1887

- Gutzwiller, Martin C. (1998). "Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem". Reviews of Modern Physics. 70 (2): 589–639. Bibcode:1998RvMP...70..589G. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.70.589.

- Anton, Howard (2014). Elementary Linear Algebra. Wiley. p. 196. ISBN 978-1118434413.

- "G.W. Hill (1838 - 1914)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

Bibliography

- The collected mathematical works of George William Hill vol. 1 (Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1905–1907)

- The collected mathematical works of George William Hill vol. 2 (Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1905–1907)

- The collected mathematical works of George William Hill vol. 3, entitled A New Theory of Jupiter and Saturn, (Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1905–1907)

- The collected mathematical works of George William Hill vol. 4 (Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1905–1907)

External links

Quotations related to George William Hill at Wikiquote

Quotations related to George William Hill at Wikiquote- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "George William Hill", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir