Herbivore adaptations to plant defense

Herbivores are dependent on plants for food, and have coevolved mechanisms to obtain this food despite the evolution of a diverse arsenal of plant defenses against herbivory. Herbivore adaptations to plant defense have been likened to "offensive traits" and consist of those traits that allow for increased feeding and use of a host.[1] Plants, on the other hand, protect their resources for use in growth and reproduction, by limiting the ability of herbivores to eat them. Relationships between herbivores and their host plants often results in reciprocal evolutionary change. When a herbivore eats a plant it selects for plants that can mount a defensive response, whether the response is incorporated biochemically or physically, or induced as a counterattack. In cases where this relationship demonstrates "specificity" (the evolution of each trait is due to the other), and "reciprocity" (both traits must evolve), the species are thought to have coevolved.[2] The escape and radiation mechanisms for coevolution, presents the idea that adaptations in herbivores and their host plants, has been the driving force behind speciation.[3][4] The coevolution that occurs between plants and herbivores that ultimately results in the speciation of both can be further explained by the Red Queen hypothesis. This hypothesis states that competitive success and failure evolve back and forth through organizational learning. The act of an organism facing competition with another organism ultimately leads to an increase in the organism's performance due to selection. This increase in competitive success then forces the competing organism to increase its performance through selection as well, thus creating an "arms race" between the two species. Herbivores evolve due to plant defenses because plants must increase their competitive performance first due to herbivore competitive success.[5]

Mechanical adaptations

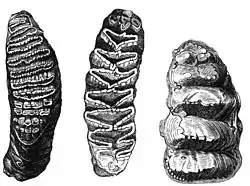

Herbivores have developed a diverse range of physical structures to facilitate the consumption of plant material. To break up intact plant tissues, mammals have developed teeth structures that reflect their feeding preferences. For instance, frugivores (animals that feed primarily on fruit) and herbivores that feed on soft foliage have low-crowned teeth specialized for grinding foliage and seeds. Grazing animals that tend to eat hard, silica-rich grasses, have high-crowned teeth, which are capable of grinding tough plant tissues and do not wear down as quickly as low-crowned teeth.[6] Birds grind plant material or crush seeds using their beaks and gizzards.

Insect herbivores have evolved a wide range of tools to facilitate feeding. Often these tools reflect an individual's feeding strategy and its preferred food type.[7] Within the family Sphingidae (sphinx moths), it has been observed that the caterpillars of species which eat relatively soft leaves are equipped with incisors for tearing and chewing, while the species that feed on mature leaves and grasses cut them with toothless snipping mandibles (the uppermost pair of jaws in insects, used for feeding).[8]

A herbivore's diet often shapes its feeding adaptations. Grasshopper head size, and thus chewing power, was demonstrated to be greater for individuals raised on rye grass (a relatively hard grass) when compared to individuals raised on red clover (a soft diet).[9] Larval Lepidoptera that feed on plants with high levels of condensed tannins (as in trees) have more alkaline midguts when compared to Lepidoptera that feed on herbs and forbs (pH of 8.67 vs. 8.29 respectively). This morphological difference can be explained by the fact that insoluble tannin-protein complexes can be broken down and absorbed as nutrients at alkaline pH levels.[10]

Biochemical adaptations

Herbivores generate enzymes that counter and reduce the effectiveness of numerous toxic secondary metabolic products produced by plants. One such enzyme group, mixed function oxidases (MFOs), detoxify harmful plant compounds by catalyzing oxidative reactions.[11] Cytochrome P450 oxidases (or P-450), a specific class of MFO, have been specifically connected to detoxification of plant secondary metabolic products. One group linked herbivore feeding on plant material protected by chemical defenses with P-450 detoxification in larval tobacco hornworms.[12] The induction of P-450 after initial nicotine ingestion allowed the larval tobacco hornworms to increase feeding on the toxic plant tissues.[12]

An important enzyme produced by herbivorous insects is protease. The protease enzyme is a protein in the gut that helps the insect digest its main source of food: plant tissue. Many types of plants produce protease inhibitors, which inactivate proteases. Protease inactivation can lead to many issues such as reduced feeding, prolonged larval development time, and weight gain. However, many insects, including S. exigua and L. decemlineatu have been selected for mechanisms to avoid the effects of protease inhibitors. Some of these mechanisms include developing protease enzymes that are unaffected by the plant protease inhibitors, gaining the ability to degrade protease inhibitors, and acquiring mutations that allow the digesting of plant tissue without its destructive effects.[13]

Herbivores may also produce salivary enzymes that reduce the degree of defense generated by a host plant. The enzyme glucose oxidase, a component of saliva for the caterpillar Helicoverpa zea, counteracts the production of induced defenses in tobacco.[14] Similarly, aphid saliva reduces its host's induced response by forming a barrier between the aphid's stylet and the plant cells.[15]

Behavioral adaptations

Herbivores can avoid plant defenses by eating plants selectively in space and time. For the winter moth, feeding on oak leaves early in the season maximized the amount of protein and nutrients available to the moth, while minimizing the amount of tannins produced by the tree.[16] Herbivores can also spatially avoid plant defenses. The piercing mouthparts of species in Hemiptera allow them to feed around areas of high toxin concentration. Several species of caterpillar feed on maple leaves by "window feeding" on pieces of leaf and avoiding the tough areas, or those with a high lignin concentration.[17] Similarly, the cotton leaf perforator selectively avoids eating the epidermis and pigment glands of their hosts, which contain defensive terpenoid aldehydes.[1] Some plants only produce toxins in small amounts, and rapidly deploy them to the area under attack. Some beetles counter this adaptation by attacking target plants in groups, thereby allowing each individual beetle to avoid ingesting too much toxin.[18] Some animals ingest large amounts of poisons in their food, but then eat clay or other minerals, which neutralize the poisons. This behavior is known as geophagy.

Plant defense may explain, in part, why herbivores employ different life history strategies. Monophagous species (animals that eat plants from a single genus) must produce specialized enzymes to detoxify their food, or develop specialized structures to deal with sequestered chemicals. Polyphagous species (animals that eat plants from many different families), on the other hand, produce more detoxifying enzymes (specifically MFO) to deal with a range of plant chemical defenses.[19] Polyphagy often develops when a herbivore's host plants are rare as a necessity to gain enough food. Monophagy is favored when there is interspecific competition for food, where specialization often increases an animals' competitive ability to use a resource.[20]

One major example of herbivorous behavioral adaptations deals with introduced insecticides and pesticides. The introduction of new herbicides and pesticides only selects for insects that can ultimately avoid or utilize these chemicals over time. Adding toxin free plants to a population of transgenic plants, or genetically modified plants that produce their own insecticides, has been shown to minimize the rate of evolution in insects feeding on crop plants. But even so, the rate of adaptation is only increasing in these insects.[21]

Microbial symbionts

Herbivores are unable to digest complex cellulose and rely on mutualistic, internal symbiotic bacteria, fungi, or protozoa to break down cellulose so it can be used by the herbivore. Microbial symbionts also allow herbivores to eat plants that would otherwise be inedible by detoxifying plant secondary metabolites. For example, fungal symbionts of cigarette beetles (Lasioderma serricorne) use certain plant allelochemicals as their source of carbon, in addition to producing detoxification enzymes (esterases) to get rid of other toxins.[22] Microbial symbionts also assist in the acquisition of plant material by weakening a host plant's defenses. Some herbivores are more successful at feeding on damaged hosts.[1] As an example, several species of bark beetle introduce blue stain fungi of the genera Ceratocystis and Ophiostoma into trees before feeding.[23] The blue stain fungi cause lesions that reduce the trees' defensive mechanisms and allow the bark beetles to feed.[24][25]

Host manipulation

Herbivores often manipulate their host plants to use them better as resources. Herbivorous insects favorably alter the microhabitat in which the herbivore feeds to counter existing plant defenses. For example, caterpillars from the families Pyralidae and Ctenuchidae roll mature leaves of the neotropical shrub Psychotria horizontalis around an expanding bud that they consume. By rolling the leaves, the insects reduce the amount of light reaching the bud by 95%, and this shading prevents leaf toughness and leaf tannin concentrations in the expanding bud, while maintaining the amount of nutritional gain of nitrogen.[26] Lepidoptera larvae also tie leaves together and feed on the inside of the leaves to decrease the effectiveness of the phototoxin hypericin in St. John's-wort.[27] Herbivores also manipulate their microhabitat by forming galls, plant structures made of plant tissue but controlled by the herbivore. Galls act as both domatia (housing), and food sources for the gall maker. The interior of a gall is composed of edible nutritious tissue. Aphid galls in narrow leaf cottonwood (Populus angustifolia) act as “physiologic sinks,” concentrating resources in the gall from the surrounding plant parts.[28] Galls may also provide the herbivore protection from predators.[29]

Some herbivores use feeding behaviors that are capable of disarming the defenses of their host plants. One such plant defensive strategy is the use of latex and resin canals that contain sticky toxins and digestibility reducers. These canal systems store fluids under pressure, and when ruptured (i.e. from herbivory) secondary metabolic products flow to the release point.[30] Herbivores can evade this defense, however, by damaging the leaf veins. This technique minimizes the outflow of latex or resin beyond the cut and allows herbivores to freely feed above the damaged section. Several strategies are employed by herbivores to relieve canal pressure, including vein cutting and trenching. Vein cutting is when a herbivore creates small openings along the length of the leaf vein, while trenching refers to the creation of a cut across the width the leaf allowing the individual to safely consume the separated portion.[31] There is also a third technique known as girdling where a folivore will create an incision going around the stem disconnecting the leaf from the canals in the rest of the plant.[31] The technique used by the herbivore corresponds to the architecture of the canal system.[32] Dussourd and Denno examined the behavior of 33 species of insect herbivores on 10 families of plants with canals and found that herbivores on plants with branching canal systems used vein cutting, while herbivores found on plants with net-like canal systems employed trenching to evade plant defenses.[32]

Herbivore use of plant chemicals

Plant chemical defenses can be used by herbivores, by storing eaten plant chemicals, and using them in defense against predators. To be effective defensive agents, the sequestered chemicals cannot be metabolized into inactive products. Using plant chemicals can be costly to herbivores because it often requires specialized handling, storage, and modification.[33] This cost can be seen when plants that use chemical defenses are compared to those plants that do not, in situations when herbivores are excluded. Several species of insects sequester and deploy plant chemicals for their own defense.[34] Caterpillar and adult monarch butterflies store cardiac glycosides from milkweed, making these organisms distasteful. After eating a monarch caterpillar or butterfly, the bird predator will usually vomit, leading the bird to avoid eating similar looking butterflies in the future.[35] Two different species of milkweed bug in the family Hemiptera, Lygaeus kalmii and large milkweed bug (Oncopeltus fasciatus), are colored with bright orange and black, and are said to be aposematically colored, in that they "advertise" their distastefulness by being brightly colored.[36]

Secondary metabolic products can also be useful to herbivores due to the antibiotic properties of the toxins, which can protect herbivores against pathogens.[37] Additionally, secondary metabolic products can act as cues to identify a plant for feeding or oviposition (egg laying) by herbivores.

References

- Karban, R., and A. A. Agrawal. 2002. Herbivore offense. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 33:641 – 664.

- Futuyma, D. J. and M. Slatkin. 1983. Introduction. Pages 1−13 in D. J. Futuyma and M. Slatkin, editors. Coevolution. Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA.

- Ehrlich, P. R. and P. H. Raven. 1964. Butterflies and plants: a study of coevolution. Evolution 18:586-608.

- Thompson, J. 1999. What we know and do not know about coevolution: insect herbivores and plants as a test case. Pages 7–30 in H. Olff, V. K. Brown, R. H. Drent, and British Ecological Society Symposium 1997 (Corporate Author), editors. Herbivores: between plants and predators. Blackwell Science, London, UK.

- Barnett, W., & Hansen, M. n.d. The Red Queen in Organizational Evolution. Strategic Management Journal. 139-157.

- Romer, A. S. 1959. The vertebrate story. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

- Bernays, E. A. 1991. Evolution of insect morphology in relation to plants. Philosophical Transactions Royal Society of London Series B. 333:257 – 264.

- Bernays, E. A., and D. H. Janzen. 1988. Saturniid and sphingid caterpillars: two mays to eat leaves. Ecology 69:1153 – 1160.

- Thompson, D. B. 1992. Consumption rates and the evolution of diet-induced plasticity in the head morphology of Melanoplus femurrubrum (Othoptera: Acrididae). Oecologia 89:204 – 213.

- Berenbaum, M. 1980. Adaptive Significance of Midgut pH in Larval Lepidoptera. The American Naturalist 115:138 – 146.

- Feyereisen, R. 1999. Insect P450 enzymes. Annual Review of Entomology 44:507 – 533.

- Snyder, M. J., and J. I. Glendinning. 1996. Causal connection between detoxification enzyme activity and consumption of a toxic plant compound. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 179:255 – 261.

- Jongsma, M. 1997. The Adaptation of Insects to Plant Protease Inhibitors. Journal of Insect Physiology. 43, 885-895.

- Musser, R. O., S. M. Hum-Musser, H. Eichenseer, M. Peiffer, G. Ervin, J. B. Murphy, and G. W. Felton. 2002. Herbivory: caterpillar saliva beats plant defense – A new weapon emerges in the evolutionary arms race between plants and herbivores. Nature 416:599 – 600.

- Felton, G. W., and H. Eichenseer. 1999. Herbivore saliva and its effect on plant defense against herbivores and pathogens. Pages 19 – 36 in A. A. Agrawal, S. Tuzun, and E. Bent, editors. Induced plant defenses against pathogens and herbivores. American Phytopathologial Society, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA.

- Feeny, P. P. 1970. Seasonal changes in oak leaf tannins and nutrients as a cause of spring feeding by winter moth caterpillars. Ecology 51:565 – 581.

- Hagen, R. H., and J. F. Chabot. 1986. Leaf anatomy of maples (Acer) and host use by Lepidoptera larvae. Oikos 47:335 – 345.

- Attenborough, David. (1900) The Trials of Life. BBC.

- Krieger, R. I., P. P. Feeny, and C. F. Wilkinson. 1971. Detoxication enzymes in the guts of caterpillars: An evolutionary answer to plant defenses? Science 172:579 – 581.

- Jaenike, J. 1990. Host specialization in phytophagous insects. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 21:243 – 273.

- Mallet, J., & Porter, P. 1992. Preventing insect adaptation to insect-resistant crops.: Are seed mixtures or refugia the best strategy? Department of Entomology. Mississippi State University. 165-169.

- Dowd, P. 1991. Symbiont-mediated detoxification in insect herbivores. Pages 411 – 440 in P. Barbosa, V. A. Krischik, and C. Jones, editors. Microbial mediation of plant – herbivore interactions. Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, USA.

- Krokene, P., and H. Solheim. 1998. Pathogenicity of four blue-stain fungi associated with aggressive and nonaggressive bark beetles. Phytopathology 88:39 – 44.

- Whitney, H. S. 1982. Relationships between bark beetles and symbiotic organisms. Pages 183 – 211 in J. B. Mitton and K. B. Sturgeon, editors. Bark beetles in North American conifers. University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas, USA.

- Nebeker, T. E., J. D. Hodges, and C. A. Blanche. 1993. Host response to bark beetle and pathogen colonization. Pages 157 – 173 in T. Schowalter, editor. Beetle-pathogen interactions in conifer forests. Academic Press, New York, USA.

- Sagers, C. L. 1992. Manipulation of host plant quality: Herbivores keep leaves in the dark. Functional Ecology 6:741 – 743.

- Sandberg, S. L., and M. R. Berenbaum. 1989. Leaf-tying by tortricid larvae as an adaptation for feeding on phototoxic Hypericum perforatum. Journal of Chemical Ecology 15:875 – 885.

- Larson, K. C., and T. G. Whitham. 1991. Mapulation of food resources by a gall-forming aphid: the physiology of sink-source interactions. Oecologia 88:15 – 21.

- Weis, A. E., and A. Kapelinski. 1994. Variable selection on Eurosta’s gall size. II. A path analysis of the ecological factors behind selection. Evolution 48:734 – 745.

- Dussourd, D. E., and R. F. Denno. 1994. Host range of generalist caterpillars: Trenching permits feeding on plants with secretory canals. Ecology 75:69 – 78.

- Dussourd, David E. (2017-01-31). "Behavioral Sabotage of Plant Defenses by Insect Folivores". Annual Review of Entomology. 62 (1): 15–34. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035030. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 27649317.

- Dussourd, D. E., and R. F. Denno. 1991. Deactivation of plant defense: correspondence between insect behavior and secretory canal architecture. Ecology 72:1383 – 1396.

- Bowers, M. D. 1992. The evolution of unpalatablility and the costs of chemical defense in insects. Pages 216 – 244 in B. D. Roitberg and M. B. Isman, editors. Insect Chemical Ecology. Chapman and Hall, New York, USA.

- Levin, D. (1976). The Chemical Defenses of Plants to Pathogens and Herbivores (Vol. 7, pp. 142-143). Annual Reviews.

- Huheey, J. E. 1984. Warning coloration and mimicry. Pages 257 – 300 in W. J. Bell and R. T. Carde, editors. Chemical Ecology of Insects. Chapman and Hall, New York, USA.

- Guilford, T. 1990. The evolution of aposematism. Pages 23 – 61 in D. L. Evans and J. O. Schmidt, editors. Insect defenses: Adaptive mechanisms and strategies of prey and predators. State University of New York Press, Albany, New York, USA.

- Frings, H., E. Goldberg, and J. C. Arentzen. 1948. Antibacterial action of the blood of the large milkweed bug. Science 108:689 – 690.

Further reading

- Rosenthal, Gerald A., & Janzen, Daniel H. (editors) (1979), Herbivores: Their Interaction with Secondary Plant Metabolites, New York: Academic Press, p. 41, ISBN 0-12-597180-X

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)