Land change modeling

Land change models (LCMs) describe, project, and explain changes in and the dynamics of land use and land-cover. LCMs are a means of understanding ways that humans change the Earth's surface in the past, present, and future.

Land change models are valuable in development policy, helping guide more appropriate decisions for resource management and the natural environment at a variety of scales ranging from a small piece of land to the entire spatial extent.[1][2] Moreover, developments within land-cover, environmental and socio-economic data (as well as within technological infrastructures) have increased opportunities for land change modeling to help support and influence decisions that affect human-environment systems,[1] as national and international attention increasingly focuses on issues of global climate change and sustainability.

Importance

Changes in land systems have consequences for climate and environmental change on every scale. Therefore, decisions and policies in relation to land systems are very important for reacting these changes and working towards a more sustainable society and planet.[3]

Land change models are significant in their ability to help guide the land systems to positive societal and environmental outcomes at a time when attention to changes across land systems is increasing.[3][4]

A plethora of science and practitioner communities have been able to advance the amount and quality of data in land change modeling in the past few decades. That has influenced the development of methods and technologies in model land change. The multitudes of land change models that have been developed are significant in their ability to address land system change and useful in various science and practitioner communities.[3]

For the science community, land change models are important in their ability to test theories and concepts of land change and its connections to human-environment relationships, as well as explore how these dynamics will change future land systems without real-world observation.[3]

Land change modeling is useful to explore spatial land systems, uses, and covers. Land change modeling can account for complexity within dynamics of land use and land cover by linking with climatic, ecological, biogeochemical, biogeophysical and socioeconomic models. Additionally, LCMs are able to produce spatially explicit outcomes according to the type and complexity within the land system dynamics within the spatial extent. Many biophysical and socioeconomic variables influence and produce a variety of outcomes in land change modeling.[3]

Model uncertainty

A notable property of all land change models is that they have some irreducible level of uncertainty in the model structure, parameter values, and/or input data. For instance, one uncertainty within land change models is a result from temporal non-stationarity that exists in land change processes, so the further into the future the model is applied, the more uncertain it is.[5][6] Another uncertainty within land change models are data and parameter uncertainties within physical principles (i.e., surface typology), which leads to uncertainties in being able to understand and predict physical processes.[5]

Furthermore, land change model design are a product of both decision-making and physical processes. Human-induced impact on the socio-economic and ecological environment is important to take into account, as it is constantly changing land cover and sometimes model uncertainty. To avoid model uncertainty and interpret model outputs more accurately, a model diagnosis is used to understand more about the connections between land change models and the actual land system of the spatial extent. The overall importance of model diagnosis with model uncertainty issues is its ability to assess how interacting processes and the landscape are represented, as well as the uncertainty within the landscape and its processes.[5]

Approaches

Machine learning and statistical models

A machine-learning approach uses land-cover data from the past to try to assess how land will change in the future, and works best with large datasets. There are multiple types of machine-learning and statistical models - a study in western Mexico from 2011 found that results from two outwardly similar models were considerably different, as one used a neural network and the other used a simple weights-of-evidence model.[7]

Cellular models

A cellular land change model uses maps of suitability for various types of land use, and compares areas that are immediately adjacent to one another to project changes into the future. Variations in the scale of cells in a cellular model can have significant impacts on model outputs.[8]

Sector-based and spatially disaggregated economic models

Economic models are built on principles of supply and demand. They use mathematical parameters in order to predict what land types will be desired and which will be discarded. These are frequently built for urban areas, such as a 2003 study of the highly dense Pearl River Delta in southern China.[9]

Agent-based models

Agent-based models try to simulate the behavior of many individuals making independent choices, and then see how those choices affect the landscape as a whole. Agent-based modeling can be complex - for instance, a 2005 study combined an agent-based model with computer-based genetic programming to explore land change in the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico.[10]

Hybrid approaches

Many models do not limit themselves to one of the approaches above - they may combine several in order to develop a fully comprehensive and accurate model.

Evaluation

Purpose

Land change models are evaluated to appraise and quantify the performance of a model’s predictive power in terms of spatial allocation and quantity of change. Evaluating a model allows the modeler to evaluate a model’s performance to edit a “model’s output, data measurement, and the mapping and modeling of data” for future applications. The purpose for model evaluation is not to develop a singular metric or method to maximize a “correct” outcome, but to develop tools to evaluate and learn from model outputs to produce better models for their specific applications [11]

Methods

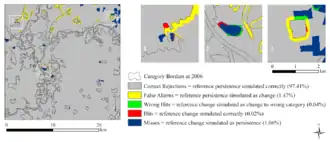

There are two types of validation in land change modeling: process validation and pattern validation. Process Validation compares the match between “the process in the model and the process operating in the real world”. Process validation is most commonly used in agent-based modeling whereby the modeler is using the behaviors and decisions to inform the process determining land change in the model. Pattern validation compares model outputs (ie. predicted change) and observed outputs (ie. reference change).[2] Three map analyses are a commonly used method for pattern validation in which three maps, a reference map at time 1, a reference map at time 2, and a simulated map of time 2, are compared. This generates a cross-comparison of the three maps where the pixels are classified as one of these five categories:

- Hits: reference change is correctly simulated as change

- Misses: reference change is simulated incorrectly as persistence

- False alarms: persistence in the reference data is simulated incorrectly as change

- Correct rejections: reference change correctly simulated as persistence

- Wrong hits: reference change simulated as correctly as change, but to the wrong gaining category[12]

Because three map comparisons include both errors and correctly simulated pixels, it results in a visual expression of both allocation and quantity errors.

Single-summary metrics are also used to evaluate LCMs. There are many single summary metrics that modelers have used to evaluate their models and are often utilized to compare models to each other. One such metric is the Figure of Merit (FoM) which uses the hit, miss, and false alarm values generated from a three-map comparison to generate a percentage value that expresses the intersection between reference and simulated change.[11] Single summary metrics can obfuscate important information, but the FoM can be useful especially when the hit, miss and false alarm values are reported as well.

Improvements

The separation of calibration from validation has been identified as a challenge that should be addressed as a modeling challenge. This is commonly caused by modelers use of information from after the first time period. This can cause a map to appear to have a level of accuracy that is much higher than a model’s actual predictive power.[13] Additional improvements that have been discussed within the field include characterizing the difference between allocation errors and quantity errors, which can be done through three map comparisons, as well as including both observed and predicted change in the analysis of land change models.[13] Single summary metrics have been overly relied on in the past, and have varying levels of usefulness when evaluating LCMs. Even the best single summary metrics often leave out important information, and reporting metrics like FoM along with the maps and values that are used to generate them can communicate necessary information that would otherwise be obfuscated.[14]

Implementation opportunities

Scientists use LCMs to build and test theories in land change modeling for a variety of human and environmental dynamics.[15] Land change modeling has a variety of implementation opportunities in many science and practice disciplines, such as in decision-making, policy, and in real-world application in public and private domains. Land change modeling is a key component of land change science, which uses LCMs to assess long-term outcomes for land cover and climate. The science disciplines use LCMs to formalize and test land change theory, and the explore and experiment with different scenarios of land change modeling. The practical disciplines use LCMs to analyze current land change trends and explore future outcomes from policies or actions in order to set appropriate guidelines, limits and principles for policy and action. Research and practitioner communities may study land change to address topics related to land-climate interactions, water quantity and quality, food and fiber production, and urbanization, infrastructure, and the built environment.[15]

Improvement and advancement

Improved land observational strategies

One improvement for land change modeling can be made through better data and integration with available data and models. Improved observational data can influence modeling quality. Finer spatial and temporal resolution data that can integrate with socioeconomic and biogeophysical data can help land change modeling couple the socioeconomic and biogeological modeling types. Land change modelers should value data at finer scales. Fine data can give a better conceptual understanding of underlying constructs of the model and capture additional dimensions of land use. It is important to maintain the temporal and spatial continuity of data from airborne-based and survey-based observation through constellations of smaller satellite coverage, image processing algorithms, and other new data to link satellite-based land use information and land management information. It is also important to have better information on land change actors and their beliefs, preferences, and behaviors to improve the predictive ability of models and evaluate the consequences of alternative policies.[2]

Aligning model choices with model goals

One important improvement for land change modeling can be made though better aligning model choices with model goals. It is important to choose the appropriate modeling approach based on the scientific and application contexts of the specific study of interest. For example, when someone needs to design a model with policy and policy actors in mind, they may choose an agent-based model. Here, structural economic or agent-based approaches are useful, but specific patterns and trends in land change as with many ecological systems may not be as useful. When one needs to grasp the early stages of problem identification, and thus needs to understand the scientific patterns and trend of land change, machine learning and cellular approaches are useful.[2]

Integrating positive and normative approaches

Land Change Modeling should also better integrate positive and normative approaches to explanation and prediction based on evidence-based accounts of land systems. It should also integrate optimization approaches to explore the outcomes that are the most beneficial and the processes that might produce those outcomes.[2]

Integrating across scales

It is important to better integrate data across scales. A models design is based on the dominant processes and data from a specific scale of application and spatial extent. Cross-scale dynamics and feedbacks between temporal and spatial scales influences the patterns and processes of the model. Process like tele-coupling, indirect land use change, and adaption to climate change at multiple scales requires better representation by cross-scale dynamics. Implementing these processes will require a better understanding of feedback mechanisms across scales.[16]

Opportunities in research infrastructure and cyberinfrastructure support

As there is continuous reinvention of modeling environments, frameworks, and platforms, land change modeling can improve from better research infrastructure support. For example, model and software infrastructure development can help avoid duplication of initiatives by land change modeling community members, co-learn about land change modeling, and integrate models to evaluate impacts of land change. Better data infrastructure can provide more data resources to support compilation, curation, and comparison of heterogeneous data sources. Better community modeling and governance can advance decision-making and modeling capabilities within a community with specific and achievable goals. Community modeling and governance would provide a step towards reaching community agreement on specific goals to move modeling and data capabilities forward.[17]

A number of modern challenges in land change modeling can potentially be addressed through contemporary advances in cyberinfrastructure such as crowd-source, “mining” for distributed data, and improving high-performance computing. Because it is important for modelers to find more data to better construct, calibrate, and validate structural models, the ability to analyze large amount of data on individual behaviors is helpful. For example, modelers can find point-of-sales data on individual purchases by consumers and internet activities that reveal social networks. However, some issues of privacy and propriety for crowdsourcing improvements have not yet been resolved.

The land change modeling community can also benefit from Global Positioning System and Internet-enabled mobile device data distribution. Combining various structural-based data-collecting methods can improve the availability of microdata and the diversity of people that see the findings and outcomes of land change modeling projects. For example, citizen-contributed data supported the implementation of Ushahidi in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake, helping at least 4,000 disaster events. Universities, non-profit agencies, and volunteers are needed to collect information on events like this to make positive outcomes and improvements in land change modeling and land change modeling applications. Tools such as mobile devices are available to make it easier for participants to participate in collecting micro-data on agents. Google Maps uses cloud-based mapping technologies with datasets that are co-produced by the public and scientists. Examples in agriculture such as coffee farmers in Avaaj Otalo showed use of mobile phones for collecting information and as an interactive voice.

Cyberinfrastructure developments may also increase the ability of land change modeling to meet computational demands of various modeling approaches given increasing data volumes and certain expected model interactions. For example, improving the development of processors, data storage, network bandwidth, and coupling land change and environmental process models at high resolution.[18]

Model evaluation

An additional way to improve land change modeling is through improvement of model evaluation approaches. Improvement in sensitivity analysis are needed to gain a better understand of the variation in model output in response to model elements like input data, model parameters, initial conditions, boundary conditions, and model structure. Improvement in pattern validation can help land change modelers make comparisons between model outputs parameterized for some historic case, like maps, and observations for that case. Improvement in uncertainty sources is needed to improve forecasting of future states that are non-stationary in processes, input variables, and boundary conditions. One can explicitly recognize stationarity assumptions and explore data for evidence in non-stationarity to better acknowledge and understand model uncertainty to improve uncertainty sources. Improvement in structural validation can help improve acknowledgement and understanding of the processes in the model and the processes operating in the real world through a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures.[2]

See also

References

- Brown, Daniel G.; et al. (2014). Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-309-28833-0.

- Brown DG, Verburg PH, Pontius Jr RG, Lange MD (October 2013). "Opportunities to improve impact, integration, and evaluation of land change models". Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 5 (5): 452–457. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.012.

- Brown, Daniel G.; et al. (2014). Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-309-28833-0.

- Briassoulis, Helen (2000). "Analysis of Land Use Change: Theoretical and Modeling Approaches". EconPapers. Archived from the original on 2017-05-15. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- Brown, Daniel G.; et al. (2014). Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-309-28833-0.

- Liu, XiaoHang; Andersson, Claes (2004-01-01). "Assessing the impact of temporal dynamics on land-use change modeling". Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. Geosimulation. 28 (1–2): 107–124. doi:10.1016/S0198-9715(02)00045-5.

- Pérez-Vega, Azucena; Mas, Jean-François; Ligmann-Zielinska, Arika (2012-03-01). "Comparing two approaches to land use/cover change modeling and their implications for the assessment of biodiversity loss in a deciduous tropical forest". Environmental Modelling & Software. 29 (1): 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2011.09.011.

- Pan, Ying; Roth, Andreas; Yu, Zhenrong; Doluschitz, Reiner (2010-08-01). "The impact of variation in scale on the behavior of a cellular automata used for land use change modeling". Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. 34 (5): 400–408. doi:10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2010.03.003.

- Seto, Karen C.; Kaufmann, Robert K. (2003-02-01). "Modeling the Drivers of Urban Land Use Change in the Pearl River Delta, China: Integrating Remote Sensing with Socioeconomic Data". Land Economics. 79 (1): 106–121. doi:10.2307/3147108. ISSN 0023-7639. JSTOR 3147108. S2CID 154022155.

- Manson, Steven M. (2005-12-01). "Agent-based modeling and genetic programming for modeling land change in the Southern Yucatán Peninsular Region of Mexico". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 111 (1–4): 47–62. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.335.6727. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2005.04.024.

- Pontius Jr R, Castella J, de Nijs T, Duan Z, Fotsing E, Goldstein N, Kasper K, Koomen E, D Lippett C, McConnell W, Mohd Sood A (2018). "Lessons and Challenges in Land Change Modeling Derived from Synthesis of Cross-Case Comparisons". In Behnisch M, Meinel G (eds.). Trends in Spatial Analysis and Modelling. Geotechnologies and the Environment. Vol. 19. Springer International Publishing. pp. 143–164. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52522-8_8. ISBN 978-3-319-52520-4.

- Varga OG, Pontius Jr RG, Singh SK, Szabó S (June 2019). "Intensity Analysis and the Figure of Merit's components for assessment of a Cellular Automata – Markov simulation model". Ecological Indicators. 101: 933–942. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.01.057. ISSN 1470-160X.

- Pontius Jr RG, Boersma W, Castella J, Clarke K, de Nijs T, Dietzel C, Duan Z, Fotsing E, Goldstein N, Kok K, Koomen E (2007-08-16). "Comparing the input, output, and validation maps for several models of land change". The Annals of Regional Science. 42 (1): 11–37. doi:10.1007/s00168-007-0138-2. ISSN 0570-1864. S2CID 30440357.

- Pontius Jr, Robert Gilmore; Si, Kangping (2014-01-06). "The total operating characteristic to measure diagnostic ability for multiple thresholds". International Journal of Geographical Information Science. 28 (3): 570–583. doi:10.1080/13658816.2013.862623. ISSN 1365-8816. S2CID 29204880.

- Brown, Daniel; et al. (2014). Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements. 500 Fifth Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001: The National Academy of Sciences. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-309-28833-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Brown, Daniel G.; et al. (2014). Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-309-28833-0.

- Brown, Daniel G; et al. (2014). Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-309-28833-0.

- Brown, Daniel G.; et al. (2014). Advancing Land Change Modeling: Opportunities and Research Requirements. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press. pp. 90–98. ISBN 978-0-309-28833-0.